print preview

print previewback ROBERT RUBIN

Camelot, after Fifty Years: Remembering Louis D. Rubin, Jr.

A memorial address delivered February 9, 2014 at Hollins University

I’ve enjoyed hearing about how productive my father’s years at Hollins were. I couldn’t help noticing that he started teaching at Hollins in September of 1957, and I was born in July of 1958, so if you work back nine months from my birthday, he appears to have gotten to work quickly.

My earliest memories are of growing up on Faculty Row in the 1960s. I can date two of them. One is seeing bumper stickers for Jake Wheeler’s unsuccessful campaign for Congress in 1962. I was very impressed when his kids handed out bumper stickers to all the rest of us faculty brats, as we were known—it was a design that featured a ship’s wheel, and the slogan “Wheeler for Congress.” When Jake lost badly to the incumbent Republican, Richard Poff, I was very disappointed; in fact, for the next several years, whenever I saw Jake leading a group around on campus, I would shout out, “Hi, Mr. Wheeler! I’m sorry Poff beat you!” Which he no doubt appreciated greatly.

The other early memory that I can date, and I can date it precisely, is from 1963. It is, in an odd way, connected to the reason we’re gathered here today. I was five, and was playing in the front yard of our house on Faculty Row with my best friend at the time, and next door neighbor, Mike Hanna. We saw Mike’s older sister, Tad, walking up Faculty Row from the bus stop, which was down by the old infirmary building near Route 11. This was unusual, because normally Tad didn’t come home from school until late in the afternoon. And she was crying, which was even more unusual. When we asked her what was the matter, she said that President Kennedy had been shot, and that they’d closed school early that day and sent all the children home. I ran in to tell my mother, and found that she was already watching the TV news.

|

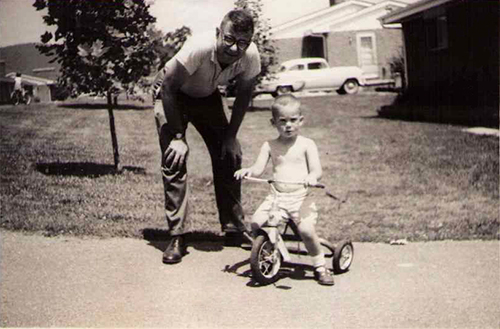

| Louis D. Rubin and neighbor Richie McGuigan Photo by Eva Rubin |

Most of the people my age, and older, can remember where they were when they got the news that day. Most of those younger than me, even my brother, don’t remember it. It’s something of a generational marker, a memory that marks the end date for inclusion in the Boomer generation. Do you remember Kennedy’s death? Okay, then: we can talk. I’ll come back to this memory in a minute, and explain why I think it’s relevant to my father and his work and life. But, if you’ll indulge me, I’d like first to talk a little about what it was like being a kid here on the Hollins campus, and some memories of him here.

- I remember visiting him at his office in Bradley Hall, where he would let my brother and me put our voices on his Dictaphone, which used cylinders of red acetate film on which to record memos.

- I remember how he’d draft his students as our babysitters. Certain ones were our favorites. My brother and I probably have a higher percentage of well published babysitters in our background than most people.

- I remember him printing documents on the letterpress he installed in our basement—the Tinker Press he called it—and getting printer’s ink all over the white dress shirts he wore to teach in, which infuriated my mother. She was a good illustrator, and would draw large pictures of sad looking ink-stained shirts, with word balloons that said, “I was a good white shirt.”

- I remember going to watch him and my mother, who was also on the faculty, parade by in the cap-and-gown procession, along with students who were dressed up in spring finery for the annual May Day pageant.

- I remember his students dropping by in wild costumes trick-or-treating at our house on Halloween.

- I remember him ordering me one day to run around to the back of the house where his printing press was and fetch the “machine” he’d left inside the back door. It wasn’t a “machine”; it was my first bicycle, red and silver, with training wheels.

- I remember, as an eight-year-old, being drafted for a Faculty Follies skit, where a Hollins student goes to a giant-size slot machine to pull the lever gambling on her cotillion date—her options are, I think, Washington and Lee, VMI, and Roanoke College—and when she chooses W&L, out pops me, holding a balloon and sucking my thumb. Cue uproarious laughter.

- I remember practices for the faculty’s Dixieland combo, the Hollins Hambones, in our basement. We were only allowed to sit at the top of the steps and listen.

Those are a child’s memories, and they’re pretty idyllic. Make no mistake: Hollins was an idyllic place to grow up. We faculty brats mostly had the run of the campus, and were made much of by students and staff alike. These days, we have our own Facebook group, and sometimes post photos and memories there.

But our family didn’t stay at Hollins. We moved to Chapel Hill in 1967, and Chapel Hill was where I grew up. My memories of Chapel Hill are much more equivocal than those of Hollins. If Hollins was idyllic, Chapel Hill was the real world, with all its hard lessons. Louis had moved on to a major public university where he had the chance to shape the scholarly agenda, where he could work with doctoral-level students and where his teaching load was lighter, permitting him to do more research and writing plus less undergraduate advising and committee work—an endowed chair, ambitious scholarly projects, and so forth.

With that in mind, at first glance, it might seem a little odd that we’re here today, at Hollins, honoring Louis’s memory, when in fact he was only on the campus for ten years, and then left Hollins behind, going on to supposedly bigger and better things.

|

| Back row: Chauncey Wood, John Garruto, John W. Aldridge, John Moore Front row: Irene H. Chayes, Louis D. Rubin, William Golding, Lex Allen Photo first appeared in Spinster, 1962 |

To be sure, he accomplished a lot when he was here, including founding the creative writing program. But by now the always gracious Richard Dillard must be heartily sick, at some level, of hearing the periodic tributes to Louis, when it’s Richard and his colleagues like Jeanne Larsen and Cathy Hankla who have done the heavy lifting over the last forty years, who have made the program famous, who have overseen the transition to an MFA program, and the expansion into other writing disciplines. And who could blame them?

Yet when you think about it, it all makes perfect sense. Louis left Hollins in the spring of 1967, just before the summer of love, and the Monterey Pop Festival, and Hair, and “If You’re Going to San Francisco.” The next year would see the Beatles’ “White Album,” the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the riots in Chicago, the rise of the counterculture, the deaths of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, the appearance of Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern, the reemergence of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan’s election as governor of California, forced busing in the South, and on, and on. In the battles of red and blue America of today, we’re still living with the repercussions of those years and the changes they wrought.

|

| The Hambones: Chauncey Wood, William Carter, and Louis D. Rubin |

All of this change did not leave Hollins untouched, either. Those May Day celebrations that I remembered? When the faculty processed and the students dressed up, and the May Queen and her court of virgins—well, at least they were supposed to be virgins—danced around a giant, erect pole on the quad? I mean, really? Was that going to survive the arrival of late-’60s- and early-’70s-feminism? I don’t think so. Was the idea of going to college to get educated before getting married and settling down to raise a family going to remain a sustainable model for the institution? I don’t think so. Was a system going to remain unchanged in which a mostly male faculty would be there to paternalistically advise Hollins women about what to do with their lives? Indeed not. Was the very notion of a private women’s college, and its relevance to the modern world, going to go unchallenged? No. And what was going to happen when graduates left Hollins behind and encountered sexism, and glass ceilings, and the demands of balancing professional and personal lives, and changing sexual mores and roles?

Maybe Louis left Hollins just in time!

|

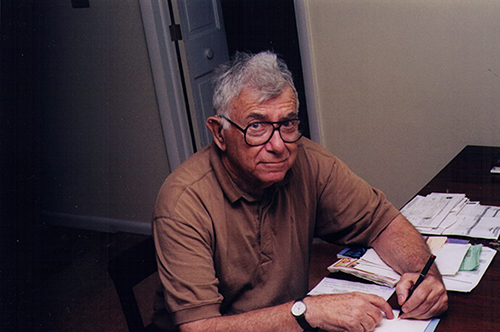

| Louis D. Rubin Photo by Robert Rubin |

The weekend in November on which Louis died was the weekend when the news media began commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of President Kennedy’s assassination. (See, I told you I’d get back to it.) As we were dealing with his funeral arrangements, and answering calls and emails about Louis’s life, the weekend news shows were revisiting the events in Dallas, 1963, and the end of Camelot.

Of course, we now know that Camelot wasn’t really Camelot. We know that Jack slept around and cheated on Jackie. We know some of those adorable Kennedy children grew up to live distorted lives in the shadow of the departed president. We know that Jack had some sleazy friends. We know that there were a lot of screw ups and might-have-beens and never-weres. And yet . . .

And yet as historian Robert Dallek said on CBS’s Sunday Morning, which devoted a whole program that weekend to the anniversary of the shooting, there was something true at the heart of the Camelot myth. It really was a time when we believed, and when everything seemed possible, and when many great things were started. The fact that Kennedy was cut down just when it all seemed within reach did not, ultimately undermine that sense of possibility, or end it—it underlined it. He was not the change himself, he was a symbol of change, a martyr for change, if you will. He spoke to a generation, but in the end it was the generation, not the president, that made the change real.

The students who moved through Hollins when Louis was here were the students of that generation, the generation of Camelot, in a very real way. The freshmen who arrived on campus with Louis in 1957 were just twenty-three or twenty-four years old when Kennedy was killed in 1963, and perhaps planning to volunteer in the newly formed Peace Corps. The seniors who graduated the year Louis left had been freshmen in November of 1963 when Kennedy went to Dallas. It was a time when roles were changing and doors were cracking open and light was shining through them. In believing in those students, in showing them their strengths and their abilities in that new light, in pointing them toward a life of ideas and engagement that they maybe hadn’t considered, Louis was only an agent for the change. They, however, were the change. They went out and made the change happen. The wonderful writers and editors and scholars that Hollins produced during those years were themselves the change. They may look back on Louis, and Hollins, with gratitude, but they were the ones who made their new lives in a new America happen.

|

| Clockwise from bottom left: Louis D. Rubin, Eudora Welty, Harry Duncan, Cleanth Brooks, Lewis Simpson, Francis Fergusson, Morton Weisman, Allen Tate, William Jay Smith, Joseph Frank, and Howard Nemerov Photo first appeared in The Sewanee News, March 1975 |

To be sure, Louis’s support and guidance for his students was very real, and he continued to encourage and support them throughout his career. But he was taken away from Hollins in much the same way that Kennedy was taken away from America, and we are here today because what we remember was the promise and possibility he represented rather than the hard work of actually achieving those promised things.

If Louis had stayed at Hollins into the ’70s and ’80s and ’90s in the way that John Moore and Lex Allen and Jesse Zeldin and others who joined the English department in the ’50s and early ’60s did, perhaps we wouldn’t be gathered here today; perhaps Louis would have come to be taken somewhat for granted, just another beloved professor who grew old while his students remained always energetic eighteen- to twenty-one-year-olds. Maybe he would, fairly or unfairly, have come to be seen as just another part of Hollins, as unchanging as the millstones on the quad. Maybe on a certain level, he recognized that, and it’s part of why he moved on to UNC, and why, after two decades there, he moved on from UNC to Algonquin Books.

Louis loved that sense of possibility, of potential, of “what if?” As at Hollins, the thing that made his work at Algonquin so remarkable was his vision of the possibilities, of the future, of helping writers get started. He never wanted to become a guardian of the way it had always been done, or a gatekeeper to membership in the establishment. He wanted to open doors, not close them.

|

| John Barth and Louis D. Rubin in the Green Drawing Room Photo first appeared in Spinster |

Hollins will always be my childhood home, and my father will always be to me not the mentor with keys to the treasure chests of language and literature and the world of publishing, but rather the gruff, somewhat incomprehensible man with the office in Bradley Hall who let me play with the Dictaphone, or who played harmonica with the Hambones downstairs while I listened on the steps, or who cussed when the boat broke down in the summer heat, or who stunk up the house with strong cigars and threw tennis balls for the dog. Nevertheless, I have been touched by the outpouring of affection for him today, and I thank all of you who have come here to honor his memory.

Yet I will leave you with the following thought. I said earlier that Hollins was the setting for my childhood, but Chapel Hill was where I grew up. I wonder if that’s not true for many of his students too—if the powerful feelings that Louis’s Hollins students have for him are, in a way, also the feelings of adults looking back on an idyllic childhood when anything seemed possible, and the whole wide world revolved around that possibility. That possibility was given form and manifested here, working through the agency of Louis, but it remains a place of beginnings.

He certainly took great pride in his students’ accomplishments. Doubtless some of that was self-congratulation—he was only human, after all, and he loved being made much of, and feted and fussed over. He would love this, though he would make some self-deprecating remark about it being just so much fiction, by fiction writers. But I know he loved his students too, just as I know he loved me, and loved my brother, and he loved his grandchildren. More than that, I am certain that he truly admired his students’ accomplishments on their own terms, and deeply respected the hard work that went into making those accomplishments real. For finally he knew that he did not accomplish those things for them. They accomplished them for themselves.

|

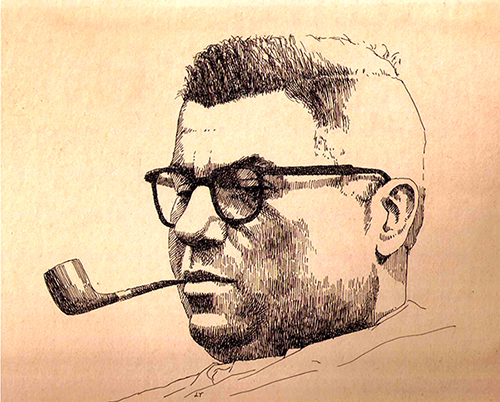

| Louis D. Rubin Drawing by Lewis Thompson, first appeared in The Hollins Critic |

In the end he did leave Hollins, but Hollins was still part of him as he was guiding PhD students at UNC and editing aspiring novelists at Algonquin Books. Hollins changed him too. He did, as I have said, go on to bigger things, but not, I think, to anything better. Saying goodbye to him now means saying goodbye to that part of us for whom this campus was a safe, encouraging place in which to begin our journey into the big, scary world beyond the front gates. I guess saying goodbye to him means that it’s about time we learned to be grown-ups. I don’t really feel ready. Do you? ![]()

![]()

Camelot, after Fifty Years: Remembering Louis D. Rubin, Jr.

In Memoriam: Louis D. Rubin, Jr.