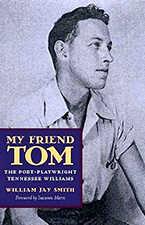

Review | My Friend Tom: The Poet-Playwright Tennessee Williams,

by William Jay Smith

Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012

|

Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie endures today as one of the most beautiful memory plays ever written. The drama focuses on four main characters. “There is a fifth character in the play who doesn’t appear except in this larger-than-life-size photograph over the mantel. This is our father who left us a long time ago.” St. Louis provides a backdrop full of both promise and pain. And through the eyes of Tom Wingfield, the drama’s narrator, we learn about his burdens, his demons, his obsessions, and his shortcomings.

William Jay Smith’s memoir My Friend Tom reveals itself as an equally beautiful memory play with an equally engrossing narrator. Even in the genre of creative nonfiction, Smith’s drama remains evident, the characters complex, and the poetic language rich and provocative. In many respects, the book seems like a meta-The Glass Menagerie. My Friend Tom’s narrator speaks of The Glass Menagerie’s narrator through personal anecdotes, shared stories, mutual experiences, and a vision of the young poet-playwright with so much detail and recognizable specifics that it proves impossible for any Tennessee Williams scholar not to draw parallels between Tom Wingfield and Tom Williams. Through Smith’s eyes, we see how Tom Williams’s eyes just might have seen the world around him.

Smith is probably best known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1968 to 1970. He is the author of such notable works as The Cherokee Lottery: A Sequence of Poems and Army Brat: A Memoir. And, fortunately for us, he also happens to have been a lifelong friend and former classmate of Tennessee Williams. Now in his nineties, Smith writes with impeccable clarity and detail. He not only has good stories to tell, but also has the good memory to draw on the experiences as well.

Though his stories are often fairly simple, their impact proves to be both complex and deep. We do not get merely a glance or a sketch of the real Tom, but somehow a full vision and thorough composite of a true three-dimensional man. Smith reveals many additional insights regarding Tom’s surprising love interests and the mysteries surrounding his death. But possibly the most intriguing detail about Tom Williams and Tom Wingfield is just how great the similarities are between these two Toms.

In page after page, Smith divulges similarities between Williams’s real life and the life of the Wingfield family. Tom and his sister, Rose Williams, attended Soldan High School in St. Louis—just as Tom and Laura Wingfield do in The Glass Menagerie. Tom and Rose enrolled in a ten-week course at Rubicam’s Business School. “Tom soon became an excellent typist, but Rose found it impossible to cope with the workload.” In The Glass Menagerie, Laura secretly abandons her studies and refuses to return to Rubicam’s because of the stress she has endured at the school. She deceptively fills her days with walks through the park or taking in a movie. Smith writes that Williams often “accompanied Rose downtown to the movies at the Loew’s State Theater,” the exact same theater Tom Wingfield mentions as his own personal refuge.

Both My Friend Tom and The Glass Menagerie highlight the significance of the father figure. Smith recounts memories of Tom’s father, Cornelius, that eerily match the father in The Glass Menagerie. Both fathers have a strong stranglehold on their sons even in absentia.

Smith mentions the importance of girls making their debuts multiple times in My Friend Tom—just as Williams mentions it multiple times in The Glass Menagerie. Smith recollects how Tom’s mother “tried to organize other social occasions to raise the tone of the family in their new home to elevate Rose’s eligibility.” Debuts were designed mostly for the upper classes to flex their social standing, and by subjecting Rose to these very functions, Edwina Williams was attempting to raise their ranks as well. Also just as Mrs. Williams placed tremendous expectations on one particular prospective husband who “seemed in every way exactly the kind of proper gentleman caller” she had unsuccessfully envisioned for Rose, her son places Amanda Wingfield in a similar scenario when she, as well as her daughter, feels jilted when Jim confesses his engagement to another girl.

“We knew something about Tom’s sister Rose, but we rarely saw her when we came to the house,” Smith remembers. This story resonates as Laura, too, wants to make herself scarce when Tom’s friend is expected for dinner. She begs her mother to allow her to stay in her bedroom while Amanda and Tom entertain the visitor. But after a brief poetic debate, Laura surrenders to her mother’s oppressiveness and attends the fateful dinner.

Many other similarities strike the reader as we discover that Edwina Williams, as well as Amanda Wingfield, disapprove of their Toms’ reading D.H. Lawrence. Both Toms get into trouble at the warehouse scribbling poems and reading great authors’ works while on the job.

Throughout the memoir, as the experiences between Smith and Williams dwindle, the specifics in the memories become less as well. Sometimes Smith writes for pages about other authors in Williams’s circle without any reference to Williams at all. At first reading these anecdotes may seem more like footnotes, but soon they reveal themselves to be intrinsic scenes in Williams’s own personal drama, which ultimately explode into a haunting and downright unsettling climax.

Smith writes of the many other writers who influenced Tennessee Williams’s literary world, so many of whom committed suicide—some in more dramatic fashion than others. Sara Teasdale took sleeping pills. Her former lover, Vachel Lindsay, swallowed Lysol. Hart Crane threw himself overboard the ship Orizaba and drowned. And Yukio Mishima committed seppuku.

Upon hearing the news of Mishima’s death in November of 1970, Williams said that Mishima “had decided that with the final novel of his tetralogy, Sea of Fertility, he had completed his life’s work as an artist and was ready to confront the ‘great mystery’ of death.”

Just seven weeks earlier, Mishima and Williams had met at a Chinese restaurant in Yokohama. They updated each other on their recent writings, and Williams admitted he was “Revising a full-length play. I call it The Two-Character Play. Probably my last one. I don’t have the energy to sustain a major work. It takes too much out of me.”

Much controversy surrounds Williams’s own death in February, 1983. Some conjecture that he choked on a bottle cap. Some claim he might have been murdered. But the New York medical examiner Dr. Michael Baden found “that Williams had swallowed enough barbiturates to cause death.” As Smith implies that Williams, too, took his own life, it seems only then in the memoir that his detailed accounts of Tennessee Williams’s friends and their suicides might have influenced Williams’s own choices.

But many other more intriguing mysteries reveal themselves in the memoir. Who knew that Williams had considered the great love of his life to be “a lovely red-haired girl” named Hazel Kramer? He even proposed to her, and, Smith writes that upon her rejection Williams was heartbroken and “thought of her for years afterward but the romance was over.” Williams confided in his mother “that the beautiful little red-head had been ‘the deepest love of his life.’” Smith recounts other stories about Tom, their friend Clark Mills, and the experiences they shared in Washington University’s Poetry Club with such specific and loving words that it brings new light to the poet-playwright’s insight and deeply paradoxical lifestyle.

In one of the oddest, yet most beautiful moments of the memoir, Smith quotes Williams’s description of a family chair in his St. Louis home:

This overstuffed chair . . . really doesn’t look like it could be removed. It seems too fat to get through a doorway. Its color was originally blue, plain blue, but time has altered the blue to something sadder than blue, as if it had absorbed in its fabric and stuffing all the sorrows and anxieties of our family life and these emotions had become its stuffing and its pigmentation (if chairs can be said to have a pigmentation) . . . It seems more like a fat, silent person, not silent by choice but simply unable to speak because if it spoke it would not get through a sentence without bursting into a self-pitying wail.

In the detailed account, Williams provides the inner character of this everyday object and personifies it in exquisite specificity. This depiction both shows us the poet at work and illustrates why Williams is often credited for creating not only beautiful dialogue, but beautiful stage directions as well.

Though My Friend Tom is a quick read, the 146-page memoir will surely influence future Williams scholarship. Through Smith’s precise, affectionate recollections, we learn not only of Williams’s beginning as a poet-playwright, but that of Smith’s as well, although Smith often shies away from his own accomplishments in order for us to fully understand Williams’s. And through these stories a remarkable friendship becomes apparent—one full of love and support, but most importantly one full of much respect and total acceptance. ![]()

William Jay Smith is the author of My Friend Tom (University Press of Mississippi, 2012). He is the author of thirteen collections of poetry and two memoirs. Smith is a professor emeritus of English at Hollins University.