GRANT WHITE

Review | The Learners, by Chip Kidd

|

|

| Harper Perennial, 2009 |

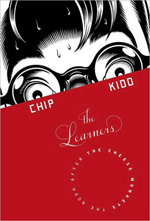

Readers familiar with Chip Kidd may feel inclined to judge his second novel, The Learners, by its cover. And Kidd, one of the world’s preeminent graphic artists, would likely condone (maybe even encourage) such a break with conventional wisdom—provided that the one doing the breaking has devoted at least a few brain cells to the job. Devotees will probably recognize the unhappy, horn-rimmed eyes of Happy, the narrator and protagonist of Kidd’s debut novel, The Cheese Monkeys (Harper Perennial, 2001). And they will likely feel a mixture of giddiness and anxiety at the prospect of a sequel. The former because of the incomparable wit and acuity Kidd demonstrates in The Cheese Monkeys. And the latter for the same reasons, plus the fear that such a feat can never be replicated. But before going any further, let’s strip off that scanty little red thing posing as a dust jacket. There. Now that the infuriating dust vest is out of the way, here is the . . . shock generator?

Well, yes. And no. The sinister device depicted on the cover of The Learners is, in fact, intended to depict the phony shock generator used by Professor Stanley Milgram in his “Behavioral Study of Obedience.” Conducted in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1961, Milgram’s study tested the willingness of its subjects to inflict harsh physical punishment, to the point of death, on relative strangers. In The Learners, Kidd employs this real-life and profoundly disturbing study as a telling counterpoint to the story’s principal focus—advertising.

As one might expect in a writer as familiar with the industry as Kidd, the narrative frame of The Learners reflects the conventions of advertising and design. The narrator, Happy, does not simply tell a story through monologue interspersed with scraps of dialogue; he is almost constantly engaging the reader in other ways, including direct address. By way of introduction, he articulates the reader’s (or in the language of advertising, the consumer’s) question, “Who am I?” and quickly responds, “I am Happy.” Of course, in this instance, he is quick to clarify that “[Happy] will always be who—not what—I am,” just in case the cynicism in his tone does not register when he tells the reader, a few paragraphs later, “Wait. I’m forgetting something. Oh. I do not write poetry.”

The loose, fragment-rich style of narration characteristic of Kidd’s two novels would be untenable if it were not for his descriptive powers. Consider Happy’s impression of Dick Stankey:

A bag of Krinkles forever grafted onto one of his mitts, he devoted himself to enjoying his company’s product in full view of humanity and did so with unashamed abandon . . . . Unfortunately, he also chewed tobacco at the same time. How he negotiated these two digestive actions (which I held to be at alarmingly violent cross-purposes) I could not know. I tried not to think about it, but did. A lot.

Like Stankey, Kidd demonstrates the ability to produce in the reader “two . . . actions” at “alarmingly violent cross-purposes.” This is perhaps nowhere more dramatically demonstrated than in Happy’s piercing assessment of the difference between a vital body and a corpse:

The cliché is that dead people look like they’re sleeping. They don’t. That’s a lie. Sleeping people vibrate despite themselves. . . . Their vulnerability is tender. . . . The dead just look exactly that. . . . They make you want to take them out like the trash. Bury them. Or burn them . . . because until you do it’s that much less possible to remember they were ever alive.

Sarcastic, melancholy, and acerbic Happy may be. He is also an excellent instructor. Throughout The Learners, readers are treated to lessons about the history and practice of graphic design. One comes away with a heightened awareness of how today’s media-saturated environment has evolved and how it operates, and therefore finds himself better equipped to exist in it. These instructional moments may come embedded in dialogue or narration. But just as often Kidd, betraying his designer’s inclination to impart information graphically, distinguishes the material by breaking the formal arrangement of the page. The story itself is interrupted on several occasions for a Learners equivalent of “now a word from our sponsors.” “Content as Irony” is a particularly pithy example. After introducing itself, “irony” proceeds to define itself: “Let’s see, how to explain . . . well, it’s easier by example than definition. Say you come upon a neon sign, brightly lit, that spelled out I HATE NEON.”

The various different charts, fonts, formats, and lists that appear throughout The Learners, suggest to the sensitive reader that the craftsmanship of the object itself deserves consideration. Like a fine artisan, Kidd accomplishes a difficult fusion of form and content and makes the work appear flawless by covering its seams. With language that is simultaneously hyperbolic and subtle, and formal decisions both traditional and unorthodox, Kidd offers his audience a special gift, a book that shows you how to read it, and countless other pieces of media, with greater insight and precision. Read The Learners, then reconsider the cover and ask yourself how an artist can create such subtle image with a palette of black and white. ![]()