VMFA Artist Talk: LeRoy Henderson

On February 16, 2017, Richmond-born New York photographer LeRoy Henderson was in conversation at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts with Sarah Eckhardt, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art. Henderson’s work is among recent acquistions to the museum’s collection. Alex Nyerges, Director of the VMFA, introduced the event. “Our goal,” Nyerges said, “is to have the best collection of civil rights photography in the world and we’re well on the way to that; our goal is to have the best collection of photography by African American photographers on the planet.”

Nyerges briefly touches on Henderson’s formative years in Richmond, Virginia, the photographer’s purchase of a Brownie Hawkeye camera at the age of thirteen, and his eventual move to New York. Nyrges go on to say, “I put him in the category of . . . Edward Weston—people like Walker Evans, Ansel Adams, photographers that have had an impact on photography and the world of art in the twentieth century.” Nyerges adds "Henderson is, as I say, almost unparalleled in the field but not getting the recognition to this point that he deserves. As his home town institution, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is going to help correct that."

|

| LeRoy Henderson & Sarah Eckhardt Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 16 February, 2017 |

Sarah Eckhardt: LeRoy, I am so thrilled to have you here on stage. It is a privilege to have you here. We met when we acquired your work for the Signs of Protest exhibition, which was up in 2014, and you had a work at the same time in Deborah Willis’ Posing Beauty exhibition. I think that was your Stokely Carmichael photograph.

LeRoy Henderson: Exactly.

SE: So you had two photographs up at once, and you came down to visit, and you brought your sisters with you. So there are two reasons I’m excited about tonight. One is—every time I have talked to you about your photographs you tell an amazing story, and I thought we needed to share these stories because they were building up and building up. And the second reason was because your sister said she was so happy to have you home and she’d love another reason to have you home, and I felt like I wanted to fulfill that request. So we’re glad to have you back in Richmond, which is why we were going to start tonight talking a little bit about your Richmond roots.

You have a lot of friends out here, but do you want to just give us a little bit of your overview of where you grew up, where you went to school?

|

| Google Map rendering of current boundaries for Richmond’s Washington Park neighborhood. |

LH: I grew up in Washington Park; there are people here who know that place.

AUDIENCE: Yeah.

LH: Washington Park—went to a school in the neighborhood called Washington Park Elementary. My mother got me out of there by the time I was ready to go to junior high—sixth grade—and got me into Booker T. Washington downtown on Leigh Street, and that was the best thing she could have done because my mother was progressive; she didn’t take prisoners. She was about making opportunities for us. I went to Booker T., and the reason we left Washington Park was because we had—that was a nice neighborhood school—some classes had two grades in the same classroom, but my mother wanted better than that for me.

So I went to Booker T., tried to die. Didn’t want to go, would ride my bicycle from Washington Park downtown to Booker T. on my way to school, but the closer I got the more I cried. Got there and loved it. There were some boys in the neighborhood—two boys, two brothers—who were going to Booker T. They were taking art classes; I’d never even heard of it. I found out about it—my mother had gotten me into Booker T. by then—and I wanted to take art classes. I took it on myself at thirteen to look up the teacher’s name who was the art teacher at Booker T. in the phone book, Mrs. Gray. Thirteen! Called Mrs. Gray and told her I wanted to be in her class. She said, “Oh, you’re welcome if they let you change your class.” And fortunately, the principal, Mr. Booker, was a friend of my family. One day in social studies class in the afternoon, Mr. Booker comes up to my class; Mrs. Harris protested when he came to take me out of there. She said, “He’s got to take this!” He said, “Don’t worry, I’ll take care of it.” Took me down to Mrs. Gray, to the art class, and I was in hog heaven. Let me tell you, that was my very first experience of actual art classes.

|

“The army—believe it or not—they let me carry my camera in basic training, taking pictures of stuff, like when we were training with our rifles or taking them apart, or out on the field maneuvers . . . ” |

From there I went to Maggie Walker, and I had an art teacher there who was another inspiration, Mrs. Coleman. And let me tell you, that lady, she inspired us so; and we just had a wonderful time in Mrs. Coleman’s classes. She had tried to introduce us to different artists. I’ll never forget the day she showed us a Van Gogh piece. Some of you have seen that picture with the swirling sun and stars and whatever in the sky. She said, in these exact words, “This picture was taken by a crazy man.” I didn’t know what she meant, but that’s the way she described it. So, you know, that was the art background.

First of all, my parents never discouraged me. And one other thing about photography, I wasn’t much into photography, but I did see my grandmother had a stereoscopic viewer, and some of you here might know what that is. It’s a device where you put this card in front of the viewing lenses, and there’s two images. When you look through that thing, it’s in three dimensions, and that was fascinating to me. Plus, my grandmother and my mom used to bring home magazines—Life magazines—from homes that they worked in for people. I used to pore over those things. So somewhere along the way I decided to buy a camera, but before I bought this camera, this whole phenomenon of what lenses or things could do, I discovered with a magnifying glass. At the end of the hall of the house I grew up in, I found out if I held the magnifying glass a certain distance from the wall, I was able to pick up the image of the front door with it—glass door—and that was fascinating to me. It was like seeing what you were seeing in a camera ground glass as you look through it.

|

| “Ground glass” is a translucent panel at the back of a bellows camera on which the photographer focuses the inverted image rendered by the lens. (Think of old movies with the photographer doing something mysterious under a fabric hood behind the camera.) The illustration above shows generally the principal that Henderson discovers as a young man with his magnifying glass. In a camera, figure B above is in the position of the ground glass. |

But anyway, moving to the purchase of my camera. At thirteen I bought myself that Brownie Hawkeye that Alex Nyerges mentioned to you. Bought that thing, wanted to replicate what I saw in newspapers. Like the Richmond News Leader, which no longer exists, used to run a contest once a year. I used to look at those pictures and want to be like that. Then eventually I transitioned from the Brownie Hawkeye to another, more impressive camera. I was so proud of myself. That little camera had a bellows—it was a bellows camera that opened up—and had that impressive bellows with the lens on the end. I was so proud of that thing; I’d set it on top of the piano and just look at it. I mean it was just fascinating to me. But that’s as far as my interest in photography went.

I continued to pursue my art and went on to Virginia State, majored in art ed, had to take all these kinds of art classes that you would be teaching, and did my practice teaching and art. By the way, when I was growing up in Richmond, I hate to tell you, I was so bored. I was bored out of my mind. Couldn’t wait to get out of Richmond. Went off to Virginia State—didn’t go far—but that was far enough, because that was a really incredible experience for me: going off to college, going off to Virginia State, and majoring in art. One of my classmates is here.

Miss Meredith was the chairman of the art department. We had Miss Meredith, we had a watercolor teacher, we had a ceramic teacher. I’ll never forget, Mr. Kersey was the very first teacher that literally introduced us to drawing from the nude in class, of all things! And there was no looking back from there. So I finished Virginia State—and we did jewelry making out of silver, we did things out of copper, we did printmaking, we did ceramics, and all of those things that we had to do to teach. I finished Virginia State, went off and did my practice teaching, got out of the school, finished, went off to the army. I still wasn’t into photography a lot, but I had a camera, so I could use that camera to take a few photographs.

The one thing I did with that camera when I went off to the army—believe it or not—they let me carry my camera in basic training, taking pictures of stuff, like when we were training with our rifles or taking them apart, or out on the field maneuvers, when we were getting our food served to us. And they let me carry the camera, which surprised me, but they did it, and that was very unusual, because we had a very progressive first sergeant.

|

“I remember we would have our critiques, and I laid my work out among the other students’—this guy walked around and he would invariably turn every one of my photos over, face down. That was a rejection of my work.” |

So that’s the end of the photography for a while. Went into the army and was assigned to Europe, and was still interested in drawing. I did learn to process film in a service club over there. I took a few photographs; it wasn’t a big thing. But I went on and continued drawing. I even did some drawing on location. I remember I have a drawing—now I never finished it—in pastel, a drawing I did in Amsterdam, one of those streets where you see the bridge and the canal running under and those beautiful homes and buildings and all. So those are things I was still pursuing in art. I took a boat trip up the Rhine River and stopped in little towns and took a few photographs. One of my photographs I took on the Rhine River trip was the Cologne Cathedral, a magnificent place. I remember taking a picture of a bridge leading over the river to the Cologne Cathedral, where you could see it in the background. So those kinds of things, I did that, but still wasn’t doing much with photography. I’m trying to think now; from then on I did take a few photos, but when I got back to the States I decided I was going to go back to school. I wanted to go to grad school.

I went to grad school and majored in Fine Arts Ed, and went to Pratt Institute. I remember when I was thinking about abandoning art for photography I had a conversation with my daddy. I told him I thought I was abandoning my art training. Can you imagine that? Not realizing the connection? But it made all the difference in the world, because ultimately, when I taught a few photography classes, one thing I would tell students was to look at art as well as photography. I was inspired by—I began to become aware of Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange with those Dust Bowl photos, and Walker Evans, and just people on that level. I started to become aware.

While teaching in the New York City school system, I decided, “this is not what I want to do.” So I left the teaching and started freelancing. I even took a course at the School of Visual Arts called Photojournalism and Human Values. I remember that class. The teacher—I remember we would have our critiques, and I laid my work out among the other students’—this guy walked around and he would invariably turn every one of my photos over, face down. That was a rejection of my work. Matter of fact, when I went to take that course, he looked at the portfolio I had, which had a lot of color stuff, and he said to me, “You wouldn’t make a good photojournalist. Maybe you’d make a good advertisement photographer.” I said, “I want to take the course anyway.”

So I went on and I pursued it, and in the course of taking that photojournalism class I had to find a subject for an assignment. That’s when I found those pictures of Dorothy Pitman Hughes and Gloria Steinem, who were involved in the Day Care movement. I mean, really, that was serious. That’s one of the things that really got me started in seriously pursuing documenting stuff.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Portrait of a Woman, Charlottesville, VA, 1967 |

LH: This is in Virginia.

SE: Yeah, so we started with the Virginia photographs, and we’ve got Virginia, and then some people, and we go kind of roughly chronological. But it’s interesting that you’re talking about Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, because these early photographs, the earliest ones that we have . . .

LH: . . . pictures of what—Americana, in a way, ordinary people in America. That lady you just saw, that was along Route 33. They were picking salad. I drove by, stopped and saw them, took it on myself to get out the car and go over there and ask them if I could take some pictures. This man who was with her, he said, “Sure, take all the pictures you want!” And so I did. The next picture was on Route 33 also.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson The Jackson Family, along Route 33, west of Richmond, 1968 |

LH: Route 33, heading west towards Ruckersville, through Louisa County. This was a family I saw along the way, the Jackson family, and I stopped and talked with them. I just thought this was magnificent, this lady in her matronly, powerful way, standing there with her little munchkins. That was one of my favorite shots. By the way, this is in the collection here; this is one of the pictures the museum has acquired for their permanent collection.

SE: Yes.

LH: That’s one of them.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Dining Car, 1967 |

LH: I was on assignment to get photographs of service workers. I was on the train going down to somewhere in southeastern Virginia. I was in the dining car, and that was one of the pictures I saw that I thought would fit into my theme very well. It was during the Civil Rights movement, and this film company wanted to do this story about black service workers, mostly, and that was one of the pictures I saw and captured. That was on Amtrak.

SE: In Virginia.

LH: Yeah, heading down—heading south. I went down into the Norfolk-Portsmouth-Hampton area, and got some more pictures. Matter of fact, I almost got run out of there because I was with a bunch of people out there, and there was a white farmer with his vegetable truck, and he got suspicious. One of the guys said to me, “We got to get out of here.” So I left that scene, but that was part of that series on service workers.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Boy with Flag, 1989 |

LH: That picture, there, my family here would recognize that. That’s my cousin Gary Johnson’s son. Gary was killed in a car accident on his way to his brother’s wedding. At that funeral, I didn’t pose that. I didn’t set that up. That little boy, his son, was standing there, and naturally my instincts said this is the kind of thing you respond to, you don’t even have to think about it. That’s in several collections. This is in the collection here at the museum now. I think the first museum that bought it was the Brooklyn Museum. I think here is the only other place that I know it to be.

SE: And it’s in Deborah Willis’s book.

LH: And it’s in Deborah Willis’s book, Reflections in Black. Someone here who works at the museum, Paula, asked me to sign her copy with that image in it.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Reverend McIntosh, pastor of Bethel Baptist Church, with his wife, at “Big Meeting Sunday,” 1989 |

LH: That’s at a “big meeting.” Now, how many of you know what a “big meeting” is?

AUDIENCE: [Murmers and approving light laughter.]

AUDIENCE: Been on the ground . . .

LH: All right, okay. This is a “big meeting.” People go back to their home church once a year in August—usually it’s the second Sunday in August—and this was at Bethel Baptist Church in Unionville, Virginia, near the Chancellorsville Civil Rights Monument.

This is the pastor and his wife, Reverend and Mrs. McIntosh. Now, as old-fashioned as they look, they’re really young people. But look at that lady, look at that dress. I mean it looks like something back out of the ’30s. This was ’90-something! But they posed for me and I just love that photograph, because it actually was reminiscent of another famous picture that I don’t know if I should mention, but anyway.

SE: Well, actually, I’ll just mention that quick connection we made. When you described “big meeting” to me, it reminded me of Edna Lewis’s description, in her cookbook, of big meetings, and it turns out that this is actually . . .

LH: At her church. Sarah is referring to Edna Lewis, who is a renowned culinary specialist. I found out about her in an article in the New York Times. I found her; I even went to photograph her. She worked at a historical restaurant in downtown Brooklyn called Gage and Tollner. Gage and Tollner had been there since the 1800s, and Edna Lewis was the cook there. I took pictures of her there, but I also got to know other family members. That’s how I ended up at her church in Unionville . . .

SE: I can’t believe that connection.

LH: . . . because that’s where she’s from.

SE: Yeah.

LH: That’s where she’s from, and that’s the church. And that church, by the way, is over a hundred years old. That’s the original church. And as you know—the big meetings—they’d have church in the morning, they’d break for food, and then they’d go back to church.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Girl at Bethel Baptist Church "Big Meeting," 1989 |

LH: That’s where that little girl—she came walking by with her plate of food on top of her bible and hymnal. I couldn’t resist that picture, that little girl with her little pearls and her little flowered dress and her little socks and patent leather shoes. I mean, it was the perfect setup!

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Douglas Wilder's Inauguration, 1990 |

SE: So this is our final Virginia image.

LH: Oh yeah, Doug Wilder’s inauguration. I attended that. I managed to get the credentials from a magazine called Emerge—doesn’t exist anymore—but I was able to get that, and I went to all of the events related to that inauguration. I went to the party at the Jefferson Hotel the night before, I went to the ball afterwards. I think I took my sister, and I took some of my family along. They tagged along. Nobody denied us. It was amazing to be there, and that was, like you mentioned, a transitional time. This was a black governor of Virginia, of all places. I mean, that’s no small matter as we all know. But that was in the ’80s—late ’80s, early ’90s. You know, but that just shows—there again—that’s an example of the progress we’ve made, in spite of how much more work we need to do. That’s just a fact.

SE: So we had a few images you wanted to talk just a little bit about. We have a lot of historical documents, protest images; we wanted to show that you see other things at other times.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, NY, 1994 |

LH: Yeah, in my art background I look for beautiful compositions. This was in the Brooklyn Botanical Garden on a foggy day, as you can see the fog in there. I said, “I don’t know if they’ll like me putting this in with all that social commentary stuff,” but I said, “I’m going to put it in there. ”

SE: Yeah, it’s great. Here’s another one from the Botanical Gardens.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, NY, 1994 |

LH: That’s in the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens; I lived across the street from it. Of course, you can imagine, that’s not a one-shot. I had to shoot—you have to hang around to get pictures like this. You have to hang around and be willing to do a lot of waiting as a photographer. You wait a lot. And fortunately my timing was good on that.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson O'Henry's, Greenwich Village, NY, 1960s |

LH: To me that’s just a still life. It’s reminiscent of some of the stuff I’ve seen by people like we’ve mentioned, like Walker Evans, or whoever—any of these people that inspire me. This is just a still life of a restaurant in Greenwich Village, and I just passed by and I saw that setup. It was a perfect setup for me, like a still life. I just love the contrast between the light and the dark and the fact that you can see the name of the place. It was just a moment. That’s all. That’s why I put those three pieces in there.

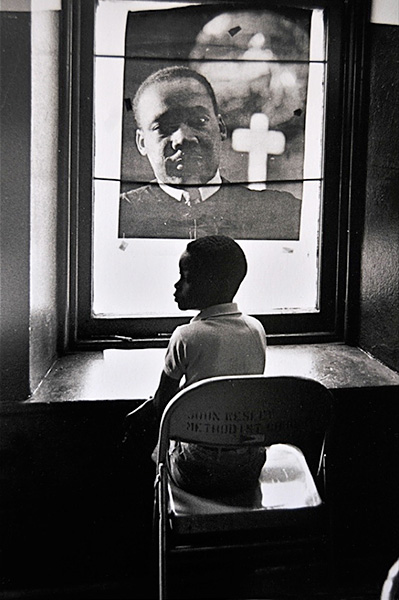

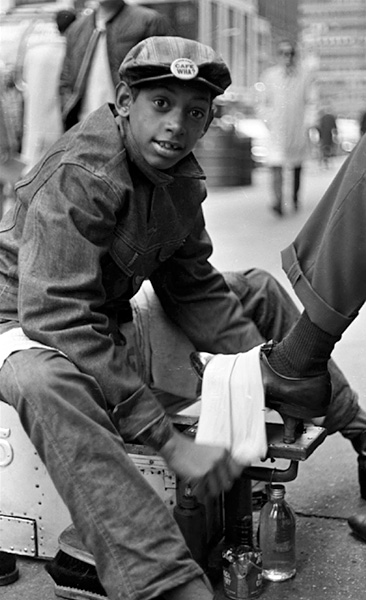

SE: That’s great. I think you have such a talent with photographing children, and so we have a number of your images of children before we get to some of the protest images.

|

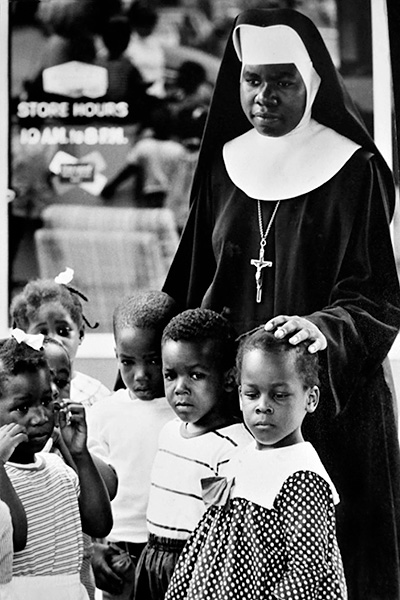

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Children outside of Catholic Orphanage in Landstuhl, Germany, 1959-1961 |

LH: Those kids in that group photo, that was in Landstuhl, Germany, at an orphanage. These are kids who were fathered by GIs, who fathered them and went back home and left the mothers with them.

SE: Wow.

LH: That was very commonplace, very commonplace.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Summer Day Camp, NY, 1965 |

LH: This was in a summer job I had working in a summer day camp. This little boy happened to be sitting—I mean, I couldn’t have created a better setup. I couldn’t have even done that better than what you see there. I came up the steps in this church where we were, and there that little boy was. I didn’t even have my camera in my hand. I ran into the little office and grabbed the camera, and I think I got one shot. I thought it was symbolic because of King and the child.

SE: It’s a window, and then the poster’s over the window? And that’s why it’s glowing?

LH: Yeah, the poster’s over the window, and that’s just a little alcove where he was working, drawing or something, you know.

SE: It’s beautiful.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Storefront Church, NY, 1977 |

LH: I was working on a film. This was in a storefront church in Brooklyn. I took a camera crew in there, doing a job for Dutch television. I didn’t have anything to do because I brought the crew in and they were busy shooting. I had my camera with me, and I always take advantage of it. I just looked around to see if I could see any images I wanted to capture. I was sitting right across the aisle from them when I saw that, and to me that just registered. That lady in the middle—I eventually showed that out in an exhibit in Long Island and there was a guy that told me the lady in the middle was his aunt. It’s amazing how you connect.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Shoeshine Boy, Times Square, NY, 1965 |

LH: This shoeshine boy, Times Square, my very first photo assignment. Shoeshine Boy in Times Square, and I just put that one because it was more in-your-face. You can see what he’s doing, didn’t have to explain it.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Brooklyn, NY, 1965 |

LH: This is East New York, Brooklyn. I was walking around. Those little kids saw me. I saw them, and I grabbed that picture. But to me it wouldn’t be the same without that cannon there. I’m sorry, but that toy cannon, if you let your imagination go a little further, you can take the things that that’s a metaphor for. You know, being under—we are under threat all the time.

|

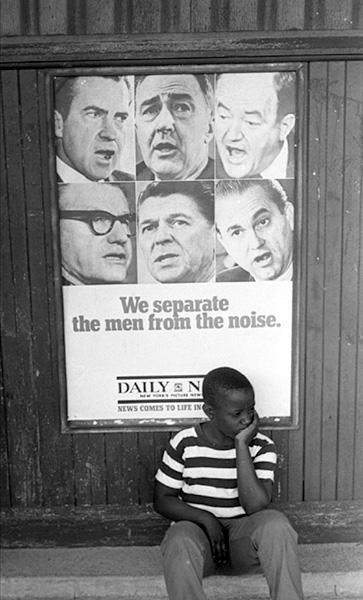

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Subway Platform, NY, 1965 |

SE: This is another incredible contrast.

LH: Yeah, during the political campaign. This was a little boy who was sitting down in front of that poster, bunch of kids that I accompanied to a summer camp outing. And in fact, there’s Nixon, McCarthy, Hubert Humphrey, Nelson Rockefeller, Ronald Reagan, and George Wallace. This was a Daily News poster, but I couldn’t have set that up—I couldn’t have imagined that better than that. That’s why I was fortunate. That’s part of this whole thing of looking for stuff; you’ve got to be out there looking for stuff. You just have to be ready for the moment, like this moment: Coney Island.

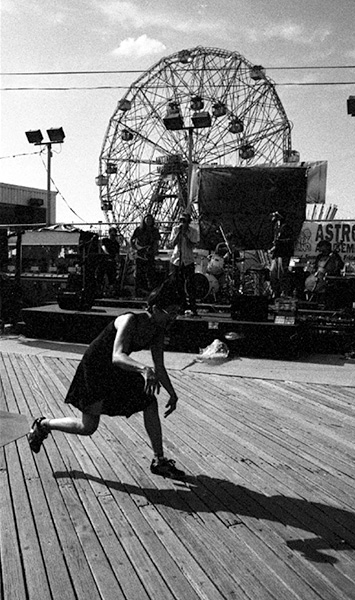

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Coney Island, NY, 1960s |

LH: I don’t know what that person was doing, but it was a very fortunate setup. It’s crazy; it’s kind of spooky, really. Matter of fact, I’d like to refer to that piece: I think about people that have inspired me—Henri Cartier-Bresson, he coined the phrase, “the decisive moment”—and I felt like that was really like a fleeting, decisive moment. I give credit for the inspiration here, you know.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Street Troupe, NY, 1970s |

SE: Now this one, if people go upstairs—we’ve just opened an exhibition titled Black Photographer’s Annual to Commitment to the Community, which is a quote from Toni Morrison’s introduction, and that was an annual in 1973—

LH: Right—

SE: Put together—

LH: Joe Crawford put that book together. Right.

SE: And then also working with Louis Draper, one of the picture editors, Beauford Smith—

LH: Louis Draper, exactly. Louis Draper was involved. This was a traveling troupe who would go around the city doing performances in the street, sponsored by the city. I just love that quiet moment I caught there of the two of them, and trying to stay positive, but I still—somehow I can’t help seeing some other symbolism in there, pardon me.

SE: So tell me. Elaborate.

LH: Well—there’s this black woman, standing back, almost in a passive mood, and there’s this white guy standing there with his hat—his cap, you know—and that’s a stretch, that’s a stretch, but I can’t help but going there. Doesn’t mean that I was right because I’m sure they were very fine—compatible—enjoyed working together. There was none of that stuff that I want to allude to.

SE: This was the one that was reproduced in the Black Photographers Annual, so that’s on display upstairs in the annual.

LH: The book is open to that page.

SE: Right.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Family walking through Central Park, NY, 1973 |

LH: Okay. All right. Central Park in the ’70s, ’73 maybe. I mean, come on, walking with your kids—why is this little girl buck naked but got a purse on her shoulder and socks and patent leather shoes? And, by the way, nobody here will probably remember hot pants. Mom’s wearing hot pants, okay?

SE: And Dad doesn’t have a shirt on.

LH: There you go.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson 1973–1974 |

LH: My two boys. My two boys, looking at the butterfly. Not much I can say about that except what it is.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Concord Baptist Church, Brooklyn, NY, 1970s |

LH: That’s at Concord Baptist Church, my church. I just saw that lady with the little boy and I couldn’t resist.

SE: That’s such a beautiful balance, with the hats.

LH: Couldn’t resist. That kid’s expression says it all.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Imperial Biker’s Block Party, NY, 1980s |

LH: These young women are at an annual motorcycle biker’s club picnic.

SE: Let’s show that this is the . . .

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Imperial Biker’s Block Party, NY, 1980s |

LH: That’s another image from the same day.

SE: . . . Same day. So they’re at the same [event]. I love that contrast with the babies.

LH: Oh yeah, oh yeah, oh yeah, I mean, this series: young mothers, young women. And then to me, I just love the contrast, the silhouette, and the smoke from the motorcycles burning rubber and all that carrying on out there. And why is he wearing a sombrero and carrying one, I don’t know. I don’t even know. But it worked for me visually; it really worked for me visually.

|

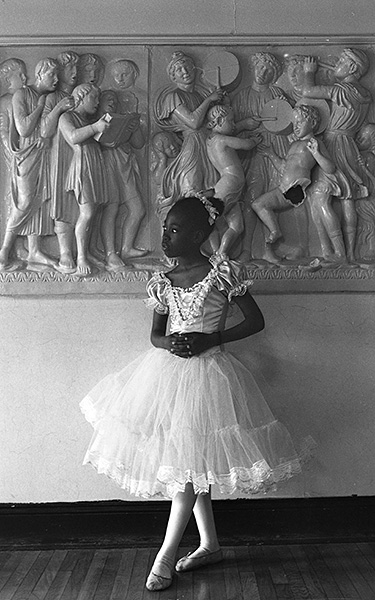

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Brooklyn Music School Dance Recital, 1994 |

28:00

LH: There’s my black ballerina. That has been a good photograph for my life. That little girl was standing there waiting to go on; there was a dance recital of kids. This was far off from her. I was sitting there with a backdrop. I was photographing every kid in front of a color backdrop who was in the recital. And her mom had just dressed her, and she was standing there in front of that barre relief, waiting for her turn. And that’s not posed. But I have to tell you this: Arthur Mitchell, who has the Dance Theatre of Harlem, I showed him that. This guy started picking it apart about the way her feet were positioned. A dancer, I mean, I just thought, “Why did I bother?” He made me feel like I had failed. But that picture, let me tell you, it’s in several private collections—I don’t think you have it here yet—but anyway, several private collections. I sold it through Phillips Auction House in New York, which is a major auction house. June Kelly Gallery sold it to a lot of people. My very first show, I think I sold about a dozen copies of that. It was a limited edition of a certain size at that time, and I sold all of those. And I later did another limited edition of about five or six and sold some of those, but people love that. Even Oprah Winfrey bought one. What she did, she saw it at an expo that the art dealers show up and have every year—the Art Dealers Association of America—and June Kelly Gallery had it in their booth, and Oprah saw it and bought it. But guess what she did? She asked for her ten percent discount. What can you do?

SE: That’s good. On that note, we’ll transition.

LH: Okay, back to the more social conscious stuff!

SE: Yeah.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Reverend Ralph David Abernathy speaking in Central Park, NY, 1968 |

LH: Ralph David Abernathy, many of you might know. That’s a flag of Martin Luther King in the background. That’s 1968, leading up to the Poor People’s Rally and Solidarity Day in Washington. This is him speaking in Central Park in New York.

SE: And tell me a little bit about how you decided—how did you become involved with the Poor People’s Campaign.

LH: I attached myself to the New York contingent. The guy who was the head of that was named Cornelius “Cornbread” Givens. I got my credentials to go down to Washington for the upcoming Solidarity Day. Because of that, I was able to go down, to have access, to be roaming around that place with my camera catching pictures like this.

|

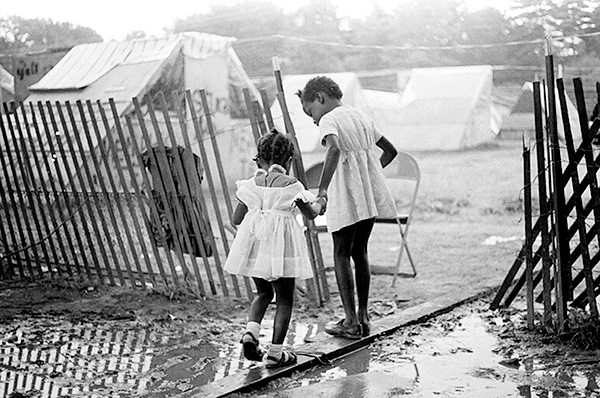

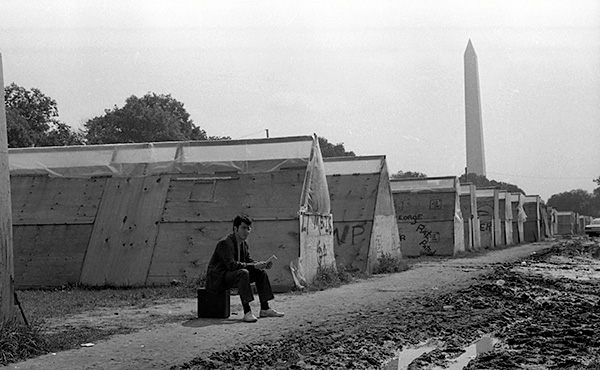

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Resurrection City at the Poor People's Campaign, 1968 |

LH: And let me say something about this picture. Those of us from the South know that at the end of a day after playing and getting all dirty, our parents would clean us off and dress us up. They continued that tradition in the midst of that muddy quagmire! Look at that little girl. Her mother—they were living in these shantytown—these little shanties that they’d built out of plywood and plastic—and dressed her up, and there she is.

|

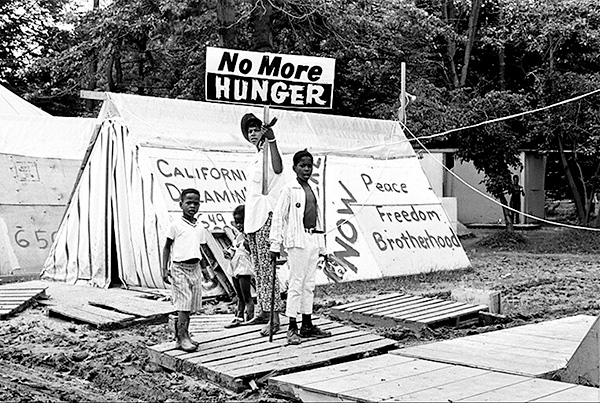

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Resurrection City at the Poor People's Campaign, 1968 |

LH: And this is self-explanatory. You can see the kind of buildings they built, that they were living in. They lived out there for weeks, and it was a muddy quagmire. It was like some kind of a refugee camp.

SE: So were you camping too?

LH: No, I didn’t camp. I just would go and come. just go and spend a day at a time.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Resurrection City at the Poor People's Campaign, 1968 |

LH: That gives you an idea of what those buildings looked like that they built. They built these things and it was like they had their own little village out there.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Resurrection City at the Poor People's Campaign, 1968 |

LH: And you can see some of the mud. That’s another good example.

SE: Yeah, all the planks that they were walking on to avoid the mud.

LH: Exactly, and this lady walking along with this little black girl, like this is where they live or something. It was just amazing.

|

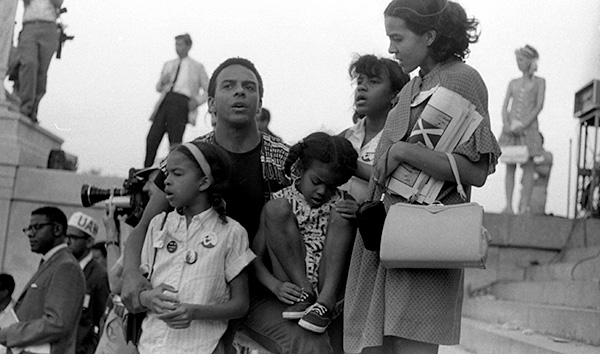

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Andrew Young with His Family at Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: Andrew Young was one of Martin Luther King’s chief aides. There he is with his daughters, and his wife Jean, and they were there at the rally. And look at that young Andrew Young. He was eventually the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. He got in a lot of trouble for interviewing—on his own—Yasser Arafat, and he was relieved from his position. While he was there, though, Jean was head of a thing they called the International Year of the Child, and she hooked me up with the U.S. Information Agency, introduced me to a lady there. I went down to show her my work. Eventually I started getting calls from the USIA, never met the people apart from the lady whom I went to see through Jean Young. They would call me to cover events in New York, and I covered some interesting events: luncheon with David Rockefeller; Queen Sirikit and her daughter from Thailand at the Waldorf Astoria; Michael Rockefeller opening at the Met, those kind of things. That’s where I met this guy, Nathan Cummings, who owned Sara Lee and Coach pocketbooks. This guy asked me to take a picture of him and his wife and I did, and he took them to his apartment—he lived in the Waldorf Towers—and every Christmas he’d send me a Christmas card with art from his collection. He had an expensive art collection. But that all came from Jean Young.

SE: That’s amazing.

LH: And she bought a small copy, and Andrew bought a larger copy, and I have a bigger copy he signed for me of that picture.

SE: Yeah.

|

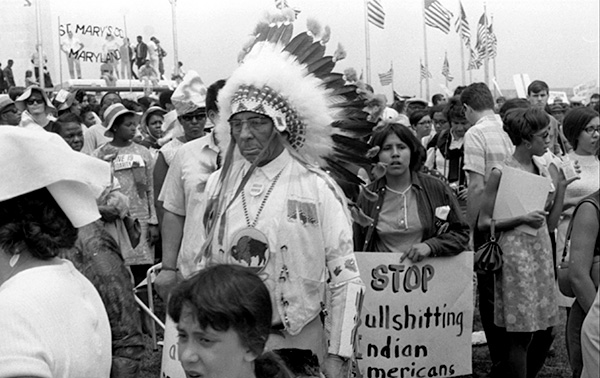

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: That’s self-explanatory. These are the kind of people who came to the Poor People’s Rally, by the way.

SE: Right.

LH: I mean, it was a diverse turnout of people. I understand people came from farthest from the South. I was told—I don’t know if it’s true—that some people came by mule-train. I don’t know if it’s true, but they were poor people who came from a long way. This Indian, he made it known. I just love the expression on his face.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Whitney Young, Head of the Urban League at Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: Whitney Young, head of the Urban League, he died in a drowning in Ghana. He was at the Poor People’s Campaign. He was wearing a button—the Urban League’s “equal” button.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: That’s another scene at the Solidarity Day at the Poor People’s Campaign. I just like the setup, the posture of the people, the body language. Those are the kind of things that get my attention.

|

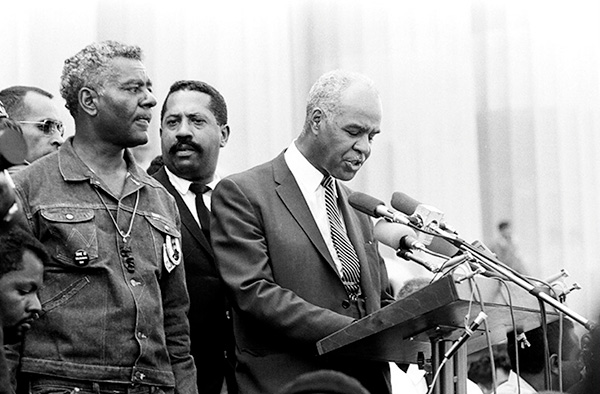

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Roy Wilkins Speaking during Solidarity Day on the Steps of the Lincoln Memorial, 1968 |

LH: That’s Roy Wilkins, NAACP head for years, and you can’t see him, but that’s Wyatt Tee Walker back there on the extreme left. Wyatt was from Petersburg, and he was another aide of Dr. King. Wyatt was major.

SE: Yeah, he was very involved here in helping to organize the sit-ins, both in Petersburg and then here, for Virginia Union.

LH: And one of my classmates from Virginia State is here, and I don’t know if you remember, but when Wyatt Tee Walker used to visit the campus a lot, he was what we called “clean.” He was dapper. We called him the “Bop Preacher” because he would bop around with his fine rags. I mean, the guy was clean. The “Bop Preacher.”

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Coretta Scott King and her children on the Lincoln Memorial steps, Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Solidarity Day, 1968. Mrs. King and her children: lower left is Yolanda, who died young; Martin III in the front; and Bernice, who’s now a minister herself—Reverend Bernice King.

SE: So let’s talk a little bit about this timeline . . .

LH: Okay

SE: . . . because some people in the audience lived through this and others did not.

LH: 1968, July, three months after King was assassinated. King was preparing for this, you know.

SE: Right.

LH: To me—I like it because of the expression on her face too; it would’ve been entirely different if she were looking straight up at me or something. There’s a somber poignancy to her expression.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Coretta Scott King, Senator Brooke (MA), and Martin Luther King, Sr. at Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: Mrs. King with Senator Ed Brooke from Massachusetts, and Daddy King: Dr. King’s father, Martin, Sr.

SE: And this is just three months after the assassination, so this is the culmination of all of the work that he had put into this. That’s what they were focused on.

LH: That’s right.

|

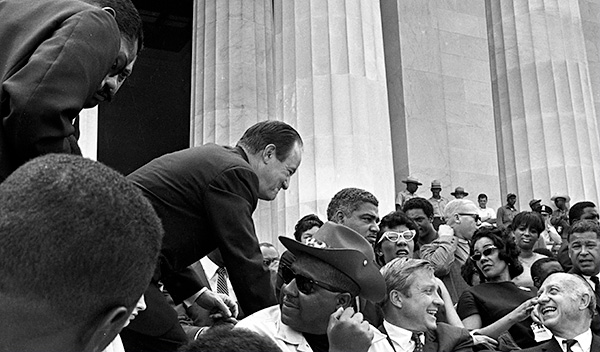

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Vice President Hubert Humphrey at Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: And there’s Vice President Humphrey; he showed up that day. There he was greeting—you can see Whitney Young back there. And then down in front you see Senator Charles Percy from Illinois, and Senator Jacob Javits from New York, and Mrs. King, and Ed Brooke again.

SE: It’s amazing: the backdrop of the columns, what you accomplished with scale in that, kind of compressing the crowd. It’s really a striking image.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: And of all the crowd scenes out there that day, that was one I liked most, with the people and the signs. I just like the graphic, the visual impact of them walking along that reflecting pool with those posters.

|

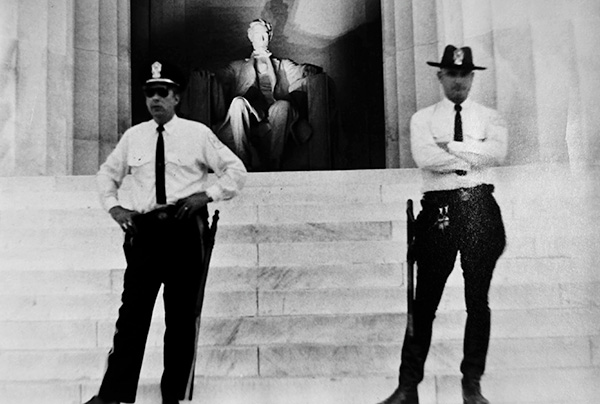

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Solidarity Day, 1968 |

LH: That’s my last shot at the end of that day. I just saw that and grabbed it. There these cops are and there’s Lincoln in the background. It can say any number of things if you let your imagination run wild, but I just thought visually it was a wonderful setup. Dramatic piece.

SE: That leads, then, into images—some of these were happening at the same time. It’s about the same time period the first few are: late 1960s.

LH: Right.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam Rally on Wall Street with Trinity Church in background, 1960s |

LH: I got involved in the Anti-War movement as a veteran, believe it or not. I came back and started getting out there on the street, documenting that stuff, because it was intense. There was a lot going on. You could not be interested in photography and not be out there.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam Protest, NY, 1960s |

LH: Of course, you know, this speaks for itself. The nuns—because I just thought with those peace doves—just visually and graphically, that worked for me.

SE: You have a number of nuns. Was that because there were so many nuns involved in the movement, or was that something you were drawn to almost graphically because of the habits? I mean that’s just a beautiful image with the white and black contrast.

LH: I just reacted to them with the white doves and their habits. That’s all I was thinking about. I just saw that.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Protest in Central Park, NY, 1960s |

LH: “Death in Vietnam, Hunger in the U.S.A.”

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Serviceman at Candlelight Vigil in Central Park, NY, mid 1960s |

LH: A soldier in a candlelight vigil against the war.

SE: Which was the similar position you were in yourself.

LH: Yeah, he was out there with the candle protesting the war.

|

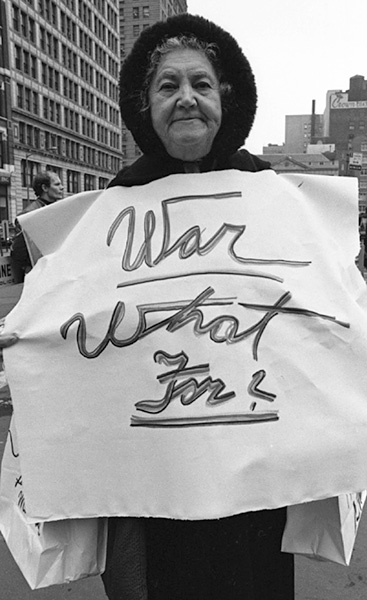

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam Protest, NY, 1960s |

LH: This old lady speaks for herself.

|

|

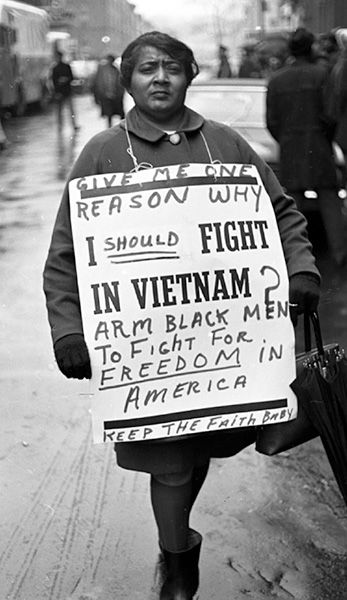

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam Protest, NY, 1960s |

LH: And that lady right there. I thought the two were similar in a lot of ways.

SE: That's a strong sign.

LH: It says "Give me one reason why I should," like she's going to fight there in the first place. But her point was well-taken, because she said "bring the GIs back home," "Let them fight for freedom in America." She was making her point.

|

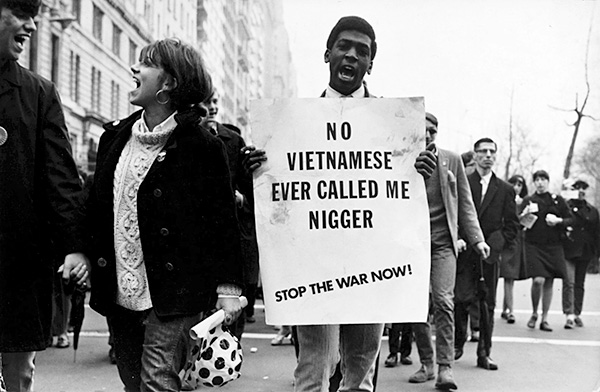

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson First Anti-Vietnam War Rally, Marchers on Madison Avenue, 1967 |

40:11

LH: That’s the first piece that the museum acquired from me. The very first piece. The very first piece. And that was the very first anti-war march, in March of ’67, I guess.

SE: ’67, and it was right after King gave his speech just before that march, in which he first came out against the war—

LH: Oh, okay.

SE:—which was, I think, a real turning point.

LH: They gave him a real hard time for speaking out against the war, too, you know.

SE: Right, and so I think this march, if I remember—it’s been a while since I did my research for my labels—but if I remember right, Stokely Carmichael was at that march that day, King was there—

LH: I’m not sure. No, I never saw King, by the way. Never did get to see him in person.

SE: So that was an important day, but I think it also is important to remember that turning point in 1967, because when Martin Luther King, Jr. came out to speak against the war, it was absolutely tied to the Civil Rights movement. And the power of those two forces together, I think, was—as you said—really difficult for him at that point, as far as the pushback, I guess I would say, from the government.

LH: They chastised him for speaking out against the war, said, “stick to civil rights.”

SE: Right.

LH: When you consider the number of black GIs over there . . .

SE: And that’s why the signs that you are capturing—I mean, that’s also something that you have a knack for: you were extremely attuned to the signs themselves, I think, when I look across your body of work. You’re not just capturing the message; you’re providing a visual context for the written image.

LH: And I did that subconsciously, but sometimes, I guess I was deliberate in it. Depending on the situation, I’d see it and capture it and recognize it for what it is.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam War Rally, NY, 1967 |

LH: And that’s coming down Madison Avenue. That was that first anti-Vietnam march. That’s just one of my favorite pictures from that period, from those images.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Scene in Brooklyn, New York, during street demonstration by students at nearby high school, 1970 |

LH: I told Sarah the story about this. I was teaching at this high school in Brooklyn. We were out in the streets; the kids were out there protesting in the street. They emptied the school. And the police were out there in large numbers. That space you see right there in the middle, that’s where I was in front of these policemen, walking along, and they were prodding us with nightsticks in our backs, moving us along. And I’d had enough. I just turned heel and aimed the camera right in their faces. In this day and time I probably would’ve been beat down to the ground, but I got away with it then. But the look on their faces said it all for me. Those sinister expressions.

SE: And it speaks to your direct involvement. This image gives you the sense of your proximity.

LH: I was there. It’s like, I was there, folks. You know?

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam War Protest, Central Park, NY, early 1970s |

LH: What I liked about this picture too: that was one of those anti-war rallies in Central Park. This is a mature man who’s an army veteran, retired. Depending on the color of that star on his cap he’s a lieutenant colonel or major. But anyway, this shows that this war wasn’t just protested by a bunch of young, wild folks on the street. And that woman in the background is holding her balloon. That day they let hundreds of black balloons go into the air, and I caught her before she let hers go.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam, Counter-Inaugural Nixon Rally, 1973 |

LH: That’s right in front of the White House, with Nixon. Right in front of the White House, at one of those gates. And that marine on the left, I’ve often wondered about. Said, “Wonder did this guy survive Vietnam?” Wondered about that.

|

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam, Counter-Inaugural Nixon Rally, 1973 |

LH: And that was the day when they had the anti-war, anti–Nixon, anti-his-second-Inauguration-Day. That was the same day.

SE: When we get to the contemporary protest photographs at the end, it’s very reminiscent.

LH: Oh yeah, reminiscent, of course. That’s the thing about when I did the protest show that combined the anti-Iraq and anti-Vietnam images: it was called Protest, and some of them you couldn’t tell the difference in when the time was—except, you know, I knew.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson The Bread and Puppet Players, Vietnam War Protesters, 1970s |

LH: Because that was the same day. That’s an anti-Vietnam, counter-Inaugural rally, and there were thousands of people out there. That particular day—the flags around the Washington Monument—the protesters lowered all the flags and ran Viet Cong flags up.

SE: I think we’ll get to that image in a minute.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam, Counter-Inaugural Nixon Rally, 1973 |

LH: I didn’t get the photograph in black and white of the Viet Cong flags, but I did get the black and white—that’s an international symbol of distress, as many of us know: the upside down flag.

SE: And that’s at the counter-Inaugural?

LH: Yeah, that’s at the counter-Inaugural. That’s one of the flagpoles around the Washington Monument.

SE: And they did that—nobody caught them. I mean, that takes some time—to get a flag down and put a flag back up.

LH: All that day, I don’t remember any kind of conflict with the police at all. All those people.

SE: So should we go back over a couple of these?

|

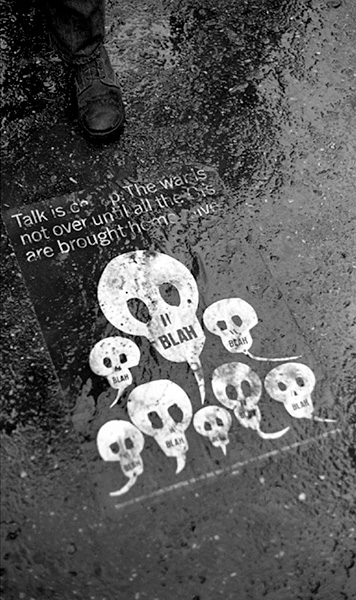

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Poster at Anti-Vietnam Protest, NY, 1970s |

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Vietnam protest with Phillip Berrigan, Washington D.C., 1970s |

LH: Oh yeah, that’s Phillip Berrigan, of the Berrigan brothers Catholic priests. They had a big mock rally with all of these people dressed like people in Vietnam, with mock coffins. Phillip was there; he was so active. His brother got in trouble. His brother broke into a military facility and poured sheep blood or something over military records. Daniel did that—Daniel Berrigan, I mean—they were outspoken activists, and this was Phillip.

SE: So this moves on to just about the same time period, actually.

LH: Oh yeah, because that was ’73, that anti-Nixon, anti-Inaugural thing.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Black Political Convention in Gary, IN, 1972 |

LH: And this is ’72 in Gary, Indiana. They had a Black Political Convention; it was truly in the spirit of a convention, with crowds of people from all the states with the signs. and all. That was a picture in the hall with all those people, and there’s Henry Marsh, Richmond’s mayor.

SE: And you went to school with him, right?

LH: I went to high school with Henry, yeah.

|

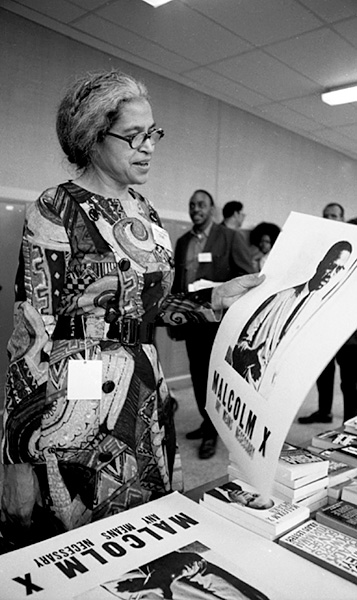

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Mrs. Rosa Parks at the Black Political Convention in Gary, IN, 1972 |

SE: So this picture. You describe this—you were just walking through the halls.

LH: I was walking through the hallway. At that high school where the convention was, they had a large hallway full of vendors. I was walking around, and I just happened to look. She was walking around like people didn’t even know who she was. Fortunately, I knew who she was, and there she is: Rosa Parks, looking at a poster of Malcolm X. It’s like the two of them were there together, almost. That picture’s been used several times in scholarly papers and books and so forth.

SE: It’s also a good example in time, because I think so often we freeze Rosa Parks in this 1955–56 moment.

LH: In the bus protesting.

SE: Right, at the beginning. Then we think of Malcolm X in a different moment in the movement, and she went on to have a—she spoke at Black Panther rallies . . .

LH: And this is a fortunate juxtaposition of an image and an iconic person in person. I sent her a picture of that. I didn’t hear from her, but someone representative did write me back.

SE: It’s a really striking combination.

LH: Yeah.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Bobby Seale and Jesse Jackson at the Black Political Convention in Gary, IN, 1972 |

LH: Jesse Jackson and Bobby Seale, one of the founders of the Black Panthers, at the Black Political Convention in Gary.

SE: And there is Marsh, of Virginia.

LH: Henry Marsh.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Coretta Scott King and Richard Hatcher at the Black Political Convention in Gary, IN, 1972 |

LH: And Mrs. King and Mayor Richard Hatcher, the mayor of Gary at the time. I guess he might’ve been the first black mayor of Gary, Indiana.

SE: These carry on with a number of people from the ’60s and ’70s.

|

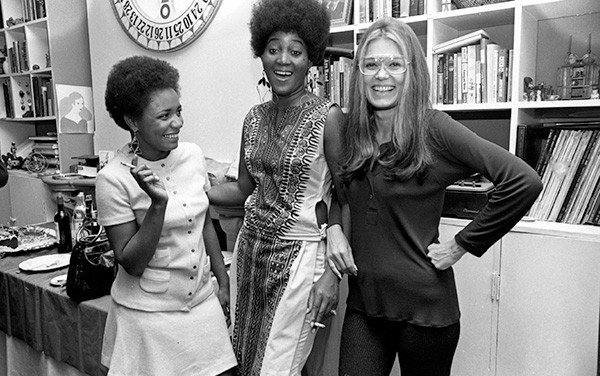

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Dorothy Pitman Hughes (center) with Gloria Steinem at Daycare Movement Reception, NY, mid 1960s |

LH: Yeah, ’60s and ’70s. This is Dorothy Pitman in the middle, who was involved with that Day Care movement. Gloria was one of the many prominent people who supported her and helped her raise money to build that beautiful, physical plant they built on West 80th Street, near Broadway. It was called the Day Care Alliance, and this was one of the many kinds of events they had where people came out to support her. There are pictures of the two of them, you may have seen, of the two of them with their fists raised, and they went around speaking on feminism in general.

SE: And it’s interesting to see how much childcare is a part of that.

LH: Oh yeah. Yeah.

|

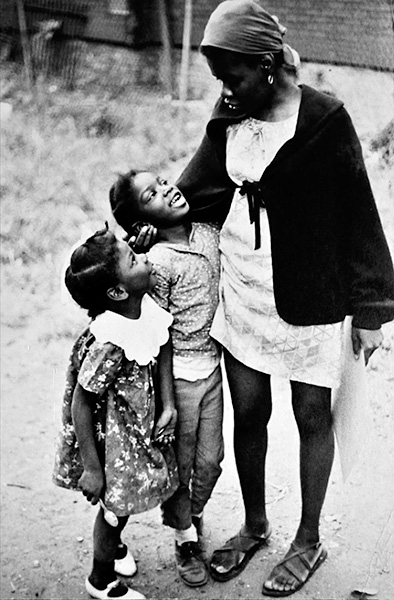

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Sister Noralita, Street Reading hosted by the New York Public Library, 1965-66 |

LH: This nun, Sister Noelita something [Noelita Marie]. New York Public Library’s summer street reading program. I captured her picture with those children, and then the figure following this . . .

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Delouise Blake Lee, 1971 |

LH: . . . is her after she’d left the convent, and there she is, still engaged with children. She started a foundation called the New Future Foundation. She’s very active in Harlem to this day; they refer to her as the “Mayor of Harlem,” unofficially, of course. Then she became Delois Blakely.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Stokely Carmichael at City College, NY, 1967 |

LH: There’s Stokely speaking at City College in ’67, dressed to the nines.

SE: As I hear he always was.

LH: Oh yeah, especially in public appearances like that. But it was just an interesting shot of him in a night with him gesturing and all—elegant. That was in Posing Beauty, the show that passed through here.

|

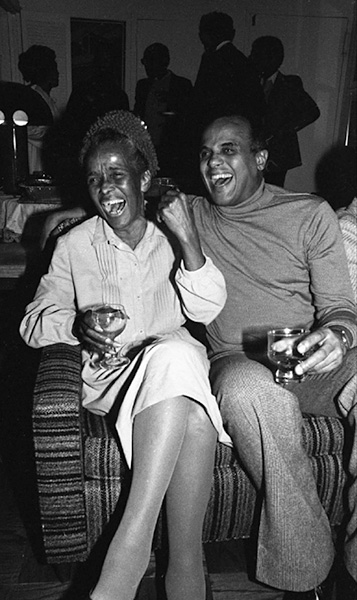

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Ella Baker and Harry Belafonte |

LH: That’s Mrs. Ella Baker, who was known as the mother of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC. That’s her at one of her birthday parties. I used to go to Mrs. Baker’s birthday parties. And there she is having a big laugh with Harry Belafonte.

SE: It’s a pretty great image.

LH: Yeah, because otherwise you wouldn’t know who she was.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Sun Ra, 1968 |

LH: Sun Ra. Anybody here who’s a jazz fan may have heard of him. He was known for his—not his orchestra, his Arkestra. And there’s an ankh on the wall, and there’s a light bulb Those elements worked for me. I had to go over there—I was on an assignment for an Italian media company, they were doing a thing on jazz, a book on jazz—and I had to go to Sun Ra’s walk-up apartment in the East Village where he had multiple tape recorders going at the same time. A lot of his band members were in this cramped, little fourth-floor walk-up, and on the door when I went in he had written a manifesto, and I had to read it first. He said, “Read that.” And I read that. And I just loved that picture of him. This guy took a whole orchestra and a bunch of dancers and did a performance in front of the Pyramids and the Sphinx. He was that far out. He was from Philadelphia. Sun Ra.

|

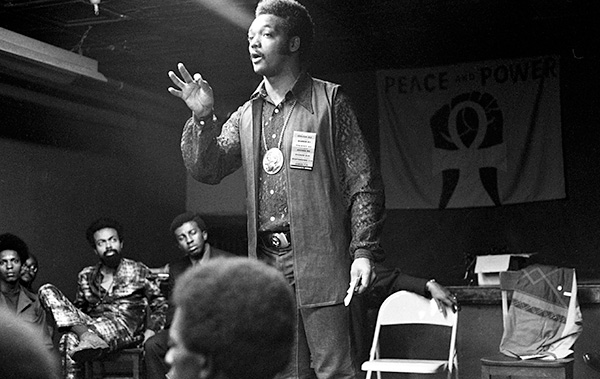

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Jesse Jackson at the Spirit House, Newark, NJ, 1970 |

LH: Jesse Jackson speaking at Leroy Jones’s—a.k.a. Amiri Baraka—Spirit House in Newark, New Jersey. I think that was in 1970. At the time Kenneth Gibson was running for mayor of Newark. Jesse’s wearing his big medallion with Martin Luther King’s face on it.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Fannie Lou Hamer, Abyssinian Baptist Church, NY, early 1970s |

LH: Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, in one of her better-looking pictures, because she was treated so badly. She was beat badly when she was imprisoned, and I caught her here looking very nice at Abyssinian Baptist Church, when there was something going on honoring Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

SE: Yes, and we’ve got another image of Hamer—Louis Draper’s image—upstairs . . .

LH: Louis Draper! Louis Draper. Nice image upstairs in that exhibit you're talking about.

SE: But this is very different; I love the contrast. His is a very straightforward . . .

LH: And she was the one who took a bunch of people to Philadelphia in ’68 for the political Democratic Convention and demanded that they be allowed to be delegates. And they tried to mollify her by offering her a couple of seats. And she said, “We didn’t come this far for no two seats.”

SE: That's powerful.

LH: And she was the one who coined that phrase, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Protest of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Abyssinian Baptist Church, NY, early 1970s |

SE: This is the same day, right?

LH: Same day. Outside, there was a rally in support of Adam Powell at this church. This lady had the audacity to be out there protesting against Adam, as he was well loved in Harlem. She had a handwritten sign saying, “Down With Adam,” and somebody punched her out. And I caught her crying afterwards. I think it was in Essence magazine, too.

SE: That image?

LH: The picture of her, yeah, that ended up in Essence magazine.

SE: I’ll have to look for that.

|

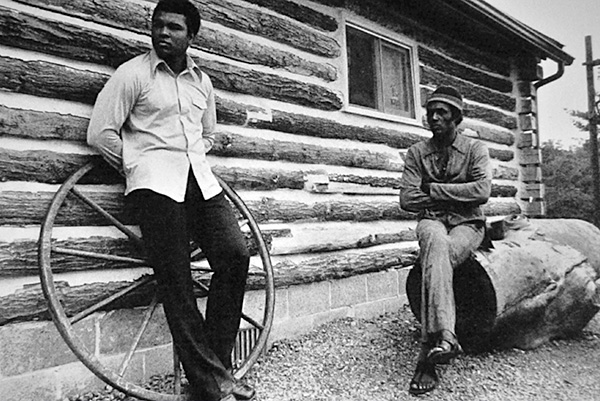

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Muhammed Ali and Calvin Lockhart, Deer Lake, PA, 1971 |

LH: And this is at Muhammad Ali’s training camp in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania. You could visit him on weekends. He was very open to having people visit him.

SE: And this is the person you were visiting with, right?

LH: Calvin Lockhart, an actor, who was in a lot of those “blaxploitation” movies, and that’s just a quiet moment. I was hanging out with them. I didn’t put it in there, but I even had a picture of Muhammad Ali and I punching at each other.

SE: That’s pretty good.

LH: Hey, I’m proud of that picture.

|

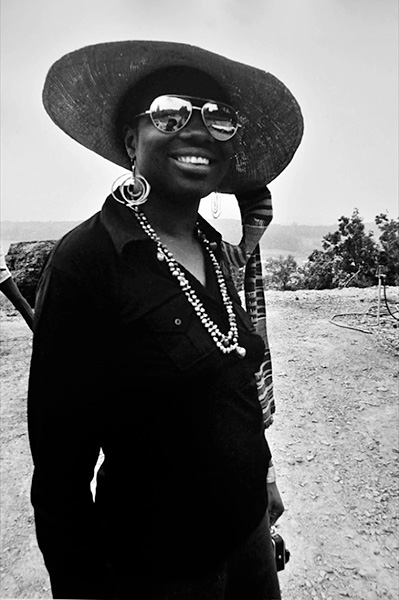

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Vertamae Grosvenor at Muhammed Ali's Training Camp, Deer Lake, PA, 1971 |

LH: This is Vertamae Grosvenor, who took me up there with Calvin to this training camp that weekend. She’s known for a book she wrote called Vibration Cooking, and also another book called Thursdays and Every Other Sunday Off, about domestic workers. She also, by the way, was in that film Daughters of the Dust, and the filmmaker Julie Dash is now doing a film on her called Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl. Verta took off at nineteen—took a ship to Paris at nineteen—and didn’t have a connection in the world, just went on her own. She had a regular program coming out of D.C. on NPR also. She just died a couple months ago.

SE: It’s a great image.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Dong King, Muhammed Ali and the Jackson Five, Plaza Hotel, New York, 1975 |

SE: There’s Muhammad Ali again, but in a very different context.

LH: Much different. This was a press conference for a fight coming up with a guy named Chuck Wepner. Here he is with the Jackson Five, and you might not recognize him, but that’s Michael on the right, folks! That’s Michael. I don’t mean to be naughty, but that was Michael when he was black. I couldn’t resist that.

|

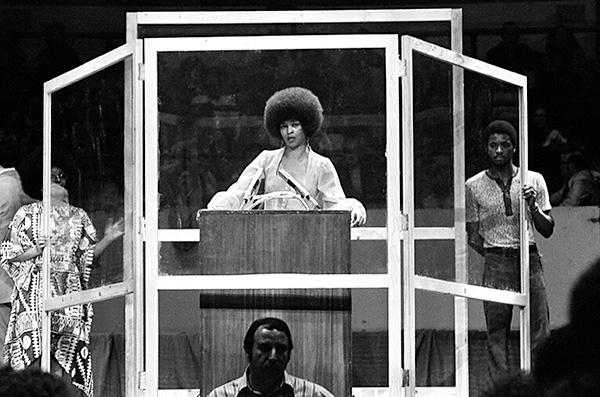

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Angela Davis, Madison Square Garden, 1975 |

LH: Angela Davis was on the FBI Most Wanted list for a long time. When they removed her from the list, she came out, and they had a rally at Madison Square Garden, full of people. And it's an mprovised, bulletproof shield in front of her and behind her. Out front the neo-Nazis were protesting her with their flags and their helmets and stuff. Nevertheless, there she was, 1975.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson President Jimmy Carter Campaigning for Reelection, Brooklyn, NY, 1980 |

LH: Jimmy Carter running for a second term, at Concord Baptist Church in Brooklyn, on top of the presidential limo. Yeah, he showed up and—matter of fact, inside—he was there, Muhammad Ali was there.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Joe Turner, expatriate Stride Piano Player, The Cookery in Greenwich Village, NY, c. 1980s |

LH: Joe Turner, expatriate stride piano player: stride piano—that’s that raucous piano style, you run up and down the keyboard. He lived in Paris, I think, and he was on his break from a club in the Village—in Greenwich Village—called “The Cookery.” Yeah, and he was on his break. I came walking by, and I couldn’t resist. I sat down and talked with this guy. Had the nicest conversation, and I got that picture. I love that photo. I love a lot of my stuff. I mean, nothing wrong with that; I’ve got to like it. How am I going to expect you to like it if I don’t?

|

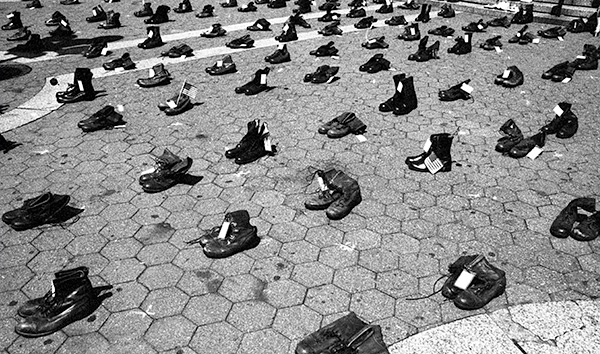

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Iraq War Protest, Union Square, NY 2003 |

SE: Now we’re moving into the twenty-first century. This is one, I think, where you said you could be confused when the image was taken . . .

LH: This was at the very early stages of the Iraq War. This is to commemorate the first nine hundred and seventy-eight killed in action. They had nine hundred and seventy-eight pairs of boots out there on the plaza in front of Union Square Park. Each one had a name, an identifying tag of the guy who was killed, and a lot of them had American flags. I just happened to pass by there on my way to work one day; I was teaching at a school a few blocks away. And that was a poignant image.

|

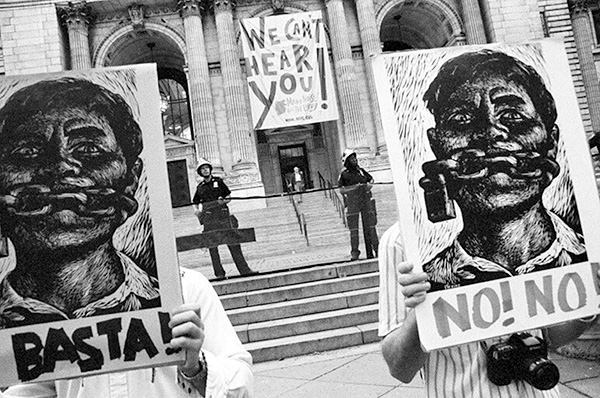

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Demonstration in front of the New York Public Library during the Republican National Convention, NY 2004 |

LH: During the Republican Convention, when Bush was running for the second term, this was in front of the New York Public Library. I just like graphically, visually, how that shapes up. And I must admit, just for visual impact, I purposely tilted my camera to get that kind of effect. I mean, you have to deliberately visualize in your eye, real quickly, what will present the image the best way. And on the left it said, “Basta,” which means, in Spanish, “Enough!” and “No! No!” And that sign in the background on the public library had nothing to do with the signs in the foreground. but it said “We can’t hear you,” and somehow that seemed to connect.

SE: Yeah, I had no idea they were not connected.

LH: That had nothing to do with it, but it just worked. I think I might have noticed that. I’m not sure.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Iraq Demonstration, Washington, D.C., 2003 |

LH: This is a good one. This is in Washington, D.C., during the anti-Iraq war rallies, and I think this is funny. They just came out making a spoof of this whole thing about making a profit from the war. Yeah.

SE: So.

LH: Uh-oh.

SE: Yeah, maybe we should go back in time . . . You told me, and it’s understandable, when I asked about how far forward you wanted to bring your protest images, and you mentioned that you were a little bit leery.

LH: Demonstration fatigue or something—but I could not let this thing happen in New York—what we are about to come to—I could not—seriously, I could not let this go down without getting some of the imagery. I’d have been terribly remiss.

SE: Right, and we were talking about the Nixon images, so I wanted to ask you what it feels like, at this point in your career, looking back: what does this familiarity feel like? How familiar does it feel? Or how different does it feel?

LH: Mainly it’s a continuum of people expressing their feelings about a situation.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

HL: And believe me, they were not happy after the election.

SE: Yeah.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

LH: “Not Mein Führer,” that’s right.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

LH: “Fear monger.” “Misogynist.”

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

LH: I mean, “Make America great without hate”? And this thing about “Make America Great”? It’s so great, anyway. I mean, he didn’t have to make America great. And furthermore, if you’re talking about “make America great” which period are you talking about going back to? Okay . . .

SE: That is the question.

LH: . . . because we’ve been through some periods that weren’t too great, folks.

|

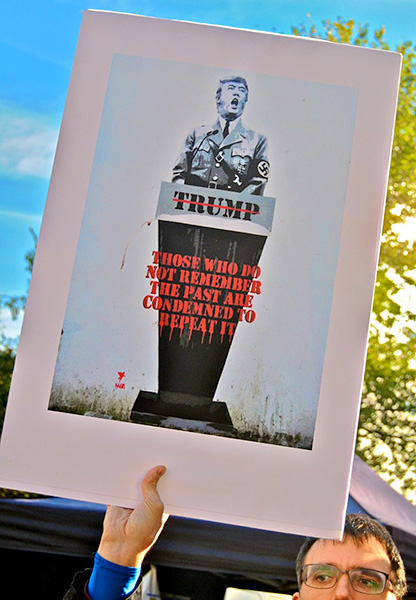

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

SE: That one’s . . .

LH: Go back! I had to—I just had to do that. I had to do that. I’m sorry. Whew. Okay.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

LH: There he is, looking like Hitler.

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

LH: I’ll tell you, it’s kind of frightening, though, the kind of mood that—all this is about a month now, and this climate, the choices of people, and the people he’s putting in places is scary. But I don’t say too much about that because I don’t ever know who I’m talking to. I keep quiet about that.

SE: Well, you don’t have to . . .

|

| Artist: LeRoy Henderson Anti-Trump Protest, Union Square March up 5th Avenue, 2016 |

LH: This one: Hitler, Mussolini, Putin, and Trump. I have nothing to say.

SE: Well, but you are documenting—you’ve talked to me about how you just felt drawn to document the time.

LH: Yeah, it was really a genuine desire. First of all, I loved photography, and I wanted to use that medium to do what I’ve seen others before me do. That is, document things happening in their time. That might sound like a lofty, kind of a self-appointed importance, but it’s not. I was inspired by what had gone before me, and it was a privilege to be able to use this medium, and try to do what others have done, and do it sincerely. And not do it as any kind of self-aggrandizement, but just do it because it’s happening, and this is the medium I use. If you claim to do something, it’s like, "all right, where’s the proof"? So this is my proof. Where’s the proof? You know, just that simple. ![]()

Contributor’s Notes: LeRoy Henderson

Contributor’s Notes: Sarah Eckhardt