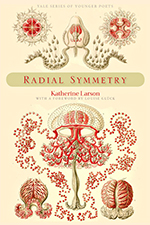

Review | Radial Symmetry, by Katherine Larson

Yale University Press, 2011

|

“I used to believe that science was only concerned / with certainty,” writes Katherine Larson in “Crypsis and Mimicry,” “Later, I recognized its mystery.” As a poet and research ecologist, Larson allows her scientific background into the poems but doesn’t attitudinize cold and objective scientific investigation as art; rather, reading the collection, we find tender poetic reckonings nuanced by science, replete with the ineffable, the unknowable, a creation that touts fact as “[a] fullness only partially fathomed.”

Radial Symmetry deserves attention not because Larson’s background fulfills some curiosity for readers but because of the profuse landscapes, sophisticated yet unidealized insights, and sultry language she renders without conceit, posture, or willful obfuscation. Above all, and we should remember, Katherine Larson is a poet writing poetry that attempts a scrupulous look at a violent and arresting world.

“My business, my art, is to live my life,” writes Michel de Montaigne in his essay “On Practice.” “[R]easoning and education cannot easily prove powerful enough to bring us actually to do anything, unless in addition we train and form our Soul by experience.” We know the consequence of Montaigne’s assiduous practice as Aristotle’s ethos: knowledge, experience, sense, credibility, wisdom. Larson writes of her education:

My entomology professor once said:

On the cephalothorax of the brown recluse

there is a pattern like a violin.

In following lines, however, she resists the trajectory of the poem and thus, perhaps, her own ethos:

Forgive me this old habit. There is a danger

in making suffering beautiful.

Is the “old habit” scientific examination? Or poetic meditation? Or rather, as the next lines hint—

This is what I realized that night in that divided city.

After playing the wretched hostel piano . . .

—it is detachment, whether scientific or aesthetic.

Once Larson establishes three entry points into the poems—the scientific, the poetic, and memory—she moves between them easily and masterfully so that where exclusion enters—“Ask the blind how carefully we build our world on light”—she counters with an image of confluence—“Ask the octopus how the evolution of our eyes converged.” In this way, she insists that a divided whole maintains a sense of wholeness, a sympathetic existence based on symmetry:

In my laboratory, immortal cancer cells

divide and divide. The pomegranatesare almost ripe. Some splintered open the way

all things fragment—into something fundamental.Either everything’s sublime or nothing is.

In the poems where a speaker says, “There are days that walk through me / and I cannot hold them” and characters “touch each other briefly / and depart. As if memory wasn’t a wound to bear,” everything is indeed sublime, even if it is painful. Her ebullient language rises always toward the ideal, the splendid. Because the sublime, however, “is to be found in a formless object,” as Kant describes in Critique of Judgment, the poems push against the boundaries of the ineffable: “Each time the intimacy becomes greater, the vocabulary less.”

Consider the scientific definition of “sublime,” the verb: to change a solid into a vapor. The ordinary sublimes into the extraordinary in Radial Symmetry. Action sublimes into memory. Experience into language. Solid into vapor. Again and again, we encounter this trope of the tangible and intangible, the knowable becoming the unknowable, a “dialectic of inside/outside.” Examples include “Statuary,” where:

somewhere . . .

between the days I pass through

and the days that pass

through me

is the mind. And memory

which outruns the body and

grief which arrests it.

and “Water Clocks”:

some histories live us. In the higher cities

of the brain,

even the speechless ones are burning.

and the long poem “Ghost Nets” that comprises the entire third section of the book. Take a look at two of its passages that pit action and abstraction against one another.

From VII:

Every day, it happens like this.

We emerge from the pale nets of sleep like ghost shrimp

in the estuaries—

The brain humming its electric language.Touching something in a state of becoming.

and from IX:

The day you sawed off the head of the dead dolphin

with your mother,

you were trying to get past the abstraction of deathto the singularity of dying.

Tension develops around the idea of formlessness and the collection’s forms. Although Larson isn’t exactly a formalist, she deftly controls the release of information with lineation and the structure of the lines. Louise Glück in the introduction writes that “Pacing is essential” in the poems and “the gravity of these unequivocal, summarizing assertions depends absolutely on the sustained images . . .” Each image exists as a kind of prism, “Quiet . . . until the sunlight”—the reader’s eye—“hits.”

For Larson, experience anchors itself in setting, the physical world. The collection moves between Arizona, the Galapagos, Tunisia, Belfast, Central America, and Leningrad. The places and the people thereof do not dissolve into symbols or allegory for the speaker’s internal concerns, however. Instead, in going about their own lives, they connect the speaker to the ineffable.

“The Oranges in Uganda” is the one exception to the realistic encounters of the collection. Larson immediately identifies the stranger in the poem:

Walking together, Death and I

are shopping for emicungwa

at night, in the market.

and then describes his appearance:

Death’s feet are bare

and covered with dirt

from the road.

He is “Cloaked in barkcloth” and “raises his ancestral spear, singing mouth full / of ulcers and steel.” If we were reading Dickinson we might expect that Death would take the speaker at the end, but the two simply “talk of small things”—

How the mosque and the half moon

stand sentinel

against the bloody sky. That mangoes

will be in season soon.

In the rest of the collection, the speakers cannot entirely connect with others, whether strangers or close companions: “I don’t pretend to imagine the lives of women tending oyster crates / in estuaries at the edge of Sonora”; “love is the mathematics // of distance”; “I cheat on everyone I love”; and “Have you ever wanted to / kiss a stranger’s hands?”. The speaker of “The Oranges in Uganda,” however, tells Death:

I know why

people make love when they

come home from a funeral. Why the pull

of the body echoes the tides,

eyes wide as graves. The way the stamens

of a passion flower spin up,

defy their stem.

At the end, Death “rises like a swallow / . . . leaving a rip no word can cover.” Because the poem is fabular and surreal, unlike the rest of the collection, how does it fit within the concerns of the other poems? Death leaves “a rip no word can cover.” Both death and language vex Larson throughout Radial Symmetry for similar reasons: neither can be quantified or dissected in the same way as a squid going under the knife. They can be observed only by their consequence, not in body.

One of the most candid passages, the end of “Love at Thirty-two Degrees,” addresses science as a lover whom she’s betrayed. The betrayal, ironically, rises from that other abstraction, love.

Science—

Beyond pheromones, hormones, aesthetics of bone,

Every time I make love for love’s sake alone,I betray you.

Throughout Radial Symmetry, Larson’s persona wrestles with the antithetical constructs of science and art, the idea that to endeavor in both betrays both. Because she cannot crush her desires to participate in either, the self feels “Split like a clam on ice, / . . . raw, half-eaten” but even as the chasm between the two deepens with her reckonings, she thrusts them together like two tectonic plates to create a quaking world that’s both challenging and unchallengable, conceived and balanced, not by “equilibrium, but buoyancy” of language and experience; after the sea’s hissing oath: “Not perfection . . . but originality.” ![]()

Katherine Larson is the author of one collection of poetry, Radial Symmetry (Yale University Press, 2011), which won the 2010 Yale Series of Younger Poets competition and the 2012 Levis Reading Prize. Larson works as a molecular biologist and field ecologist.