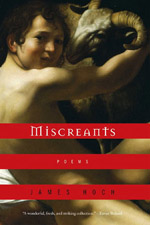

Review | Miscreants, by James Hoch

|

|

| W.W. Norton & Co., 2008 |

James Hoch’s second collection of poetry, Miscreants, opens with an illusion, “a world where a moose / could pull a squirrel out of his hat.” But Hoch does not indulge in sleight of hand to entertain the kids; his magic operates in the world of the occult, of shamans and oracles. And though childhood is one of this collection’s fundamental themes, the overwhelming sensations and obsessions of the book pertain to violence, guilt, transgression, and anxiety—the aftermath of a fractured innocence.

Nowhere are these disquieting themes more apparent than in the second section of the book, “Bobby Almand.” One of Hoch’s peers in suburban Philadelphia, Almand was abducted, raped, and murdered in 1977. In a series of twenty-one untitled poems, Hoch examines how this trauma shaped the landscape of his youth, conjuring as guides the Baroque artist Caravaggio, human grotesqueries from the Mütter Museum, a German locksmith, an unnamed newspaper reporter, and even Almand’s murderer.

In the book’s opening poem, “Acts of Disappearance,” the poet slips a needle into the page, thereby introducing the object that will perform a variety of nominally miraculous functions throughout the collection. The nail that holds together a tree house in “Acts” becomes the syringe that delivers a dose of heroin to another of Hoch’s peers “wrecked on a mattress // in a shooting den off South Street.” And when he removes the needle from that vein, it morphs into the speedometer of the Impala that

took us as far as the salted bridge,

before letting the ride go with a mitten

caught behind the chrome waving

from the other side of the river.

And because so many of the poems in Miscreants are located in the body, in the corpus, the net effect of all these needles, dipped in ink, and given weight, is not unlike that of a tattoo.

In order to makes sense of the chaos of the physical, Miscreants applies the rationality of physics, particularly the equation P = f/a, which says that pressure is equal to force divided by area. Hoch enhances the visceral effect of his poetry with a sharp, spare style; the tight lines often stand alone, resembling the aforementioned needle. This tendency to ratchet up the physicality of verse is evident in the first poem of the Bobby Almand sequence, which begins with “an awful sight,” the image of “a horn / growing out of the head of a woman / preserved in a museum case.” But rapidly, over the space of a sonnet broken into couplets, Hoch manages to overcome our revulsion at his curiosity, our own, and what it has brought us to. He assures us

It’s okay to look. It’s okay to wonder

how the woman slept, took off

her clothes, made love, or answered

anyone crude or curious enough to ask.

Miscreants is haunted by such grotesques. Of the title characters, the “kids wrecked and lovely” with whom he grew up, Hoch laments, “those friends / are gone: some dead, dying, locked up / or jailed in themselves.” But despite the jaded resignation that hums in the background, Hoch leaves open the possibility of redemption. In “Klutz,” an offbeat ars poetica, Hoch demonstrates the wry sense of humor that colors even his most bleak pieces. Before revealing the occasion of the poem, the discord that erupts between two lovers after “the error, the name / that just stumbled out of his mouth,” Hoch characteristically opens with an exploration of language, comparing the word “klutz” to “a jogger with / a strange gait, or an animal that might / benefit from being run over.” With enjambed lines that underscore the clumsiness of the situation, Hoch subtly progresses toward a somewhat hopeful conclusion, asserting more than asking:

What else can he do but reach for her,

as if touch could fix a wrong, and coax her

hand and mouth back to bed, a skill,

the only one he ever had.

Despite a relatively optimistic conclusion, the tentative “as if” betrays a survivor’s reflex toward suspicion. Hoch seems to acknowledge in these lines that his command of language, though deft and impressive, can hardly reconcile a minor trauma, much less the profound tragedy of Bobby Almand’s death. Hoch never doubts the affective power of language. Rather, he acknowledges the danger of speaking, invoking Almand’s killer, “the name in the court record / —Stannard— // he could say things.” Several poems later, the reader is, by means of a slyly ambiguous second person, forced to question what to do if “years later, you are sitting / at The Manor Bar one Thanksgiving Eve //and [Bobby’s] brother walks in.” Hoch concludes with the choking and choked-back couplet: “You want to say something, / then realize and go back to drinking.”

But Hoch does say something, lots of things, in fact. The minor detail of Almand’s underwear, “pulled, they said, back up,” spreads out like a beam of light onto an “unspeakable” violation and leaves the reader distinctly unsettled. It is impossible to avoid the question of whether Hoch partially redeems a horrifying exploitation or partakes in it. Disclosure. Reportage. Analysis. None of these would be enough. But in Miscreants, Hoch offers more. Tenderly and cautiously, in the manner of a tattoo artist, he balances the needle’s simultaneous ability to pierce and to stitch together, leaving us with a raw portrait of violence, images as inescapable as the skin on which they have been imprinted. ![]()