LAURA VAN PROOYEN

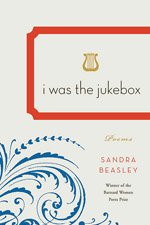

Review | I Was the Jukebox, by Sandra Beasley

|

|

“For an hour I forgot my fat self, / my neurotic innards, my addiction to alignment,” intones the piano in Sandra Beasley’s second collection, winner of the 2009 Barnard Women Poets Prize, I Was the Jukebox. So too, within this book, Beasley invites us to forget ourselves and enter a personified world that rings with the attitudes, concerns, and wishes of an unusual parade of “things.” Eschewing the personal, first-person speaker that stories her debut, Theories of Falling (New Issues/Western Michigan University Press, 2008), Beasley here lends speech to a large and varied cast of characters, ranging from a platypus and an eggplant to Osiris and Immortality. These poems are dark celebrations and criticisms driven by lyrical force and propelled by a consistently authoritative voice. Stylistically, the poems most often flex the muscle of repetition so that, reading from start to finish, the book pulses as if set to a drumbeat.

From the outset, in “The Sand Speaks,” we encounter a strong and pithy voice. In what feels like both a threat and a come-on, the sand says:

I’m fluid and omnivorous, the casual

kiss. I’ll knock up your oysters.

I’ll eat your diamonds.

Beasley, throughout the collection, often weaves colloquial phrases into the lexicon of her objects (or subjects) to disarm the reader and undercut some larger, pending danger. Here, the sand that will “knock up” the oysters beckons:

and if you’re animal small enough, come;

if you’re vegetable small enough, come;

if you’re mineral small enough, come.

The repeated phrases and, most notably, the recurring imperative lulls and seduces the reader, creating tension between the desire to “come” and knowing that to do so means the loss of self. The voice of the sand then becomes more pointed and direct as it commands: “Let’s play Hide and Go Drown. Let’s play / Pearls for His Eyes.” Repetition, combined now with clever wordplay and an allusion to The Waste Land and The Tempest, reveals the darker undercurrent of the poem; what might have felt playful or sensual has turned out to be perilous and futile. This is the beauty of so many of Beasley’s poems: they entice readers with repetition and engage our sense of rhythm and sound, only to push toward multilayered questions or insights. With the sand, as with many of the voices that inhabit this collection, we want to listen, even as we are called to examine our response to such topics as authenticity, cruelty, war, or death.

While many of the personified objects talk for themselves, several poems offer a more distanced stance, where a (presumably human) speaker’s observations comment upon historical, mythological, or theological “big ideas.” In “My God,” the speaker catalogues a series of strange and mundane attributes characterizing the divine: “My god is a short god”; “My god could levitate but prefers the stairs”; “My god / loves bacon.” The anaphoric “my god” creates dramatic urgency and generates a feeling akin to prophecy, so that a variation in syntax highlights a tonal shift: “He smiles when astronauts reach / zero gravity and say My god, My god.” Suddenly, this god is a bit full of himself, seeming to enjoy his subordinates’ proclaiming his name. The poem then briefly returns to the expected catalogue that leads to a final, somewhat sinister turn:

My god didn’t mean for icebergs. My god

didn’t mean for machetes. Sometimes

a sparrow lands in the hands of my god

and he cups it, gently. It never wants to leave

and so, it never notices that even if it tried

my god has too good a grip, my god, my god.

The speaker’s “my god, my god” echoes the astronauts’ proclamation; however, here the phrase feels more like a resigned sigh. Furthermore, the recurrence brings to mind Christ’s desperate query from the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” What began as a simple, amusing poem quickly coils its way into unanswerable questions regarding faith, entrapment, and abandonment, into the irresolvable idea of god.

Relying so heavily upon the formal device of repetition poses the risk of tedium; however, shifting the point of view within the collection helps keep the work fresh. The poems written as a direct address to an unexpected beloved, effectively capture the character’s quirky particularities. “Love Poem for College” speaks to the postadolescent years and humorously reflects upon the enthralling and often destructive experience of being a student with newfound freedom. “Love Poem for Wednesday” addresses and revels in the week’s most despondent day. The best of the “Love Poems,” written to Los Angeles, celebrates the city with all of its kitsch (“I love your red-and-white // strip joints, your car dealerships, your Bob Hope Hall / of Patriotism”) and grit (“this constant haze as if a battle just // ended”). The poem masters the complicated affair of attraction to such a complex and multifaceted entity:

though I know you dream of living forever, cancer

looks good on you. Los Angeles, I love the waysyou misunderstand me: Jew for blue, erosion for ocean.

I am rushing your Russians, I am cold for your gold.When I tell you I’m married, all you say is I do.

When I say Don’t get hurt you hear Flirt harder.

Reading I Was the Jukebox cover to cover can hypnotize you. This collection of tightly-crafted, carefully-honed work moves on its own rhythm, drawing us from poem to poem. However, the book may be best appreciated when the reader dips in to keep company with one of the many characters and examines how the richly textured verse breathes and spins. Either way, Beasley’s personifications invite us to enter a strange, funny, hopeful, and often cruel world that reaches beyond the limitations of our human selves. ![]()