print preview

print previewback EMILIA PHILLIPS

Review | Songs for the Carry-On, by Steve Scafidi

Q Ave Press, 2013

|

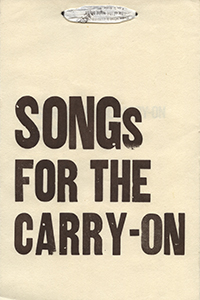

Steve Scafidi’s Songs for the Carry-On looks rustic: on broadside-length rough-cut cream paper, knotted at the top by a raffia-like ribbon, and titled in blemished chocolate-colored type. No name appears on the cover; inside we find seven poems, set narrowly in quatrains or quintets with alternating indented lines. Q Ave Press must have taken to heart historian Lawrence Wroth’s warning that, “To love the contents of a book and to know and care nothing about the volume itself . . . is to be only half a lover.” The poems’ regularity—their forms’ visual balance—coupled with the volume’s design, elevates the act of reading to aesthetic immersion. Both the volume and its contents suggest fine hand-craftsmanship, perhaps with a nod to Scafidi’s work as a cabinetmaker, and resist contemporary publishing not only in its look but in its limited availability. The fact that Q Ave Press’s website makes no mention of Songs only adds to its appeal as an old-world object.

With the exuberance of Bert in Mary Poppins, tempered by Virgilian bucolics, Scafidi insists: “freedom is the rule.” Although short, the chapbook feels expansive as it “dips us and leans,” dancing us “here in between” Jabberwocks and “The Great Fantastic,” a “Door in the Field.” Perhaps one of the most joyous collections in recent memory, Scafidi’s chapbook appeals to the reader’s sense of whimsy:

Hurray for the gizmo and the blue sleeve

of sleep. Hurray for the honeybee

and the rocket flaring in the mind

of the bee. Hurray for the ninety-nine

new kinds of flying through the airninety-nine nights of ninety-nine

dreams introduce to the very young

sparrow asleep in the egg.

For a moment, this poem recalls the marvelous images and sing-song rhythms of children’s verse; the repetition and rhyme sweep us up in their quick current. One might even feel giddy reading these lines, but soon the poem dives into darker waters—“Freedom is a word you can say / only once in your entire life.” Later, the poem evolves into an almost chant-like cadence:

Walk

to Kilimanjaro, walk to the Nile,

walk to where the dead aren’t deadand never were—so hopeless is this place

that is not paradise and never was.

Although Scafidi shifts the content of the poem from the Arcadian honeybees and the “sparrow asleep in the egg” to the “dead” and the place “that is not paradise and never was,” his language never slips into heavy rhetoric. Instead, the drum-like rhythm of “Walk / to Kilimanjaro, walk to the Nile” allows us to not simply read but feel the poem, as with bass-heavy music.

Elsewhere in Songs, the experience of understanding a poem relies on another kind of feeling, intuiting tone. In “El Bastardo!,” the most comic and fantastical of the poems in this book, we hear an Anglophone’s case for learning Spanish:

If I could speak just a little Spanish—uno

petito amount—you would be

astonished. The great arsenic lobsters

of Federico Lorca would rain down

from the blue sky and the angeland the muse would be consumed and

if I spoke Spanish the duende would

rise from the earth clubbing death

to death with a stick in its hand.

Language defeats even mortality here, a claim both dubious and waggish. With more austerity, Scafidi writes that language provides “all the hidden meanings // of all the secret things” and illuminates everything “just outside / [one’s] periphery” so that it becomes “clear and shimmer.”

Language decodes experience and gives it meaning and luster, but it can also provide comfort, as in the title poem—

In the minute and a half it takes

for a plane to fall from the sky . . .—there is still

a moment or two in the chaos of

gravity to say something—it’s OK—It’s OK.

Scafidi reminds us, however, that although “We / like to think we know some things,” “the less we know / the better we feel about everything,” a sentiment echoed in the invocation: “Let the impossible sing. Let all be dumb. / Let the ant dance under the giant crumb.”

In Songs for the Carry-On, language leads us to exuberance, inhabits us like music, comforts us in grief and fear, and bamboozles us into ignorant bliss. If anything, the chapbook revels in language and its possibilities, and in that way the poems become a kind of ars poetica, one that recognizes breath, not words, as the base textile for all poems, as “Breath carries us and we fall away.” ![]()

![]()

Steve Scafidi is the author of The Cabinetmaker’s Window (Louisiana State University Press, 2014), For Love of Common Words (2006), and Sparks from a Nine-Pound Hammer (2001), which won the 2002 Levis Reading Prize from Virginia Commonwealth University. His poems have appeared in The American Poetry Review, New Virginia Review, Southern Poetry Review, The Southern Review, and elsewhere.