Introduction to Remember

|

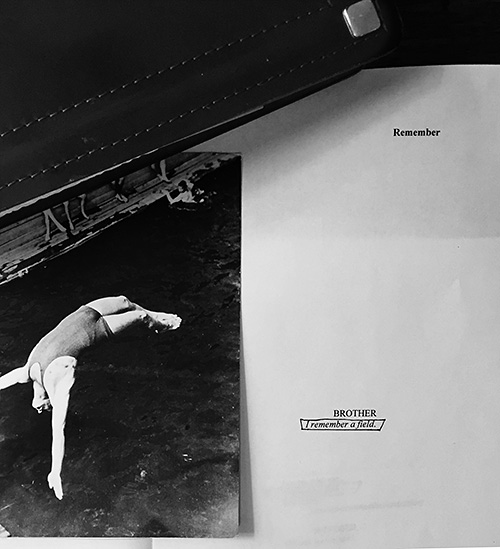

Liz Appel’s Remember is a play that may cause readers to wonder, on first reading, whether they’ve just had the full experience of this work—whether a performance was ever envisioned by the playwright, or would even be possible. Although the emotional arc is satisfying on a deep, intuitive level, it’s hard to walk away from this piece without questions. Important, stimulating questions, but questions nonetheless. Knowing this, Appel was gracious enough to correspond with Blackbird, to give readers further insight into her ambitious and enigmatic work.

On the most basic level, Remember depicts the deep, urgent desire of a pair of siblings, removed in time and space from their childhood together, to do just that—to remember. Brother is gone from the plane of reality—dead in some war—but Sister keeps hold of him on the plane of desire, on the plane of memory, on the stage. Appel suggests why it’s so hard for her to let him go:

For her, it’s about finding a kind of agreement—can they agree on a childhood memory (the need for their stories to match), and if so, could this lead to a greater sort of agreement or understanding, a way for her to hold on to more of him? Part of this is memory, and part of this is, I’m sure, a desire to confound time. Maybe that’s the conceit of the piece: if you want something badly enough, maybe you could bend the universe, just for a moment, to reach across chasms and touch things that are lost.

Appel pushes the dramatic form to its limit, crafting stage directions that make us, simply through reading them and envisioning the performance, question the physicality of a stage, the physicality of a body. Through our conversation with Appel, we’ve become convinced that just as Sister and Brother make a pact, so, too, might the actors and the audience:

To me, part of what makes the compact of the theater powerful is that of live bodies in shared space, the idea that when we attend a play, we all agree to share time and space, we all agree to age, to expire a little bit with each other. The critic Herbert Blau wrote that part of the power of the theater is that we are watching actors literally “dying before our eyes” . . . I think the same thing goes for the audience members as well—life, or death, isn’t just a spectacle, something that happens up there on stage—it’s what’s happening to all of us for the duration of the piece.

This is a play that invents itself as it goes along, managing to sharpen in focus and clarity the further it careens away from our expectations. The finale is at once monumentally ambitious in its abstraction and deeply personal in the way we intuit it. Appel hopes to bridge this gap:

| Isn’t this what good theater tries to do: deliver us into a strange world that is still somehow made recognizable, a world that may be totally other, and yet is still experienced as personal? At least that’s what I hope. And I figure that part of what’s underlying the piece is the drive for a greater kind of recognition: for the sister to recognize the loss of her brother, for her to recognize that lost things don’t get to come back except maybe through the images we have shored against our ruin. |

|||

| Isn’t this what good theater tries to do: deliver us into a strange world that is still somehow made recognizable? | |||

| Remember a one-act play |

Introduction

Remember