print preview

print previewback ROSS LOSAPIO

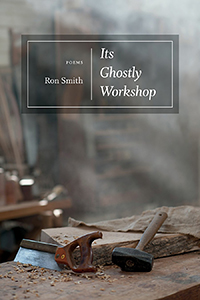

Review | Its Ghostly Workshop, by Ron Smith

Louisiana State University Press, 2013

|

During any journey—a vacation’s jaunt or lifetime’s grand trek—a time comes when the traveler must seek direction. Consider Odysseus, who, in Book XI of the Odyssey, conjures the spirits of those who have crossed over to the underworld: “I myself drew my sharp sword from along my thigh, / And poured a libation about it for all the dead . . . / I besought the feeble heads of the dead for many things.” The Ithacan calls lifeless Tiresias forward, among others, seeking counsel for his trip homeward. Ron Smith opens a similar portal in his third collection of poetry, Its Ghostly Workshop. While traversing its pages, the reader encounters T.S. Eliot, the New York Yankees of the ’60s, the speaker’s college football coach, and a host of others. Smith’s text charts an odyssey of its own, making port in Rome past and present, and then in the American South, that “gasping Confederacy” where the poet finds home.

Smith establishes the collection’s relationship between the corporeal and the mythic in its opening poem “Edward Teller’s Leg,” in which the father of the hydrogen bomb sails off the coast of Greece:

Sputnik, he said, as if he had launched it

himself. And our breathing fell away down

the mountain. We leaned back,

the tinkling sky

chandeliered with neurons. All the night before,

we had nosed past Piraeus, then through the cyclopean

slice of the Corinth Canal.

The poem strikes a tenuous balance between the subatomic and the gigantic, generating the text’s momentum, “though just enough to maintain / our arc over the earth, falling and not falling, / falling and not falling at all.” In many ways, this passage describes the modus operandi of Its Ghostly Workshop; it orbits without decaying, propels without disappearing into space.

As Tiresias swims up to Odysseus through spilled wine and blood, Edgar Allan Poe emerges in a triptych among Smith’s opening poems. “Mr. Poe Calls on Mrs. Shelton” displays the author in life, but, even so, Poe seems to detect the machinations of his summoning: “He’s firm. Yet feels / so temporary.” Poe awaits Mrs. Shelton in the following piece “Edgar Poe Tries to Get His Act Together,” and the veil slips further as the speaker wonders, “Why / would his hands and feet be cold / in the heart of a Richmond summer?” “Poe’s Last Words” winds up the spell as its tone and diction depart skillfully from its predecessors, and its meter and internal rhyme develop an incantatory rhythm. Eliot’s spirit arrives soon after, though his presence seems more devious:

If you’d just killed more birds or deer

in your youth, or had been the one

to behead that Jap Colonel, you think,

maybe he wouldn’t be there in the street

under his stupid bowler, about, it seems,

to tap your window with a furled umbrella . . .

As he pushes onward, the speaker’s literary predecessors become lurking wraiths. The poem’s somewhat indeterminate second-person perspective implies biting self-reflection and the act of writing becomes torturous ordeal and compulsion.

The middle third of Its Ghostly Workshop anchors itself firmly in Rome and, inevitably, raises the ungainly specter of “travel poetry.” However, rather than bounce from attraction to attraction, casting a tourist’s superficial eye on the Coliseum or the Spanish Steps, Smith’s poems immerse themselves in the culture—the art and food and ruins—posing difficult and occasionally critical questions. For example, the section’s opening poem, “At First,” begins, “O, I alone, detested Rome,” and continues in that vein to the complex conclusion:

glaring at the natives

I would later shrink in a tiny pad.

They passed temples older than Jesus

without turning their handsome heads,

columns in a cluttered hole

that chewed me with wonder and dread.

The speaker embraces culture shock and unease, causing the reader to wonder to whom history belongs if it goes unappreciated. From this launching point, the poems reunite more amicably with their atmosphere. In “Rome,” a missing watch functions as the catalyst for this transformation:

You look down at your reliable wrist

and there’s nothing, fog bank, niente,

nada, zip. Where your pulse beats,

there it is: The Void.

It’s time to look wildly around. Beetling

Berninis! Mammoth marbles! You’re

squeezed by grotesquely sweet angels!

Have you drifted

into Sant’Andrea della Fratte, where

the kitsch shall be with you always?

Doubt not, Pilgrim, but poke your finger

through the stone . . .

The action races along at a frantic pace. Diction and language become increasingly sensory and surreal until the poem’s subject surrenders any semblance of control: “It’s / still blank o’clock and nothing / will ever happen again.” Later, when approaching the city’s art (an obligation for any poet writing about Rome in such depth), Smith takes a refreshingly contrary approach, used most humorously in “Galleria Borghese, August”:

Today, the place is full of Ledas

getting laid. Leda con il Cigno, ancient,

on loan from the Capitoline, apathetically

endures her languid swan. My mother

used to say, Some people can make anything

boring.

In much ekphrastic poetry, the writer attempts to inhabit the work of art and imbue it with a life, which, too often, rings of artifice. Smith displays remarkable forethought and flexibility by surveying a museum in its entirety, its starch as well as its ecstasy.

The collection transitions quickly but deftly from ruminations on the foreign and mythic to firsthand experience and action. “Gods not men, those men, they ripped the sky roaring / in my sixth-grade Georgia dreams, floating / the base paths in the multitude’s hazy love.” Smith indulges in Homeric description to praise Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris in the poem “Yankees,” then explores mortal athletic prowess in more pragmatic language, as in “Splitting the Doubleteam,” when a football coach demonstrates proper technique:

one of us took a nickel-sized chunk

out of his scalp just above the hairline,

but he split us, fair and square. How you do it.

He got up, bloody now in five places,

and we all went on smashing one another,

only harder now, and a little sick

to our stomachs.

A self-proclaimed “stud,” the speaker seeks to pass through the crucible of competition and emerge godlike, though he must ultimately acknowledge his limitations. As the penultimate section of Its Ghostly Workshop progresses, the reader experiences equal parts admiration and disillusionment as the high school baseball star falls from grace (“The Day Jerry Suna Came to Baseball Practice Drunk”), college sports conflict with a passion for philosophy and British literature (“Double”), and the speaker delivers the bone-crushing block that sends an opposing kicker, limp and unresponsive, out of the game (“Perfect Hit”).

This remarkable journey from Poe to Rome to football field would fracture into disparity in less adroit hands, but Ron Smith melds these themes into a cohesive whole as Its Ghostly Workshop draws to a close. “Distraction,” for instance, opens with the lines, “Stop thinking / about Achilles a minute,” simultaneously invoking the Greek warrior and the tendon so crucial to athletes, and continues:

or you’re going to miss

this wonderful light

all around you. Those

royal rednecks didn’t

give two damns about

yarrow or coreopsis or

a shaft of pure vision

like that one falling

on St. Francis . . .

Smith expertly commands the elements that comprise his latest collection, ultimately arriving at the text’s title poem, in which the speaker imparts wisdom to his grandson as, one might imagine, Odysseus does for Telemachus upon his long-awaited homecoming: “Don’t wield too long nor grip too hard / what you take for truth. Be always prepared / to let it go. Let it go.” ![]()

![]()

Ron Smith is the author of Its Ghostly Workshop (Louisiana State University Press, 2013), Moon Road: Poems, 1986–2005 (Louisiana State University Press, 2007) and Running Again in Hollywood Cemetery (University of Central Florida Press, 1988). Smith is the recipient of the Carole Weinstein Poetry Prize, the Guy Owen Award from Southern Poetry Review, and the Theodore Roethke Prize from Poetry Northwest. He is Writer-in-Residence at St. Christopher’s School in Richmond, Virginia.