CAITLIN HORROCKS | It Looks Like This

|

Mrs. Holtz:

I know this was a favor, like extra-extra credit, but if you give anyone else this assignment, maybe you could just let them retake the Hamlet midterm? You said you wanted to make this easy for me, that all I had to do was write a long paper about my life, about my mom and my sister and my friends, about where I live and what I do, and you’d give me credit for completing your English class. I really appreciate it, but I thought I should tell you that this wasn’t all that easy. Not knowing what to say about Hamlet is one thing, but this was embarrassing, you telling me to just write what I know and me still not knowing how to go about it, what to say. I tried to use topic sentences. You said you’d show the paper around if I did a good job, try to talk my other teachers into giving me credit for their classes the semester I left, so I tried to put some math and science and stuff in for them. Fifteen to twenty pages is a lot, so I used some pictures. I hope that’s okay. This was really hard for me, for a lot of reasons.

I. This is where I live: |

|

|

‹— Waterford, Ohio

|

|

|

|

In the paper the other day, some guy said, “Based primarily on the strength of

local tourism, Ohio’s rural communities are sinking or swimming.” My mom’s the one who read it out to me, and she said, “Sinking or swimming? This fucking town was built underwater.” I hope it’s okay to put that. My mom’s pretty foul-mouthed. She’s been swearing more the sicker she gets. Now that she can’t really manage the stairs, she’s totally obscene. What’s happening to her is obscene, she says.

Maybe you could show this first part to Mrs. Steiner and Mr. Kincaid? My last semester I was taking Geography and Civics. They might like to see that I use maps and that sometimes I follow what’s in the paper. I’m writing this at the library in Mount Vernon, and when the librarian asked what I was doing, I said I was writing a report, but with pictures. She said I had to cite some of them, like this: <www.mapquest.com>. That’s where I got the maps from.

II. This is my house: |

|

It’s on County Road 54 and it stands out more than you’d think it would because the neighbors are all Amish. The ones to the east of us have always been there, but the ones to the west just moved in from Pennsylvania because the land’s cheaper here. They cut off the electricity and dumped the kitchen appliances out in the yard. I’m tempted to ask if I can take the oven, because it looks newer than ours, but they’re all so unfriendly. Besides, I’m not sure how I’d haul it inside.

It’s an old farmhouse, but we never did much with it apart from a kitchen garden, a |

| |

|

|

few chickens. The roosters are sons-of-bitches, and that’s not what my mom says, that’s what I say, because I’m the one has to go into the yard to feed them and they’re trying to peck me to death. I have marks all up and down my legs. I’m looking forward to picking one out and eating it.

We knew it was coming, with my mom, and I said she should pick upstairs or downstairs, so we’d be ready when she couldn’t go between anymore. I said if she picked downstairs we’d make do with the half-bath, but I was happy she picked Up. I have to help her wash now either way, but for a few months I could just get her settled in the tub and she could take care of herself. Now it’s harder.

Since I mentioned them, here are the chickens |

|

And here is a tomato plant from the garden: And here is a tomato plant from the garden: |

|

|

| I told my mom about your extra-credit idea, and she said to bring you tomatoes and zucchini from the garden when I bring this paper to you. I’ll bring the tomatoes if they’re ripe but I’m embarrassed to bring the zucchini. Everybody’s got it coming |

| |

|

|

out their ears this time of year and giving it to someone just makes it look like you’re trying to get rid of it. But I thought I should tell you that my mom said to bring you some, and that she said you’re being very generous and that I should make sure you know that I appreciate it.

III. My best friends are Dana Linfield and Jess Berman. We sat in the back left corner, by the windows, in your American Lit class last year. They come by sometimes, but we don’t have the same things to talk about anymore, so we just talk about old stuff, which gets boring. Plus it’s hard for me to enjoy it when other people are at the house because I know that my mom’s always waiting for them to leave. Dana’s going to the Nazarene college in Vernon and Jess answers the phone at a dentist’s office in Zanesville. Here they are:

friends |

|

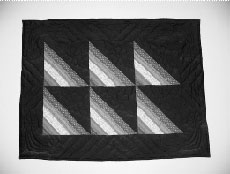

| You wouldn’t know Elsa, and I don’t have a picture of her. I think we might be friends, but it’s hard to tell. I don’t think she’d say no to a picture, if I asked, because she’s not really backwards, like she’d think a camera was going to steal her soul. I just don’t know how I’d ask her. Since I don’t have a picture of her, here is one of her quilts: |

|

|

|

I met her at the fabric store in Danville. Her husband brought her in their buggy. Elsa and I were inside looking out to the street when he tied their horse to a fire hydrant. I could hear her sigh and it made me like her. She’s only a little older than I am, I think, but she has two kids. She does beautiful work. The fabric store always had some traditional pieces on display, but I hadn’t realized they were hers until that day. She walked up to the counter and started unwrapping a puffy package, cut-up brown paper grocery bags tied with twine. It was just a Churn Dash, queen sized, but done tiny, all by hand, the littlest pieces an inch square. “God,” I said. “You’ll go blind,” which on one hand was an all-wrong thing to say to an Amish person, but on the other hand, you learn growing up around here that the Amish don’t talk to anybody else anyway, so in a way it doesn’t matter what you say to them. Elsa spoke to me, though. “Haven’t yet,” she said. “Don’t intend to.”

“I’ve had people asking after you,” Mrs. Carpenter said. She runs the fabric store, and for a moment I thought she was talking to me, but it was to Elsa. “Up from Columbus for the day, antiquing. One of them owns a gallery on the Short North.”

Elsa didn’t say anything, just looked at Mrs. Carpenter. The look reminded me of how as a kid all the Amish on market days made me sad, because you could see how easily they smiled at each other but never at you, and I didn’t understand what would be so wrong with me that I couldn’t be smiled at.

“They asked who had done the Ohio Star in the window, and the Bear’s Paw and the Trip-Around-the-World up on the wall. They asked me to take them down and match the stitching against the yardstick on the cutting table. Ten stitches per inch, they said, you don’t see that much anymore. Is the whole thing by hand, they asked. And I said, absolutely, Elsa Beiler’s Old Order, a real craftswoman. Lady said she’d be happy to carry pieces like these, and she knew someone with a traditional furniture shop in Olentangy who’s looking for pieces to drape on bench backs, that kind of thing. She said you should bring some work by, since there was no way to call you.”

“Wouldn’t be much of any way for me to bring things by, either,” Elsa said. |

| |

|

|

“Do you know anyone who could give you a ride?”

“I’d do it,” I said. “I could take you.”

They both looked at me. “Do I know you?” Elsa asked.

“No.”

“Then I would pay you,” she said, after a few moments thinking about it. “It would be a help.”

“I’d be happy to,” I said, and I was, maybe because she wore black sneakers with her navy blue dress, or because she spoke to me, or because it was a thing I could do that would get me out of the house and after eighteen years growing up around people who wouldn’t speak to me, I thought it would be nice to have one in my car for awhile to talk to. We picked a day and a time, and she gave me directions to her farm, and when I got there it looked just like she’d said. It looked like this:

Every three weeks I drive to her farm to pick her up. I drive up to the house, and she comes down the porch steps. She’s always waiting on the porch. She’s never had me inside and it keeps me uncertain if we’re friends, or just friendly with each other. |

|

|

|

I turn the car around, then it’s twenty miles on 229 to the Interstate, then forty minutes on 71 to this fancy Amish furniture shop in Olentangy, then another half hour to the gallery in the city. People stare at her in Columbus, at her long dress and her hair pulled back hard under her bonnet, and I forget that I shouldn’t be startled by it.

Elsa always has at least one new piece for each place, crib quilts and wall-hangings, small pieces to fill demand. Full-size bed quilts take too long. Still, she must spend hours every day away from the kitchen, or her children, or the garden, or whatever else she’s supposed to be responsible for, to produce that much work. I wonder what her husband thinks, what the other women think. In the car she talks about how in the autumn her hands are quick with a certain light, how they shake with the work inside them, and the only way she’s found to calm them is to choose colors, cut pieces, load stitches on the needle. When she talks that way it’s the only time I feel sorry for her, but then I’m sorrier because it makes me happy to know that that’s something I have that she doesn’t, that if I ever wanted or found the time I could draw or dance or listen to music or just drive too fast with my window open and Elsa can’t do any of those things. I didn’t think she could have any music, either, until she told me she met her husband singing.

“It’s just instruments we can’t play,” she said. “The teenagers have sings on Sunday evenings.”

“Sing something for me,” I told her.

“They’re all hymns.”

“Sing one anyway.”

“I can’t.”

“Why not?” |

|

|

|

“I’m married now. I can’t sing anymore.”

“That’s sad,” I said.

“Why? The sings are for courting.”

“It’s sad you had to stop.”

“Why should I care what makes you sad?” she said.

The more I think about it, the more I think that Elsa won’t let us be friends after all, and that’s one more thing that makes me sad so then I stop thinking about it.

IV. I have a job. I make quilts too, like Elsa, but they’re not as good:

If I sold this one as my work, produced in the year 2006, handquilted at four to five irregular stitches per inch, some of the angles on the quilt top crooked and a few of the seams lumpy, it might bring $250 at Buried Treasures, in Martinsberg, $300 if it sold at Annie’s Antiques, in Jelloway, $325 at the Treasure Mart in Danville. I’m |

|

|

|

not nearly as good as Elsa, and I’m definitely not Amish, which doesn’t help in the quilt business. $250 minus $60 for fabrics, batting, and thread, divided by 150 hours of work, equals $1.27 per hour. This is why I don’t sell my quilts as made by me.

To get technical for a minute, this quilt, with the crooked angles and the lazy handstitching, was machine pieced out of salvaged, distressed, printed cottons, on an 1886 Singer treadle, filled with flat, all-cotton batting, and quilted with a size 7/9 needle using unwaxed thread. The pattern (Log Cabin: Barn Raising) was popular in northern Ohio from 1865 to 1895, and if I told you that’s when this quilt was made, you’d have to know a fair bit about quilts to be able to prove me wrong. Antique

quilts go for a lot—$500 minimum anywhere in Knox County, more in Columbus, but I’m scared to try and show in Columbus because the appraisers there know what they’re doing.

I’m not sorry or anything. $500 minus $60 divided by 150 is still $2.93 an hour. I could do better driving to the Wal-Mart in Vernon, but I can’t work outside the house because of my mom. She taught me to quilt years ago. I’ve always done it by myself. Quilting circles seem like a dumb idea. I don’t want to sit around and listen to people bellyache. My problems are mine. No one else’s. I’ve never really liked quilting all that much.

V. Please show Mr. Martin that I do math everyday now, more than I did when I was in his class. On my last sale, a double-size Dresden Fan, my hourly worked out to $3.438, but I remembered that when the last number is five or more, you’re supposed to round up, and that makes it $3.44. I used a calculator, but please tell Mr. Martin anyway, and that I’m sorry I never understood logarithms. Also, maybe, that quilting takes a lot of geometry, and that I still remember that the Pythagorean Theorem goes like this:

|

|

a2 + b2 = c2 a2 + b2 = c2 |

|

|

| VI. This is my older sister, Melie: |

|

|

|

She’s 22, four years older than me. She’s the pretty one, not that I think I’m ugly or anything, just that it’s true, she’s prettier. After she finished high school she left Mom and me in the house to move in with her boyfriend in Vernon. She’s still living there with a guy, but I don’t know if it’s someone I’ve met. I lose track of who she’s seeing. She still comes around sometimes and after she leaves Mom says, “If I’m not a grandmother yet, it’s not for lack of Melie trying.” I don’t tell her that Melie could have made her a grandmother three times over, that I know of. Twice she asked me to take her to the clinic, all the way into Columbus, because she said people might recognize her in Vernon. I said if they did, they wouldn’t find out anything they didn’t already know about her. So the next time she had a friend take

her, and I found out anyway, which goes to show that I was right all along. I don’t know why the men don’t take her. I don’t know why she isn’t more careful in the first place. I asked her once and she said what did I know, I’d never been with anybody and I acted like I never wanted to. “My heart’s bigger than yours,” she said. “You’ve got a skinny little heart inside.”

VII. I don’t have a picture of my mom. She wouldn’t let me take one, but you can picture her kind of like Melie and I mixed up together except older, of course. She’s got brown eyes and blonde hair that used to be really long until she had me cut it a couple of months ago. I could tell she was sorry to cut it, but she was sorrier to need me to brush it for her, and tie it back, and this way probably works out better for the both of us. |

|

|

|

Her hands got bad first, just hurting her and then hurting her so bad they got twisted up. Then her feet and her ankles did the same thing. The anti-inflammatories don’t work the way they’re supposed to for her. The doctors don’t know why. She can’t use her hands at all anymore, so I turn the TV on in the morning for her and turn it off at night. She can kind of use the remote control, but not so well, and she gets mad when she can’t watch what she wants to. Her hands look like this:

|

|

|

|

| but those aren’t her real hands. Here’s the citation: <www.bret.org.uk/nec5a.htm> |

VIII. Please tell Mr. Kincaid from Civics and US History that I remember that William Henry Harrison, who looked like this: |

|

<http://www.bartleby.com/124/pres26.html>, served the <http://www.bartleby.com/124/pres26.html>, served the |

shortest term of any president because he gave a long boring speech in the rain, caught pneumonia and died, and that the moral of the story is that we should keep it short. I remember that Gettysburg was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War but Antietam was the bloodiest day. I remember about how Manifest Destiny was both good and bad because the West was settled but lots of Indians died. I remember that Waterford was founded in 1841. I remember that in 1905, when the trains still ran, a |

|

|

|

boy died on the trestle bridge near Gambier because his own father tied him down. I remember that our river is the longest in Knox County, that it is called the Kokosing and that this is an Indian word that means Owl Creek. Tell Mr. Kincaid that even when I’m on 71, heading home from the gallery in Columbus, and all I want to do is stay on the Interstate until it dumps me into Lake Erie, I think of it as our river.

IX. I thought about what I could put here for Mr. Samson, but I honestly don’t do any physics. Not that I know of anyway, and I didn’t understand it so well when we were learning it. I remember that gravity equals 9.8 meters over seconds squared, and that when something’s falling as fast as it can possibly fall, that’s called terminal velocity. Maybe you could tell him that I know about biology, even if I don’t know physics. Like this: Kings Play Cards On Fat Green Stools: Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species.

X. Once in the car I told Elsa about my mom, about how she was sick. We talked about it a bit and then Elsa asked me if my mom had a relationship with God. It was the only time Elsa has ever mentioned God to me. She said maybe it would ease her pain. I asked my mom about it that night, even though I knew it was a bad idea. “He’s been fucking me over, if that counts,” my mom said. “What’s wrong with you?”

I want to tell Elsa what she said, but I’m worried I’ll shock her, even though I’ve never seen Elsa shocked. I wonder if she’d have some suggestion, something I should say to my mom next, about God, or about Him having a plan, or about how things turn out okay in the end, or about not fighting so hard. I think of what Elsa could say to me, and I want to hear it from her, even if He doesn’t, and things won’t, and what else does my mom have left to do? Even if none of it’s true, it would be nice to hear it from her, and believe it for awhile, just as long as it takes to drive from Columbus back to her farm, and have it sound like a thing a friend would say to me, to have it sound like comfort.

XI. I think it was pretty soon after that that I saw you at the Kroger, in the aisle with |

|

|

|

all the cereals. You were buying Lucky Charms and it reminded me to ask about your kids. Then you asked about me, and you said it was a shame that I’d had to leave high school without finishing my last semester, when my mom got bad, and I said I guess, although I don’t know what I’d do with a diploma anyway, since I’m not headed for college and I can’t look for a job outside the house. And you said it would be a nice thing to have, it would just be an important, nice thing for me to have done. And then you told me to write this paper, you told me that you’d see what you could do.

I’m not telling you this because I think you’ve forgotten about it, but because it was a nice thing to have happen, it was just a kind idea for you to have had, and even if this paper doesn’t turn out to be good enough, I wanted to say thank you.

XII. I’ve realized that I know lots more about biology. I know that my mom’s hands are messed up because her synovium is swollen, which is the name for the lining around her joints. Her cells divide and divide and thicken the synovium and that’s called pannus, and those cells release enzymes that eat bone and cartilage. I don’t know if that has a name, but it means that her hands don’t have the right shape anymore, because they’re being digested from the inside, and even if the anti-inflammatories started working and she was in less pain, she’ll never be able to use her fingers. I read somewhere, too, that pain travels through the body at exactly 350 feet per second, and for a long time I pictured the pain running from my mom’s joints to her brain, over and over, racing with itself. Then I realized that the pain doesn’t travel so much anymore as live there. It’s settled on in, it’s farming her bones, and it doesn’t need to travel because it’s never going anywhere.

I know that early-onset rheumatoid arthritis doesn’t kill anybody, you just get older and your joints get more digested and there’s nothing anybody can do for you. My mom’s 45. She says: “I wish I had something that would kill me, sooner or later.” I said, “Don’t say that,” and she said “Wouldn’t you, too? Or do you want to spend the next thirty years helping me off the toilet?” And of course I don’t but I can’t ever, ever say that to her.

|

|

|

|

XIV. The other day I showed up at Elsa’s house to pick her up and she was waiting on the porch, like always, but her arms were empty. She waved me out of the car and up the steps and it was exciting, the feel of the wood stairs under my feet, even though they’re just steps and just wood and I know they’re not really any different from porch steps anywhere else. “I don’t have anything finished this week,” she said. “Nothing for the shops.”

I almost said, “You could have called me,” before I remembered that she couldn’t. So I said: “That’s okay,” and asked if I should come back in another three weeks.

“I’m sorry you came all this way,” she said, and I said I didn’t mind. “Would you stay for some iced tea?” she asked. “Something to eat?” and I said I’d love to.

It was a nice day, sunny but not too hot, so it didn’t feel strange that Elsa didn’t invite me inside the house. I waited on the porch and in a few minutes she came back out with two blue plates, glasses of ice tea balanced beside pieces of pie. The tea was kind of warm, no ice, and the pie was blueberry. We both sat on the porch railing, Elsa’s skirt hitched up a bit, the forks clinking on the plates as we ate.

Please tell Mrs. Yarnell that I remember what she said in Life Skills/Home Economics about the Amish not keeping their kitchens clean the way a modern person would, and how we shouldn’t buy their baking on market days if we valued our lives, but that I valued eating Elsa’s pie on her porch along with my life and it’s important to be polite. And also that the pie didn’t make me sick or anything and that if Mrs. Yarnell could see the state of my kitchen at home she’d know it wasn’t my place to be refusing anybody’s pie.

I told Elsa the pie was good and she nodded at me. Every so often you could hear kids laughing inside the house, grasshoppers clicking in the yard. A fly kept trying to settle on the rim of my plate. Elsa stayed quiet until I was done eating and then she said, “You’ll be all right.”

|

|

|

|

“What?”

“You’ll be all right. Even if it doesn’t seem so, sometimes. You’re going to be fine.”

“Everybody says that.”

“Like who?”

“Like my friends. My mom’s doctors. My English teacher.”

“That doesn’t make it untrue.”

“It’s just a thing people say. They don’t see how things will possibly turn out okay but they want you to think they believe in you. That they believe that things will.”

“It doesn’t mean anything to me, whether you think I believe in you or not. Believe in you, what does that mean? You’re not a ghost. You ate my pie.”

“Sorry.”

“For what? Eating my pie or being a fool? You’re built for swimming,” she said. “That’s all I meant. You can believe as not whether God made you that way as long as you know you’re not built to sink. You’ll swim in this life if you want to, and if everyone keeps telling you so it’s because they can see you’ve got fins. And a strong tail. And a mouth like this,” she said, and pursed up her lips and went glub-glub like a fish and I laughed. It was the first nice thing and the first joke she’s told me, all at once, and the first pie and the first time talking on her porch and I have hopes for seconds. Sometimes while I’m making dinner or piecing a quilt or writing this paper I just sit and know that Elsa thinks I’m a fish, and that things turn out all right for all the swimming things in the world.

XV. That just made me remember one more thing that Mr. Samson might like to read about. He taught us a lot about marine biology, so he might like to know that if I had |

|

|

|

the time to make any quilt I wanted, I would do a whole-cloth, the top all one color so if you saw it on a bed somewhere, you would think, how boring. But when you got up close, you’d see the trapunto stitching, the quilt top covered with animals in silver thread, one of everything that lives in the sea. Eels like snakes and the kind of jellyfish with tentacles that stretch for miles. Octopuses and giant squids, sharks and whales and coral and anemones and the kind of fish that live down where it’s dark and have lanterns in front of their faces. I’d go to the library in Vernon and find pictures of everything, so I’d know what they all look like. I’d stitch made-up things, too, so there would be sea monsters and mermaids and sirens and kelpies. I’d like to put in Mimic Octopuses, too, but I’d have to figure out how because what’s special about them is that they can look like anything. The quilt would be thick with everything I could picture, hundreds of secret creatures I’ll never see for real. But only up close. From far away, it wouldn’t look like anything, it’d just look like this: |

|

|

Contributor’s

notes

return to top

|