Remembering Gerald Stern (1925–2022)

Gregory Donovan

|

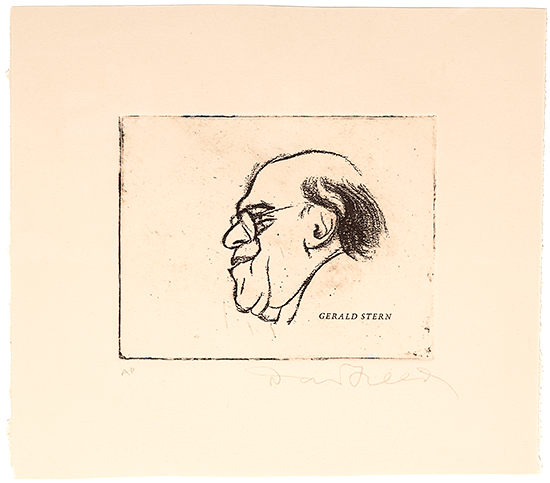

| David Freed Gerald Stern Portrait 10 in. x 8 3/4 in. etching, relief printing |

Gerald Stern wrote as he lived, with the open-hearted generosity and caring of Walt Whitman, with the brilliance and humor of a troublemaker like Lenny Bruce, and with the sharp eye, bold courage, and rebellious spirit of a union organizer—something he was in actuality as well as in attitude, since he once was the president and chief negotiator of a New Jersey teachers union. Jerry had enormous respect and regard for the working women and men he encountered, and always took time to visit with them in a personal way that went far beyond being merely polite. Jerry rarely met a stranger, only future friends. I stood beside him once as he checked into a hotel here in Richmond, and he took time to speak with the young woman behind the counter. Afterward, she turned to me and asked, “Who was that guy?” I told her he was one of America’s greatest poets. “I thought it had to be something like that,” she said.

Unlike Yeats, who felt that “The intellect of man is forced to choose / Perfection of the life, or of the work,” Stern’s poems clearly demonstrate his decision to connect the two intimately. In his inimitable style, his best-known poems show that the pressures of daily life, as well as one’s moral and political commitments, can be brought together into poems that also combine humor and tragedy, history and the now, social criticism as well as self-critique, as in “The Founder,” when he steals a “bronze head” as a sort of college prank and brings it home, so he and his friends can sledgehammer the empty head’s “shape from thoughtful oppressor / to tortured victim” and show “the close connection between the two.” But soon it all begins to feel ugly and demented, and they begin to pity the “brainless founder,” since “it wasn’t all raw Socialism and hatred / of the rich; there was a little terror in it.” So, he sells the disfigured bronze for scrap—yet, at the last moment in the poem, he’s grateful he didn’t follow his first impulse to throw it into a river, where it might have been carried along, “spinning faster and faster,” and would have become something like the head of Dionysus flowing downstream to inspire the oracle of Delphi, something now monstrous and newly dangerous with its “melodies never ending.”

That soaring move from tragicomic reality to transcendent possibility is characteristic in many of his poems, as in another of my favorites, “Morning Harvest,” which begins with several ridiculous and comical claims that “Pennsylvania spiders” are so huge they waddle like bears and hunt men and cats with their webs. But if you see those webs on “the iron bridge / going across to Riegelsville, New Jersey” in the morning light, they can magically offer you “almost one minute to study” their “drops of silver in the sun” before you have to slog back to work. But then the poem moves outward to contemplate “the children standing in the driveways” and the “mothers wrapping their quilted coats around them,” awaiting the “yellow buses flashing their lights like berserk police cars,” since it is “lights that save us” including “blue lights rushing in to help the wretched, / red lights carrying . . . oxygen down the highway” and finally, in a great leap backward and forward at once, he celebrates the human achievement of “white lights entering the old Phoenician channels / bringing language and mathematics and religion into the darkness.”

I was privileged to get to know Gerald Stern in many contexts, as a poet, a mentor of young writers, as a mensch. His warmth and kindness were matched by his intelligence, insight, and a healthy disrespect for convention and all institutional regulation. When our dear colleague Larry Levis died, his friend Gerald Stern agreed to come to Richmond to work with Larry’s bereaved grad students who felt lost and abandoned. Jerry brought healing and humor and sustenance to us all. One day during his visits, he showed up at my office door and asked me to go for a walk. No, I heard myself thinking, I’d love to, but I have so much work . . . and then I woke up. Gerald Stern is inviting me for a walk! I closed the door behind me, and we walked out of the building. He reached out his hand for mine, and there we went, walking hand in hand down the streets of Richmond, and it was grand. All along in the time he was with us, Gerald Stern was offering that hand to all of us, and even now to all of you. ![]()

Gerald Stern was the author of twenty collections of poetry, most recently Galaxy Love (W. W. Norton & Company, 2017) and Divine Nothingness (W. W. Norton & Company, 2014), and four books of essays, most recently Stealing History (Trinity University Press, 2012), a multi-genre autobiographical reflection. His poetry collection This Time: New and Selected Poems (W. W. Norton & Company, 1998) won the National Book Award. He was the recipient of other numerous awards, including the Wallace Stevens Award, the Paris Review’s Bernard F. Conners Award, the Bess Hokin Award for Poetry, the Ruth Lilly Prize, the Pennsylvania Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, and American Poetry Review’s Jerome J. Shestack Poetry Prize. He received fellowships from the Academy of American Poets, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Guggenheim Foundation, and was the Poet Laureate of New Jersey 2000–2002. He taught at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop for several years, in addition to several academic institutions: Temple University, Drew University, Pitt, Columbia, Sarah Lawrence College, New York University, Princeton, and New England College, where he cofounded their Masters of Fine Arts in Poetry.