Unequivocal Painting: The Watercolors of Javier Tapia

We begin with a conversation in the studio of Javier Tapia, a Peruvian-born painter whose seemingly existential outlook defies categorization.

Life is pain interspersed with moments of release. If we embrace the pain, we may find joy. If we reject it, we will suffer without understanding. Either way, life ends in death. Should the realization invite suicide? No, unless the Gestapo knocks at the door and there is no escape. By the way, “What can paint do?”

“What can paint do?” It is a dangerous question, of course. The uninitiated could even see it as disingenuous, as if the artist were evading the act of painting or, worse, placing the burden of responsibility on the paint. In the case of Javier Tapia, both conclusions would be wrong. The question places the responsibility squarely on Tapia. Paint is his Sisyphean rock. He will push it upward only to have it fall down. He will push it again, and it will fall again. The process seems endless, and he could end it by moving out of the way. But he will not move any more than the rock will stop falling. The resulting tension is irrational. It is absurd. It is, above all, inevitable—at least to anyone who is willing to engage with the absurd, which is to say, with life.

For Tapia, painting is the avatar of that engagement.

|

|

| Javiar Tapia in his studio | Photo by Terry Brown |

Painting as subject, content, expression, and eternal question is the means by which Javier Tapia moves beyond the limits of language into the animal world of lived experience. Life is its own end. There is no need for salvation because there is nothing from which to be saved. There is no transcendence because there is nothing to transcend. There is nothing to vanquish and nothing to overcome except the fear of the encounter. There is only life, and the artist can either live it without preconceptions or expectations, or run from it in a futile attempt to avoid the inevitable. As Tapia notes in reference to Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus, suicide and inaction are poor choices. Life must be lived. The painter must paint soberly, without illusions about the world, his life, or his end. Such is the basis of a good life.

|

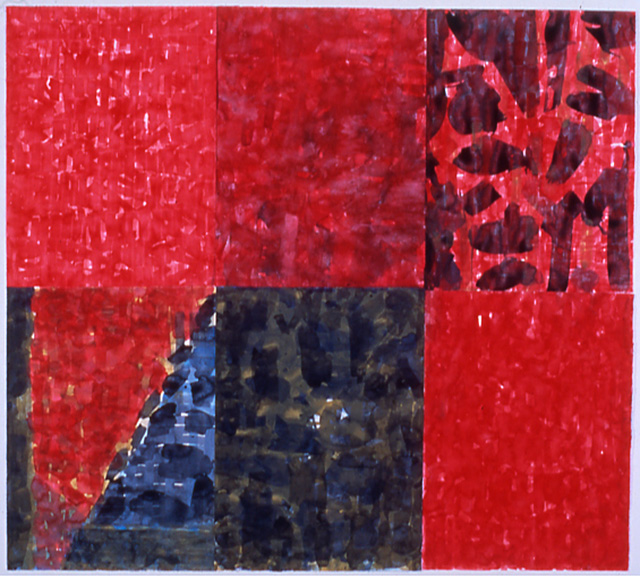

| Untitled, 2012 Watercolor on Arches paper 60 x 66 in. |

This leaves the will of the artist and his partnership with the paint and the substrate. Together they form a trio that confronts life with fully open eyes. Nothing is left unseen. Everything is discussed, parsed, mocked, embraced, rejected, and reembraced in a dance of endless questions. To find an answer is to kill the dance. With every step there is a game with pain and pleasure, suffering and happiness. There is violence and compassion. The music is melodic and discordant by turns. The rhythms alter between jagged syncopations and waltz-like smoothness. Occasionally, one of the partners will step on the toes of another. The action is deliberate, like a Zen master who whacks a sleeping acolyte with a bamboo rod. The paint will not let the painter sleep. The paper defies them both, but they revere it nonetheless. Love is too much to ask. The process is called watercolor. It is unforgiving. It has no choice. That is its nature.

|

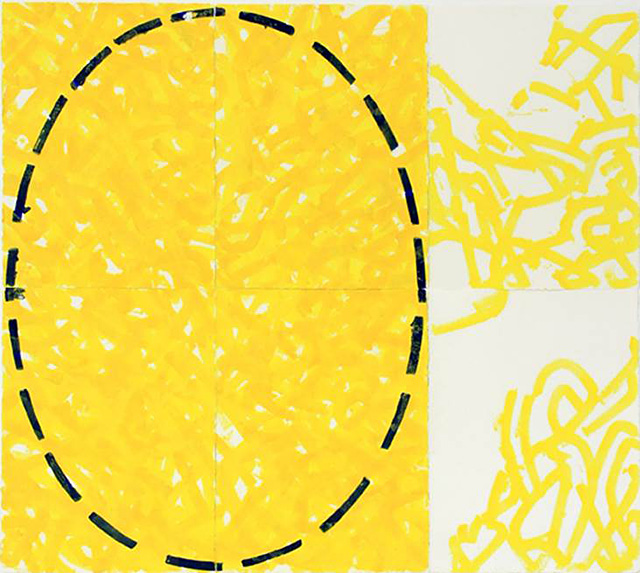

| Untitled, 2013 Watercolor on Arches paper 60 x 66 in. |

Watercolor is often treated as the stuff of children, amateurs, and gifted English gentlemen who read Wordsworth and paint the Lake District with romantic melancholy and classical skill. Rightly or wrongly, those are the clichés that surround the medium. It is true, of course, that within the Western tradition the English and their American cousins have had more than their share of watercolor masters. Yet the medium has seldom gone into the realm of nonrepresentational high art with the same seriousness and power as oils and, more recently, acrylics. Aside from Chuck Close and John Cage, few modern painters have addressed watercolor in a manner that could challenge oils.

There are solid physical reasons for the avoidance of watercolor in large-format pieces. The paper is difficult to handle in large sizes. The finished pieces must be shown under glass. The frames are heavy, expensive, and difficult to transport. Furthermore, the paint itself is unpredictable. For one thing, it is transparent. Its appearance changes as it dries, and, unlike oils and acrylics, it does not sit on the surface of the substrate: it penetrates the fibers of the paper. A watercolor layer cannot hide the one beneath it, but adds to it instead. Under the circumstances, commitment is essential. A change of heart requires either scraping off the paint, and the paper it stains, or washing the painting with a hose. Such physical issues are enough to deter many would-be watercolorists. Tapia accepts them as a challenge.

|

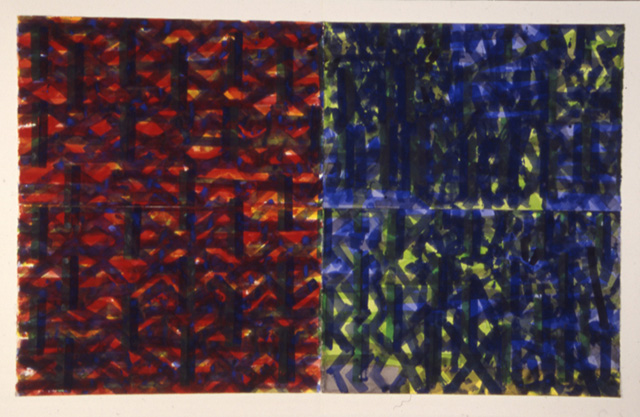

| Untitled, 2013 Watercolor on Arches paper 52 x 82 in. |

To paint is to be right and wrong by turns. Neither must win. Each change, each reevaluation, brings new insights. The insights are the reward, and they tend to be ephemeral. The process must continue, but not toward an end—no, only toward more reevaluations. Each color changes the whole. One stroke alters days, weeks, and months of work. Is it a failure? Does it matter? It matters only insofar as the process produces new insights. The truth remains elusive. That is the act of painting. Tapia knows it intimately. It is a material encounter. It is a physical engagement that cannot be reduced to an antiseptic exercise in thought. Painting is concrete. Nonrepresentational painting is especially concrete as a nonmimetic entity with its own independent reality and voice. Free from the burden of imitation and narrative, nonrepresentational painting assumes a higher freedom and responsibility. Abstraction, as the public often calls it, exists as both concept and reality. Above all, it is the total truth of paint as a material existence that defies and even defeats the ego-driven quest for the ideal. In fact, there is no need for the ideal, except for those who close their eyes.

|

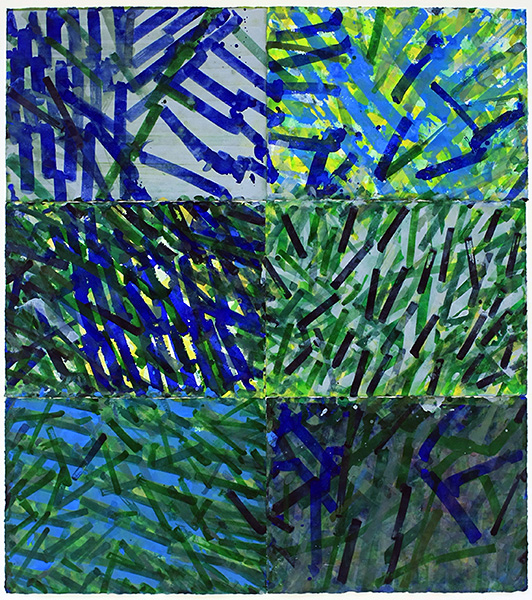

| On the Road to Mount San Victoire, 2014 Watercolor on Arches paper 60 x 66 in. |

Tapia’s open-ended questions should not be mistaken for negations or evasions. Distrust of an absolute is not an endorsement of inaction in the face of necessity. Nor does the absence of an ideal imply contentment with restful mediocrity. On the contrary, the call to action defines both life and art. Both rise to the heroic when they act as affirmations of existence rather than aspirations to what can never be. Within that reality, nothing can happen in a watercolor painting that defies natural law. If watercolors are understood in terms of delicate transparency, then Tapia makes them dense to the point of opacity. The defiance of tradition does not violate the mechanics of the paint. The medium asserts its physicality and compels the viewer to reconsider preconceptions and expectations. Density, opacity, and a uranium-like heaviness defy the clichés with self-aware intention and laughter. Still, the heaviness is not heavy-handed. The touch is masterful. The paint is not forced but cajoled into opacity. The weight comes from the paint, not from the painter’s hand.

|

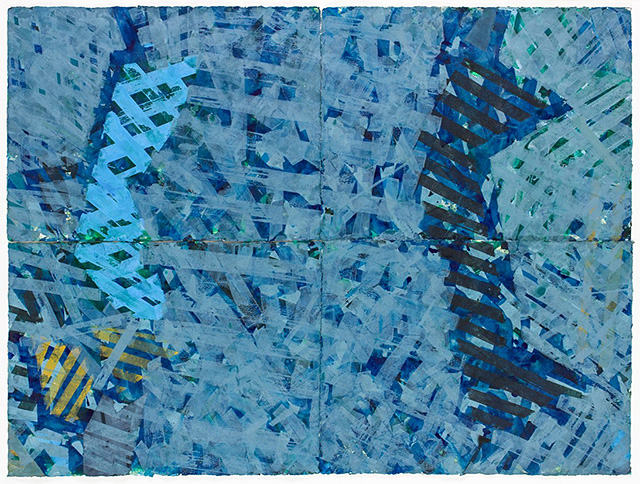

| With the Wrong We See, 2016 Watercolor on Arches paper 61 x 45 in. |

A 2016 painting titled With the Wrong We See alludes to the contradictions that Tapia invites and cultivates. The painting consist of four vertical sheets of paper, two in mostly pale blue and blue-green respectively, and two in dark, chromatic gray and black. The initial effect suggests a variegated checkerboard. It is misleading. Even without the title, it soon becomes clear that “with the wrong, we” do indeed “see.” For one thing, the checkerboard is broken by a wedge-like shape that cuts from the upper-right rectangle into the one on the upper left. The effect is subtle but disruptive. It suggests a determined denial of design: not entirely an accident, but not a predetermined gesture. The resulting tension augments the conflict between dark and light as well as the civil war between two closely related yet different hues. Blue is not blue-green. The difference is irreconcilable. Nor is the hand an obvious mark-making instrument when the struggle between transparency and opacity gives a mechanical impression that negates its maker. Of course, the maker is very much a man, and his hands made the painting, but the nearly industrial weight of the dark passages suggests a shift in power from the man to his creation. The hint is especially ominous in light of contemporary developments. Blue and blue-green cannot compete with the forces around them. What exactly do we see with the wrong? Do we even wish to know? The painting will only speak through its plastic tension. It seduces and repels—like a mirror.

|

| The Great Intruder, 2016 Watercolor on Arches paper 40 x 66 in. |

The Great Intruder asks a different set of questions. It too asserts a will to contradictions, and its horizontality defies expectations; but who is the intruder? At this point it is important to revisit a forgotten discourse. A nonrepresentational painting composed of fifty-five paper rectangles recalls the modernist grid. Yet, in this case, the grid is a red herring. It serves a purpose contrary to the marks. In fact, it opposes the marks. They, in turn, deny the possibility of a true allover composition. Some parts are more important than others. Some have more weight or act more assertively. Diagonals and curves mock the grid. To the right of the middle, near the top, orange strokes emerge from the whiteness and break through pale blue-gray and green with dissonant aggression. Competing contradictions fight for the viewer’s eye. Even the white of the paper refuses to act as a ground and emerges as pure light. The painting moves in every direction including from the back to the front and to the back again. The painting is alive, but life devours life. Modernism understood the death of God and could accept the consequences. It could survive without parental intrusions.

|

| The Gap, 2016 Watercolor on Arches paper 40 x 66 in. |

With or without God, modernism retained its dignity and manners. Even the Dadaists could not betray the canon against which they attempted to rebel. Like the aristocrats who collected their work, the modernists, including a later generation of American rebels, could not abandon centuries of tradition. As Tapia says, “We all have parents.” The attempt to hide a genetic lineage was doomed. Pollock was too elegant to be a patricide.

The beauty of elegance often belies its awareness of cruelty. A slight bow of the head, long silk gloves, the right perfume, and the exquisite politeness of the well-bred reflect an intimacy with tragedy that guillotines cannot intimidate. Elegance, like refinement, is currently out of favor because it demands a willingness to suffer silently outside the public eye. Elegance lacks authenticity,or so it would seem. It is easy to forget that all too often authenticity is little more than vulgarity aspiring to respectability. Elegance, on the other hand, speaks to a deeper understanding, to the completeness of a life that smiles at pain and bows its head, if only slightly, like a gentleman from the ancien régime who has the dignity and grace to forgive his executioner. The Gap does not pretend to address those qualities. Instead, it embodies them, however unselfconsciously. Once again, an incidental grid defies an antigeometric struggle. Two dominant shapes confront one another across a chasm of gestural activity that threatens to overwhelm them. One shape is dark yet oddly passive whereas its lighter, more colorful opponent possesses a venomous quality. Of course, such a suggested narrative is false. Nonpresentational paintings do not illustrate stories. There is no duel in The Gap. But there is a struggle that suggests something tragic and compelling precisely because it can never be shown, illustrated, or known—something that can only be experienced and felt in quiet privacy. That something is discreet, unlike a parvenu.

Javier Tapia is an unequivocal painter. His questions are open ended, but his paintings are concrete and complete. His forms struggle with the truth of their existence without dissembling or asking for mercy. They are fully themselves on a surface that holds them with its gravity and tries to swallow them into the anticolor of its fibers. The forms, like their maker, resist their gravitational prison and assert themselves against the odds. The resulting dialectic will never be resolved. There will be no synthesis. Hegel will be denied his contrived due. Art triumphs over idealism and teleology. The painter smiles and continues the struggle. He knows it is absurd, but he will push the rock without self-pity or regret. ![]()

Javier Tapia is a Peruvian-born artist, whose work is included in the collections of The National Museum of Peru, The Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, and The Museum Pedro de Osma in Lima, Peru. He is an Associate Professor of painting and drawing in the Department of Painting and Printmaking at Virginia Commonwealth University.