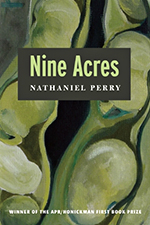

Review | Nine Acres, by Nathaniel Perry

The American Poetry Review / Copper Canyon Press, 2011

|

“Should we love each other / only at our loveliest, or speak / of stars just on the darkest nights?” asks Nathaniel Perry in Nine Acres. The poems in his debut collection consider what it means to be faithful—as husband, father, neighbor, and as steward of land, poultry, orchard, and garden. Written entirely in the same received form of rhymed quatrains, they confront the passions, tedium, graces, and sweat labor of such fidelities both thematically and structurally.

The fifty-two poems all take their names from the chapter titles of horticulturalist M.G. Kain’s 1935 book on small-farm management, Five Acres and Independence, yielding poems called “Green Manures and Cover Crops,” “Essentials of Spraying and Dusting,” and “Small Farm Fruit Gardens.” Exactingly faithful to his task, Perry even named the book’s final poem from a chapter omitted from subsequent printings of Kain’s book, which he discovered as a “ghost print” in his own 1940 edition.

If the titles seem prosaic, the poems themselves certainly do not. Images spiral and accumulate, incrementally, each one complicating the previous one. In “Figures Don’t Lie,” a field full of hay bales under a night sky yields a startling comparison to stars:

Nights we notice the field hinged

to stars, or to the field the stars

are set on. In our earthly field,

hay is still baled and waiting farin the distance, and so I say the stars

are fire baled.

Nine Acres encompasses the narrative arc of a year spent tending a garden and young family. Its neatly shaped quatrains remind this reader—no relation to Perry, by the way—of intensively planted vegetable and herb beds, typically laid in four-by-four-foot plots “like soil squared / and measured into beds by a man // sweating through his shirt with effort”. Burgeoning and mysterious as any bountiful garden, the poems comprise sixteen lines in four stanzas of four lines each. Moreover, almost every line contains four beats.

In mythology and literature, the number four symbolizes stability, order, and the earth itself. Perry’s four-square poems serve as fitting containers for his subjects of rural life and growing a family, affirming critic Helen Vendler’s words that “a writer’s true ‘vision’ lies in the implications of his or her style.” An old-fashioned sensibility permeates this work—a reaction to our times, perhaps, Frost’s “momentary stay against confusion.” Like Frost, Perry stakes the rural landscape as the territory of formally written poems that confront the natural world in plainspoken language. Writing in the Winter 2010 issue of The Hampden-Sydney Poetry Review, which he edits, Perry has asserted:

the modern world has grown out of touch with nature and most everything else important, and poetry. . . can provide a needed and often urgent reminder that the world is more than the world we make. Poems traffic in mystery, and the world (especially the natural world) is mysterious.

Perry reveals his fealty to form and its mysteries and foreshadows some of his recurring themes and characters in the frontispiece poem, “Introduction.” The poem opens cinematically, announcing itself as a made thing, in the first stanza:

I’ll start this with an ending, or something

like an ending, at least there’s tension and fading

light. In the back field, our neighbor

Lee’s long field behind us, we were sliding

The speaker, out for a walk with his son and dogs, encounters a coyote at the edge of the woods. It is dusk, a liminal time. The coyote, “bright as tomorrow, opened and shut / and opened again the woods’ dark doors / then stilled to stand and look at us.” This trickster figure of Native American mythology typically delivers surprise, sometimes a lesson. Perry writes:

I tried just to read the animal’s

face. But all I got was the starkness

of form: that which hunts before me,

that which is not dark in the darkness.

Here the coyote is the form itself, opening and shutting the “dark doors” of the writer’s subconscious, teaching where to go, bringing out of the darkness, “that which is not dark.” There’s a Grimm’s-fairy-tale quality to the notion of forest doors that open and shut, adding to the mysteries that form can invoke. The rational layers of mind can easily slip away, walking in the woods. Encounters with wild creatures can take on qualities of the totemic, as seemingly happens in “Live Stock”:

Thrushes, in handfuls, candle up

into the pines and ask what wonder

I thought it was I wanted.

The constraint of writing in form, of having to fit words within a tightly prescribed pattern, can often create surprising images that jolt themselves out of the writer’s deep-buried places.

I’m lost in the pattern of walking this field,

where nothing grows the same each year,

though even that is a kind of yield.

In the same way, the constraints of marriage, of parenthood, of tending a garden can open into their own graces, mysteries, and tenderness. “Seeds and Seeding” begins with the act of “shaking seeds into their furrows” on a cloudy day that turns into a thunderous night—“the rain, the wildness, doing / and undoing, slow hands unpinning”—made erotic, “where the part / we’re meant to play is a mystery, / and everything is about to start.” Other poems encounter marital undertows, such as when, in “Frost Damage Prevention,” “Our old fights / float down from the same events the way / frost bows autumn beans in the night”, as well as in “Capital”: “joy, / a little drummer rocking around / the dogwood, or just a little boy.”

Perry’s poems often come to a sonnet-like turn or volta, a moment of truth. In “Small Farm Fruit Gardens,” a nod to the eclogue, this volta becomes a literal hinge in the middle of the poem, an insomniac moment: “I / am left in shadow’s shadows to stand // too still and figure all the turnings / turning us, or where we’ll turn.” Ultimately, the speaker addresses the moon, begging in a litany of endearments: “Come back little moon— / dark night’s noon, heaven-raker, / cloister-maker, buttonhole, bloom.”

These turns often create aphorisms. “It’s not that we get what we want exactly, / but that want, if we want it, is all we get,” concludes “Compost,” a meditation on desire. “In dirt is one life we can choose / to make,” the speaker asserts in “Soil Surface Management.” “The sweetness of decline—fall’s little / ditty, where mercy rhymes with fate,” the speaker avers in “Selection of Tree Fruits.” The ending couplet of the last poem in the book, “The Farm Library,” takes on the weight of the author’s entire project, in life and work: “That in seed and land we find an anchor, / and in language we weigh out our courage.”

Perry addresses the dangers, complexity, and toll of modern agricultural practices in Nine Acres, but delicately, with real respect for the farmers who practice it. “Lee’s putting poison on his corn. / Though I’d never raise the issue, I try / not to think what else is in his creek,” the speaker begins in “Essentials of Spraying and Dusting.” This speaker would not impose his viewpoint on someone whose family has been farming their land for generations, who lost and bought back their land, who “told me he can’t / farm it alone anymore.” No one ever said farming was easy. “The ground shows little of what we’ve done, / but insignificance, I guess, // is still a signal of some kind; / our secrets, hidden and so unharmed, / we’re sure will soon transform us.”

“When we were new, or smaller-hearted, / we did not care at all for the few // things that matter to us now,” Perry writes in “Vegetable Crops to Avoid and to Choose.” The payoff may not be material. But there are other rewards to consider, contrary as they may seem in today’s culture of consumption: “to see this place filled / by something that is not us, our every / acre ringed and shrouded and still.” ![]()

Nathaniel Perry is the author of one collection of poetry, Nine Acres (APR / Copper Canyon Press, 2011). He is an assistant professor of English at Hampden–Sydney College, where he is the editor of The Hampden–Sydney Poetry Review.