print preview

print previewback CATHERINE MACDONALD

Until There Is Nothing Else to Tell

|

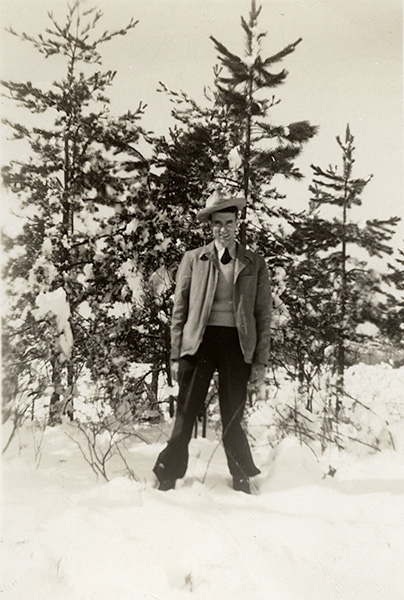

| Claude Emerson, father of poet Claudia Emerson Photo courtesty of Kent Ippolito |

Poems from Claudia Emerson’s Claude before Time and Space land in my inbox, singly or in small batches, throughout the late spring and summer of 2014. Ten poems from what will be the book’s title sequence arrive in mid-March, without preface or instruction. I know that despite the exhaustions of her cancer treatment and the arrival of troubling new symptoms, Claudia’s poems are being written. And so this message feels urgent, and I read the poems urgently. I read them over and over and write back to her the same day:

I am very taken with these; the language is crystal clear and a girl’s preoccupation with her father, how early on he interprets and represents the dangers and mystery of the world is all here. Does that make sense? Very rich material and the eccentric organization of the sonnet (3, 3, 2, 3, 3) support the voice and material. I like how Claude and the “you” merge and then come apart in different sections. (“Yourself in the mirror, with him,” “to prove / what you already know.”) Love this moment: “it’s slick—he leans over, slips the sock off / your foot—as this.” Lots of good stuff.

Claudia has told me that me that the “Claude poems” have been moving through her for some time, and that she is surer now of their shape and tone. Texting me from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference in July 2014, she says that she will include one or two of them in her reading there, but is “anxious” about them. “Do you like them?” she asks me. I do. They are odd, simultaneously fabulous and literal, but she is compelled by them, and I am too. She has long known that the title for this sequence is “Claude before Time and Space.” I think she also knew that these would be the core of her last volume, though we didn’t speak about that then.

Other poems from Claude before Time and Space arrive in April, June, August, and September: “Bird Ephemera” (followed by her gift to me of a copy of Emma Bell Miles’s Our Southern Birds); “A Life Beyond”; “Midwife” (a poem based loosely on the life and work of Tennessee midwife Ina May Gaskin, and which, after revision, shifts from second person to first); “Lacuna”; and “Child of the Desolate”—all concerned with beginnings, endings, and miracles withheld.

~

Ellen Bryant Voigt observed that Claudia’s “great twin gifts” are “figuration” and “empathy,” and these gifts are not diminished by cancer’s assault. In this late work, Claudia plumbs the fault lines between language and memory with intense concentration and marvelous imagery, solving the problem of how to form each poem as it comes to her.

If in poetry the universal is realized only through writing the particular, then the selection, ordering, and development of detail is what makes a true poem. Singular in their careful observation and reportage, Claudia’s late poems are precise and crafted, but not plotted or plodding. There is narrative, but it is a capacious and improvisatory storytelling. From “Bird Ephemera”:

barred owls unseen

caterwaul vesper

sparrows chimney

swifts crisscross intricate

etching of afterimage

their delight in emptying the sky

emptying the eye mine

in the dooryard the swept it is not

real elegance of a finished thing

I think of Phillip Larkin’s statement that each poem should be “its own sole freshly created universe.” I believe these poems, wrung from hard work in the face of terrifying illness and continuous loss, meet that standard.

~

Frequent topic of conversation that summer: a large barred owl that lives part-time in our city yard—a novelty at first, but then the creature steadily decimates the goldfish population in our small pond. Still, it’s pretty wonderful to have this dark magnificence in occasional residence. At dinner one evening with Claudia and her husband, Kent Ippolito, as guests, we see the owl swoop down from its perch and catch a large goldfish. No one is keener to observe this depredation than Claudia, who watches the bird for many minutes. Months later, when I search for a photo of this moment, one that I am sure someone snapped—Claudia in the near distance, her back to us, head tilted to study the owl on a limb with its prey—I realize the photo never existed. There are only photos of the predator, prey.

What effect did the long illness have on her work? Certainly it gave Claudia full access to Dickinson’s “flood subject,” immortality, and its counter, mortality. Already an intimate of the vanished, in Claude before Time and Space, the poet immerses us in a death-rattling world where time, our sternest measure, binds us in a kind of quantum entanglement with all we have known and with all the future witholds. The book opens with “Swimming Alone,” an elegy for a beloved friend and scholar, Ann Beal, who died in May 2014, a few months before Claudia. The poem unfolds with the languor of a Virginia summer day as two old friends meet to swim at an abandoned farm pond, the water still and warm, but not neutral or neutered: a beaver sounds a warning with slap of its tail; “a snake’s / head threading the air / above its body” passes the swimmers; a dragonfly appears, “its body broken // into syllables.” Nothing is as simple as the setting might suggest. Told in the present tense, the speaker acknowledges that learning of this friend’s impending death makes a way forward for her into what is at once unknowable but imaginable, like “the living / we have yet to do.” Of this friend, the speaker observes:

So when, now, this

afternoon years impossiblypast, I learn she is dying,

there is selfish comfort

in knowing she is doing thisthing before me, the way

she is in the middle

of the pond before Ican get there . . .

~

On a walk by the James River near Claudia and Kent’s home, she tells me she’s read about how some cancers inexplicably resolve after the sufferer is scorched by a fever, one that arises apart from the cancer but destroys it. In her poem “Spontaneous Remission,” the speaker invokes just such a fever:

And so, why not,

I consider how

I might engender it,immunized

as I have been against

all but what hastaken this hold

in me. . . .

This poem holds two critical images, and the first inspired the book’s cover illustration. Claudia gives us the “slim pins” of a dandelion’s “crazed halo” of seed that the speaker might “blow out / like a flame.” There’s also, most movingly, the collection's second glimpse of the speaker’s father, Claude, who keeps a fire of banked coal and ash alive, a possible means for the speaker to burn and by burning, heal. The poem’s closing is devastating in its hopefulness as it draws together the imagery of seed, childhood, fire and water, and finally, a rogue and absolute deity:

And when I wake

as from the childhood

bed, it will have

broken, all of it,the veil of seeded

water on my brow

a sign there: somethingatomized, cast

out, now, blown away,

by the arson that hasbecome the God in me.

Claude before Time and Space closes with the poem “Match,” in which these images of seed and fire are resurrected again in father Claude’s ability to

tend one fire for an entire winter—lighting it

sometime after the first frost with the timingof a backward garden . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .banking coals in their inscape of ash, where you

find them alive in the morning, coax themthe way you might a bloom’s eclosion

from seed. . . .

Ouroboros: a progenitor, an inheritor, a beginning and an ending indissolubly joined.

~

Thanksgiving, 2014: my father is sick, and worsening, and Claudia is too. In my father—though there’s no clear picture—we see weight loss, abdominal pain, and exhaustion. But he declares himself just old; visits with his doctor yield no diagnosis. Yet we are headed toward crisis; there will be a moment when we will just know. I plan to attend his next doctor’s appointment, though he is reluctant to include me.

~

Odysseus to the noble swineherd, Eumaeus:

But you

can see in the stubble how the grain once grew,

Though I am crushed by grief.

(Homer, The Odyssey, translated by Emily Wilson)

~

When Claudia is well enough that fall, I visit, and we talk about poems or gossip or simply sit on her screened porch and watch the birds visiting the elaborate and noisily congested backyard feeders built for her by her husband Kent. As the fall advances, she is often not up for visits. Soon, the texts and emails from her—once regular, often heart-stopping—diminish in frequency.

The versions of the Claude poems that I read in March 2014 vary little from those in the finished book. Titles will change, from “Claude’s Dream of the Garden” to “Recurrence,” from “Claude Tells the Ghost Road” to simply “Ghost-Road”—her father’s name, from which hers is derived, is erased from each title. It pains me now to consider this erasure, through which she must have tracked her own panic and reckoning as her cancer spread, causing partial blindness, bone fractures, and enervation.

~

In that last year, Claudia argued with herself, briefly returning to the Presbyterian Church of her childhood, then declaring herself a contemporary transcendentalist. She discarded all timepieces, like a healthy animal who travels seasons, not days or minutes or hours, while scheduling surgeries, scans, and still mentoring young poets from VCU. She allied herself with every down-and-outer and challenged the scofflaw owners of unruly dogs in the city park near her home. She withdrew from relationships that burdened her (one memorable Facebook post: “One can, indeed, in this air, forgive—and unfriend,” accompanied by a photo of a rusty-cheeked, downcast cherub), even as she gave her time, insight, and intelligence to students, friends, and family.

Once, after a discouraging Sunday sermon, she left church in downtown Richmond and chose to go home another way, crossing the James over Mayo’s Bridge, the city’s oldest and lowest, hers the only car on it. She passed an elderly man who hailed her to stop. Stop she did, and without a word, handed him a hundred dollar bill (she sometimes cashed checks from readings—gigs, as she called them—and then treated the cash like a windfall), and drove on. In the rearview mirror, she watched as he waved the bill above his head and dance-stepped away.

~

I am driving Claudia home after an event on VCU’s campus on a balmy September evening. By this time, the cancer’s metastasis to her brain has distorted her vision, and she is no longer able to drive. As we cross the James River, she points out shimmering points of light scattered over the rocks below us. I have never seen this before, though I have lived in this city for years. These are campfires, she says, made by the river’s celebrants and its transients, its wild young, who circle and range over the granite boulders marking the Fall Line.

~

As I write this, I have Claude before Time and Space open beside me, these poems made despite and because of the anxiety, confusion, and exorbitant toll of mortal illness. Though conjured in the privacy of that illness, they are fully public now, and seem to me no less extraordinary than when they made their way into the world in the months before her death on December 4, 2014.

Five weeks after Claudia died, my father was diagnosed with stage IV ureteral cancer and dementia, and I left my job and home to join my brothers and sisters as we tried to negotiate the fraught time left with this difficult man. During those months, so soon after Claudia’s death, I often reread the poems she’d shared with me in late 2014 and then celebrated the publication of her penultimate book, Impossible Bottle, in September 2015, the month in which my father died. But it is the poems in Claude before Time and Space that give back to me her world then, wearying and worrying, as well as the continuing gift of her empathy, wit, imagination, and linguistic intelligence:

In this, you suppose you could find the what to blame:

its coming and going too much the same; you can

still hear it—the too-straight of an emptying way.

(Claudia Emerson, “Ghost-Road”) ![]()

The essay’s title is a phrase from Emerson’s “Birth Narrative” in Claude before Time and Space.

The quotation from “Bird Ephemera” here retains italics as published in Blackbird v13n2 that do not appear in the book.