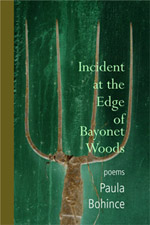

Review | Incident at the Edge of Bayonet Woods, by Paula Bohince

|

|

| Sarabande Books, 2008 |

“[T]he power of storytelling,” Gregory Orr writes, “gives the self/storyteller a sense that he or she is able to order disorder and violence and make sense of it.” Paula Bohince, in her impressive debut collection, writes poems of survival out of the subjects of brutality and grief. The book tells a story of sadness and searching, of the urge to remember and a yearning for grace, as it traces suffering in both the human and animal worlds. No filter softens the lens of hardship, yet for all the heartbreak, these tight and skillfully rendered poems focus on the beauty built from despair.

Set in rural Pennsylvania on a family farm, the narrative comprises three parts. Section One recalls the primary speaker’s complicated childhood, Section Two confronts the circumstances of her father’s brutal death, and Section Three explores her adult life on the homestead. The poems reveal a landscape permeated with loss and violence as they weave together the obsessions of the book. The opening poem, “Prayer,” paradoxically fuses the speaker’s spiritual defiance and longing, juxtaposes tenderness and coarseness, and blurs God with the deceased father:

Adore me, Lord,

beneath this raw milk sky, your vision

of silvery cream comprising daylight.I’ve kept our appointment

in the barn, board after board of pine

hewn by us,sit beside the pig we chose

for his mildness

who smiles, now, in his waste.

The poem captures the friction between past and present and ends with an introduction to the enduring grief that pervades the book:

Something must be wrong

or else you would answer—

my father in heaven who speaks to me

when no one else will speak to me.

As the collection unfolds, the principal narrator explores her complex relationship with her father as well as with characters and creatures that reflect the harsh realities of the setting. There is “Grace, / the valley’s only suicide,” and the robin “in red pajamas like a deposed king” that “belongs to the void now, that prairie, / and is starving.” The speaker also evokes the unsettling memories of ancestors, as in one of the four sophisticated acrostics in the book:

Acrostic: Outhouse

Once this homestead held many children,

uncles and great–uncles, delicate and stooping aunts

tatting lace all day, needles replacing

husbands who disappeared into Bayonet Woods, never returning,

obsession becoming gems of fine knots

until their men thread wholly into white roses,

sadly filigreed, as the wild roses

edging the outhouse are eaten by beetles.

Deceptively simple, this astonishing poem works within its constrained form to span decades and fuse familial stories emblematic of the concerns of the book: the physicality of “this homestead” and “Bayonet Woods,” the undercurrent of violence (“needles replacing / husbands”), and the urge to express beauty (“white roses”) in the face of severity, harshness, and grieving (“sadly filigreed, as the wild roses / edging the outhouse are eaten by beetles”). The strength of Bohince’s collection lies in the speaker’s grappling; often no answer satisfies her as she wrestles with sadness, yet the poems are remarkable for their clarity. In “The Apostles,” she speculates about the events that lead to her father’s murder (“Begin with a paper bag / flush with crumpled hundreds. . . / Then think of those men / who drove up each morning, caps low”) and envisions his death (“they finished him / with one shot through the ribs”), but acknowledges “there is no evidence.” Even without proof, however, she feels confident in implicating the men she believes are guilty, who have “Spent now, what was left of a life— / divided three ways, blown all over town.” Authority and resolve infuse the speaker’s intuition; truth reveals itself in her authentic and persuasive voice, as well as in the voices of the suspects, each of whom offers his own “Gospel.” But where the bereaved daughter is unable to find comfort, the reader often is gifted with lines of heartbreaking precision, like these about her father:

I loved one person all my life.

He who let me hold the saw while he hammered, let me

hold the hammer while he sawed,

his fingers like spigots,who stormed off, jaw tight with disgust

at my incompetence. . .

Incident at the Edge of Bayonet Woods, so rich in the atmosphere of loss and an undercurrent of danger, also is complicated by the uneasy presence of God; there is not so much a question of faith as there is conflict between the benevolent and malevolent ideas of Him. In “The Fish of Galilee,” the familiar biblical account of the feeding of five thousand turns the miracle into an ominous portrayal of sacrifice. The poem’s focus is not on the promise of what is possible, but on the “silver–eyed” fish “handed to knived women,” who perform “[t]he slaughter of thousands.” Throughout the book, the speaker seems drawn to prayer, but her calls are answered by a God who “allotted / for each gift one brutality / for balance,” so that “heaven” is like “all those years spent talking / across the fence / to a woman whose friendship was like being / alone.”

Formally, Bohince’s poems are tight and controlled, sophisticated and economical. They are intense and emotional without ever approaching sentimentality; they look directly into the face of sorrow, but do not create a sense of gloom. In work that feels deeply personal, but universally relevant, Paula Bohince rewards her readers with a world in which desolation is beautiful; this gifted poet leaves the reader “dazzled” by despair. ![]()