MARY LEE ALLEN

Review | Hardscrabble, by Kevin McFadden

|

|

| The University of Georgia Press, 2008 |

One iota engaged the entire Christian Church in the fourth century in its greatest theological argument: the true nature of Christ. The Nicene Creed used the Greek word homoousia meaning “the same being” as the Father. Other creeds used the word homoiousia, “of like substance.” The row thus was over a single letter. For the Roman Empire at that time, religious dissension was a political problem, and the emperor sent into exile or prison those clerics who chose the word with the wrong number of iotas.

Kevin McFadden’s fascination with minute differences in words seems almost religious, if less punitive. Language consumes his attention. He tunnels into philosophy, the meaning of life, through what seems like wordplay. His comedic, inventive, creative ability to connect and compare sounds, spellings, and concepts makes for brilliant games with often-revealing depths. “I’m interested in how thoughts cluster around a word,” he writes. “Its real bones and its ghost limbs. . . . Approaching the word as a mandala, square within circle within square . . . .”

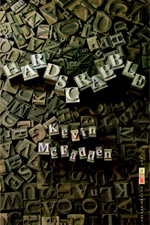

Reading Hardscrabble requires close attention to every word and every letter, beginning with the punning title. McFadden plays with every rhetorical device imaginable, especially puns and anagrams. He uses a variety of poetic forms, making up exotic new ones when his adventurous spirit inspires him. Most of the poems in the book are arranged in groups having some connecting thread: their form, their theme, or their game.

McFadden, joyfully and as earnestly as the early Christians, points out enormous differences in meanings created by altering one letter of a word. “Another Untied Shoe” has six pages arranged in a kind of antiphonal form and showing the effects of that single changed letter:

Difference slim, (a) letter thin

between the nomen and the omen

. . .

(All for naught)

and naughtiness for all

between the formal and the normal

. . .

Burning (like) an unloosed truth

between the om and the um

Off-guard in the garden

between the ample and the apple

The power of (holding)

a moment in a name

between the worm and the word

The prose-poem sequence, “It’s Tarmac,” is a stream-of-consciousness ramble the speaker records as he makes the long drive to his parents’ home:

Heading back home to Ohio. December 2000. I live in Virginia. This is not an essay, it’s a Saturn. It’s a Saturday. It’s Saturnalia—nearly—it’s nearly Christmas. . . .

Barracks Road. Gassed up, grabbed a few things. Dr. Pepper and O’Henry my company. No writing for weeks, day job taking it all out of me. Which is why I brought this recorder. Why I bought a blank tape.

From there his thoughts careen through the familiar route, keeping him awake and entertaining us. McFadden’s narrator tells about himself and his family, as well as the places he passes. He dazzles us with his knowledge of the classics, linguistics, history, especially church history—after all, he did go to a Jesuit school. “Adolph Hitler . . . said he learned a lot about terror from the Jesuits. Black uniforms, specious reasoning, unquestioning obedience, terrorism of the conscience.” He philosophizes about words and wordplay, language and his love for it. “Every credo has a coder. Cleric of the circle, I give what I have: an intense love for language and intense distrust of it.”

“Horseplay behooves me,” he claims. “Puns understandable, but not rational. They do what Newton said couldn’t be done: two bodies, same space, same time. Two or more. Intuitive etymologies: that’s what good puns intend to be.”

As a slow reader myself, I take reassurance from his observation:

Speed-reading, yes, but you don’t see slow-reading courses much. The Classicist reads slowly, and he’s the one who knows six languages. That we learn to read past individual words to get to an overarching meaning is an unfortunate setback. A lot to learn when you take a word slow. We’re velocitized.

His conciseness and his surprising discoveries of words within words make us stop and look again. We had not noticed that before. What about the philosophical import? “The anagrammarian knows flirtation is filtration. Knows danger was spelled into the garden. The runt will have his turn, the nomad his monad.”

In several long poems every line is an anagram of a short quotation. The anagrams, some more clearly than others, relate in sense to the quotation. In “Meditate Sea to Sea” the quotation played with is Langston Hughes’s “Let America be America again”:

ice-amble. A tie. Agrarian came

later, Inca came, a bare image I

bear. An Eric came, agile at aim

(let America be a maniac, I rage).

The last line reads, “Let America be America: a gain.” Another anagrammatic poem plays on Allen Ginsberg’s line, “America when will you be angelic?” McFadden’s apt end line is, “(we) be America: wily hallucinogen.”

Without mounting a soapbox, McFadden uses his art in “Names, Appalachia,” a section of the long poem “Time,” to bring our attention to strip-mining and its destruction of the landscape:

Most scenery is lost on me. Names mean

everything. You could say these mountains

blink back words like dust motes. Words

won’t bring one down, maybe water, given time.

Given time, the right word might. The right word

in the right hand, curled like a plan in a foreman’s

clenched fist, the way we have of mining

these days, not veining out at depths and at risk

but shrewdly chopping the mountains down.

Don’t be so certain the noun is dead. These days.

Don’t be sure the imperishable world

is, and the letters only stand-ins. Whatever’s called

may be called up, called out, called back. In time.

These mountains are still appellations.

When driving in foreign countries I collect names and words on signs; they amuse the unaccustomed eye or please the ear with unexpected sounds. McFadden delights in the names of small towns along the way from Virginia to Ohio. In a twenty-sonnet sequence, “Famed Cities,” he begins with “Ohio Welcomes You!,” where he makes a facetious play on place names:

Enter in Unity, exit by Empire. Begin in Youngstown,

leave by Antiquity. New Paris, Delhi, Moscow, Venice—

the infamous river ins and landish outs.

Utopia’s found on a map of Ohio, dream-keeping

a border. Alpha, yes, and yes again, Omega.

Shadyside, Lightsville, Torch and Brilliant.

I grew up near Mesopotamia, the Erie and the Ohio

were my Tigris and Euphrates.

Later, he admits “place names were always better than the places.” And away he goes with a geographical sampling of his state. Then he chooses individual towns for exploration, as in “Repetition, Rome.” He begins with towns in Ohio and ends with Tacitus:

All roads lead to Rome. And sewers, adds Lowell.

And I to that, Its plumbing led to lead.

Ohio has four Romes, a lot to own—

but one of them had the sense to start

New. What else is? Well, we finally got our

McDonald’s (you know you’re backwoods when

fast food won’t come to you) and soon that means

we can expect the rest competing for our obesity,

Kings and Queens and arches flung to the rustics.

Step by step they were led to decadent pleasures:

the lounge, the bath, the flashy banquet; these they called

in their ignorance civilization; just part of their servitude. . . .

Trickling through Tacitus, death, the first Roman

freedom: spreading in water, flowing in chains.

McFadden also plays visual games: the arrangement of words and lines on a page, not only in stanzas or paragraphs, but diagonally, or in lines broken—part on the left side of the page, part on the right—or with varying spacing between words in one line. Two of the poems in Hardscrabble, “Dread, Phalanx” and “Decimation, Tenth Legion,” look completely different from his others: Every letter is capitalized, words are irregularly broken and spaced to fill each line from margin to margin. There are no phrases, clauses, or sentences. Sense comes after repeated readings in which we set aside all customary notions of literary formality or historical sequence. Then we realize some words are related. We gain less information than feelings, impressions, auras about a subject. Without the notes at the end of the book, we might never realize that the two poems are identical except that the later poem is literally decimated, every tenth letter of the earlier poem omitted.

In Hardscrabble, McFadden’s medium is truly his message—the etymology and sounds of words. He examines, dissects, turns words inside out, breaks them into pieces, adds or subtracts small bits. He shows us not only curiosities, games, and jokes, but also hidden truths in language.

![]()