print preview

print previewback REBECCA POYNOR

Review | Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens by Corey Van Landingham

Tupelo Press, 2022

|

“Darling, we are such sweet modern machines,” Corey Van Landingham writes in “Desiderata,” the poem that opens Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens, her second collection of poetry. To confront this statement, Van Landingham meets themes of history, art, and mythology with an unflinching, contemporary gaze and adeptly transforms these abstract and timeless considerations as she braids them into contemporary drones and smart phones. History, art, and humans, too, are drafted into the distance and violence that have emerged to accompany novel forms of technology.

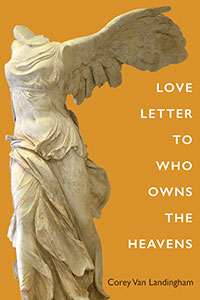

In the poem “Love Letter to Nike Alighting on a Warship,” Van Landingham’s speaker addresses Nike, the Greek goddess of victory (whose representation also adorns the cover of the book). In this sonnet, Van Landingham incorporates figures from both art and mythology—seamlessly invoking Rilke, Apollo, and Dickinson within the tight boundaries of fourteen lines. Art meets violence and itself becomes technological as the poem tracks the sculpture of Nike taking on comparison to a drone. Van Landingham begins the poem:

I could not know how like the drone you would become,

standing below your grandeur at the Louvre.Ears stripped, mouthless—Good Girl! Broken Goddess!

You were already, were still, the woman commemoratinga long war.

Nike, goddess of victory as she is, enters our moment through not only the connection to the drone but also through the speaker’s own connection to her—and to the poet’s use of the continuous “were still.” Nike still faces us as the woman, the girl, the goddess—and she shows no signs of leaving her post or pedestal. In fact, the speaker enlists poetry into the same comparison to violence. Later in the poem, Van Landingham writes, “Poetry and war, senseless.”

Mythology persistently aims to become technological throughout the book. In “Love Letter to Nike Alighting on a Warship,” this effect is often achieved as, repeatedly, mythology becomes the drone. However, there is symmetry in this transformation. The drone, too, becomes mythological.

In “Bad Intelligence,” a poem situated later in the book, Van Landingham tells of the naming of a drone after the Greek word herma as the speaker asks of the old gods: “give us the full leaked report without seeking // permission for entry. Hermes, you who protect / trade and travelers. God of transition, and poets.”

Van Landingham’s speaker joins art and history in their state of mechanical being—sentient and human but trapped within modern machinations and technology. Though the speaker often merges with technology, she never feels less human. Perhaps, in fact, it is the unflinching honesty about her relationship with virtual spaces that makes this speaker feel so distinct, so personal.

Also threaded throughout this collection is the narrative of a long-distance relationship. This relationship, often marked by the distance between the two figures, is defined in a nearly completely digital space, and the couple in the relationship become a bit digital too. Despite the physical distance between the speaker and her lover, the relationship remains distinctly intimate and sexual. In “Elegy for the Sext,” the first part of a triptych that makes up a section of the collection, Van Landingham writes, “I imagine the pixel as a tactile thing. A being capable of touching / another, in passing, for even the shortest period of time.”

The speaker and her lover communicate on phones and computers, by FaceTime and through texts. Intimacy and closeness exist inside of selfies and sexting, and thus shed a bit of their human connection. The speaker sees her face reflected back in cell phone screens, sends sensual photos to her lover, and recreates the body as “a downloadable thing.” The relationship is inside the phone, and so the speaker, to a degree, is too. In “FaceTime,” Van Landingham writes:

Instead, you reach

the phone outside

your top floor apartmentand dangle me, face-down,

above the street.

The phone is what is being reached outside of the subject’s apartment, but it is the speaker herself who is dangled face-down above the street.

Though there is intimacy in these virtual interactions, the status of the virtual indicates a level of distance between the two lovers. To the two members of this relationship, and to much of the modern population, the cell phone is a necessity. In “Taking Down the Bridge,” Van Landingham touches on this need:

“Imagine, I wanted to tell you,

what of us, a century from now,

they will haul in to hold—

your ancient, hulking cell phone

that could be a paper weight,

a time machine,

a device for measuring love.”

What is so interesting about this moment is not simply the need for the cell phone inside this modern love story, but the acknowledgement of technology as a decaying thing—how this technology as well as the current conception of humanity will soon become relics. The poem echoes Ezra Pound to ask, “Why must we make / everything new?”

Though the speaker is connected to technology and often becomes it, she is also distinctly aware that it will become, to a degree, obsolete, and the rest of the present with it. Humans desire change, and the speaker is all too aware of both the change and the desire. Though the book joins past to present, there seems to be a disconnect—a distance—between now and a vague future.

It seems that, for the speaker, the future will only be connected to the present in retrospect. Just as we now are drawn to history, humans of the future will be drawn to us—their own history. Van Landingham links her speakers to the past through art and historical fact, and the figures of the future will be tied to the present in that same way.

In the poem “Cyclorama,” a long, sectioned poem that appears alongside “Elegy for the Sext” and “Field Trip” as the second part of the triptych, Van Landingham remarks, “The problem might be that art outlasts us. That it casts us for a future eye.” Just as Van Landingham’s speaker observes the past through art, she is aware that she, too, will one day be observed by the future. And perhaps not in a wholly forgiving light.

Concerns of distance wind throughout this collection—not just between the two lovers or between the present and future but also within the distance from both the self, the body, and others that is characteristic of our present-day world. This conceit is first introduced by the title of the book, a self-proclaimed love letter, as well as the other love letter poems scattered throughout the collection. Though “love” implies a certain closeness, the speaker is still writing from a distance. These poems are letters, after all, and their subjects are not physically present inside the poems.

In the later love letter “Love Letter to MQ-1C Gray Eagle,” a poem in the final section of the book, Van Landingham dexterously explores this conundrum, balancing both the closeness with technology and the inherent distance from humanity within it. Many of the themes of the collection seem to fuse together here, and the speaker and technology become even more directly bonded. Though the technology has been a present factor in the long-distance relationship, it has seemed to operate as almost a lens through which the speaker and her lover see one another.

But the machine is not a lens or a window; it is a watching eye, and Van Landingham addresses the speaker’s relationship to the machine as an intimate thing:

Because of you, when my arms are upraised to the sky,

they are also appraised. Show me my worth, drone,

in the back ally, hidden from every eye but yours.My metalcraft, my no-see-um, my I-dare-you-to-come-

down-from-there—if you require no hands and I require no

privacy, aren’t we destined to be less human together in the dark?

Here, the machine is directly addressed as a present and active figure in the speaker’s life. The machines have been watching the speaker and she knows it. Unflinchingly, the speaker watches back, and neither are entirely human.

The book ends on another love letter as “Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens” pairs the historical world we have known before the machines with the possibly collapsing future. Though the machines are, of course, present in this poem, their presence is here notably, and for the first time, independent from the speaker. In this epilogue poem, machines and violent men own the sky, but they are unexpectedly set apart from the speaker. Their presence becomes suddenly separate. Van Landingham writes:

I’ll remember a time when

men were the ones doing harm withtheir own hands. I’ll remember the words I once

had to give to you, on the porch, in private.

Van Landingham leaves us in an intimate moment between the speaker and the subject of the final love letter. But yet, the speaker does not receive the absolute privacy that she seems to believe she has attained. Like the machines, the reader, after all, still watches. ![]()

Contributor’s notes: Rebecca Poynor

Contributor’s notes: Corey Van Landingham