print preview

print previewback CASSIE PRUYN

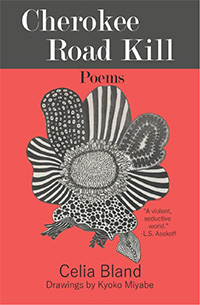

Review | Cherokee Road Kill

Celia Bland

Dr. Cicero Books, 2017

|

Set in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, Celia Bland’s third poetry collection, Cherokee Road Kill, unfolds over the course of two unnamed sections. Like the accompanying drawings by artist Kyoko Miyabe, the poems are etched with exquisite detail. Throughout the book, Nantahala, a New Deal–era man-made lake that drowned a Cherokee town, surfaces time and time again, offering up a metaphor that serves to illuminate Cherokee Road Kill’s conceit. Bland’s collection is about memory of place, about diving deep into the once-was, about visiting, as the poem “Dammed” illuminates, “cedar-shingled cabins & / smokehouses / slick with underwater”—about the poet’s grief and reverence for those buried by history.

Cherokee Road Kill’s title poem connects the landscape with the events that come to haunt it:

Every year, spring snow

sugars the road. Every spring a lank-

haired son of Sequoyah High School

closes long lashed eyes

in Cullowhee and opens them—?

Steeped in history, the landscape is lush and beautiful and dangerous, made tangible, moreover, by Bland’s muscular language. She deftly handles vocabulary that might be clunky in others’ hands: words like “carapace,” “pulchritudinous,” “latitudinally,” or the apparently poet-invented adjective “cunnilar” in the poem “Croatan” (as in, “A whole year is cunnilar, / a hold or a dirty vessel, an ill-washed cup reamed with / milk . . .”). She switches effortlessly between registers: in “Cherokee Hogscape” she describes the pigs’ “tensile snouts like chestnut halves” soon after a voice rings out “hogs’ll knock you down and chaw yr eyeballs out of / the socket. I seen ‘em.” Bland injects the poems with condensed sounds without allowing them to spill over, as in “Dammed”:

Tobacco clots before it’s combed.

Call it cash crop and cuss its shag

clotted, combed, carded, and shredded

like Carolina barbeque.Its stink delectable earth and the truffle

of silver coin, Ka-ga-la.

The collection’s first section is chock-full of car crashes, funerals, and legends. We encounter cousin Stanley, Guy Mooney, Cousin Jennalee, Kenny Arrowhead, and Maw Maw. When the second section announces itself, we expect to continue on with the same compelling cast of characters. The focus narrows, however, following only two characters, chronicling not a litany of deaths but one death in particular.

In the first poem of the collection’s second section, “If I Were Another,” we meet Louise. The connection between the speaker and her subject is immediate and tender: “Louise calls at 2 am, whispering, ‘It’s Louise.’ / Louise rings like a crescent moon illuminating the valley.” In “Praise Be Books & Gifts,” through a rare moment of direct narrative, the speaker confirms that Louise’s story is a tragic one:

And Louise, whose hair hung in two halves like honey.

Surrounded by the books I stole.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This was before he killed her.

From this point on, Louise’s role in the speaker’s life isn’t further explicated; instead, the poems give voice to the developing relationship between Louise and the man who becomes her rapist and murderer. In the poem “Chicken Shit,” when Louise meets him at the correctional facility where she’s teaching a class, Bland’s staccato delivery conjures the threatening scene:

When she turned to write

in chalk, her

hair swung.

I coulddip my finger into her

skin some thing

muttered. Creamy.It was him.

The book’s second section traces the sexual violence that immediately follows his release from the facility, their fraught relationship, her termination of the resulting pregnancy, and her murder.

Throughout Cherokee Road Kill, Bland engages with the landscape and loved ones of her upbringing, though she allows her speaker access to characters and events she could not possibly have had herself. Although the scenes between Louise and the unnamed man are necessarily figments of the poet’s imagination, they unspool like film clips without narration. As the second section’s epigraph by Flannery O’Connor suggests, the poems’ details serve to implicate the speaker, the community, the collective “we”: “What about these dead people I am living with? . . . We who live will have to pay for their deaths.” Repetition of words and details reveals that the unnamed offender in the second section is the same man described in several poems of the first. The murderer is humanized through descriptions of his childhood, his experience in prison, and his anger and bitterness, even if the speaker in no way absolves him.

The collection culminates with a haunting set of poems depicting Louise’s death. Haunting, especially, in the way the speaker is patient in her descriptions; the moment’s elongation expresses most clearly the speaker’s grief at the loss of Louise. The poem “Trail of Tears” opens:

Dying, she heard the hiss

of radiator. Her hand a leaf

on the floor where he’d dropped it

leaves scattering in the wind of

lungs slit and leaking.

Soon after “Trail of Tears,” the book ends. Its two-section structure is lent an extra element of surprise given the book’s plot. Perhaps as readers we’ve gotten used to the triangular symmetry of the three-section structure common in contemporary poetry collections. But in Cherokee Road Kill, no final sequence swoops in, after a pause, to process the intimate violence. Although the ending isn’t premature or even necessarily abrupt, it leaves the reader feeling raw, vulnerable, and intensely moved. No explanations are offered, no gushing emotion follows the book’s visceral climax—simply a poem or two that read like brief codas, then empty space.

The decision to structure the book this way is mirrored in the poet’s treatment of her subject matter throughout. In a gesture of deep respect for both her characters and for her youth, the speaker brings the landscape and its inhabitants, past and present, to life—a performance of memory and imagination—but does so with only the subtlest of narrative framing. Rather, the collection’s emotional urgency—the speaker’s grief and nostalgia, her processing of history, ancestry, and loss—is evoked through word choice and diction, through the care taken with the poems themselves. As Robert Kelly writes in the collection’s preface, the poems don’t “turn their backs” on the stories they bring to life, but neither do they “obsess” over them. A book with grief at its center that, nonetheless, refuses to obsess over its grief—this is what makes Cherokee Road Kill unique, unsettling, and undeniably memorable. ![]()