print preview

print previewback CHELSEA GILLENWATER

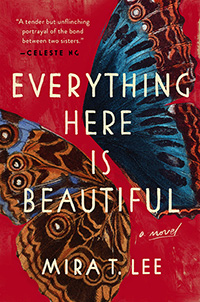

Review | Everything Here Is Beautiful

Mira T. Lee

Pamela Dorman Books/Viking, 2018

|

In her vibrant debut novel, Everything Here Is Beautiful, Mira T. Lee shows herself to be a promising and confident writer who has risen to the task of exploring mental illness with exquisite care. The novel brings with it a certain swagger, and the first hint is in the title itself. It’s simple, sure, and expansive—a perfect description for the novel’s daring moves through time and space, all graced with character work that is both tender and tough. Everything Here Is Beautiful, as a phrase, reads like a solemn promise: that what we are about to read is something to be savored, understood, longed for. But Lee strips away the gloss of what we might consider “beautiful” and brings us into something more messy and frightening—but still somehow enchanting.

The novel primarily centers around Lucia Bok, a spirited Chinese American woman who begins to experience episodes of schizophrenia in college, with a cocktail of symptoms that makes her diagnosis shift over time. Her older sister, Miranda, is always trying to manage the illness, creating a rift between Lucia and Miranda that grows deeper and deeper with each passing year.

Through all this, Lucia is determined to find her own life—a journey that takes her through multiple relationships and locales, from a psychiatric ward in New York to the beautiful countryside of Ecuador. She flies from place to place with a restless energy that makes the other characters nervous, and between all these milestones, she still hears strange (but familiar) voices inside her head, telling her how wrong she is to want what she wants. And when Lucia spirals into another psychotic episode immediately after her first baby is born, her friends and family try to hold her together through sheer force of will. The scope of the novel is huge, and Lee uses the tension between Lucia and the outside world to deal with themes of choice, identity, and responsibility; Everything Here Is Beautiful consistently unsettles and surprises readers in a way that makes the read all the more satisfying.

One of the great feats Lee accomplishes involves her approach to Lucia herself. Lee captures the horror of mental illness without dehumanizing Lucia and ably expresses the everyday frustrations that accompany such misunderstood disorders. Lucia has moments of what her sister calls “insight,” the ability of a patient to “see through” her own anxious thoughts and ground herself in the real world. But even in her lucid moments, Lucia can’t always hide her contempt for the well-meaning cycle of doctors, nurses, orderlies, and therapists trying to unlock her like a puzzle:

He’s already run the standard battery of questions, checked the check boxes, computed the data: hears voices = schizophrenic; too agitated = paranoid; too bright = manic; too moody = bipolar; and of course everyone knows a depressive, a suicidal, and if you’re all-around too unruly or obstructive or treatment resistant like a superbug, you get slapped with a personality disorder, too. In Crote Six [the psychiatric ward], they said I “suffer” from schizoaffective disorder. That’s like the sampler plate of diagnoses, Best of Everything.

Lucia does not come to Crote Six of her own volition: she’s brought in after acting not-quite-normal at a doctor’s checkup with her newborn, and after the baby’s father, Manuel, finds her ignoring her child’s cries, speaking in strange circles about being watched. Manuel and Miranda, both fearful of what Lucia might do, steer the narration for the first third of the book, and both characters seem as trapped in their own anxiety as Lucia is in her paranoia. Lee uses their points of view to ramp up the tension, and it’s not until after Lucia graduates from the outpatient clinic that we get to hear from her in her own words. It’s a great choice, structured so that we’re rewarded with insight into Lucia’s character as she starts to see herself more plainly.

The force of Lucia’s mania makes the world around her glow, and Lee channels incredible lyrical power into rendering the heat and clamor and joy of the busy streets of New York, or the sticky summers of Ecuador. But Lee reserves her sharpest, most searing images for interior spaces. In her dreams, Miranda imagines Lucia’s mind as enemy territory, repelling her at every turn, Lee’s fevered prose rising with Miranda’s panic:

she was diving headfirst into her sister’s dark, vacuous eyes, swimming behind the eyeballs, clawing with tiny, ineffectual fingernails that sprouted into giant pitchforks, burning red like the devil’s, and she would stab, more violently, with her body in every blow, screaming, Where are you? Where the fuck are you, Lucia?

The search for the “real Lucia” occupies every character in the novel, including Lucia herself. Lee keeps us on our toes with shifting perspectives and timelines, sliding from first person to an omniscient third depending on how present Lucia is in her own mind. The more she dissociates, the more clouded things feel, the more time seems to blur. Even when the narration keeps us at a distance, we still feel fully connected to the characters’ emotional states, a trick that justifies many experimental quirks in the novel’s structure.

That narrative rhythm pulls us right into the heart of Lucia’s mania, and the novel shines when Lee helps us feel the tight panic of being in a room with someone (your wife, your sister, your self) who cannot be reasoned with. Those scenes crackle with dark energy, each word a punch as the narration gets more and more frantic, unable to distinguish between characters.

Where are the pills? Pills, pills, pills. Always the pills. The pills like a leash around her neck and everyone with a hand to pull. It’s wrong, Lucia. Too loud, too electric, she lashes out, all arms and fists. You want pills, here are the pills . . .

Lee seems most at home in the rich interiority of her characters. She brings their rage and helplessness to vivid life without sensationalizing the subject or boring her readers. But that microscopic lens that helps her dive deep into the intricacies of her characters’ motivations sometimes goes blurry when we zoom out again. Numerous secondary characters and subplots sort of dip in and out, and the book jumps from New York to Switzerland to Ecuador to Minnesota in a way that starts to feel a bit labored, especially since the settings don’t apply equal weight to the narrative. The book sprawls like that sometimes, just a little uneven at the edges, but it does support Lee’s multicultural mosaic, a world where anything—driven by coincidence or impulse or need—can happen.

The novel’s strongest theme concerns how far humans will go to retain the sanctity of their free will. Lucia struggles to maintain agency in her life, even at the expense of her health. Lucia’s husband, an outspoken, one-armed Jewish man from Russia named Yonah, laments, “This is jail,” when Lucia is confined to a hospital. And Manuel spends the early sections of the novel in America, an Ecuadorian with no papers and fearing deportation at every moment. Even when circumstance ensnares them, Lee’s characters howl for the ability to define themselves apart from systems—from family or country or illness. As Lucia says at one point: “I don’t want to suffer. I want to live.” The novel’s boldness here is what makes it so memorable; there’s something indelibly defiant about insisting on being seen as a unique—even beautiful—being, an individual torn between the desire to belong to a community and to escape into a place where you alone hold the power to be who you want.

This, Lucia says, is what we want:

People think of home as a single fixed place, but when I went traveling, I found the community of extended family I’d never had. Later, I learned there’s a Spanish word for this: querencia. It refers to that place in the ring where a bull feels strongest, safest, where it returns again and again to renew its strength. It’s the place we’re most comfortable, where we know who we are—where we feel our most authentic selves.

But Lucia may have found another word for it—saudade, Portuguese for “a vague longing for something that cannot exist again, or perhaps never existed.” The answers to their problems may not exist for Lee’s characters, but what Everything Here Is Beautiful shows is that we all want what is lovely and good and kind, but when life doesn’t help us out, we find them ourselves, somewhere beautiful. ![]()

Mira T. Lee is the author of Everything Here Is Beautiful (Pamela Dorman Books, 2018). Her fiction has appeared in The Southern Review, Gettysburg Review, The Missouri Review, and elsewhere. She is a recipient of the 2012 Artist’s Fellowship from the Massachusetts Cultural Council.