A Rising of the Wind:

Art from a Time of Rebellion in the Congo

Pende Art and Leadership

The Pende people, numbering more than 500,000 today, have lived in southwestern Congo since the 17th century. They are a relatively decentralized, rural culture with numerous small chiefdoms. Decision-making in a community ideally derives from consensus among adult men, while a chief fulfills symbolic and religious roles, often serving as peacemaker and orator to keep the community united. Pende chiefs are responsible for mediating with the ancestors, whose care from beyond the grave is essential to the well-being of the chiefdom’s kifutshi—the Pende term for the overall environment, including the village and its people, domestic and game animals, farmland, and forest.

|

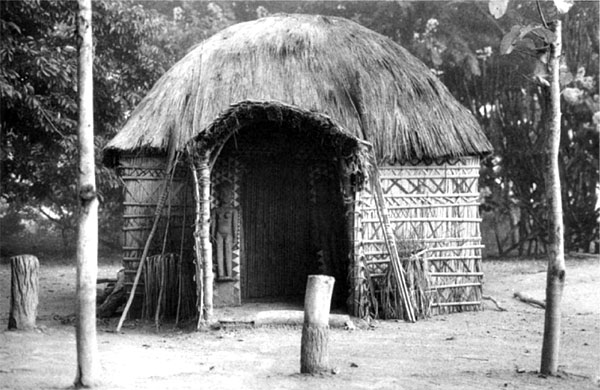

| Ritual House of Chief Kindamba, 1988, showing doorway guardian figures. Photo by Z. S. Strother, 1988. Reproduced courtesy of Z. S. Strother. |

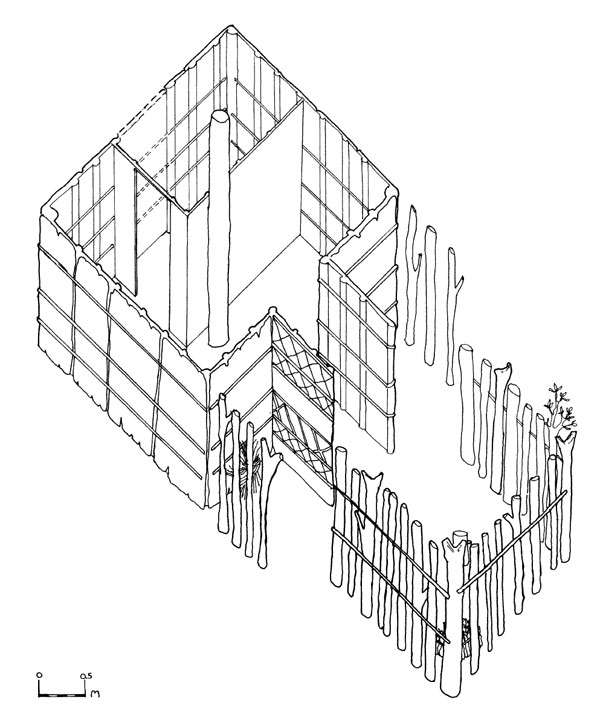

To properly perform this role, a chief must have a special house where rituals are enacted. Its earthen floor is viewed as an altar, and at times the chief sleeps directly on it to facilitate communication with the dead. The house is considered a foyer to the other world and is prescribed to be a square structure with a central pole, the height of which is equal to the length of each side of the house—approximately ten feet.

|

| Ritual House of Chief Nzambi axonometric projection Drawing by Stella Nair from measurements provided by Z. S. Strother. Reproduced courtesy of Z. S. Strother. |

The house must also contain an enclosed back room. Men of the village are responsible for building the ritual house in a single day, starting with a hole in the earth for the central post. The hole is called the stomach of the house, and priests deposit food in it before the pole is inserted. This step is taken to assure the proper maintenance of the chiefdom’s kifutshi, as chief Nzambi’s prayer below illustrates.

| You are the center pole of the house, you are the village with its people, fields, and forest. We have given you seeds for cultivation so that you may grip the earth as the seeds [roots] grip the earth over there. All seeds grow, may you grow [as] the seeds grow, so that the women may give birth, so that the children may give birth, so that there may be a lot of palm wine, so that the hunters may kill [their prey] with their guns. | |

| Prayer by Chief Nzambi, upon erection of a center pole in June 1988, recorded and translated by Zoe S. Strother | |

Though it might seem surprising, the enclosed back room of the house is off-limits to the chief and his family, in effect telling the chief his power is not absolute. Only the priests may enter this space, where the chief’s masks and coffin, certain medicines, and power figures are kept. The mystical power of the medicines and statues serves to protect the chief but also caution him to rule within the limits of his authority, or harm will come to him and his family, especially if he seeks too much power for himself.

The Female Power Figure (below) is an outstanding example of a statue destined for the secluded room in the chief’s ritual house. Noble and sure in her bearing, eyes closed and hands drawn close to her body, possessing a serene inner composure, the image conveys a sense of calm and well being. Pende sculptors deftly manipulate form to create a wide range of expression and character types in figures and masks, and in this work, with a simple elegance, the sculptor has captured a timeless dignity expressive of its protective role.

|

|

|

Female Power Figure, 19th–20th century |

||

Power objects like this were considered potent, and the holes drilled under each arm suggest that the figure might have been manipulated with cords or rods, rather than handled directly by priests. Although the chief and villagers may have seen the statue when it was first made, once it was placed in the rear chamber of the ritual house it remained vivid only in thought and memory. Like the ancestral spirits who cannot be seen but whose presence is sensed in the wind, the statue manifests its impact on the imagination and conscience. In essence, it served as a psychic instrument for both the chief and the community. This sculpture exemplifies classic Pende style, providing a norm that by comparison heightens the unique nature of the statue of the colonial agent.

As the chief’s ritual house illustrates, Pende cosmology encompasses the world of the living on the earth and beneath it the realm inhabited by the dead, who are entrusted with the care of the living. To help a family overcome obstacles in life, the dead sometimes intercede by endowing a chosen individual with special clairvoyance to identify the cause of a problem. However, direct channeling from the dead is rare, so people most often resort to trained diviners for dealing with serious issues. Specialist diviners employ a variety of instruments and methods in sessions that analyze information or testimony in order to determine guilt for a crime or root causes of trouble befalling an individual, family, or community.

The Pende are skeptical toward diviners, who manipulate powerful forces, quite possibly, it is thought, for personal gain. Clients, therefore, might consult several practitioners or, in search of honest and unbiased conditions, seek one in another village or even from a different ethnic group. Hence, competition exists among diviners, and the use of new and flashy instruments indicates that the diviner commands the most recent tools and techniques. One of the more dramatic divination instruments developed during the 20th century was the galukoji, consisting of an accordion-like framework with a small mask on one end.

|

Divination Instrument (Galukoji), early-mid 20th century |

In its collapsed form, the instrument was held in the lap of the diviner, who at a critical moment could operate the frame to make the small mask jump up and face out at the onlookers. The pronounced forehead of the miniature mask implies fearlessness while its rising action might seem in response to supernatural forces. These devices were documented in use from the late 1920s until the early 1950s, roughly the span of the generation that lived through the difficulties of the colonial period and the 1931 rebellion.

Path to Rebellion

At the 1884–85 conference of Western powers convened in Berlin to regulate European colonization of Africa, the Congo Free State was established with King Leopold II of the Belgians as its sovereign. Commercial exploitation of the Congo’s resources was encouraged. In 1908, international pressure stemming from the cruel treatment of the indigenous people caused the Belgian Government to accept responsibility for the “state” as a colony—the Belgian Congo. The profound changes that accompanied this “development” of the Congo thrust the Pende into a new world. Villages and chiefly polities were realigned to suit the colonizers and a head tax was instituted. In 1911, Huileries du Congo Belge, a subsidiary of Lever Brothers (now Unilever), began production of palm oil in the Pende area. The oil had a market for use in soap, cosmetics, paving materials, and margarine. Colonial agents and the operators of Huileries du Congo Belge were harsh, and the two were complicit in coercing Pende men to cut the palm nuts for meager wages—wages that the Pende desperately needed in order to pay the head tax levied by the colonial administration. By redirecting workers away from farming and hunting on their land, the labor of cutting palm nuts resulted in a collateral impact that harmed the nutrition of the Pende. The well-being of the realm—the kifutshi—had been wrenched seriously out of kilter.

With the worldwide depression in 1930, labor conditions deteriorated further. The Pende grew increasingly hostile toward colonial rule because their wages were reduced and their taxes increased, and barbarous treatment at the hands of the colonizers intensified. When labor recruiters went to the villages, men fled into the forest. To force the men back to work, the recruiters rounded up the women, children, and elderly, often chaining them and sometimes abusing the women, until the men relented. For the Pende, it was a deeply distressing and humiliating time. Spiritual movements became more active, and through divination and ritual, chiefs sought assistance from the ancestors, and they believed they saw signs that the ancestors were encouraging them to rebel. Pende cleric Abbé Mupende Musuku Gusimana wa mama recounted that 1931 was extraordinarily windy, which the Pende took to be the response of the ancestors in support of their cause:

That year the dry season was exceptional. The raging wind blew and whistled . . . The spirits of the dead live in the wind, in the whirlwinds. In particular, the whistling of the wind . . . increases faith in the presence of the ancestors who circulate in the wind. The rumor spread that the ancestors were going to intervene to end the inhuman exploitation of the Pende by the Whites. The people’s frenzied imagination took a particular form. The wind rumbled. It was the big trucks which transported the ancestral goods.

—from Gusimana, “La revolte des Bapende in 1931.” Cahiers congolais de la recherché et

du developpement 16: 4 (1970). Translation by Zoe S. Strother

Tensions elevated to a fever pitch in early 1931. The Pende refused to cut palm nuts, their cult activities increased, and they armed themselves with bows and arrows, knives, and machetes. In a confrontation at Kisenzele on May 29, soldiers killed a Pende man and wounded five others. On June 2, Matemo, a Pende man from Kilamba, was severely beaten in an altercation at the Huileries du Congo Belge factory in Bangi. When colonial agent Maximilien Balot was dispatched to collect taxes in the area, as a side task he was asked to investigate why Matemo had confronted a labor recruiter at the factory. On June 8, when Balot entered Kilamba with a small detachment, numerous villagers, led by Matemo, confronted the colonials. During an exchange of verbal threats, a Pende man was injured by a shot and a scuffle ensued in which Balot was killed. Further incidents continued during the following weeks, and by the time the rebellion was suppressed in September at least five hundred and possibly more than a thousand Pende were dead while Balot’s was the only European life lost.

The rebellion came to the attention of the press and public, and there was an outcry in the Belgian Parliament. An inquest was conducted by the president of the colonial court of appeals, who interviewed many witnesses and kept meticulous records. He recommended banishment of several Europeans from the colony for their corrupt practices, he faulted colonial administration, and he laid out recommendations for reforms in colonial and industrial governance. A war tribunal condemned to death several Pende involved in Balot’s killing and ordered prison sentences for others involved in the rebellion.

The Statue of Colonial Agent Balot

The Pende believe that in the face of a formidable adversary, a corpse of the enemy can be used as a protective medicine. Hence, when the colonial detachment in Kilamba scattered out of fear for their lives, the Pende kept Balot’s body. Through the use of torture, colonial authorities ultimately forced its return. At some point, the statue of agent Balot was carved, possibly after the actual body was recovered. Characterized with a menacing glare, the sculpture was created as a weapon that would redirect the agent’s life energy to fight against the Belgians. It is displayed publicly for the first time in this exhibition.

|

|

|

Diviner’s Figure representing Belgian Colonial Officer, Maximilien Balot, 1931 |

||

Maximilien-Norbert Balot (1890–1931) served several times in the Belgian Congo administration between 1913 and 1918 and then again from 1930 until his death in 1931. During the latter term he was assigned to the Kwilu region, where tensions had been building for years between the Pende and the joint overlords—the colonial administration and Huileries du Congo Belge.

The statue of Balot is considered unique in the corpus of Pende sculpture. It might have been kept in the closed chamber of a chief’s ritual house, like the beneficent female figure, or it might have been used by a diviner, or possibly both. Although the specifics will never be fully known, what is certain is the message of the colonial agent’s sculpted form, especially when viewed in comparison with the female figure. Whereas the latter is supple and serene, Balot is rigid and unyielding. His forehead bulges, a Pende convention that expresses lack of self-control. The continuous eyebrow ridge across the face is also a Pende convention, but the eyes are those of an aggressor and are very different from the norm for Pende statuary.

|

| Diviner’s Figure representing Belgian Colonial Officer, Maximilien Balot, 1931 (detail) Pende culture (Democratic Republic of Congo) Wood; Height 24 5/8 in. (62.5 cm.) Lent by Herbert Weiss Photo by Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts |

His glare is fierce. The eyes are wide open and strongly accented by projecting rims and show lots of the white around the pupils—a Pende sign of wrath. Typically, a Pende figure faces straight ahead, the gaze honest and engaging, but Balot looks slightly down and to one side. Although cloaked in the uniform of the ruling colonial administration, in a cowardly way he averts his glance, avoiding direct eye contact with the people. Clearly, this statue is a Pende statement of disgust for the colonial agent and—by extension—for the entire regime.

Over the years, the wooden figure has suffered some deterioration. But the Pende deliberately avoid making statues out of permanent materials, such as stone or metal. A Pende source has said they do not want to make their power objects eternal—that a new chief must have his own figures, and people would be fearful to keep too many spirits around. Thus, in the 1970s, to raise funds for sending village children to school, the statue was offered for sale by the clan that held it and was purchased by the current owner. It is a poignant document of the 1931 rebellion and is one of those rare works where we can trace its story and open wider a chapter in art and history. ![]()

Visions from the Congo is organized by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and curated by Richard B. Woodward, Curator of African Art.

The curator/author wishes to thank Allen C. Davis, Robert and Nancy Nooter, and Herbert Weiss, for their generous loans to A Rising of the Wind, and he extends special appreciation to Zoe S. Strother, Riggio Professor of African Art, Columbia University and Herbert Weiss, Emeritus Professor of Political Science, City University of New York, for their consultation and guidance in developing the project.

Introduction: Visions from the Congo

A Rising of the Wind: Art from a Time of Rebellion in the Congo

Things Man Made: Allison Saar’s Untitled (from the Crossroads installation)

Goddess of Love and Beauty: Renée Stout’s Erzulie Dreams