Flights Out, Flights In

What follows is a tracking of two impulses that guide me when I’m writing: a turning outward to the world off the page and a turning inward to the crafting of the poem at hand. To keep this mapping of my process grounded, I’ll stay specific; I’ll describe how the poem “Ephemera” found its shape.

Out →

In his keynote address at the 1992 OutWrite Conference, Melvin Dixon said, “I’ll be somewhere listening for my name.” He died that same year of AIDS. I first encountered a print excerpt from his address in the journal Callaloo. I was twenty-eight. I had never heard of this writer before. What did I know of my GLBT literary history? Of my herstory? (Maybe this is where some poems begin—in heartbreak?)

I had been trying that same year to write about my great aunts, the two “old maids” in my family—one my relative by blood, the other her companion of forty years—but there were so many dead ends, so much I didn’t know, couldn’t know. (Or a poem opens its field when I’m ambushed by questions?) Reading Dixon, I wondered if Peg and Dorothy were out there, too, listening, waiting for someone (me?) to sing their names. (Sometimes a sense of accountability to someone or something larger than myself incites the process.) Later, I wondered if I was hoping to rescue a lost history, or hoping for a lost history to rescue me. (Maybe my ambitions aren’t so heroic, after all.) Not to mention, I’d been reading Judith “Jack” Halberstam’s In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lines, which had me asking all sorts of hard questions about the ethics of archiving and how time is socially constructed. (And reading, of course, spins me further outward.)

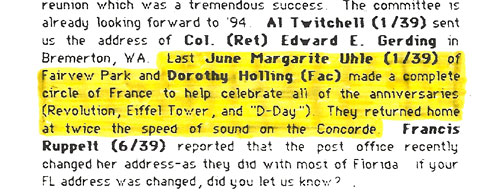

As an exercise in desperation, I typed the full names of my two aunts side by side into Google. (Much of my process goes like this. I’m chasing after something, often in vain, often in circles, turning everywhere but the page. This, too, I call writing.) I had one hit in cyberspace. I stumbled upon an electronic copy of a school alumni newsletter dated December 1989 in which this piece of news was printed:

|

I couldn’t have invented more uncanny details: that phrase “celebrate all the anniversaries” and the image of two lifelong companions at the ages of sixty-eight and seventy-five breaking the sound barrier on a Concorde jet.

In ←

When I started drafting “Ephemera” I wondered: could I use the sentence as a vehicle for time travel? Could I use syntax to capture the disorienting effects of queer time? (Ambitious, I know, but I’m always curious about the limits of language, regardless of whether or not I’m able to successfully test those limits.) I had Larry Levis’s “At the Grave of My Guardian Angel: St. Louis Cemetery, New Orleans” in mind as a model—a long, leapy poem populated with a number of historical characters including Walt Whitman, Abraham Lincoln, Mikhail Bakunin, and Lee Harvey Oswald. (Often when writing, I can’t help but converse in my head with poets who’ve written poems that amaze me.) If you read “Ephemera” side by side with Levis’s poem, you’ll catch the echo. For one thing, I tried to do with a coin what Levis does with a rake. I was wowed by the way Levis used such a quiet image to make such a giant turn across time and space:

Like the tines of a rake combing the battleground to overturn

Something that might identify the dead at Antietam.

The rake keeps flashing in the late autumn light.

And Bakunin, with a face impassive as a barn owl’s & never straying from the one

true text of flames?

And Lincoln, absentmindedly trying to brush away the wart on his cheek

As he dresses for the last time,

As he fumbles for a pair of cuff links in a silk-lined box,

As he anticipates some pure & frivolous pleasure,

As he dreams for a moment, & is a woman for a moment,

And in his floating joy has no idea what is going to happen to him in the next hour?

And Oswald dozing over a pamphlet by Trotsky in the student union?

Oh live oak, thoughtless beauty in a century of pulpy memoirs,

Spreading into the early morning sunlight

As if it could never be otherwise, as if it were all a pure proclamation of leaves & a

final quiet—

The image of a rake overturning dead Civil War soldiers is chilling. Even more haunting though is the way Levis unexpectedly shifts to present tense via the image of the rake: “The rake keeps flashing.” He doesn’t end his play with temporality here. Once Levis has the reader in this illusory space, in the present tense still dwelling on the past, he raises the poem’s dead—“Bakunin,” “Lincoln,” and “Oswald”—and the poem’s living—“Oh live oak.” He creates this effect by utilizing the present participle verb form, placing each of these characters in a state of continuous action: “Bakunin . . . never straying,” “Lincoln . . . trying to brush away,” “Oswald dozing,” and “live oak . . . Spreading.” Like ghosts, these characters simultaneously inhabit the image of the dead being overturned by a rake while also inhabiting a range of continuous actions in the present tense. (Ultimately, I believe the inside mechanics of a poem can be just as magical as the uncanny details in the world.)

I hoped to create a similar effect in “Ephemera.” (This took a lot of tinkering.) In a scene that describes Peg and Dorothy undressing at the day’s end, a “gleam” of skin is compared to a coin still in “mint condition.” Like the rake, the quiet image of the coin becomes the agent that shifts the poem’s tense from past to present:

Gleam of skin of a body surviving time,

Still in mint condition, now lifted, in soft light, like a rare

Coin from its sleeve.

In my palm, a copper penny still gleaming.

And my lover with a look of mischief walking closer.

And Melvin Dixon too exhausted to translate Senghor.

And Melvin Dixon while hearing a voice, suddenly, lovingly calling his name.

And Peg dragging her schnauzer out for an evening walk,

And Dorothy ordering a steak well done,

And a small girl with eyes bent on a rerun of Robin Hood, longing to vanish in

the forest

Drops her knife at the kitchen table to announce, Call me Bow.

Here, too, I used the present participle form, the continuous grammatical moment, to unify characters across time and space: “my lover . . . walking closer,” “Melvin Dixon . . . hearing a voice,” “Peg dragging,” “Dorothy ordering,” and “a small girl . . . longing to vanish.” My intent was to use image and syntax (just a few of the tools at my disposal) to make distinct strangers in time—even if only briefly possible within the boundless world of the poem—simultaneous travelers. ![]()

Contributor’s

notes

Tracking the Muse