EMILY SMITH | Reinstallation, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #541

In 1967 Sol LeWitt wrote, “In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” In part as a response to the overt subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism, conceptual art moved towards more objective modes of making art.

|

Sol LeWitt |

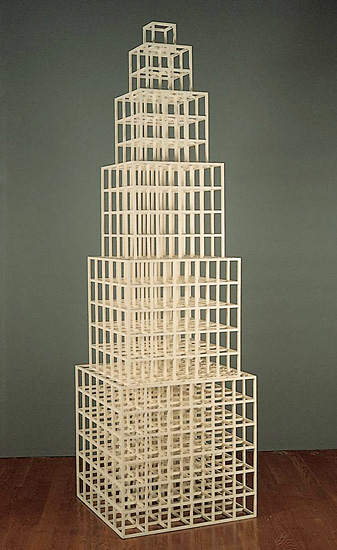

For LeWitt, this involved devising systems to generate artworks, as evident in the open cube sculpture above, 1 2 3 4 5 6, where predetermined mathematical equations dictate the sequence and composition. From top to bottom, the equations 1 x 1, 2 x 2, 3 x 3, 4 x 4, 5 x 5, and 6 x 6 establish the number of cubes for each tier.

In 1999, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts acquired LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #541, a sequence of four isometric cubes, and installed it the following year outside the Sydney and Frances Lewis Galleries of Modern and Contemporary Art.

|

Sol LeWitt |

|

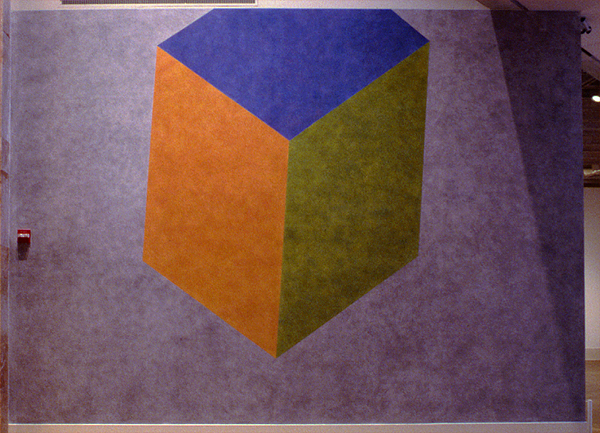

2000 VMFA installation of Wall Drawing #541 |

The wall drawings, which LeWitt began creating in 1968, emphasize LeWitt’s interest in a systematic, objective approach to art-making. For the wall drawings, the idea lies in the instructions devised by LeWitt. For example, plans for one early work read: “with pencil, draw 1000 random straight lines, 10 inches long, each day for 10 days, in a 10 x 10 foot square.” Once conceived and written by the artist, these instructions can be executed by anyone.

|

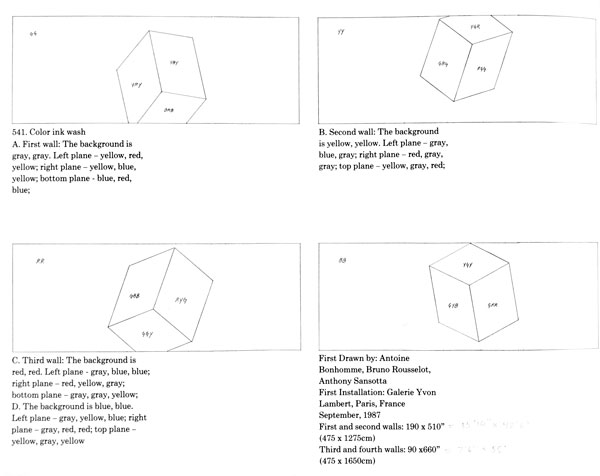

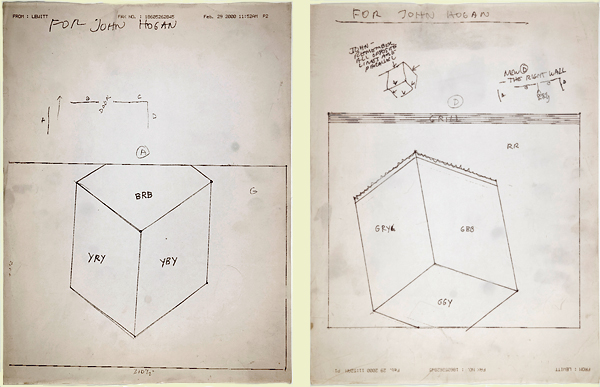

The original diagram for Wall Drawing #541 |

|

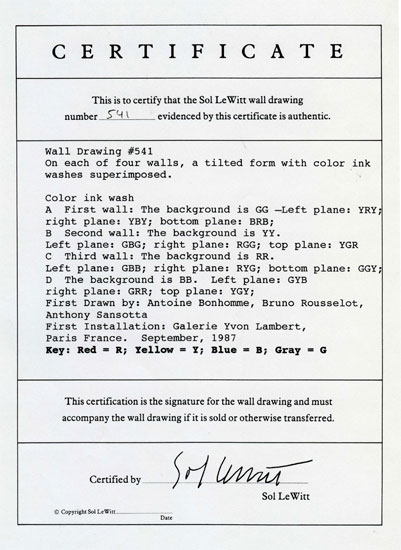

VMFA’s certificate of authenticity. |

|

An example of Sol LeWitt’s drawings for the 2000 installation of Wall Drawing #541 at VMFA. |

To that, when an organization or individual buys a LeWitt wall drawing, they receive two things, neither of which is the finished work of art. They get a certificate of authenticity and a detailed set of instructions—that is, they get the idea. To install the piece, they worked directly with LeWitt and now, since his death in 2007, work with LeWitt’s estate to hire one of his trained draftspeople to lead the installation. Above is the original diagram for Wall Drawing #541, which outlines the color schemes, VMFA’s certificate, and some of LeWitt’s drawings that he made specifically for VMFA’s installation and sent by fax.

These drawings involve some adjustments from the original 1987 installation. On occasion, LeWitt made changes to certain wall drawings’ plans to allow for the particulars of spaces, allowing for subjective decisions within his process.

The following images demonstrate one of the adjustments made by LeWitt. First, we see a finished detail of one wall from the original 1987 installation of Wall Drawing #541 at Galerie Yves Lambert in Paris and next, a detail of the same wall from the 2000 installation at VMFA. In the 1987 wall drawing, LeWitt placed the cube at the bottom of the wall, with its top corner pointing upward and the bottom face visible to the viewer. For VMFA’s 2000 installation, LeWitt moved the cube to the top of the wall, shifted the cube downward on its vertical axis so that now we see the top face. No further changes were made to the placement or dimensions of any of the cubes in the 2009 reinstallation—they are identical to those created in 2000.

|

Top: detail from the 1987 installation of Wall Drawing #541 in Paris. |

|

In April 2008, eight years after being installed, Wall Drawing #541 was removed. This was part of VMFA’s ongoing campus-wide expansion project, which included replacement of all of the plywood in the 1985 wing of the museum.

|

April 2008, Wall Drawing #541 is removed |

Above, workers rip away the painted walls. Below, the stack of painted plaster over plywood is all that remained. Though the work in its original state was removed—literally destroyed—LeWitt’s emphasis on the idea over the finished object allowed for, and even anticipated, the destruction of his wall drawings. Furthermore, just as VMFA might loan a painting, sculpture or work on paper from its collection, it may also loan Wall Drawing #541. A borrowing institution receives the right to install the drawing and must contract with LeWitt’s estate to hire a draftsperson to oversee the installation. What’s more, VMFA need not remove the work from its walls, as a wall drawing may exist in two places at once.

|

The remnants of Wall Drawing #541 |

The 2009 Installation Process

|

The 2009 reinstallation team consisted of graduates of Virginia Commonweatlh University's School of the Arts. Clockwise from top left: Anna Bushman, Max Perry, Sarah Watson, John Blatter, Sarah |

Following the installation of new walls in the Lewis galleries, Wall Drawing #541 was reinstalled in January 2009. Because a fundamental component of the wall drawings is that LeWitt need not be present to install, then it did not matter to the outcome of the installation that LeWitt was no longer alive. In a process much like the relationship between a conductor and a group of musicians, a trained LeWitt draftsperson directs a team of workers to create the installation using the instructions as the “score.” Led by Heinemann, the six workers were on site at least eight hours a day, six days a week, for three weeks.

|

LeWitt draftsperson Sarah Heinemann |

|

John Henry Blatter |

|

Clockwise from top left: Anna Bushman, Sarah Heinemann and |

Above, Heinemann completes a measurement at the corner of a cube. It is vital that the dimensions and placement of the cubes are accurately measured—that lines are straight and angles precise.

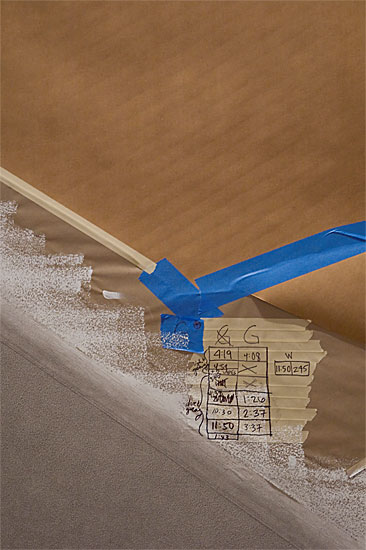

For the next step, the drawn lines of the cube are outlined with tape, which also creates a barrier to which craft paper is affixed. The tape pulls away easily from the wall without removing any paint, thus preserving the clean lines of applied pigment. The craft paper masks the parts of the wall that are not being worked on at that moment.

Next, the wall is repainted with primer to create a smooth surface for the color.

These steps occur separately for each plane within the cube and the background around the cube, so that as one plane is completed, the next is taped off, blocked in with craft paper, primed, and painted.

When Wall Drawing #541 was installed in 2000, color was applied with ink wash. In the years following, the specific brand of ink chosen by LeWitt was discontinued and ultimately, bottled liquid colored ink became obsolete (as architects switched from drafting to CAD). LeWitt and his teams eventually created a similar wash out of acrylic paint. This is what was used in this most recent installation. To maintain the wash consistency, the acrylics are mixed with water in five gallon buckets, with a greater proportion of water to paint. Colors are applied to the walls with soft cotton cloths.

|

Clockwise from top left: Amy Weiks, Anna Bushman and |

Each face of each cube is assigned a combination of colors derived from a palette of red (R), blue (B), yellow (Y), and gray (G). No colors are mixed beforehand. Instead they are applied in layers of pure color. For example, in the photograph above, three workers apply color to the left plane of a cube (the other planes are complete). The diagram for this particular cube determines that the background is BB (blue blue), the top plane of the cube is YGY (yellow gray yellow), the right plane is GRR (gray red red), and the plane that is being painted is GYB (gray yellow blue).

What the diagram does not tell us, but is crucial to the process, is that each letter equals six applications of color. For the plane that is in process, this means that one G equals six applications of grey, the Y equals six applications of yellow and B, six applications of blue. Each side of the cube contains 18 layers of acrylic wash. These layers are applied with a combination of two methods—a pat, or “boom-boom” as it is known amongst LeWitt draftspersons, and a rub. Furthermore, no individual worker is assigned to a single color, or plane, to insure that one person’s “hand” is not evident—another method of refuting signs of personal or individual expression.

|

Time chart for the 2009 reinstallation |

From start to finish, the installation is a carefully choreographed process—from the list of supplies to the application of color. A time chart is maintained, as seen above, to give each layer adequate drying time.

|

LeWitt Installation team |

To keep on schedule, the largest areas, like the background, require all hands on deck, complete with a “ready-set-go” start, so that all workers begin and end at the same time and each application of paint dries evenly.

|

John Hogan |

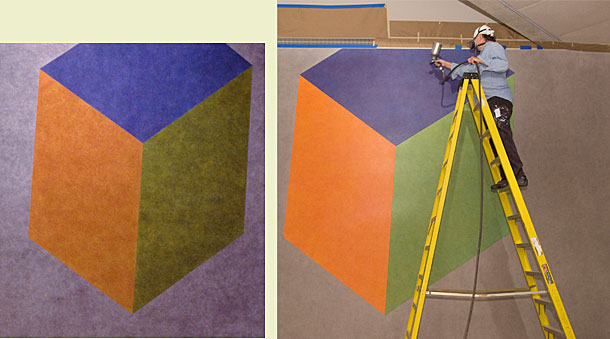

Once all of the layers of color have been applied, the paper and tape have been removed, and final touch-ups have occurred, then a protective layer of varnish is applied. Here John Hogan, another LeWitt draftsperson, sprays a clear, water-based varnish. (Hogan also oversaw the original installation of Wall Drawing #541 at VMFA in 2000.)

|

Left: A detail of Wall A from the 2000 installation

|

To conclude, one of the discoveries of the 2009 installation of Wall Drawing #541 was that the switch from an ink wash to an acrylic wash resulted in overall changes to the color tones, as shown in the images above.

|

Sol LeWitt |

These changes bring us full circle. The switch to acrylic was predetermined prior to the 2009 installation. In keeping with LeWitt’s conceptual principles, the outcome of this switch—the changes in color tone—is a by-product of LeWitt’s systematic approach and continues to give precedence to the idea of the wall drawings over the finished work. ![]()