Messages in a Bottle: Notes of an Unlikely Curator

You are going to find that studying Ray becomes a discovery of yourself . . . yet also a revelation

of yourself to others.

—William S. Wilson

|

|

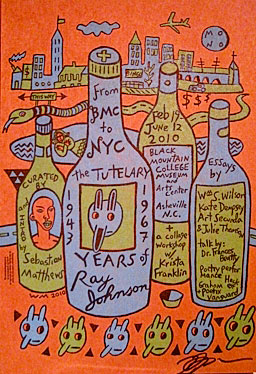

| From BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson (1943-1967) Design, Sebastian Matthews, Bill Matthews Print, Brandon Mise, Blue Barnhouse Press |

|

Note 1

This remark came at a point early in my correspondence with Bill Wilson, a scholar and art collector and longtime friend of Ray Johnson. Because it came both at the beginning of one of his emails and early in the curatorial process, I read it as a warning—a little wisdom from a longtime expert in the field, a curmudgeon’s scold directed at a first-time curator blithely sauntering in. A polite but firm, Don't mess this up, kid.

Wilson was right to warn me. A lot goes into putting together an exhibition, and the task only gets more difficult with an artist like Ray Johnson. The people who collect Ray’s work all have a unique and complicated relationship to the artist. Many of them were his friends, supporters, fellow Black Mountain College students; most want to preserve his legacy and, therefore, despite their generous lending, approached the process with trepidation. Ray’s famously ambivalent attitude toward exhibitions and the art “biz” in general added a whole new layer to the project.

My own sense of Ray Johnson as an artist (and how his work will be considered in the future) was tentative, evolving. No longer do I think of Ray’s famous bunny heads and his mail-art envelopes as definitive trademarks of his work, viewing them, instead, as buds blossoming at the tip of a branch of the flowering tree. Now it's Ray's early love of letter writing and doodling, his dramatic move away from painting—his fascination with glyph markings, cutting up things, his verbal and visual reversals, his incessant punning—that exemplify the fundamental nature of his work.

After receiving Bill’s warning, I spent a year studying Ray, focusing on the time he spent at Black Mountain College and his subsequent move into Manhattan’s East Village art scene. I grew more and more curious about how the artists and fellow students Ray encountered along the way impacted his creative process. I also began to wonder what might be gained by examining Ray’s early output in light of his tutelary influences, the people and places that influenced him the most. What insights might such an investigation afford into the roots of his obsessions, his early propensities, his first major shifts in form and technique? Is the bloom of the latter really to be found in the seed of the former? Why? How?

In a 1972 interview, Ray describes his three years studying at BMC under Josef Albers, Robert Motherwell and others as full “of creativity, inspiration and instruction, personalities and things happening.” [1]

In another interview, Ray said of this time spent at the famously avant-garde college:

My education consisted of working with a hillbilly house plasterer and slagging lime, and doing corners with a trowel, and ceilings, building windows, and putting roofs on a farm house, which is what I wanted to do at that time. I learned a great deal from doing that. [2]

Such comments reveal how ideally suited BMC was for Ray, and how his stay there came at just the right time and place in his development. For, despite being known as a Dadaist prankster later in his career, the young Ray took a pragmatic, single-minded approach to becoming an artist. As one of his fellow classmates said, he blended into Black Mountain College “like furniture.”

Josef Albers preached the art of “making open the eyes” and the BMC faculty as a whole (including Buckminster Fuller, who was attempting to build his first geodesic dome out of old blinds) placed emphasis on the use of materials and ideas that were at hand. This meant paper, leaves and wire for materials and a continuous collaboration of shared thoughts in and out of the classroom. From his teachers, and from fellow students like Ruth Asawa and Hazel Larsen Archer, Ray got just what he was looking for: an opportunity to study art seriously with other artists who were ready and willing to work.

Black Mountain College in the late 40s was a heady, challenging, at times wild place. Amid all the creative comings and goings, a proletarian utopia of sorts formed up in the mountains—a small band of seekers and visionaries busy at the task of educating themselves. Things got spiced up each year when a group of talented and noteworthy artists from New York and beyond arrived for summer sessions. Guest artists were always dropping by (along with a few curious FBI agents) to investigate the mysterious appeal of Lake Eden.

Was Ray ready for everything that came with that enticing package, for such a radical shift in his social environment and personal life? With the unencumbered vantage of hindsight, one thing is clear: Ray’s experience at BMC served as a crucial pivot in his education, the perfect hinge for a major transitional door, which he walked through as student, artist and man. In order to study Ray, I had to examine this pivot, this hinge in his creative life, and use it as a fulcrum around which an exhibition could organize. At first, ideas came as phrases, axioms toward an idea. First it was Life at BMC, then Life after BMC. From BMC to NYC. In short, I had to ignore Bill’s warning—or was it a sly Welcome to the club!?—and jump right in.

Note 2

One morning last summer I visited Bill Wilson in his old Chelsea brownstone. It was a hot day, and I was already sweating when I arrived at his door. After showing me around the main floor (full of books, paintings, photographs, and yards and yards of Ray Johnson archive material), Bill took me down to the basement where he kept many of his Ray pieces in a salon-style display. I’d heard about this “Wall of Ray” but wasn’t ready for the impact of seeing so many of the pieces up close. Bill wanted to hear my ideas for the exhibition, my questions about Ray and how I came to curate the show. All I wanted to do was take in Ray’s pictures, to bask in their majestic presence.

Gradually, Bill and I fell into a rhythm. I’d point to an image and ask questions about it, and Bill would respond, often referring to a collage beside or below the one I had chosen, as it’s impossible to view one image without seeing it in relation to another. He kept up his erudite, switchbacking commentary until lunchtime, always brimming with concepts or techniques he wanted me to observe and to grasp. Up to that point, I’d seen only a couple of Johnson’s pieces in person, having, like most Ray fans, experienced the work as reproductions in a catalog or magazine, or as stills in the documentary film How to Draw a Bunny. [3]

Though the playful gaming Ray is so famous for was apparent at every turn, from my up close and personal viewing, and from listening to Bill’s monologues, I began to appreciate more fully the extent to which Ray had worked the surfaces of his collages. Far from a mere cut-and-paster, Ray painted, scribbled on, rubber-stamped, sanded or otherwise altered each little “piece” of the collage. Bill talked about the “out of focus mood” of the work, how it comes off the wall in subtle layers. I could see where Ray had cut up early BMC-period paintings and “whirled” pieces into a vortex of shape and color reminiscent of the Futurists.

|

| Negroes, Churches, Stars, 1947-48, collage Collection of William S. Wilson |

I kept returning to one piece in particular, a small colored drawing glued on a cardboard square. Undated and titled lightly in pencil at the bottom, “Negroes, Churches, Stars,” Ray had completed it while at BMC. I had to lean in close to see the tiny landscape of mountains made up of primitive human figures giving way to churches with tiny crosses and a star-filled sky. The African-style figures and the churches morph into mountain-forms through a network of obsessively penciled-in bricks and stripes. Hands appear as trees, folds of cloth become mountain ridges. The pigmentation—dark blues and earth-tone red and brown stains—add another layer to the miniature landscape. The jagged edge of the paper itself suggests a mountaintop. Having spent close to a decade in the very same mountains, I most appreciated the “feel” of Ray’s ad lib ridgeline.

Bill Wilson wrote about this piece in an exhibition catalog, noting how Ray

pinpricked the paper to make holes which represent a field of stars. The holes are not the first or last time he reifies nothingness, that is, he uses something to represent nothing, and uses absence to conjure up presence. [4]

4 This comes from a Bill Wilson essay in the catalog The Early Years of Ray Johnson, an exhibit in conjunction with the Richard L. Feigen & Co. exhibition.

For me, that presence is embodied by the young Ray, himself a northern flatlander bowled over by this Appalachian mountain culture. Somehow, this little piece evokes his deep-seated awe of nature and the wild, exotic magic of the landscape that filled his vision. He had been transplanted into a small garden of wild exotics but was looking out on a mountainside filled with rhododendron.

After lunch, I took a few hours away from Bill’s collection to view the Johnson/Warhol/Dali show up at Richard L. Feigen & Co., taking the subway across town and up to E 86th. I only had an hour before they closed, so I rushed through their rooms, taking mental photographs of each image. I returned to Bill’s in the late afternoon to pore through the notebooks of Ray’s early years and to revisit the Wall. By the end of the long day, I’d viewed work from each phase of Ray’s career—a few of his surviving Black Mountain College-era pieces, the early 50s antirectangular moticos, the more complex and worked “tessarae” pieces from the late 50s and early 60s on up through his silhouette and “dollar bill” pieces to the work he made before his death in 1995. When I finally stepped out in the city dusk and began the walk back down to my Aunt Susan’s apartment in the West Village, I was thoroughly overwhelmed and left, literally, speechless.

|

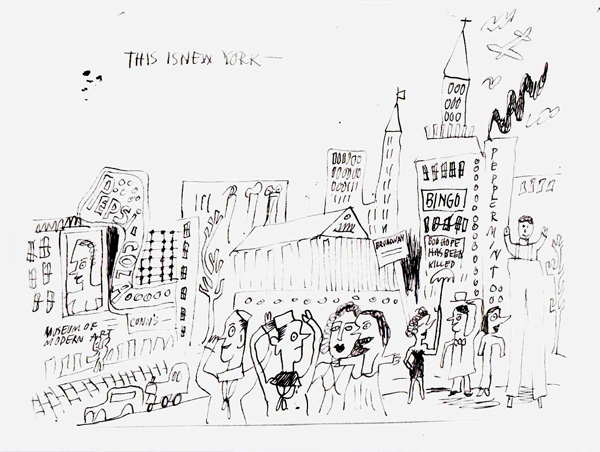

| Untitled (This is New York), 1943, blue pen and ink on paper 8 x 10.4 inches Courtesy of Arthur Secunda |

I had read that Ray didn’t like his work to become fixed or labeled, that he often brought work in a box to show an interested viewer and periodically burned it. What I didn’t realize, until this long day with Bill, was just how far Ray would go to make sure the image—the idea, the perception, the object itself—blurred and changed shape. As I walked down the quickly filling sidewalk, light down at hat level, turning right on Broadway, I could see that I didn’t really know yet just how much of a shifter Ray was, of both shapes and perception. I passed behind a bus and stood a while in the median strip with two women who were out walking their miniature dogs. And it struck me: this was exactly what Bill had warned me about.

Note 3

Organizing this exhibition has involved such surprises, unexpected turns of events and doors opening to unforeseen wonder and confusion. For instance, early in the process, I came upon an article that contained a few images of Ray’s work from his high school days in Detroit. I soon learned that Arthur Secunda, the original owner of the dozen or so drawings, letters, collages, and doodles from the fourteen-year-old Ray was also the original recipient of the work. Soon Secunda and I were corresponding, with me asking him endless questions about Ray as a teen and, not long after, Secunda agreed to let me use his pieces in my show. Before I’d even had enough time to become fully acquainted with Ray in Black Mountain, I was immersed in his earlier life in Detroit.

According to Secunda, Ray was a quiet, shy, serious young man with a sly sense of humor. He attended Cass Technical High School in Detroit and art school in the summer in order to continue studying drawing, design, theory. As early as 1943, Ray wrote letters and made drawings for Secunda—first as notes and doodles in school then as letters and postcards to Secunda when his family moved away to New York. Ray himself has stated that his career as an artist, and his famous New York Correspondence School of Art “. . . actually began in 1943, which is the actual date on those very first letters with drawings and all the other sort of things that I’m still doing today. That was really the infancy of the activity.” Ray goes on to say: “1943 was very important because I found a document in my mother’s scrapbook from 1943 and decided that the things I’d been doing then ought to be cataloged.” [5]

In these early letters/drawings, and in Ray’s need to catalog them, we gain a glimpse into the nature of his main passions as an artist.

|

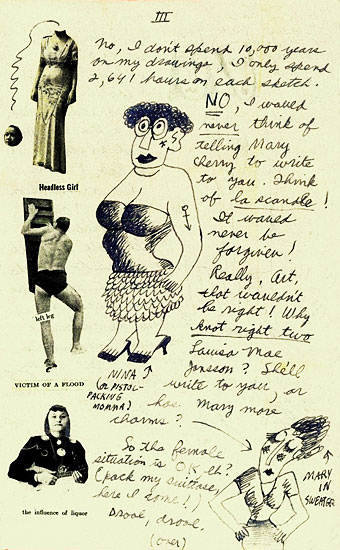

| Untitled (Early Letter Collage), 1943 collage,magazine cutouts, pen ink, 2-sided 9.5 x 6.5 inches Courtesy of Arthur Secunda |

There’s the need to connect with his friends, his loves; the playful voice in the work; his jokey, Dada mindset. There’s the way he so easily weds image and text, and the cartoonist's sense of space on the page. “The idea of third party recipients,” Secunda said in an interview, “was built into the correspondences.” [6] One remarkable page mixes finely-lettered writing with sarcastic and funny cartoon figures, over-the-top imaginative storytelling with wry irony. Along its left side, three wonderfully simple collaged images float, each captioned or otherwise augmented by typed phrases cut from a magazine or newspaper. Indeed, these pages of Arthur Secunda’s, already infused with Ray’s lighthearted but cutting humor, might be examples of his very first collages.

In different ways and at different times, Ray made it clear that he didn’t find his early work anything more than embarrassing, the work of a kid. He gets to feel this way. Looking back at this early work, or the idea of it, he must have felt exposed. Without the ironic and aesthetic distance maturation affords, the work is raw, eager, easily seen-through. In his essay “To Be Sad Because I Was Once a Child,” Mason Klein writes:

in some ways Ray Johnson remained a child, ever invoking the refreshing candor and challenge one expects from children, admitting, in 1968, that ‘I am very close to the child’s world in my creative process. I respond completely to all my instincts and channel them into the work. Never quite out of childhood. It’s very comfortable.’ [7]

This childlike impulsiveness is visible at every stage of Ray’s career, though possibly least so during his tenure at Black Mountain College. There he may have sublimated his own personal desires and fantasies in order to carry out Albers’s object exercises. This may also explain why Ray burned or tore up his old paintings. He had learned what he could from them and thus their “message,” or story, no longer related. He would use their parts to inform his own ongoing narrative, but only by tearing them free from their original context. But what if Ray, a deliberately unfamous artist now famous for mixing up life and art, process and product, never truly matured?

|

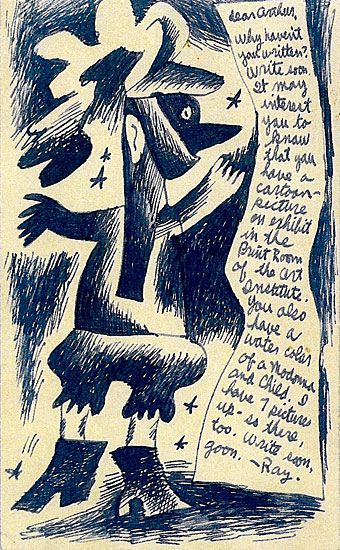

| Untitled (Dear Arthur Scroll), 1943 watercolor and black ink on heavy stock paper 11.5 x 4.5 inches Courtesy of Arthur Secunda |

In another of Arthur Secunda’s letters we witness the process whereby a set of surprising details alters—I can hear Bill Wilson improving this word to “reverses”—the viewer’s first impression of an image. A dancing figure (whose shifty gender is only hinted at by a pair of womanly-looking boots) seems, on first glance, to be wearing some sort of bizarre headgear that resembles an old-fashioned cure for toothache. S/He rapidly morphs into a depiction of sky and clouds sitting on the figure like a crown. Stars reside all around the figure, sparkling like spotlights. The overall impression, when fully digested, is romantic and comical. And the text accompanying the figure reveals that Ray is best pals with Secunda, his co-conspirator. The letter/drawing was created to be received, opened, read and reread. And then answered. Always answered. The whole point of the romance, the comedy, is for its recipient to write back: “Write soon, goon.”

Note 4

With all the myth and lore surrounding Ray Johnson and his theatrical suicide, it may seem to a young artist today that Johnson popped, fully formed, out of the head of modern art. But of course, as with all great artists, the young Johnson had his early influences. There has been mention of Marcel Duchamp’s influence on Ray. I see an equal amount of Kurt Schwitters’s, especially in his concept of Merz, which signifies “an openness to everything.” Schwitters writes: “I could not, in fact, see the reason why old tickets, driftwood, cloakroom tabs, wires and parts of wheels, buttons and old rubbish found in attics and refuse dumps should not be as suitable a material for paintings as the paints made in factories.” [8]

Artists such as Duchamp and Schwitters (as well as Man Ray and others), were embodying all the radical swerves and turns away from their generation’s “dead” art, and had been for some time. So when Johnson made the leap to Black Mountain College, he found that many of its students—under the guidance of former Bauhas stalwarts Josef and Anni Albers and the other brilliant faculty—were deeply involved in studying the European surrealists and their American counterparts. Johnson understood this blurring of life and art instinctually, and so found himself perfectly suited to an environment that encouraged it. As with both Schwitters and Duchamp, the recycling of everyday material becomes a dominant propensity for Ray. But Johnson will not only refuse to give up this approach, he eventually expands and molds it into his own distinct philosophy of reuse.

Back in pre`WWII Detroit, when the high-school age Ray created a set of playing cards entitled first “The Loves of Raymond Johnson” and then “The Secret Loves of Raymond Johnson,” he probably did so with Secunda as audience. Or maybe they were for Ray’s eyes only? In either case, the subjects of these cards were a mix of high school classmates, teachers, Hollywood starlets, famous strippers and comic book heroes. Each card is thin, two-sided, made of old paper stock apparently taken from some company’s tear-sheet notepad. There are twelve images total, each spotlighting a “love” of Ray’s—lighthearted pinups for him to moon over, mock and adore from afar.

|

| The Loves of Raymond Johnson, Card 1, 1943 black ink and watercolor on paper 5 x 2.5 inches Courtesy of Arthur Secunda |

|

| The Loves of Raymond Johnson, Card 2, 1943 black ink and watercolor on paper 5 x 2.5 inches Courtesy of Arthur Secunda |

By combining his classmates and teachers with pop culture heroes like Betty Grable, “spy dancer” Mata Hari and the famous stripper Gypsy Rose Lee, the young Ray elevates his own middle-class life through the power of exotic imagination. With these cards, Ray begins to record his own peculiar “heraldic universe,” (to use a term from writer Lawrence Durrell): a halcyon realm of imagination the artist looks to for inspiration; a filmstrip image that floats over the narrative of the lives surrounding and including the artist. It’s this reel he watches in order to make sense of the human play swirling around him.

In one of his emails, Arthur Secunda refers to “the secretive mode of friendships, fears, [and] unexpressed desires” that he and Ray shared. “In a way,” he suggests, “everything [was] coded against adults.” When I asked why he thought Ray turned to these doodles, Secunda posited:

Ray's correspondence was a cloak, a very clever esthetic discovery of noodling him into the forefront while staying behind a curtain in the wings. It enabled his real life personality to be pure while his art life could be profane and full of wild accepted fantasy. He truly blurred the line between his art and his life. [9]

So, here’s that notion of blur again. Ray is childlike but not a child. He never truly grows up, though his sense of things matures and grows with his experience. He’s incredibly smart, receptive, engaging; his friends love him, even take care of him a little. He stays the same in many ways as an artist, but refashions himself over and over, re-altering his media, his technique and approach. And, from the beginning, he feels comfortable intermingling with the people of his personal world, real and imagined, with the wider world’s macro, popular culture version of itself. I believe that it is with these cards that Ray first discovered the heart of his approach and the source of his obsessions. When in need of inspiration, Ray could always turn to and tap into the creative realm of his Secret Loves playing cards. These “playing” cards (as well as all the letters and postcards he wrote to Secunda at this time) are the spring out of which all of Ray’s work gushes forth.

Note 5

The jazz critic Ted Gioia, in writing about improvisation, posits that

only a particular type of temperament would be attracted to an art form which values spur-of-the-moment decisions over carefully considered choices, which prefers the haphazard to the premeditated, which views unpredictability as a virtue and sees cool-headed calculation as a vice. [10]

This sounds a lot like the nature of collage making and, in particular, Ray’s approach to creating art. As opposed to what he calls the “blueprint” method, Gioia talks of another “retrospective” method, and says that in it

the artist can start his work with an almost random maneuver—a brush stroke on a canvas, an opening line, a musical motif—and then adapt his later moves to this initial gambit. [11-kill this note which simply reads "And here too"--mak]

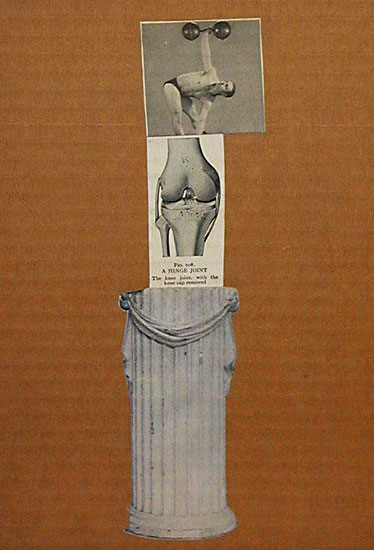

Such a methodology is immediately apparent in Ray’s 50s-era “Moticos with Joints,” a relatively straightforward collage made up of three simple pastes featured in the stunning Richard L. Feigen & Co. exhibition.

|

| Untitled (Moticos with Joints), ca. 1954-55 collage on corrugated cardboard 15.75 x 12 inches Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. |

It’s easy to picture Ray laying down the image of the column then placing the “hinge joint” image above it. In order to complete and complicate these first two moves, he selects the barbell-toting strong man image to go on top. With the addition of the hypermasculine figure comes the visual joke: the three separate pieces become a unified whole, with the torso becoming the column’s head, the barbells the eyes. Underneath all this play, Ray seems to be holding up bodybuilding culture—and possibly the gay culture that puts it on a pedestal—in order to mock it. [12]

Bill spoke during our first visit of Ray’s propensity to make such tertiary, lateral moves out of a collage pairing: the third movement coming in to alter and confuse the dialectic. The energy embodied by these two forces in direct relation to one another (lovers making love, an apt metaphor, or a good conversation over wine or coffee, one color set beside another) is released by the entrance of the third force into the field of reference. In fact, there’s no field at all until this third force triangulates matters. Another lover comes into the room. The metaphor, now activated, undresses itself. The night's talk explodes when the check arrives. A slip of red undermines the agreement made by blue and green. Strophe, antistrophe, epode.

|

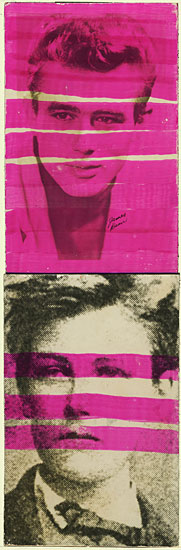

| James Dean/Rimbaud ca. 1956-58 collage on cardboard 11 x 7.65 inches Private Collection |

In his essay, Gioia completes his thought on improvisation: “The improviser may be unable to look ahead at what he is going to play, but he can look behind at what he has just played; thus each new musical phrase can be shaped with relation to what has gone before.” [13] Ray used pop culture’s trash and pulp to make something new, just as the bop musician takes an old standard and stands it on its head.

Note 6

Ray, like many artists before him, used Black Mountain College as a springboard to propel himself into the Manhattan art world. Thus a pivot turns out to be a launching pad as well. No coincidence, then, that Johnson made this creative leap during his transition from Black Mountain to New York City while hanging out with old BMC buddies. Isolated as it was in so many ways, Black Mountain College must have seemed a bit of a mirage to Ray. For such an event-based artist, BMC’s late night dances were great but couldn’t beat the Ur-city’s cornucopia of experiences that fed Johnson with such abundance. (Though, in both instances, he was surrounded by artist friends and mentors, and immersed in their respective scenes.) “With Manhattan as his field,” Ray’s old friend Bill Wilson writes, “Ray was disciplining himself to find uses for almost any accidental event.” [14]

An autodidact in Zen and a self-described disciple of John Cage’s cultivation of chance occurrence, Ray was ripe for the challenges and experiences Manhattan had to offer. He had been trained by BMC to adhere to a rigorous work ethic and, having been brought through a sort of secret society of intellectuals (a “cult of friends,” as I have come to call it), he knew how to establish a network of friends to support, challenge and nourish him. With each geographic move Ray made, he encountered new materials, new friends inside a new scene, a new landscape to explore. As he passed into and through these realms (for one new move suggested the next), he began the lifelong process of accruing and cataloging experiences, people, names, objects of all sorts, juxtapositions, moments, and ideas, and turning them into material for his art. He began cutting things up and rearranging fragments to fashion an image of or fill an envelope with his uniquely calibrated responses to a friend or a new acquaintance or a public figure he had a crush on or thought ridiculous. Then he’d send these things off, hand them off, urging his recipients to make the next connection, the next move.

|

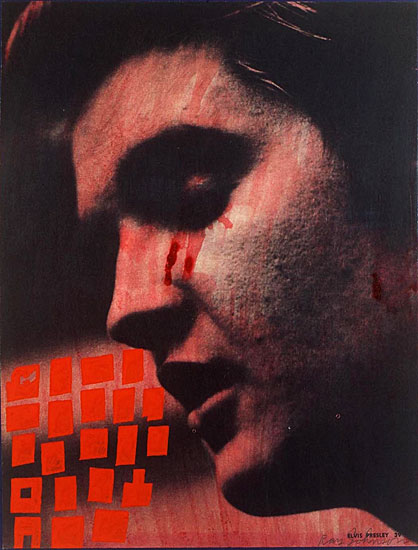

| Oedipus (Elvis Presley #1), ca. 1956-57 collage 10.75 x 7.5 inches Courtesy of William S. Wilson |

It wasn’t long before Johnson started combining his newly cut-up canvas strips with text and images from popular culture. (This was the early Fifties, way before Warhol became King of Pop.) It’s as if Ray incorporated Albers’s ideas then left him behind. Ritualistically, Ray made sure to rip up his novice work and to reincorporate it into new projects. Sometimes burning it, sometimes sending it out to strangers, often delivering it into the sea in neat packages cast off the late night ferry out of Manhattan—his messages in bottles—Ray was always searching for ways to regenerate the creative spirit.

|

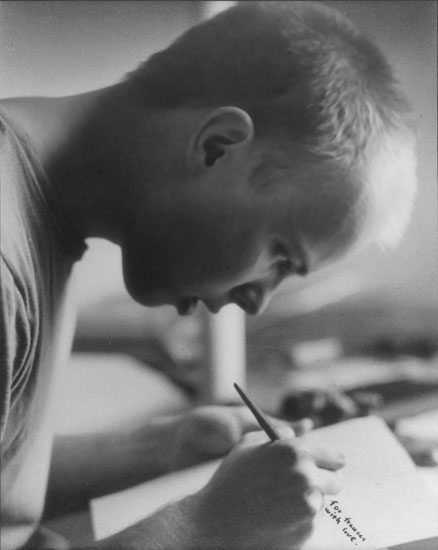

| Hazel Larsen Archer, Untitled (Ray Writing to Frances), ca. 1945–48, Gelatin Silver Print 8.75 x 5.75 inches Courtesy of the Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer |

There's a fabulous photo by Hazel Larsen Archer taken during her days with Ray at Black Mountain. In it, Ray is writing out a note to his buddy Frances X. Profumo. The page is blank, as though his mind is blank, and the words he pens carefully there serve as his entrance: “for Frances, with love.” By evoking his connection with Frances, Ray accesses the realm of artful play, playful art-making. The Gods of the Threshold accept this offering and Ray is off, moving on to an image hidden from our view by his drawing hand. He has used his friend (his care for, his interest in her) as his Muse. Now he is ready to begin.

In this photo Archer has captured the inwardness of Johnson’s creative process in process, his intent focus upon “the plane of the daydream” and not merely the facts of childhood. [15] Ever creative, Ray never stopped talking to himself, never gave up daydreaming, never forgot to invite others into the play. But, for Ray, connecting to others is always also about connecting back to himself. Friends were vehicles for Ray, ways to help him explore his own complicated sense of self. He used friends like Norman Solomon and Dorothy Podber as a way to make more art, but he gave them gifts in the process and urged them to respond. You could say, exaggerating a bit, that everything Ray did was a love letter and a self-portrait.

But a self-portrait intimately determined by the environment surrounding it. So when I ask, Did Ray’s move from BMC to NYC, from country to city, change his art? I am beginning to delve into his creative method. His materials change with each new move, but, with each paradigm shift, we also witness the modulations of Ray’s spiritual qualities. The simple fact that there is a larger array of junk to collect in the city than in the country helped facilitate Ray’s shift away from painting to collage. But this shift also has to do with him emerging from Albers’s shadow. Ray breaks with the past by stepping through the door of the present.

Note 7

A few months after my first visit, I returned to Manhattan and visited Bill at his house, once again immersing myself in his extensive Ray archive, stealing an hour down at the Wall (altered somewhat due to another exhibition Bill was lending to). Bill was in good spirits, happy that I had better questions to ask, more pointed concerns at the ready. His assistant, Michael, helped me find my way through the archive folders. I even got up the nerve to ask Bill to lend pieces for my show.

|

| Marianne Moore, 1963, collage 6.65 x 3.25 inches Collection of William S. Wilson |

Again, after lunch, I went back up to the Upper East Side to catch another glimpse of the Ray show. Luckily, Richard L. Feigen & Co. had extended the run. I had more concentration for the exhibition, and spent time with the earliest pieces, probing them for clues, ideas, secret codes. The Director, Frances Beatty, had agreed to show me some of Ray’s work from the BMC-era through the early 50s. She walked me up a spectacular spiraling staircase to the top floor, which felt like a penthouse apartment in an Audrey Hepburn movie. Then Frances sat me down without fanfare in front of two of Ray’s earliest surviving paintings, “Seven Ladders” and “Calm Center.” The last I heard they had been in the possession of Ray’s longtime friend and lover, Richard Lippold.

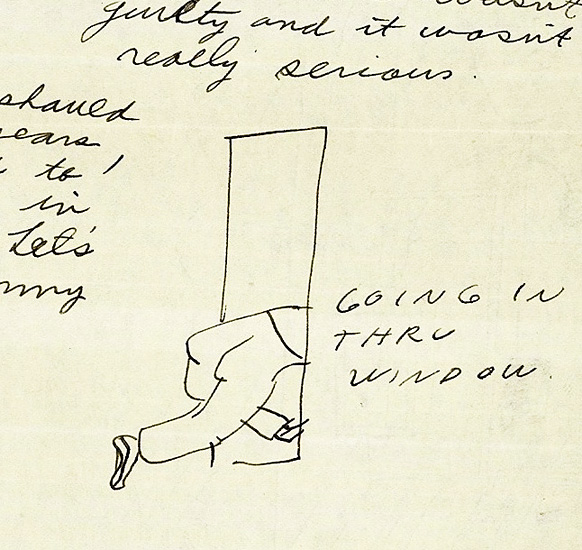

But here they were. I sat in front of them and tried my best to take in the awesome intensity their geometric shapes and brilliant colors presented. Frances’ assistant, Jennifer, brought out a colorful array of early 50s moticos and leaned them against the wall, in some cases stacked two deep. I stayed until closing time, lost among Ray’s works, up in that stunning space, at times talking with Frances, others just sitting alone taking notes. At one point, Jennifer showed me a closet full of old notebooks that Ray had kept at Cass Tech. There were letters, too, written home to his parents during Ray’s time at BMC, full of good will and optimism, and bristling with eagerness to move forward in life and work. One note suggests he was heading to California to attend an art school recommended by Albers. Another letter home—a menagerie of Thurberesque drawings depicting his misadventures with friends—had been penned with Ray’s neat lines stacked tight together but with stretched out letters across the page.

|

| Letter with Two Drawings, ca. Fall 1945 (detail) drawing 8.5 x 11 inches Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. |

It was becoming clear that Ray, first in the tight cabal of Black Mountain College, then in the downtown Manhattan art scene, reacted to and created from the people and events swirling around him. “Walking down the street with Ray Johnson,” says photographer Billy Name, “all of a sudden you see the world as this wonderful, delightful, joyful, playful place and it doesn't stop . . . you became part of this joyful world that he lived.” [16] Seeing these important early paintings, so clearly under the influence of Albers, then taking in the moticos Ray made five or six years later, it seemed obvious that in order to fully emerge from Albers’s influence Ray had to begin to reapply his old high school games to Albers’s rigid, breakable exercises. But hadn’t they been constructed to be taken apart in the first place?

Marie Tavroges Stilkind, in a recent email, told me the following story about Ray:

I would have my lunches . . . with Fluxist artist Albert M. Fine, who was then a grad student at Juilliard, and we'd go out to the little park on the Hudson next to Grant's Tomb. Once we opened up the box of envelopes, given by Ray to Albert to give to me, and as we looked at the contents of the envelopes a great wind came and blew all the contents all over the park, lots and lots of clippings from newspapers . . . I was distressed and felt we ought to round up all the clippings and put them back in the envelopes but Albert said, ‘In the great scheme of things, they probably weren't important.’ And then in that Zen moment we both laughed and laughed. When we told Ray about it later, he just smiled . . .

The wind was real—the bits and pieces fly into the air and go somewhere else, equally important and unimportant. [17]

|

| Calm Center, 1949–50 oil on cardboard 28 x 28 inches Private Collection, Courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. |

Looking at Calm Center all alone up in that top floor apartment, the old painting leaning there like that with a slightly damaged corner, I couldn’t help but think I was hanging out with Ray himself. Its grid of colors seem to represent all the different ways of Ray, all his different selves, and that black square at the heart of the piece, its calm center, was the nothingness around which all his personality swirled. I often picture Ray this way, leaning up against that wall, calmly breathing in and out the dust-particled air, emptying so to fill again. And I only half remember walking down those spiraling marble stairs, my own footsteps lost to me as I descended to the street, making it to Park at dusk, raising my hand for the next cab.

Note 8

It seems I have fashioned this piece into a seesaw: a middle section hinged between two three-section units. Ray’s time at Black Mountain College as the fulcrum: Cass Tech on one end and Manhattan on the other. City, country, city. When I sit on one end, the other pops into view. If I stay in the middle, I can find a balance point where everything falls into alignment. I ridge-walk back in my mind to the beginning then hike forward examining all the surfaces and subtle layers—the references, the repetitions—and by the time I have made it to the end, maybe I have gained a little insight. Then I go back to the beginning and try again.

My hope is that, after viewing this show or reading this catalog, my imaginary viewer/reader will face Ray’s work (in other exhibitions, on the web, in books, magazines or movies) with a fuller sense of what Ray was attempting when he sat down to make art, when he prepared to send his work out to be received, passed on, altered. I want their enjoyment to grow the more they notice Ray’s moves, his endless jokes and throwaway gestures, the more they catch him in the act. That act of throwing things away is key. Not getting too caught up in finding meaning in every little detail, but rather catching Ray’s drift, his mood, and following it in. If you let Ray work his magic, that work shows you how to see.

|

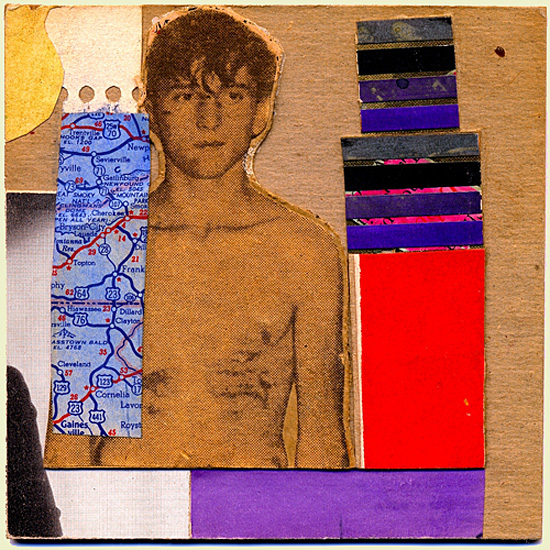

| Untitled (Young Man with Map), n.d., collage 4 x 4 inches Courtesy of the Estate of Frances X. Profumo |

There’s an early collage of Ray’s, made for his good friend Frances X. Profumo, which, judging from the places depicted in a map fragment it contains (Cherokee, the Great Smokies National Park) was completed during or soon after his time at Black Mountain College. Two sets of color bars to the right of the figure certainly show aspects of Ray's time working with Josef Albers and his color exercises. A collage piece is hidden underneath these bars. A red highway line in the map morphs into the young Ray’s collarbone. An easy read of the piece, maybe too easy, is that Ray has BMC in his heart (because that's where Black Mountain resides based on the physical placement of the map) and that Albers is both at his side and boxing him in. The collage telegraphs the fact that there are aspects of Ray's work hidden under, and perhaps obscured by, his interest in Albers’s ideas about color and design.

Note 9

I have just walked back down Broadway, exhausted from my first day with Bill Wilson. I have stumbled upon a hip-looking West Village cafe and joined a few solitary souls up at the bar. I am sipping a dry gin martini for fortitude, writing down titles for mini essays I wonder if I’ll ever write. Note 1. Note 2. The world around me seems altered to my sight: Everyone a cut out fragment pasted to a color block. Storefronts are frames waiting for more glyphs to suspend themselves in their ether. I attempt to jot down stray fragments of what Bill Wilson has told me. The way Ray jumps from a last name like Coffin and makes it coffee then adds and doughnuts and, and . . . . How one collage can be a response to a previous note from a friend, a reworking. How water runs through Ray’s work in a motif current. How Ray used to walk through the East Village with “duck” tape on his mouth.

I remember the photo in Bill’s hallway of a stone wall, Ray's head and elbow gradually appearing as faux-stones at the top of the stack. In another photo, Ray stands between two billboard Os, insinuating himself between them, turning himself into a letter. And I think of Bill, picturing him down in his basement, surrounded by Ray’s work on the walls. He’s just come down the steep stair, gripping the banister at each step, finally plopping down into one of the two chairs set up in front of his Great Wall of Ray. He tilts his head, hand on brow, and, sighing asks: “What are you looking at now? What shall we discuss?”

And I think of Ray throwing himself off a bridge into the cold waters of Sag Harbor, of his empty house filled to the brim with his art, his life, arranged in a grand suicide note. And I think of my own show, worried I won’t be able to do Ray justice. I don’t know enough. There’s not enough time. But then I remember the note I stumbled upon earlier that afternoon, jotted on the back of early drawing made for Ray’s friend, Suzi Gablik. Ray has quoted Rimbaud in elegantly lettered pencil: “i stretched out ropes from spire to spire; garlands from window to / window; golden chains from star to star; and i dance.” [18]

|

| Exterior of Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center Photo by Charter Weeks, 2010 |

Last call. I shuffle back to my aunt’s apartment and climb onto the couch to sleep, seasick with brain whirl. I remember the story Bill told of going to some tough wharf-side bar with Ray and watching him take the place in, detail by detail. How he scanned the place, on the scout for things to happen, not wondering where he fit in, just how he might “be” in and, being there, open to what might happen.

I awake sometime around two to find the ceiling above me draped in the night shadow of undulating trees. They broadcast their underwater images on the screen above and slip down the wall to encase the open space in a net of glyphs and watery letters. And I dance. ![]()

All images used with permission of the Ray Johnson Estate.