print preview

print previewback WESLEY GIBSON

Voice-Over

1708 Gallery,

Richmond, Virginia,

May 2–24, 1997

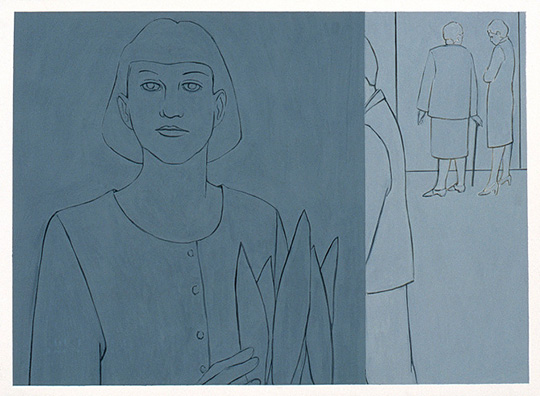

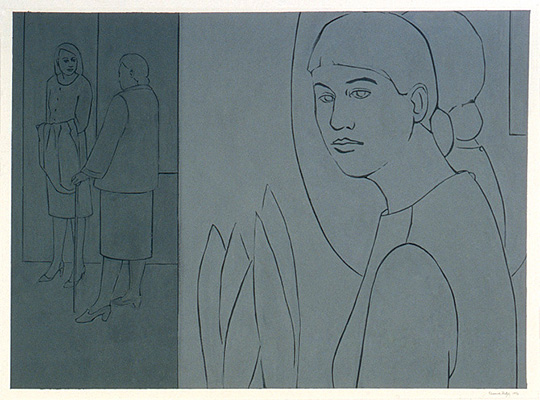

I was always struck, when I talked to others about the work of Eleanor Rufty (either when the work was actually in front of us, or later, when it was not) by the absolute authority with which people would tell me what the work was “about.” They were about alienation (that tired old phrase). A woman was readying herself for a cocktail party. She was at an opening. That was her mother, her sister, her father. Really? I’d think, glancing over, thinking back. I was never so sure; and I was almost certain that I wasn’t mean to be so sure. The paintings and drawings seemed (forcefully to my eye) to be guiding me away from the literary, the psychological. Away from narrative. The compositions, for example, never seemed to define a naturalistic space, and further, seemed actually to announce themselves as shapes. The backgrounds—which I call backgrounds purely for convenience—through their density and weight, the relationship between the colors, where in how their lines met looked not like rooms at all, or even like suggestions of psychological space. They look like groups of lines or blocks of color in relationship to one another. They looked, even when they seemed to define a space for figures to stand in (and upon closer inspection almost never did) as self-consciously concerned with the formal elements of painting as the most rigorous abstractions. The figures looked to me, first, like figures placed in relationship to one another on paper or canvas. A photo-realist painting, for example, does this too; but a photo-realist painting doesn’t call attention to the mechanics of painting the way a Rufty painting does.

|

| Eleanor Rufty Voice-Over, No. 6, 1995 Gouache 22 x 30 inches |

Look at the way she handles space. She recalls, deliberately I think, the space of early Renaissance painting and the framing devices of Matisse. Her paintings and drawings have always read more like mediations on the figure rather than the brash renderings of people in places. There’s a whole history in them. They seem to me more intellectual in their concerns than either psychological or literary. They seem to be asking formal questions about the nature of the figure in drawing and painting. They have an awareness of Piero della Francesca, where the blocks of space define a world in which God is as real and as present as a fold of drapery. Angels may inhabit one block, human beings another; but there is kind of flattening puzzle of space which yokes them into the same moral universe. When Matisse frames his figures in the blocks of color and then frames toward those windows which are hives of color, he places his figures, at once, in relationship to the exuberant physicality of this world, the unknowable other, and perhaps the equally mysterious self. A Rufty painting or drawing echoes with these associations.

|

| Eleanor Rufty Voice-Over, No. 7, 1995 Gouache 11 x 15 inches |

She has, I think, in these mediations on the figure, defined her own sense of space. If della Francesca’s figures are in relation foremost to God, and Matisse’s are still clearly defined as existing in rooms, Rufty’s exist in relationship to one another on paper or on canvas first and foremost. They exist in relationship to one another formally first, in their scale, the nature of their lines, their colors. The spaces are not physical or temporal or psychological: they are formal space.

Which is not to say that the work is unemotional. In fact, it’s rich in emotion, but it’s also rich in doubt. I would say that formally the paintings and drawings seem to be asking how to construct figures after the Renaissance, after Matisse; and that question does lead us back to the world. Why can’t the artist just plop an odalisque onto a couch and be done with it? I would suspect it is because everything is suspect: narrative, psychology, the nature of painting. Everything is up for grabs in a way that it was decidedly not when Piero della Francesca was painting.

|

| Eleanor Rufty Voice-Over, No. 11, 1996 Gouache 22 x 30 inches |

Maybe that woman is readying herself for a cocktail party. But, maybe it’s a funeral. Maybe she’s just stepping out for a quart of milk. Maybe that other woman is her mother. Maybe she’s an aunt. Maybe she’s a flicker of memory, someone the woman checking herself in the mirror saw on the bus. There is no reason, spatially, to even suppose that these figures exist simultaneously in time. They only exist in the here and now of our experience of a drawing because the artist has forced them together. Even when the work could be read autobiographically—it’s hard not to interpret one recurring figure of a woman as either the artist or some psychological stand-in—what do we actually learn, autobiographically, about the artist? Nothing. But Rufty’s figures, at once iconic and specific in their rendering, do carry enormous suggestions of rich interior lives. But their lives remind mysterious in the way that people are always mysterious. That, for me, is the triumph of the work. It isn’t so much that the stories or character have been explicated, but that the mystery of those stories and people has had a grave light cast upon it. That seems like more than enough and I am content to do without narratives and simple psychologizing in exchange for this more complicated truth. ![]()