Mr. Phil May On Himself

from Phil May’s Sketchbook: Fifty Cartoons, 1898

originally appeared in The Sketch, May 29, 1893

| Archives of out-of-copyright material in the creative commons provides Blackbird a chance to rediscover and recommend texts and images from a world of pre-digital publishing | ||

I never had a drawing lesson in my life, but I can’t remember a time when I didn’t draw. At the time of the Franco-German War, when I was a child of three or four, I used to draw imaginary pictures of the battles—bristling bayonets, cannonade, and smoke—more particularly smoke. Later I drew portraits of the actors and actresses who played at Leeds, where I lived. When I was sixteen I made up my mind to come to London, and see whether I couldn’t make a living with my pencil. So I took a ticket, third-class single, and tried my fortune.

It was a hard fight. I had no friends and no introductions worth speaking of. There were comparatively few illustrated papers in those days, and prices ranged very low. I had a good many bad quarters of an hour. Once, I remember, I was in such a desperate mood that I seriously contemplated burgling a coffee-stall—fortunately there was a policeman near, so I did not. But in six months I was beginning to get on. I worked for Society, the Penny Illustrated Paper, the St. Stephen’s Review, and the Pictorial World. In November 1885 I went to Australia to join the staff of the Sydney Bulletin, stayed there three years, and afterwards lived in Paris, until I began my work for the Daily Graphic. Parson and Painter, which helped my reputation a good deal, appeared in St. Stephen’s. It had no effect whatever on the circulation of the paper, and I had no idea that it was going to attract any attention; but when the series was published in volume form 30,000 copies were very quickly sold.

| Many people have the idea that my work is, as they say, “dashed off.” They think that because, when it is finished, there are so few lines in it. But they are wrong. |

||

If a man really has any originality in him it is bound to find its way out. No doubt the art schools turn out plenty of men who can do excellent studies, but they are absolutely incapable of composing good pictures. That is the fault of the men, not of the schools. On the other hand, the man who undergoes no formal training endures many disadvantages. If he loses nothing else, he loses time. There are so many things that don’t come by intuition, but have to be found out. You can find them out in two ways—by being told, or by trying and failing, and then trying again. I have found out a good many things in this latter way, and I don’t recommend it; it is very roundabout. Besides, perspective and anatomy are dull studies, and there is always the temptation not to bother about them beyond a certain point.

|

Many people have the idea that my work is, as they say, “dashed off.” They think that because, when it is finished, there are so few lines in it. But they are wrong. What reputation I have made I ascribe to very careful preparation of my sketches. First of all, I get the rough idea of the picture. Sometimes it is suggested by a story I have heard, or by something I have seen. Sometimes it occurs to me spontaneously.

I sketch a rough outline of the picture I want to draw, and from the general idea of this rough outline I never depart. Then I make several studies from the model in the poses which the picture requires, and re-draw my figures from these studies. The next step is to draw the picture completely, carefully putting in every line necessary to fulness of detail; and the last, to select the particular lines that are essential to the effect I want to produce, and take all the others out. That is how it is done.

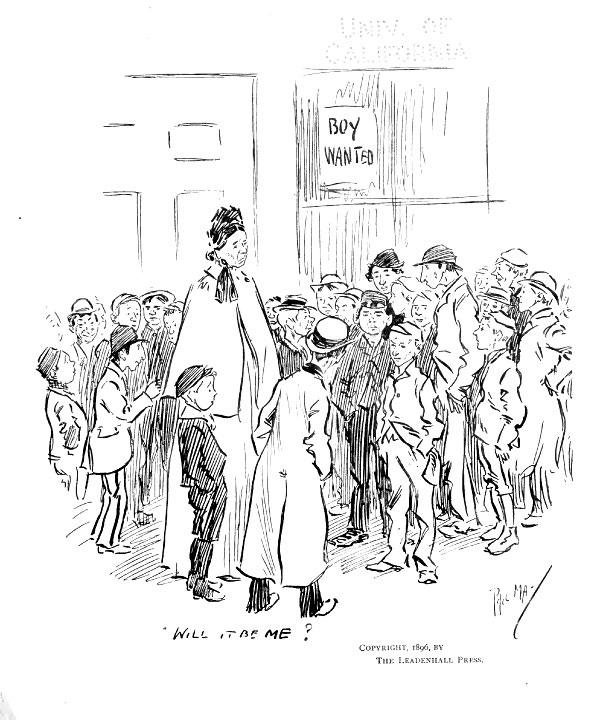

My types are all individuals. I am constantly on the look-out for the individual who embodies a type. When I am drawing a picture with several figures in it I often go out into the street to look for types. But I am collecting them at all times and in all places, more particularly in trains and omnibuses. I collected fifty or so in a recent visit to Battle, and a lot more, of a different sort, when I was on the Riviera last spring. They will all come in useful some day. Australia has supplied me with any number.

|

A quaint old Sydney clergyman

whom I know figured very usefully not so long ago in an allegorical and “up-to-date” presentment of “The Temptation of St. Anthony,” and a well-known Australian

curate was the original of the parson in Parson and Painter.

I am told that

when the book came to be circulated in Greater Britain this gentleman’s sermons

acquired a sudden and enormous popularity, with the result that he unexpectedly

found himself addressing his exhortations to many persons who had previously been

far too negligent of their religious privileges. ![]()

Introduction: Phil May’s 19th Century Drawings and Process

Mr. Phil May on Himself

selections from Gutter-Snipes

Phil May’s Beginnings at St. Stephen’s Review

Table of Figures

Acknowledgments