print preview

print previewAnderson House 212

Lauren Miner was one of the photographers who documented Claudia Emerson’s working and writing spaces at the request of Emerson’s husband, Kent Ippolito. Miner was also a poetry student of Emerson’s and pairs documentary photographs here with memories of meeting with Emerson in this space.

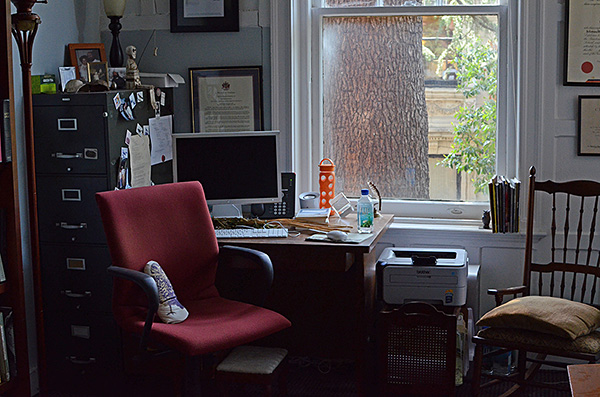

As one of Claudia Emerson’s students, I remember meeting with her in the office on the second floor of the historic Anderson House on Richmond’s West Franklin Street, one flight up from the room where, in the spring of 2014, we held our graduate poetry workshop. I don’t think she ever wrote poems there; she had a designated room at home for that. This office served as a kind of on-site base camp for her teaching, and she furnished it specifically for that purpose.

|

I often thought of this place as a sanctuary—a quiet, optimistic space. The room—a narrow rectangle with only two windows—was dark, so Claudia put her desk at the farthest end, where she could enjoy the most natural light. She would offer students the rocking chair in the corner; she took the rolling chair beside her desk.

|

On the day of the photo shoot, her desk appeared unchanged—except for the dried bouquet of long-stemmed flowers someone left (the card unsigned) that had been propped against the office door. Behind her monitor, out of sight, she stashed some of the more utilitarian teaching necessities: a toothbrush, some snacks, a dry-erase marker. There, she also left a stack of papers, including a classroom roster and a brief biographical sketch of Natasha Trethewey.

|

The short stack of books beside her keyboard and her water bottle were some of the titles she had planned to use in her fall 2014 undergraduate classes; The Poet’s Heartbeat was listed on the syllabus for her spring 2015 graduate form-and-theory course.

|

When I sat in the rocking chair, facing Claudia, I also faced the bookshelves against the wall behind her. Here, she kept the works of canonical poets—such as Dickinson, Whitman, Eliot, and Plath—but many of the authors (and, for the literary journals, editors) were her colleagues and acquaintances, if not personal friends. Some of these books accompanied her down the stairs to class; others were available to reference during conferences, as needed.

Once, after she had recommended a particular book to me several times, I asked if I could borrow it. She searched these shelves but couldn’t find her copy. She looked again when she got home, and when she still couldn’t find it (suspecting she must have loaned it to someone else), she bought a new one and gave it to me. Over and over, Claudia surprised her students with such gestures of generosity.

|

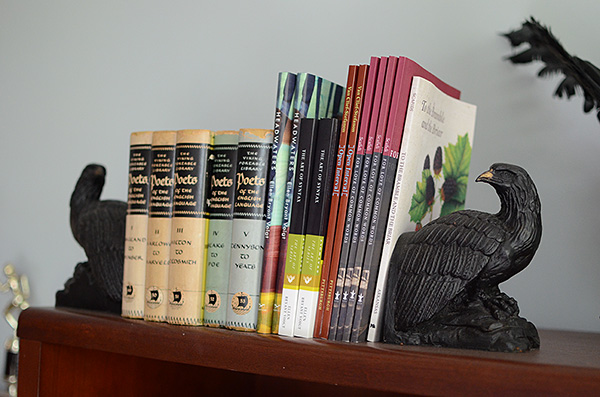

On the top of one bookshelf, between a pair of bookend birds, she kept a stash of books we read in the spring 2014 graduate workshop. For this particular course, she refused to give us the list in advance, or to itemize it on the syllabus. Instead, she provided the books herself, distributing them only a week (or so) before we would discuss them. We read the works in pairs—two books by each poet—as a method for discussing both a single collection (as a self-contained work) and the conversations among a wider range of poems by the same maker. Because Claudia herself often worked in sequences, and because she had an abiding interest in the crafting of a poetry book (as an art object amounting to more than an accumulation of individual poems), she found a way to bring her own creative concerns into the classroom and challenge us to think about our own work in these ways.

|

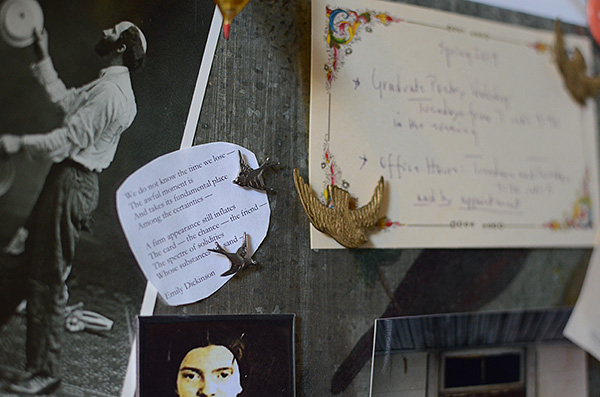

On the opposite wall, facing these books, was the office fireplace, another set of bookshelves, and (below a large picture of William Faulkner) an enormous antique dictionary on a squat wooden table. The display of objects on the mantle—a visual focal point in the office—seems to represent the spirit of her character as much as any other area of the room. Here, she put some of her books about nature writing (held between another pair of birds), an antique edition of Leaves of Grass (a gift from a former student), a weathered turtle shell, a pristine snail shell, a clock, and a small figurine of Harper Lee holding a miniature copy of To Kill a Mockingbird—which, most of Claudia’s students know, was one of her all-time favorite books.

|

Claudia would often encourage us to follow our curiosity, to see where it might lead. She often spoke of her vision for an interdisciplinary course, where creative writing students would enroll in a biology class, do all the regular coursework, perform the labs, and complete the required readings; then, instead of a final exam, the writing students would submit a final portfolio, representative of what they’d learned through these studies.

|

The various animal shells, bones, teeth, and feathers displayed throughout this space remind me that Claudia’s approach to teaching (and to writing) was rooted in a relationship with—and insatiable desire to learn more about—the natural world.

|

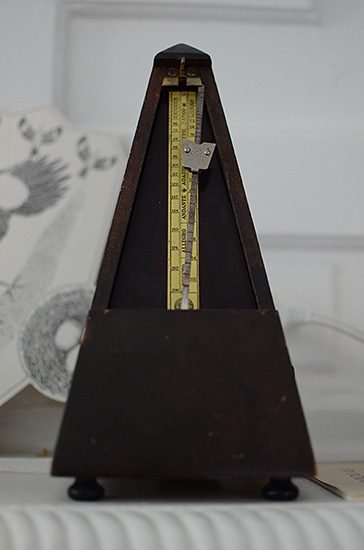

On the mantle, she also displayed a metronome, which she sometimes brought to class. She wanted to delve into conversations about prosody, but our schedule was packed; we didn’t have the time. So, Claudia found another way, and offered to facilitate a series of optional afternoon sessions in which we discussed rhythm and stresses, patterns, and feet. We practiced together here, scanning poems while she read them aloud, the metronome ticking along its cadence. ![]()

|