print preview

print previewback CHRISTIAN DETISCH

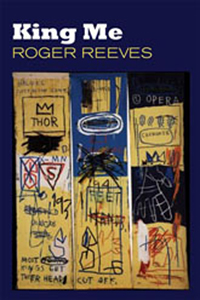

Review | King Me, by Roger Reeves

Copper Canyon Press, 2013

|

At twenty-seven, Thomas Jefferson began removing passages from the Gospels and compiling them into a separate book known as The Jefferson Bible. Notably missing from the book are moments of supernatural phenomena: angels are no longer present at Christ’s birth; the miracles are erased, and the resurrection has been stricken. The composition of The Jefferson Bible suggests that there is something in the world separated from Christ by centuries that cannot reconcile itself with the entirety of the Bible—that certain aspects of experience (particularly the supernatural) need to be deleted to have any moral or instructive value. But in Roger Reeves’ debut collection of poems, King Me, we find it is in the most earthly moments that God is most present; and in the most mystical of occurrences, our deepest humanity. King Me is a collection that turns its head from nothing, not even the possibility of nothingness.

At the heart of King Me beats a desire to reconcile the poet’s identity as an American in all of America’s turmoil and grandeur, its clarities and contradictions. And surely one of Reeves’ great talents is his deftness for juxtaposition. From “Southern Charm”:

Now begins the tradition of the fire hose.

Please, pay no attention to the flag

disappearing into the mouth of a soldier’s

salute. The chickens, goose-stepping

in the backyard, are prepared to peck

each other to death. Charming little children

in the rotunda of a state house holding

sighs below signs demanding the right

to vote Yosemite Sam and James Brown

into office. Bless your heart. Bless

your little heart.

The poem opens with the ominous suggestion of fire hoses used against protesters during the Birmingham campaign, the violence this country enacted upon itself in the sixties during the Civil Rights Movement, mirrored by the sheathed but imminent aggression of the chickens in the yard. Surprisingly, though, we’re next confronted by an image of real innocence, but also of real power: children protesting to elect Yosemite Sam and James Brown into political office. What at first strikes us as a naïve gesture becomes one of reconciliation—a blessing, really—between white and black America, pop culture and politics.

Yet, resolution never comes so easily, even in the space of a poem where disparate ideas and elements can and often do come together in ways they never could outside of art:

Mother’s breath is chapped. She has forgotten

Jesus was born less than a month ago. Therefore

it will be three to four months before he can do anything

about my sister’s mind, the gossiping apples,

the man in dirty boots touching her lips.

In three months, I will watch three men

stretch a girl across a bed like a white sheet.

Here, Reeves’ associative powers take on a darker quality. The mother’s chapped breath and the month-old Jesus are passive and powerless to “do anything / about my sister’s mind”; a girl being stretched “across a bed like a white sheet” embodies a creepy kind of silence and sterility, suggesting both the aftermath of electroshock therapy and a funeral pall. And as this poem—titled “Asylum”—closes out, the resolution offers little consolation:

There will be choking—half-eaten apples

lodged in the pink throats of the geese.

A few dead Adams litter the yard. Mother

ties a trash bag around my wrist, sends me out

to see what has become of God, saying

You’ll need to help your sister this way one day.

The apples transform into the fruit from the Garden of Eden—Adam lying dead in the yard—that asphyxiates the geese, mutes them. God is collected in a trash bag. And if we can’t know what’s become of God, then what hope do we have for ourselves?

What kind of space, really, can God inhabit in King Me? In the poem from which the book derives its title, “Self-Portrait as Ernestine ‘Tiny’ Davis,” Reeves writes:

Call Jesus

down from that cross. Call my tongue a crown

of thorns, a patch of nettles sunk deep in an arm.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Call me tiny, anything small: an acorn

lodged in the throat of a thrush. Choke. A claw

squeezed from the purple head of a flower. Prick.

A hunk of pork butt plucked from the gums

and placed back onto the tongue. Gag. Then swallow.

Feed me. Call my appetite a kind kingdom.

Call me Queen. King me.

The crown of thorns in the speaker’s mouth, which at first stands as a symbol of oppression and—even more crippling for a poet—muteness, is for a moment transformed; but not into an object of greater agency. Instead, it remains an impediment in the throat, a “hunk of pork butt.” What’s remarkable though, is how the speaker finally assents to, rather than resists, what plagues him, and through dropping his resistance becomes a kind of king. But if in the poem’s final gesture—“King me.”—the speaker returns for a moment to checkers and childhood, the allusion isn’t without a certain level of anxiety. In the notes to the book, Reeves offers comments to his poem “John Henryism,” the title coming from the name of the phenomenon charted in “psychological studies that investigate the premature death of educated black men.” Childhood becomes a mere precursor to tragedy.

Surely, Martin Luther King, Jr. also lives in these lines: as a leader of the civil rights movement, as a minister, as a man assassinated for his message and magnanimity. Indeed, in the world of King Me, “most young kings return home without their heads,” and to be crowned a king, to bear a message both great and disruptive, is to die. If the speaker invokes MLK, he also invokes Christ as king, the body broken on a cross—our fragility:

Yes, the body as benediction.

The body tattered at its own behest. Yes the body,

the body—but what should be done with these two men

braced against the bare bark of a tree as if nailed? What

should be done when one church is being built around another?

Even as a benediction, a blessing, our relationship to our body and the bodies of others is still complicated and deeply fraught. What recourse do we have when we witness our own destruction brought down upon ourselves? How can we live compassionately when we, more often than not, are the cause of our own suffering? “How else / Shall ruin announce itself if not in one body touching another?” asks the speaker.

In his essay “Notes on Poetry and Religion,” Christian Wiman writes:

I don’t think you can spend your whole life questioning whether language can represent reality. At some point, you have to believe that the inadequacies of the words you use will be transcended by the faith with which you use them. You have to believe that poetry has some reach into reality itself, or you have to go silent.

If our options are split between silence and expression, poetry and the void, Wiman clearly positions himself with poetry. Christ at the height of his suffering begins reciting poems—My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me? Not as if poetry could assuage his pain, but almost as a gesture of staving off the silence. Reeves, too, at first offers an echo, depicting a “body made to sing even as it is shattered,” but soon changes course in “Our Little Diorama of Argentina (Plaza de Mayo)”:

If you think this is merely a metaphor, a cool turning

of the mule away from the disaster of language,then you have never found your brother in a car,

his head pierced by a piece of metal he lodged there

with a bang. You would want an exchange, too. Coolor uncool. . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

He’s back even as I build this diorama of the Plaza de Mayo.

Like the women circling the green muscles of a horsethat stands atop a casket in the municipal parterre,

unable to locate their dead, I, too, having lost

faith in silence have placed my faith in silence.

Here, metaphor is at once an exchange and a “turning . . . away from the disaster of language,” the stark reality of discovering the suicide of the speaker’s brother and the silence that inhabits that space. But the silence in these lines doesn’t function as a void so much as the speaker finding a means back to expression. All poets—anyone who’s blessed and cursed to participate in “the disaster of language”—have felt how inadequate language can be up against experience, how like helium it rises against the lead-heavy reality of suicide, genocide, mental illness. Losing faith in silence, however, seems like a very different, much more serious, problem altogether. And yet, the resolution offered in those last lines—to put faith in the very thing that at first annihilated that faith—which at first may seem like no resolution at all, strikes me as the book’s great achievement: one silence (one of shock and fatigue) exchanged for another (one of reverence and acceptance).

This acceptance should not be read as placid or complacent, however:

And what if this goes on forever—our ours?

Our drafts and fragments? Our blizzards and our cancers?

Then let us. Then, let us hold each other toward heavenand forget that we were once made of flesh,

that this is the fall our gods refuse to clean with fire or water.

The book’s final move is not one of consolation but of contingency. Our drafts and fragments, blizzards and cancers persist, and the only synthesis and resolution they find is their irresolution. We are not made clean—our gods refuse to clean us. What we have left, then, is ourselves, holding each other toward heaven.

In a letter written in prison, Dietrich Bonhoeffer asserts that “the God who makes us live in this world without using him as a working hypothesis is the God before whom we are ever standing. Before God and with him we live without God.” And this is the God of King Me: one who has us turn our eyes toward each other—our genocides, suicides, lynchings, half-eaten apples, children, geese. If we come to any kind of reconciliation with the world—with our identities—it is a tenuous reconciliation, but one that we make only when we, like the speaker of these poems, can assume everything, even the possibility of forgetting our flesh. ![]()

![]()

Roger Reeves’ collection of poetry King Me (Copper Canyon Press, 2013) received the 2014 Levis Reading Prize. His poetry has appeared in Ploughshares, The American Poetry Review, Boston Review, and Tin House, among others. He is the recipient of the 2014–2015 Hodder Fellowship, the 2013 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and two Bread Loaf Scholarships. He is assistant professor of poetry at the University of Illinois in Chicago.