Incipit Excommunicatio Canina

selections from The Etchingham Letters

Sir Richard Etchingham has returned from India to the family home at Tolcarne where he lives with his daughter Margaret, several dogs, and a cat named Luna. His sister Elizabeth has just left Tolcarne for London with her stepmother, her stepmother’s niece and ward Cynthia, her beloved spaniel Tracy and cat Trelawny. Nephew James (Jem) remains a tutor at Silvertoe College in Oxbridge.

Letters between the humans ensue.

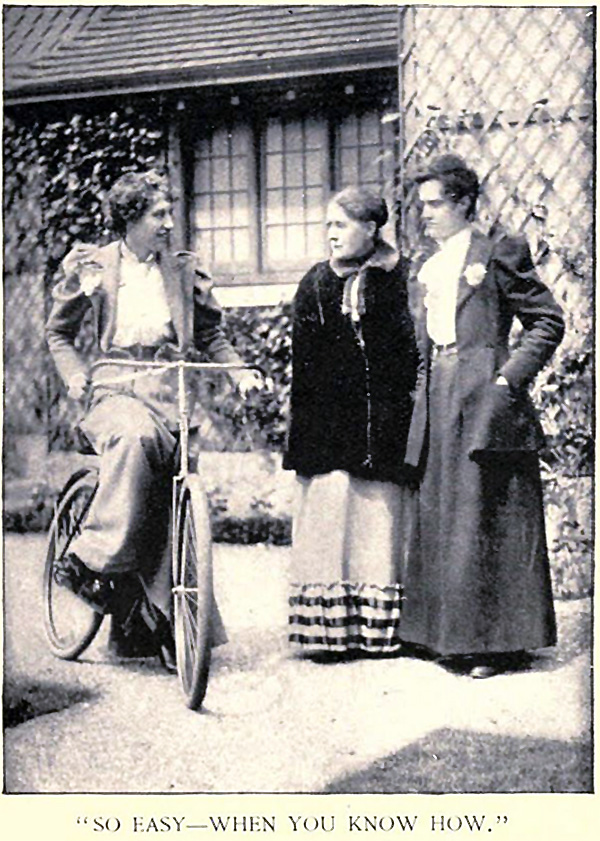

Among the topics and events interwoven in this 1899 epistolary novel, two caught Blackbird’s eye: first, a running attention to dogs and cats—as we are not wholly immune to the charms of either breed (though we, in the words of the novel are, like Harry Etchingham, “generally appreciative of the creatures in private”); second, the practice of “wheeling”—travel by bicycle—as a relatively novel mode of late Victorian transportation and technology.

In a comedic novel centered ultimately on social manners and potential marriages, the animals and transportation technology are at least as interesting as the expected explorations of manners and courtship: the curate’s approval of dogs that do not attack him, the search by would-be-suitor Harry for his beloved’s missing cat Trelawny, the unhappiness of the spaniel Tracy in the city and his move back to the country to rejoin his now indifferent companion Merlin, newly retired from rabbit and rat hunting.

The two repeating elements of animals and wheeling marry happily in the first third of the novel in a bicycle wreck occasioned by “a big loafing village dog.” Said wreck has the added bonus of producing a curse of the unfortunate animal (allegedly composed in Latin and translated into English), an account that will bring our selected excerpts—a mere skim of the 343 page novel—to a close.

|

| Frederick Pollock. Ella Fuller Maitland. The Etchingham Letters (New York: Dodd, Mead, & Company, 1899). |

Poor Tracy, he looks pathetically bewildered by the uproar of the [London] traffic and the perplexing avenues of bricks and mortar. |

We discovered our first “Etchingham Letter” describing the bicycle/dog mishap as a piece published serially in The Cloverhill Magazine, 1898, mistaking it momentarily for nonfiction. Ideal for our Gallery out-of-copyright series, we thought, but The Etchingham Letters, save for the book cover reproduced in the suite, is not illustrated.

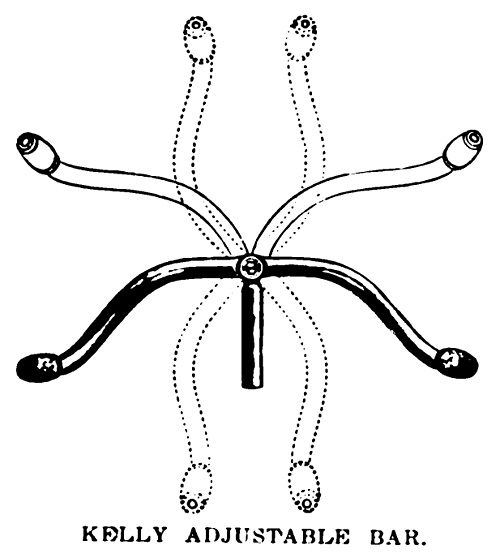

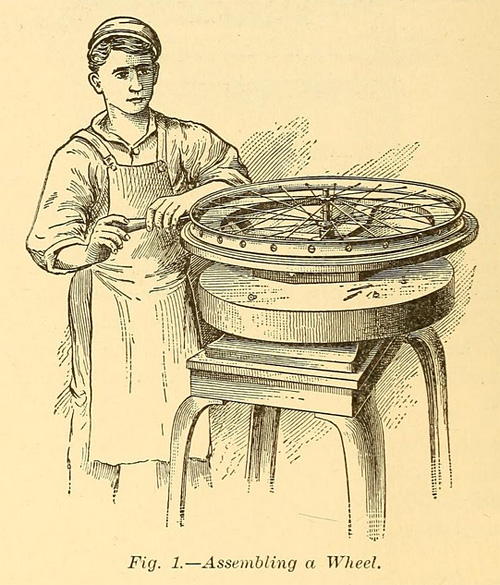

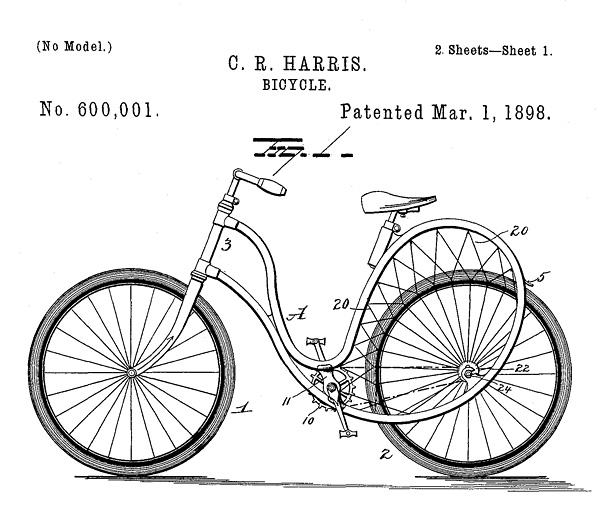

In something of a mashup, we have added to our excerpts images related to cycling from the 1880s and 90s.

Additionally, we include a mock advertisement imagined by Jem Etchingham in one of his letters to Sir Richard for “Roly-Poly Bicycles”; we have set the text of Jem’s joking advertisement as a visual element in Letter IV’s enclosure.

The letters are organized by number; we have retained those numbers in our excerpts, adding a title to each section quoted from the passage that follows it.

We have also taken full license with the paragraph breaks, opting for readability on Blackbird’s page. Though the first edition provides no dates, later editions of the book place the novel in time from “the second week in February to the second week in September, 1898.”

The guide to characters is our own, and since we have already given spoilers in our introduction, some small information about each character is given (without fear of repetition) so that the reader might better find her way.

|

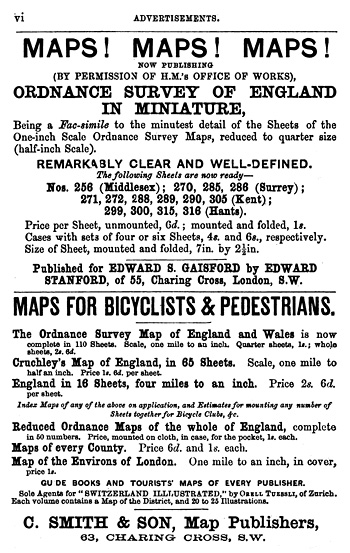

| Charles Spencer. The Bicycle Road Book: Compiled for the Use of Bicyclists and Pedestrians. Being a Complete Guide to the Roads of England, Scotland, and Wales. (London: Griffith and Farran, 1880). |

Wheeling, like mountaineering, has some unavoidable accidents besides the (n+1) avoidable ones. |

The Animals

Cats

Trelawny

(moved from Tolcarne to London under the care of Elizabeth and Cynthia,

and prone to disappearances)Luna

(the butter eater)

Dogs

Tracy

(a spaniel bewildered by London and eventually returned to Tolcarne)Merlin

(retired from hunting)Songstress

(a mute basset-hound)Blanch & Sweetheart

(the other dogs)“a big loafing village dog”

(the anonymous animal that causes the bicycle wreck)

The Two Principal Sibling Letter Writers & Brother Harry

Sir Richard Etchingham [Dickory]

(a widowed veteran returned from India to settle at the family home in Tolcarne)

Elizabeth Etchingham

(sister to Sir Richard and Harry; removed from Tolcarne to London with Lady Etchingham, Cynthia, and Harry)

Harry Etchingham

(brother to Sir Richard and Elizabeth)

Remaining Cast (London)

Laura, Lady Etchingham

(widowed, stepmother to Sir Richard, Elizabeth and Harry Etchingham)Cynthia Leagrave

(niece and ward of Lady Etchingham)Mr. Biggleswade

(vicar of Vivian Dampshire)

Blake

(in service to Lady Etchingham’s London household)Mrs. Vivian

(an in-law to the Etchingham family)

Remaining Cast (Tolcarne)

Margaret Etchingham

(Sir Richard’s daughter and the most accomplished cyclist at Tolcarne)Edward Follett

(the vicar of Much Buckland)Septimus Weekes

(the curate)William Shipley

(“learned medievalist from the Record Office”)

Enticknap

(gardener/groundskeeper at Tolcarne)

Remaining Cast (Silvertoe College, Oxbridge)

James [Jem] Etchingham

(Etchingham cousin and a Fellow at Silvertoe College, Oxbridge)Blunham and Howard

(Fellow tutors at Silvertoe)

|

excerpts of Letter I, “He Appreciates the Creatures in Private”

From Miss Elizabeth Etchingham, 83 Hans Place, London, S.W. to Sir Richard Etchingham, Bart., Tolcarne, Much Buckland, Wessex.

February, 1898.

Most excellent Richard,

. . . .

Harry very kindly met his stepmother, his sister, and a pyramid of luggage, which included a bicycle and a bath-chair, at Paddington. . . . Trelawny, Tracy, and the bullfinches were more en evidence than conventionality permits certainly, and perhaps the sight upon a platform of a flustered cat and dog and a cage of fluttering singing-birds proved too much for my brother—greatly as he appreciates the creatures in private—for he vanished from among us as instantaneously as if he were a conjuring trick, and, though I heard his foot upon the still uncarpeted stair at midnight, we saw him no more till the next morning. (“I was surprised, M’m . . . that Trelawny did not catch the Major’s eye at the station; set off so, as he was too, by his blue riband, and the cat looking for notice,” was Blake’s comment on the platform episode—the episode not of defective vision, but of cutting dead.)

. . . .

I am impatient for news of Tolcarne, and I must be told quickly what you think of everybody, and how things generally prosper. Is Margaret ordering the house as wisely as if the child were her own grandmother? and is she mothering the garden? The almonds and the mezereon must be now ablow, and soon there should be white violets everywhere.

You will, I fancy, come to like the Vicar and Mrs. Follett, and you will, I know, terrify poor Mr. Weekes, the very meekest of meek curates.

Let me hear, too, if the dear old dogs, “Tray, Blanch, and Sweetheart,” are taking kindly to the change of masters. I hope so. Mr. Weekes said to me once, in his painful conversationmanufactory efforts, “I like your dogs, Miss Etchingham; they don’t bite curates.”

Our Tracy walks abroad in Cynthia’s company—Tracy wearing a coat cut with a Medici collar. (Tell Margaret that Blake, when reproached for the inordinate length of time spent in the running up of a coat for his spaniel clogship, brought forward the plea, “I’m making Tracy’s coat, Miss Cynthia, with a Medici collar.)

Poor Tracy, he looks pathetically bewildered by the uproar of the traffic and the perplexing avenues of bricks and mortar. Cynthia and I must write and ask Mr. Follett whether spaniel history is repeating itself and if Herrick brought his “Spaniell Tracie” to his “beloved Westminster” from “dull Devonshire.” If so, the poet’s Tracie had little to trace, poor fellow, but his master, though London precincts were not as birdless as now.

As to Margaret’s friend Trelawny, we are congratulating ourselves that his cedar-wood-hued fur is a “good wearing” colour, and comes through a fog less discreditably than could the white coats of his still-inthe-country Persian relatives. Looking just now at his green eyes that shine like emeralds, it occurred to me that, besides flame, there is yet another thing—eyes—that London smoke cannot tarnish.

. . . .

Yours ever and alway,

Elizabeth

|

| The Modern Bicycle and Its Accessories: A Complete Reference Book.(New York: The Commercial Advertiser Association, 1898). |

. . . Our cousin Jem of Silvertoe is said to be a mighty man of wheels . . . |

![]()

excerpts of Letter II, “Animals First, Of Course”

From Sir Richard Etchingham to Miss Elizabeth Etchingham

February, 1898.

Mv Dear Elizabeth,

I congratulate you on having effected the concentration of your miscellaneous forces in town without having any casualty to report. As to good order, perhaps I had better say nothing. Your description of the scene on the platform is rather like the too famous retreat of Colonel Monson:

Ghore par haudah, háithi par zín

—in English, adapted to the circumstances,

“Dogs in cages, and dicky-birds in muzzles.”

However, there you are, and still the best of correspondents, though I no longer have to rely on you for home news. We used to dream of being together when India had no more use for me; instead of which we find ourselves comparing notes on settling down in different places.

. . . .

As to our people—animals first, of course.

Merlin the ancient, who was young and frisky when I last went out, is confirmed in his opinion that I am really the same person.

Songstress, apparently so called from being of a rather silent habit, and of even more melancholy looks than a basset-hound has any right to be, has taken a sort of quiet fancy to Margaret. Curates’ legs do not interest them, naturally. Why should they? Bishops’ legs, now—nice tight gaiters all over, buttons to take hold of—are quite different. Dear old Bishop Abraham was irresistible to the college beagles at Eton. It was against etiquette for him to notice their existence—and he didn’t.

Mr. Weekes must either be nervous about dogs, or generally anxious about his own person, or—as indeed you most plausibly conjecture—at a pass for something to say. He is but a kutcha sort of young padre. or it might be juster perhaps to say, in literal English, halfbaked, for he may make a man yet. Just now he is distracted between shyness and zeal to improve in cycling (it will be so useful to him for visiting his flock in a scattered parish).

Margaret is the only person here, for the moment, who knows much about it, and she conducts us on easy rides fit for beginners. She says she won’t answer for the consequences if either of us is turned loose on these roads before she certifies us quite safe. If I am a good old man, she holds out hopes that in a few weeks more I may ride all the way down the hill to Little Buckland. You know the curve and the steepness thereof—no, you don’t; looking down a hill from a bicycle is quite unlike looking down it in any other position.

At present, that caution-board is more formidable to me than any Ghazi’s green turban to any soldier. Our cousin Jem of Silvertoe is said to be a mighty man of wheels; I am writing to him for some general advice, as Mr. Weekes, having an inordinate respect for every kind of authority, and having heard of Jem in that capacity from some Oxbridge friend, would not rest till I did. That youth would rather be stuck on the devil’s pitchfork—being the real proper devil—than wafted to heaven on the wings of an unlicensed seraph. However, Jem ceases from his lectures in a week or two now, so there is no harm in asking him.

Weekes is, so far, less able on his machine than I am; but he has got up the slang elaborately, and indited a list of questions for Jem which I don’t more than half understand.

Margaret sends me packing to dress for dinner. What a treasure is a methodical daughter! . . . I came home to enjoy a spell of being governed.

Richard Etchingham

|

| from an advertisement for Surrey Machinist Company. Charles Spencer. The Bicycle Road Book: Compiled for the Use of Bicyclists and Pedestrians. Being a Complete Guide to the Roads of England, Scotland, and Wales. (London: Griffith and Farran, 1880). |

As to that bicycling business, well can I picture your wicked child entertaining herself with Mr. Weekes’s timidities. |

![]()

excerpts of Letter III, “Suspiciously Snuffing the Biggleswade Boots”

From Miss Elizabeth Etchingham, 83 Hans Place to Sir Richard Etchingham, Tolcarne.

March, 1898.

Dear, oh dear, oh dear,

The vegetables have never come. Elements and Enticknap permitting or not permitting, send, best of brothers, a mildewed beetroot or frost-bitten cabbage at once. Remember that our immortal feelings, not our mortal appetites, are at stake, and in such a case a very turnip’s top may prove ambrosia.

. . . .

We were invaded by Mr. Biggleswade (once Jem’s Oxbridge acquaintance, now the Vivian Dampshire vicar). Having pretty well ignored our stepmother, whose politeness to clergymen of every persuasion is unfailing, he produced from his pocket a very slim volume and presented it to Cynthia—“as I promised.”

“Are those your pagan love-poems, or the verses in which you generously patronize Christianity, Mr. Biggleswade?” inquired Mrs. Vivian. “It is so kind of Mr. Biggleswade to believe—most thoughtful and considerate, is it not?”

Thereupon Harry’s “gwuff” laugh was heard. . . . Mr. Biggleswade, however, lost none of his jaunty airiness of demeanour. He fixed his Oxbridge smile for a moment upon Mrs. Vivian, and admitted, as he seated himself on the sofa by Cynthia’s side, that he “did not pretend to be one of the old school of clerics.” What he then went on to say to Cynthia, “not knowing, can’t say,” to quote old nurse, but evident was it that his discourse embarrassed the child. . . .

Mr. Biggleswade’s bantering laugh grew more frequent. Will Harry go to the rescue, I wondered, or shall I?

But as I wondered, lo and behold, suddenly the Oxbridge smile petrified, Mr. Biggleswade’s cheek blanched, and terror wrote itself in his eyes. Had influenza marked him for its own? Had he just developed a conscience, or a heart disease? No. Dropping my gaze from his face to his feet, there saw I our Trelawny suspiciously snuffing the Biggleswade boots; and having sniffed and not approved what did our Trelawny but proceed to sharpen his claws upon the leg of Mr. Biggleswade’s chair, as if preparing weapons of attack.

Poor pseudo-pagan love-poet. Poor patron of Christianity. Poor disconcerter of shy Cynthia. With an incoherent reference to train-catching, the Thing was gone.

“Does your cat like cream, Elizabeth?” then asked honest Harry.

To murmur “Not enough to go round” was to waste breath.

Out ran the contents of the cream-jug into the saucer of Harry’s teacup, down to the very last drop. Lowlily bent Harry, and with a very fair imitation of the air of self-conscious condescension with which Mr. Biggleswade serves the Church, did Trelawny deign to lap the cream held conveniently by a major in Her Majesty’s army to the level of his Persian lips.

There, now you know all about it.

As to that bicycling business, well can I picture your wicked child entertaining herself with Mr. Weekes’s timidities; but should Jem unbend in his reply to the cycling questions, the poor “half-baked” man will, I trust, be supplied with an expurgated edition of Jem’s wit.

And now, Richard . . . pat the ancient Merlin and the mute Songstress for me, and beg Margaret, as cats do not always care for caresses to make Luna’s pat from me a—pat of butter. . . .

Yours to command,

Elizabeth

|

| S.D.V Burr. Bicycle Repairing: A Manual Compiled from Articles in The Iron Age. (New York: David Williams, 1896). |

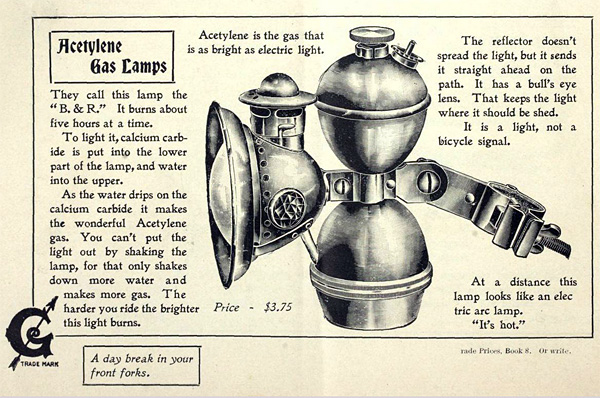

I don’t see how I could answer a string of questions from a man I have never seen which range over the whole art of cycling and every part and fitting of a machine from lamp to backstays. |

![]()

excerpts of Letter IV, “Out of Harm’s Way”

From Sir Richard Etchingham to Miss Elizabeth Etchingham

March, 1898.

My dear Elizabeth,

. . . .

Jem has written to me from S.T.C. [Silvertoe College], and it won’t do to show Mr. Weekes at all—in fact, I can think of nothing better than sending it on to you to be out of harm’s way.

. . . .

Your affectionate brother,

Richd. Etchingham.

Enclosure, “The Whole Art of Cycling”

From James Etchingham, Assistant Tutor of Silvertoe College, Oxbridge, to Sir Richard Etchingham, Tolcarne.

My Dear Sir Richard,

It is the end of term, true enough, but with that end comes a business called Collections, not conducive to leisure for tutors.

Anyhow I don’t see how I could answer a string of questions from a man I have never seen which range over the whole art of cycling and every part and fitting of a machine from lamp to backstays.

The short answer to about three quarters of them is that it is a matter of taste and he had better find out what suits him and stick to it. Otherwise the Rev. Septimus may take in a penny cycling paper and become a valued correspondent. He can get as many answers as he likes that way, and I should think it would just do for him.

If you wanted to know anything I could tell you for yourself, that would be quite different. But I guess I may be riding about your country in the vacation, and it will be simpler to call in person one day and see how you are getting on.

. . . .

Perhaps even Mr. Weekes need to be warned against the current advertisement of this type:—

|

Here comes a man with an essay on the Platonic Number. I know it will be about everything except the text.

Your most truly, rigidly, and rotarily.

James Etchingham

![]()

excerpts of Letter V, “People Who Cannot Be Left”

From Miss Elizabeth Etchingham, 83 Hans Place Sir Richard Etchingham, Bart., Tolcarne

April, 1898.

Dear, dearest Richard,

Thank you very much for the vegetables; but, oh, the irony of life. The vegetables waited to come till a time when my spirit refused to feed upon Wessex beetroot or to find solace and refreshment in a Tolcarne Brussels-sprout.

. . . .

How much these days that have something of spring about them make me wish to shake the dust of London off my feet and take tickets to Much Buckland for poor, country-loving Tracy and myself. I long to see the blowing of the daffodils, the Wessex “Lent-roses,” in Little Buckland meadow, and the flitting to and fro of the long-tailed tits, to whom the alders by the river serve as withdrawing–rooms. (Birds are conservative, I think, in their vocabulary.)

The first breath of spring, when it reaches one in town, is depressing. It is at least to me, and gives me, with its suggestion of the unattainable, a doleful, Amiel-melancholy. But stay here I must, for Laura cannot be left. If you ever see in your sister any sign of this inconvenient instability, please crush it out at once.

People who cannot be left, and who, therefore, must be provided with constant companionship, levy a rather hard tax upon their relations. But Laura is made so, and I do not feel it my duty to discipline her out of her faults, as would some one cast in the special constable mould. It is impossible to persuade her to leave home herself during the rheumatism régime. She is starved in her friends’ houses for want of proper food, poisoned by the strength of their tea, roasted by their fires or blown out of window by their draughts. (Other people’s draughts are draughts; our own are ventilation all the world over, you may have noticed.) So here I am and here I must remain.

. . . .

Your loving Sister,

Elizabeth

|

| C.R. Harris. Bicycle. United States Patent 600,001, 1898. |

If you have any interest left for my small affairs, know that I had actually ridden, with exceeding caution, down the Little Buckland hill. |

![]()

excerpts of Letter VI, “Only Pleased and Amused”

From Sir Richard Etchingham to Miss Elizabeth Etchingham

April, 1898.

My Dear Elizabeth.

. . . .

Mrs. Tallis, who lives by herself at Little Buckland . . . caught sight of Margaret on her bicycle, who had been round on errands, and came back to convoy me. We had meant Mrs. Tallis not to see it the first time; in fact, Margaret was quite sure it would be shocking to her. But she was only pleased and amused, and we rode off with a blessing waved after us from the porch.

If you have any interest left for my small affairs, know that I had actually ridden, with exceeding caution, down the Little Buckland hill. Margaret says I begin to do her credit.

Jem may be here any day now, and will perhaps condescend to put some touches to our education.

There is a shade of something amiss about Margaret these last days; she looks worried at times, and I don’t think it is the housekeeping or anxiety for her or my improvement in cycling. No doubt she will tell me in good time if it is really anything.

The Folletts are expecting one Shipley, a very learned medievalist from the Record Office, to spend a few days at the Vicarage, and examine some documents in the neighbourhood, or in the Thursborough archives. I am not sure which. They have hardly met Mr. Shipley, though Mr. Follett knows his work well. Margaret and I are to help to entertain him. We are all rather in fear of the learned man, and try to comfort one another with the hope that he may not turn out altogether too weighty, or otherwise very formidable.

Your affectionate Brother,

Richard Etchingham

|

| Three Good Tires—Also Sundries, (Toronto: The American Tire Company, Limited, 1899). |

As Mr. Weekes is barely capable of riding and talking at the same time, his discourse was adorned by narrowly averted collisions with the Squares’ family coach, a farmer’s cart, a donkey, a wheelbarrow, and Margaret herself. |

![]()

excerpts of Letter VII, “The Etiquette Difficulty”

From Miss Elizabeth Etchingham, 83 Hans Place to Sir Richard Etchingham, Tolcarne.

April 1898.

Dear Dickory,

. . . .

Do not dock me when you write of the Tolcarne news, of the Tolcarne sayings and doings. They throw up the window and freshen the air of the room (ventilation, not draught).

Is Enticknap, as usual, grudging growing-room to everything but a cabbage, and hungering—I trust futilely—to dig the borders? Don’t let him. If he had his way he would destroy every vestige of blossoming vegetation. The good creature confuses a Sahara and a flower-garden, and all that he does not cut down he holds it his privilege to dig up.

I wonder if Merlin, poor old dog, still, every fine morning, takes a sun-bath on the terrace? I liked to see him throw himself down before the big myrtle with a sigh of reposeful content. And tell me if the cocks and hens flourish, and if you now are called upon to find names for the infants of the poultry yard.

Great was Enticknap’s embarrassment when Margaret gave her own name and Cynthia’s to two of the chickens. With “Miss Cynthie the cock” and “Miss Margrot the pullet,” he finally solved the etiquette difficulty.

My salutations empressées to you and to everything at Tolcarne, and those of Trelawny to the birds—robin, linnet, thrush. Much does he wish, horrid fellow, that it were for him to devastate the nests this spring. Much do I rejoice that it is not.

Good-bye, good-bye.

Elizabeth

![]()

excerpts of Letter VIII, “Don’t Upset My Machine”

From Sir Richard Etchhingham to Miss Elizabeth Etchingham

April 1898.

My dear Elizabeth,

. . . .

Mr. Weekes, the curate, who began his relations to me with a rather exaggerated version of the civility due from a younger man to a considerably older one, has become more and more obsequious the last week or two, till at last it was positively oppressive. Margaret, regarding him as an inoffensive person to whom it would be a sin to refuse charity, continued to instruct him in cycling along with me.

Last Thursday morning he came round when I happened to be well occupied with letters . . . and I said that if Mr. Weekes and Margaret would start on our usual run—the one approximately flat piece of the Thursborough road near us which you once complained of as our one dull walk—I would come after them presently and overtake or meet them.

“Huzur,” said Margaret (she will call me Huzur, though I have explained to her that it is quite pointless), “can’t you really come with us?” But I really could not very well, and saw no need for it.

In about half an hour I stepped out to fetch my hired machine from the portion of the stable which Margaret has converted into a cycle-house, when Margaret came riding in at the gate, faster than usual, and almost ran against me, with Mr. Weekes panting and wobbling after her. They dismounted and took their bicycles in.

(Mr. Weekes’s lives here till he can find storage elsewhere—there is no place at all in his lodging in the village, and as his and mine were hired from the same shop in Thursborough at the same time, it seemed the natural thing), and as I was moving in the same direction there came out in Margaret’s most practical housekeeper’s voice—the one she uses when something stupid aggravates her—

“Do stop talking nonsense, Mr. Weekes, and don’t upset my machine.”

Then a limp black figure, dusty as to the knees, came scrambling past me with a hasty salute most unlike Mr. Weekes’s usual ceremony; and when he was well out of the gate, Margaret emerged and half drew, half drove me into the study.

“What,” said I; “you don’t mean to tell me he has—?”

She looked as if she did not quite know whether to laugh or to cry—you know I become imbecile when people cry—but happily the laugh turned the scale, and, after giving a little choke or two, she collapsed on a stool in a violent fit of laughter.

“Yes, indeed,” she said, when she could find words, “and he’s been proposing all the time.”

Apparently Mr. Weekes accepted the chance as a providential omen, and as soon as they were fairly started he began to blurt out incoherent compliments, in which the virtues of Margaret, Much Buckland, and myself were hopelessly tangled, and then reeled off what he intended to be a proposal in due form, with a full exposition of the secular and spiritual advantages that would accrue to both parties, and to the people of the Bucklands, from Margaret becoming Mrs. Septimus Weekes.

As he is barely capable of riding and talking at the same time, his discourse was adorned by narrowly averted collisions with the Squares’ family coach, a farmer’s cart, a donkey, a wheelbarrow, and Margaret herself. All these events gave Margaret plenty to do in looking out for herself and ejaculating imperative cautions, so she could only get out a few words of dissent. When he followed her into the stable he essayed to go down on one knee, but, the space being limited, he only achieved stumbling over Margaret’s machine and barking his shin against the mud-guard.

Net result—Mr. Weekes must find quarters for his bicycle somewhere else without loss of time.

. . . .

Margaret . . . had been suspecting the catastrophe for some days, but looked, as I should have looked, for something much more formal and dignified. She is not exactly angry with the man, but vexed at his folly. Such persons do seem a blot on the reasonableness of things.

Your loving Brother,

Richard Etchingham

![]()

|

| W. Gordon Stables Health Upon Wheels, or, Cycling: A Means of Maintaining the Health and Conducing to Longevity. (London: Iliffe and Son, 1889). His other volumes include Medical Life in the Navy, Turkish and Other Baths, and Tea: The Drink of Pleasure and of Health.” |

Enticknap said to me once, with a note of interrogation in his voice, that he had “heard say” the whooping cough was never taken by a child who had ridden upon a bear. |

![]()

excerpts of Letter IX, “Trelawny, Worshipped by Cynthia, Has Wandered Far”

From Miss Elizabeth Etchingham, 83 Hans Place to Sir Richard Etchingham, Tolcarne.

April 1898.

Dear, dearest creature,

Poor Margaret—poorer Mr. Weekes. But what a goose the poorer man must be to have supposed himself capable of converting Margaret into Mrs. Septimus Weekes. There is a certain ingenuosness about him that I always rather liked, and a meekness not in keeping with the hardihood of his last move.

Do you know, I wonder, the tale of his first appearance in the Tolcarne pulpit one Sunday afternoon, as told by Blake?—“Mr. Weekes, M’m, up he went, and he looked round and round all in a flutter, and then says he, ‘My thoughts have gone from me. Will you excuse me?’ and down he ran, scared as a hen by a hawk.” I don’t feel sure that valour was absent from this explanation, though terror certainly takes people differently—making some speak when conscious that thought has left them.

. . . .

Later. —A letter “to hand” from Harry. He seems happy. The river—oh, unique river—is in good condition, and he has killed and is sending south a fish. He begs to inform me that his “waders, when hung upon a hedge to dry, were the subject of much perplexed discussion by some French tourists t’other day. Mystery finally solved to the satisfaction of all parties. Waders were undoubtedly worn ‘for the ascent of Ben Nevis.’”

So effectually mended is Harry’s heart—if by Ada Llanelly ever broken—that I should not be surprised if—can you guess? No? Well, answer me this: Is it all in the day’s work that our good brother should spend hours in the attic box-room sweeping the leads and roofs through a field-glass, when Trelawny. worshipped by Cynthia, has wandered far?

I, too, worship Trelawny; but would Harry throw over anybody, everybody, anything, everything, rather than Trelawny should vanish into space, were his sister’s heart alone lacerated by the thought of Trelawny’s disappearance? And why, please, did he nearly put out his sister’s eye with the rib of her best umbrella, snatching the umbrella from her without so much as a “by your leave” lest Cynthia’s feathers should suffer. Are not my eyes of more value than many feathers, except in the opinion of one under the spell of the wearer of the feathers?

. . . .

Cynthia is an attractive thing. Pretty as a Cosway miniature, and pretty to live with: which beauty is not always. And she seems an affectionate loveable little soul; not possessed, perhaps, of Margaret’s strength, but the strength may be there, dormant, for all I know. And then she has that invaluable old-fashioned possession—a conscience. The Fates would be kind to Harry if they did give him Cynthia as his wife, nor would they, in my humble opinion, do Cynthia the while an ill turn, for men, as kind, as upright, as crystally honest as Harry are not plentiful as blackberries on hedges.

. . . .

Thank Margaret for her nosegays. The great boughs of pear-blossom and the forget-me-nots have dressed us out elegantly in white and blue; and the violets, if the Jinnestan romance tells truly, should ward off the cruel and evil spirits “whose malignant nature is intolerant of perfume.”

How is the flower-perfumed world at Tolcarne? Today, Good Friday, potato planting, according to Devon tradition and superstition, is the rule in every cottage garden; and in yours too, probably, for Enticknap is a stickler for old custom and luck-lore. Bid him transplant some parsley, and see if your will or his superstition prevails. He said to me once, with a note of interrogation in his voice, that he had “heard say” the whooping cough was never taken by a child who had ridden upon a bear. In reference to this, Mr. Follett, I remember, told me that when bear-baiting was in fashion, the bear-owner’s profits were largely augmented by money received from parents whose children, for their health’s good, had ridden the bear.

Now good-bye. Take care of yourself, and don’t forget to outlive me. . . .

Your loving sister,

Elizabeth

|

| Frances E. Willard. A Wheel within A Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, With Some Reflections Along the Way. (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1895). |

Riding down from Mill Hill to Hendon, Jem says, is like being tossed in a blanket among sacks full of stones; and the steep places are really almost dangerous, by reason of their roughness, to any one but an experienced rider. . . . |

![]()

excerpts of Letter X, “Experiment Under Secret Instructions”

From Sir Richard Etchingham to Miss Elizabeth Etchingham

April (Easter week), 1898.

My dear Elizabeth,

Harry’s attentions to Trelawny, which you report with so much interest, afford a curious example of what the modern naturalist calls “throwing back.” Pursuit of strayed animals was amongst the earliest functions of Intelligence Departments. In fact, there is a stage of society, still possible to observe in parts of India, where the chief occupation is lifting your neighbours’ cattle, diversified by expeditions for tracking, and if possible recovering, the cattle which he has lifted from you.

. . . .

Now the sport of tracking stolen oxen is not easily practiced in modern England, least of all in cities; but by the legitimate substitution of the cat, a smaller and swifter animal, and following the trail across housetops, where the signs of passage are less obvious than on a road, the material conditions are reconciled with modern civilization, and the discipline of intelligence with the concomitant satisfaction of the sporting instinct, is not only preserved, but improved.

There is a piece of evolutionary argument for you. I have heard young civilians just come out with their heads full of Herbert Spencer deliver themselves of less plausible ones in all seriousness—and seen them do right good men’s work a few years later, when they had found out that the gods of Asia don’t rule their world according to Western books.

But a quite different alternative hypothesis occurs to me about Harry’s conduct: perhaps our War Office wants to go one better than the Germans, and train cats to act as orderlies. In any case, it is evident that he is carrying out some kind of experiment under secret instructions; so be careful how you talk of it.

As for the sunshade and feathers incident, I give it up, having never had anything like it in my official experience.

. . . .

We had a pleasant little dinner-party at the Vicarage last week. . . . I told Mr. Shipley how the Vicar and I began to fraternize over the curse of Ernulphus.

. . . .

“I have had to look at Anglo-Saxon charters, though not often,” answered Mr. Follett, “and I have noticed those clauses, which I suppose you refer to, denouncing various penalties in the world to come upon any one who may attempt to interfere with the pious king’s gift; but they seem to me fragmentary and fantastic work.”

“Only you should consider the variety,” said Mr. Shipley. You may have your portion with the traitor Judus,

which is perhaps the commonest form;

you may be swallowed up by Dathan and Abiram;

your soul may be hooked out of your body with devils’ claws to be boiled in Satan’s cauldron world without end;

you may be devoured by the Salamander; you may be smitten sunder with the falchion of Erebus; or, contrariwise, you may be delivered over to the malice of the Pennine demons, that they may plague you with the iciest blast of the Alps.”

. . . .

Talking of the garden, I cannot get any good word for the bullfinches from Enticknap. He sticks to it that they are a downright mischievous lot, and he has seen a “proper rendyvoo” of them eating the buds “zo vast as they could.”

. . . .

Your loving brother,

Richard Etchingham

|

| Three Good Tires—Also Sundries, (Toronto: The American Tire Company, Limited, 1899). |

I always thought that his frolic humour would land him under a wheel. Now, I suppose, he is racing round and round the lawn, fringes and love-locks flowing in the wind. |

![]()

excerpts of Letter XI, “The Dog Seems Preoccupied”

From Miss Elizabeth Etchingham, 83 Hans Place to Sir Richard Etchingham, Tolcarne.

April, 1898.

Mv Dear Dickory,

Thank you very much for the vegetables that have just come, and thank you very much for your letter containing the curses, etc. Cauliflowers and curses thankfully received, dear. And as you are all so learned in such matters, tell me now the words of Hecate’s ban, “With Hecate’s ban thrice blasted, thrice infected,” or perhaps Merlin or Songstress, though not ban-dogs, would gratify my curiosity. When I begged Tracy to do so he said the thing had slipped his memory. The dog seems preoccupied. He detests the town.

. . . .

Harry, the hunter, instigated by primal instinct, sweeping the chimney-pots through a field-glass for Trelawny, the prey, is a picture pleasant and profitable to contemplate. That the job pertains to the work of the Intelligence Department is an equally pleasing suggestion, and as Imperial interests may be bound up in the business, I will take your advice and not divulge the fact to any but an Anglo-Saxon when Harry and field-glass are again so engaged.

Cats are full of contrivance and resource, and with Trelawny as his orderly—or perhaps rather as his colleague, for the race is intolerant of authority—my brother might go further and fare wars. Talking of throwing back and kindred subjects, is Harry the hue of the primal man? According to the author of a book I lately read, Trelawny’s cedar-coloured coat is not far removed from the colour of the primal cat—sandy.

. . . .

Elizabeth

![]()

excerpts of Letter XIII, “His Little Empty Collar”

From Miss Elizabeth Etchingham, 83 Hans Place to Sir Richard Etchingham, Tolcarne.

May, 1898.

“Trusty and wel beloved, we greet you well.”

“Trusty and wel beloved” you are missed. There was more luck about the house when you were here.

Tracy too is missed; and his little empty collar, with its inscription, 83 Hans Place, has now something of the sacred relique about it in Cynthia’s eyes.

But it was cruel to keep him in London. Spaniels are not the dogs for a town, and I always thought that his frolic humour would land him under a wheel. Now, I suppose, he is racing round and round the lawn, fringes and love-locks flowing in the wind. Does he still pause in his impetuous career to insult Eld in the person of blind old Merlin with belated invitations to play?

. . . .

It was to-day, was it not? that Mr. Follett was to guide your steps to Bratton Leys, there to see the “devil’s door” in the north wall of the church? I suppose the door is no longer thrown open during the Baptismal service, for the devil to escape at the Renunciation, and carefully bolted and barred on all other occasions?

Mr. Shipley visited us yesterday evening. He seemed very sorry to have come just too late to encounter You. I told him that I had hear that when Medievalists met, the devil, who ruled their period, had, naturally enough, taken a prominent part in the conversation, and he answered that the conversation was of angels too.

. . . .

The question of the existence of ancient vineyards in Britain is, I see, discussed in one of the newspapers. There were vineyards at Ely, at all events, a very long while ago, according to the Latin rhyme, which was Englished long ago too. I was too lazy to send the rhyme to the newspaper—but here is the 17th Century English version for you:—

Four things of Elie Towne much spoken are

The Leaden Lanthorne, Maries Chappel rare

The mighty Mil-hill in the Minster field

And fruitful ineyards in which sweet Wines do yield.

Good-bye for now Dickory, and write again soon.

Elizabeth

|

| Charles Spencer. The Bicycle Road Book: Compiled for the Use of Bicyclists and Pedestrians. Being a Complete Guide to the Roads of England, Scotland, and Wales.(London: Griffith and Farran, 1880). |

. . . Riding down from Mill Hill to Hendon, Jem says, is like being tossed in a blanket among sacks full of stones. |

![]()

excerpts of Letter XIV, “Reduced to Terms of Canine Philosophy”

From Sir Richard Etchingham to Miss Elizabeth Etchingham

May, 1898.

My dear Elizabeth,

. . . .

Mr. Weekes has negotiated an exchange of duty, to the relief of all parties. I don’t much think we shall see him here again.

Tracy is very well and happy, though we cannot get Merlin to treat him with anything better than dignified acquiescence. Merlin has arrived at the stage of the very holy Brahman who, having fulfilled all his duties as a householder, left a son to maintain the family sacrifices, and master of all the wisdom of the Upanishads, retires from the world and spends the rest of his life in pure meditation: which, being reduced to terms of canine philosophy, signifies that Merlin has ceased to hunt rabbits, and is almost indifferent to the mention of rats.

. . . .

Jem has been investigating the roads north of London (I think he had some examination or conference at Mill Hill), and sends me a savage growl at the Middlesex County Council for the state in which they leave their roads in those parts. Riding down from Mill Hill to Hendon, he says, is like being tossed in a blanket among sacks full of stones; and the steep places are really almost dangerous, by reason of their roughness, to any one but an experienced rider—not merely “dangerous” in the danger-board sense, which, in the home counties at any rate, means, with very few exceptions, that you can ride down with care in ordinary conditions of weather and surface.

. . . .

I wonder whether Tennyson’s “Promise of May” contains a cryptic allusion to May weather. It is strange that the name of that poetic month is conspicuous in the two least good pieces of work he ever did (the other being the May Queen). Mr. Follett remembers Tennyson once saying, a long time ago, that an English summer was like living in an undressed salad. All the neighbors are grumbling at the unseasonable weather. I think of what the sun is now in the desert round Bikanir, and feel like Anson’s sailors when they hailed the “chearful gray sky” on the Peruvian coast after a long baking in the south seas.

Your loving brother,

Dickory

|

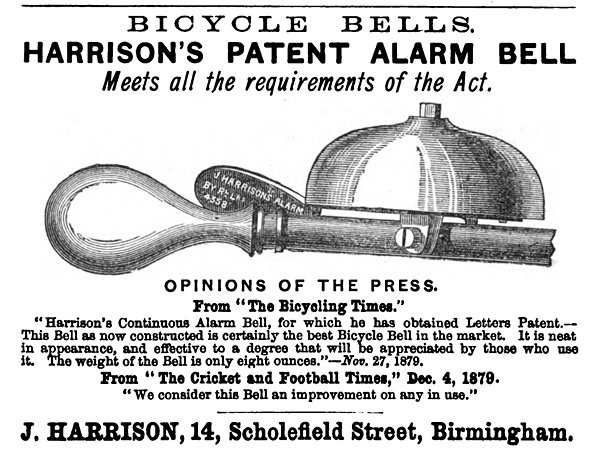

| “Harrison’s Patent Alarm Bell” Charles Spencer. The Bicycle Road Book: Compiled for the Use of Bicyclists and Pedestrians. Being a Complete Guide to the Roads of England, Scotland, and Wales.(London: Griffith and Farran, 1880). |

Maledictus sit etiam per omnia rotabilia quae fecit Dominus. . . |

![]()

excerpts from XXIV, “Incipit Excommunicatio Canina”

From James Etchhingham, Silvertoe College, Oxbridge, to Sir Richard Etchingham

June, 1898.

My Dear Sir Richard,

. . . .

Blunham and I have been cursing the common dog for the last fortnight. Hunter, one of our promising scholars (a history man, so I don’t see much of his work myself), was out cycling with Blunham, and as they were coming home a big loafing village dog turned right across Hunter’s wheel and brought him down with a broken collar-bone. Wheeling, like mountaineering, has some unavoidable accidents besides the (n+1) avoidable ones.

Lucky it was not Blunham, who is in for the Schools this term, both for himself and for the College; and it was one of the first remarks Hunter made, which does him credit. He is a cheerful man, and has been finding amusement in learning to do as much as he can with his left hand. I suggested a trial of Leonardo da Vinci’s trick-writing, reversed from right to left, to be read in a mirror; and he finds it really comes easier to the left hand that way.

Blunham and I revisited that village within a few days and found the dog as fat and well-liking as could be. He was too large to be run over, and seemed not to have minded at all. So we could only relieve our feelings and Hunter’s with a curse. I got it a little touched up by Shipley one day when we met in town; of course he would have done it better. Still, it may amuse you and Mr. Follett.

Incipit excommunicatio canina.

Maledictus sit canis ille impudentissimus qui scholarem nostrum de rota eversit.

Maledictus sit cum omnibus malis canibus qui a principio mundi maledicti sunt.

Maledictus sit cum canibus Samaritanis qui carnes reginae Iezabel comederunt.

Maledictus sit cum latratore Anubi et ceteris daemonibus cynocephalis quot unquam in Aegypto atraverunt.

Procul sint ab ipso omnes benedictiones quas boni canes meriti sunt in caelo vel terra.

Minime videat annos Argi, neque cum angelis ambulet sicut canis Tobiae.

Maledictus sit per canes caelestes Sirium et Procyonem et Canes Venaticos.

Maledictus sit in triplici maledictione per Cerberum canerit infernum et per tria capita eius.

Maledictus sit coram domina regina et coram comitatu per omnes constitutiones de capistris imponendis.

Maledictus sit etiam per omnia rotabilia quae fecit Dominus, per primum mobile firmamenti et per gyrationes eius, per stellas, per planetas, et per polum, per solem, per lunam, per terram, et per omnium angelorum potentiam qui revolutiones ipsorum regunt.

Maledictus sit in ventorum oirculis et in ooeani gurgitibus.

Maledictus sit per rotam motricem universi quae est materia et per rotam directricem quae est spiritus et per catenam quae est ipsorum harmonia praestabilita.

Maledictus sit per rotas animalium alatorum quae vidit Ezechiel propheta et per eorum volubilit.atem in saecula.

Opprimat emn Fortunae improbae rota et semper in infimam sortem deiciat.

Torqueatur super rotam Ixionis et frangatur aicut rotae curruum Pharaonis.

Maledictus sit in orbe rotundo ac perfecto maledictionum.

Fiat, fiat.

Explicit.

~

Here beginneth the excommunication of the Dog.

Cursed be this dog of infinite wickedness who upset our scholar from his wheel.

Cursed be he with all evil dogs which have been cursed from the beginning of the world.

Cursed be he with the dogs of Samaria which ate the body of queen Jezebel.

Cursed be he with the barking god Anubis and all other dog-headed devils that ever barked in Egypt.

May all the blessings earned by good dogs in heaven or earth be far from him.

Let him in no wise see the age of Argus, nor walk with angels like Tobit’s dog.

Cursed be be by the heavenly dogs Sirius and Procyon and by the Hunting Dogs.

Cursed be he with a threefold curse by the hell-hound Cerberus and his three heads.

Cursed be he before our Lady the Queen and before the County Council by all and every the muzzling orders.

Cursed be he likewise by all wheeling things which the Lord hath made, by the prime mover of the firmament and his rotation, by the stars, the planets, the pole, the sun, the moon, and the earth, and by the power of all the angels who govern their revolutions.

Cursed be he in cyclones and cursed in whirlpools.

Cursed be he by the driving wheel of the universe, which is matter, and by the steering wheel, which is spirit, and by the chain, which is the pre-established harmony thereof.

Cursed be he for ever by the wheels of the winged living creatures which Ezekiel the prophet saw and by the swiftness of their rolling.

Let the wheel of Fortune in her wrath crush him and ever cast him down to the meanest fate.

Let him be whirled upon Ixion’s wheel and broken even as the wheels of Pharaoh’s chariots.

Cursed be he in a whole and perfect round of cursing.

So be it.

A true version.

~

Otherwise the chief news of this ever-being-reformed university is that we have been without a burning question for two whole terms.

Yours ever,

James Etchingham ![]()

Editor's Postscript:

Merlin, a potato tied round his neck with a string by Enticknap to draw off rheumatism, finally succumbs to old age and is buried “on the lawn under the filbert trees.” Songstress, in narrative counterpoint, has puppies. Tracy endures, “sulky at the exuberant youth” of the pups and despising cats though he will not “commit himself to anything so vulgar as active hostility.”

Trelawny, after “sauntering in with an air of unconcern,” eventually returns with Elizabeth to the country home at Tolcarne.

In letter XLVII near the close of the novel, August, 1898, Elizabeth writes to Sir Richard,

Dogs I consider the most loveable, cats the most fascinating, of animals. To fall beneath the

fascination of a cat, especially of a Persian cat, endowed both with the languour and fire of the

East, is to be under a spell. Friendship with a dog means the finding of a dear, perfect, sympathetic,

faithful friend. I don't know whether a cat’s fidelity is to be trusted.

When Azore ailed slightly the other day (he had taken to himself a ham from the sideboard), I sent for his

doctor, who gave me various instances of the gratitude of dogs as patients. I then inquired about

horses as patients. “Horses have no way to demonstrate,” he said. “And cats,” I asked. The

expression of Azore’s medical attendant changed from mild philanthropy to long pent-up indignation.

“Cat!” he exlaimed with heat—“I don’t get any gratitude from cats.” But this perhaps is an

expectional experience.

Acknowledgments and Biographical Notes