print preview

print previewLOUIS DRAPER | The Character of Everyday People

A Conversation with Nell Draper-Winston

“I am a photographer rooted in the humanistic tradition. My influences have been W. Eugene Smith, Roy DeCarava and Dorothea Lange. My goal and aesthetic are one and the same.”

—Louis Draper (1935–2002)

On Wednesday, February 4, 2015, Nell Draper-Winston, sister of photographer Louis Draper, joined Virginia Museum of Fine Arts curator Sarah Eckhardt and Candela Books + Gallery founder Gordon Stettinius, to talk about her brother’s life and work in New York, and their family’s Richmond roots.

~

Sarah Eckhardt: The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is happy to have you here, and we thought this would be a wonderful opportunity to have you tell us about your brother, Louis Draper, and about his life here in Richmond and then in New York. This gives us a chance to record that history so that we have it as a context for the photographs that we’ve acquired here at the museum.

Nell Draper-Winston: Well, he was—we were—born here in Henrico County. And he attended Henrico County Schools—Virginia Randolph High School. Our dad was—I guess you would call him—an amateur photographer. He just went around snapping the kids in the neighborhood. Sometimes the parents would ask if he would take family photos. He tried to get my brother interested in it, but Louis was not interested in photography. All he wanted to do was play basketball and baseball. That’s it.

![Hansel Draper, [Nell Draper and Louis Draper] Hansel Draper, [Nell Draper and Louis Draper]](images/historical/draper_family_001.jpg) |

| Hansel Draper, [Nell Draper and Louis Draper] |

But when he entered Virginia State College—it was College then—Dad gave him a camera. And later, during his time there, he joined the camera club. He said, “Well, I have the camera; I might as well do something with it because Dad paid a lot for it.” So he went around photographing the different events on campus. One day, when he went to his dorm, he entered the room and there was this book—an open book—on his bed. He said, as he approached it, the photos just seemed to jump out at him, and he said they were so powerful that he just couldn’t put the book down. It was called The Family of Man.

That was when the bug hit him. “Got to go to New York,” he said, “and pursue a career in photography.” So in ’57—1957—he traveled to New York. He freelanced for a while and lived in the Bowery and different places until he could get himself situated.

He attended Thomas Edison College, received a BA degree there, and later joined workshops. He just wanted to get involved in photography as much as he could. He studied under Harold Feinstein, and W. Eugene Smith, two of the legends of photography. Then he met Langston Hughes, who had purchased a brownstone from his aunt. He had different boarders there, and Louis was one. Louis said that, at two, three, four in the morning, he could hear Mr. Hughes typing away, and he would think, “I guess Mr. Hughes is typing another poem or another play,” and he’d turn over and go back to sleep. Later Mr. Hughes became his mentor. By Louis being young—nineteen, twenty, maybe twenty-one—sometimes when he would take photos, people promised to pay, but didn’t. So Mr. Hughes would either write to them or call them and remind them that they owed Louis Draper for the photos that he had taken.

![[Portrait of Langston Hughes], c. 1960 [Portrait of Langston Hughes], c. 1960](images/candela_blog_sized/draper-0040-langstonhughes.jpg) |

| Louis Draper [Portrait of Langston Hughes], c. 1960 Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

So he went around, just trying to take photos of people. He loved just photographing people doing their everyday activities. He traveled to Africa, Moscow, Germany, Paris, London, and exhibited there. In fact, after he passed, a lady from Germany came over—she didn’t know that he had passed—and asked if he could come over and take more pictures there for them. The people at Mercer County Community College, where he taught, informed her that he had passed.

He photographed several notable people who we would call celebrities: Langston Hughes, Michael Jackson, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. He was a jazz enthusiast, so he photographed Miles Davis, John Coltrane. Also the civil rights activist, Fannie Lou Hamer. He stayed at her home for a week, and he said she and her husband were just—just great. He photographed her, and it was during her time in the Democratic Convention when she spoke to the people.

He said that he loved photographing notable people, but his main joy came from capturing the character of everyday people through his photography. He continued to say that.

He would come home, and people in the area didn’t know about what he was doing. He would just come on and say, “Oh, I’ve got to see Mrs. Anderson while I’m here. How’s so-and-so doing?” And he would go to see them. After he passed, everyone was saying, “I didn’t know Louis was doing the things that he was doing.” I began to think that he was known nationally and internationally but not in his own hometown. And so that was why I decided to just try to give his craft—his work—some exposure here in the Richmond area, in his hometown. That’s how all of this got started.

![[Jackie Onassis and Norman Mailer], c. 1950–90s [Jackie Onassis and Norman Mailer], c. 1950–90s](images/candela_blog_sized/draper-0136-jackieoandnormanmiller.jpg) |

| Louis Draper [Jackie Onassis and Norman Mailer], c. 1950–90s Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

SE: When you called the VMFA and brought his work to my attention, I had not known anything about Louis Draper. As I looked at his work, it spoke for itself. It was just so strong, and then to have the Richmond story about his growing up here—the work and the story together were something that we couldn’t pass up.

Gordon Stettinius: In the year and a half that I’ve been working with you on the archive, there are two rewarding things; one is watching how you are so plugged in to creating a legacy for Louis. It’s something that’s really endearing to me. The focus on making sure that kids see the work and that Richmond understands who he was is something that I feel glad to be a part of.

NDW: Thank you.

GS: Then on the flip side, as a photography enthusiast, there’s just so much there in the archive to acquaint myself with. Every once in a while, I have occasion to go in to the negatives because somebody’s interested in a specific subject, and there is just a wealth of material, a wealth of thought behind this gentle man and his attention to photography, the craft and education—his sense of responsibility with the students. His work has been impactful to me, at times—poignant, at times—sometimes it’s just expertly crafted. But it’s actually a fairly serious collection of work. It’s got street photography and abstraction, and some timely work. That he just happened to have been a tenant of Langston Hughes? That’s amazing, but a little bit fortuitous.

But it’s clear he made a lot of headway as a photographer, and I’ve learned, slowly, that he was a really generous individual as well. And the students, their affection for him, has come to me via email and letters. I should have known as much because you are incredibly generous—and a selfless spirit as well.

NDW: Thank you.

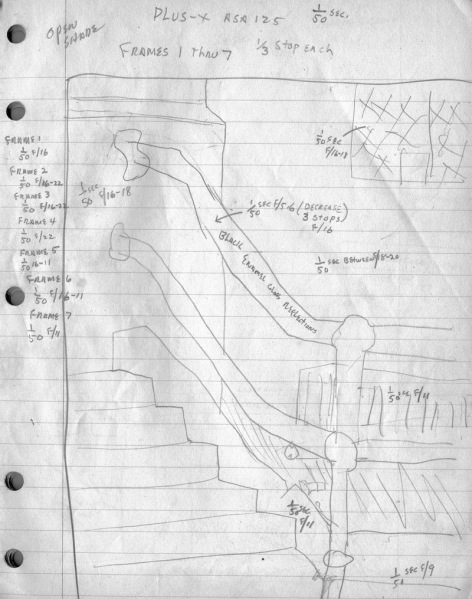

|

| Here is a page from a photography class notebook of Draper’s, circa 1968. He is practicing planning what his shutter speed and aperture settings should be for each area of a potential photograph. The approximation gets based on the reflective qualities of the materials in the scene and the shadows being cast onto each area. Draper has notated each possible surface with the required shutter speed and aperture setting. He then could pinpoint an average setting for the entire photograph. —Gordon Stettinius, The Louis Draper Project |

GS: It’s been very cool to see an outpouring of attention and interest in his work because of the person he was as well as the photographer.

NDW: Well, thank you. He was so very passionate about his work. And at his memorial at Mercer County Community College, his students said just what you said. He was a nurturing type of person, and he wanted them to succeed. In fact, one of his students became head of the department after he left. They had interviewed quite a few people, and they said that none of them had the depth that this young man had. And so he, Eric Kunsman, became the head of the department after Louis.

SE: Gordon pointed out how you are such a nurturing spirit as well. Maybe we can go back a little bit chronologically, because I think it’s important to have a sense of who you are and who you’ve been in the Richmond community too, along with some of the things you did, and who your family was. Would you mind talking a little bit about Virginia Union University in the early 1960s and some of the things that mattered to you? I’m sure you were telling your brother about what was going on.

NDW: Yes. Well, our parents were very, very caring. Also, we were a close, close family. We played board games together. Got out there and played baseball. Before you knew it—the neighborhood kids, everybody was there in the yard playing. They taught Louis and me family values of love and respect for one another and for others, and that kind of carried over.

Louis attended Virginia State College—it’s University now—and I attended Virginia Union. And you mentioned the sixties; of course, you are alluding to the civil rights portion of it. We did meet Dr. King. We had, each year, an annual week of prayer, and this particular year, Dr. King was the speaker. And he was there four days, I believe, that week. I remember some of his sermons, and he, to this day, was the most eloquent speaker I have ever heard, and I’ve heard a lot of speakers. I remember one of his sermons, “Going Forward by Going Backwards: How Do You Know Where You’re Going if You Don’t Know Where You’ve Been?” That kind of stuck with me.

And of course, as you know, the sit-ins were going on at that time. Several of the students at Virginia Union sat in at Thalhimers department store, amidst the throwing of ketchup on them and other things. Well, we know what transpired after that. There were groups that would go in to sit—sit-in—and the point was to bring attention to what was going on. And we for three weeks rehearsed what we felt might happen to us. Whether we’d get back home or not, we didn’t know, but we did everything to each other that we thought the police would do or spectators would do to us. The only thing that we didn’t do was spit on each other. We stopped at that point. But we pushed each other down. We just did the things we thought would be happening.

|

| Robert N. Anderson, Jr. Protest ouside of Thalhimers, February 22, 1960 Anderson Collection, Valentine Richmond History Center |

The first group, thirty-four students, went in, and they were arrested. Now, had they not been arrested, we would have been the next group to go in—so it was just thought out like that. But they were arrested. So what we did—our group—we protested; we boycotted Thalhimers. And we were naturally afraid. People asked, “Were you afraid?” Of course we were afraid, because there were the police there with the dogs, and they, a couple of them, would do like this, you know. I remember when I was a child they used to say “Sic ’em!” Sic ’em? That was the attack command. But they didn’t say that; they said something else, and then they would do like this. But we were trained to go to this point. We couldn’t go past. We had to go and turn around and come back, you know. We knew exactly where the line was—we couldn’t step on this crack, you know, in the sidewalk, so we were blessed that we were not hurt.

Thursdays were the ministers’ day. We would picket every day except Thursday. And I remember one rainy, rainy Thursday, and my pastor was in his late seventies, early eighties, and he was out there with his umbrella picketing Thalhimers, and I was never so proud of him or my church, as at that moment. We all felt that if we could get Thalhimers to, to crack, to come around, then the other stores would follow suit—Grants, Woolworth. Because Thalhimers was like the Gimbels of New York. Thalhimers and Miller & Rhoads were like Gimbels and Macy’s. And so that was the rationale for it.

SE: And that’s what happened, right?

NDW: Yes

SE: It took just over a year, about?

NDW: Yes.

|

| Robert N. Anderson, Jr. Protest ouside of Thalhimers, February 22, 1960 Anderson Collection, Valentine Richmond History Center |

SE: A solid year of picketing, and if I remember correctly, Thalhimers started to negotiate, and then the other stores . . .

NDW: Yes. They just followed suit.

SE: Fell in line. But, it took a long year.

NDW: Yes.

SE: So you picketed regularly?

NDW: Yes.

SE: Throughout that year?

NDW: Yes. We had certain times.

SE: A schedule.

NDW: Yes, we did.

SE: And so it would have been, if I remember correctly, about two years after that that Louis Draper founded Kamoinge, the first African American photography collective, in New York.

NDW: Right. Yes.

SE: I think that’s 1963.

NDW: That’s ’63, correct.

SE: Because I think that the sit-ins started in ’60 and the picketing ended in ’61, about.

NDW: Yes

SE: So do you have any memories of your discussions with your brother? Did he talk with you at all about Kamoinge at its beginning?

NDW: Kamoinge. Yes. He spoke with me about that. I met some of the Kamoinge group. You know, we would go up—our parents and I would go up just to see him, and we met some of the members of the group.

SE: I’m remembering that in his notes he seemed to think about the founding of Kamoinge to be very much in the context of the civil rights movement. The members of Kamoinge were supporting one another in their work, but they were also very conscious that they were producing images that might counter some of the images in the mainstream press.

NDW: Yes, and they joined forces because many times the main press left them out as photographers. So they came together as a group so that they could depict African American life.

|

| Kamoinge Workshop group photo, NYC, 1974. Draper front row and center. The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

GS: Did Louis Draper ever make an invitation to you or to your family to come see what the members of Kamoinge were accomplishing? Because they did put exhibitions up that brought critics and curators to galleries in Harlem.

NDW: Yes, we did see some of their displays. And I remember Louis had a display at the Peddie School, and my mom and I went up. But not too long after that our dad became ill and it became increasingly difficult to get up there, but prior to his illness, Dad went up for a week. Louis was living in the Bronx then, directly across from Yankee Stadium. So needless to say, they went to some games there. I was glad that Dad had a chance to just get there, and that he and Louis had a chance to be together. But I met the people. Sometimes it was at social events, and then it was years before I saw them again. We might have telephone conversations, but I really didn’t see most of them until Louis passed.

GS: Did you have a sense of him as a working photographer? Did you ever visit him when he shared a studio? I believe he worked out of—

NDW: Tony.

GS: Tony’s studio, Tony Barboza?

NDW: We never got to Tony’s studio. Dad may have because he was there for a whole week. But I never saw Tony’s studio; I can’t recall seeing it anyway.

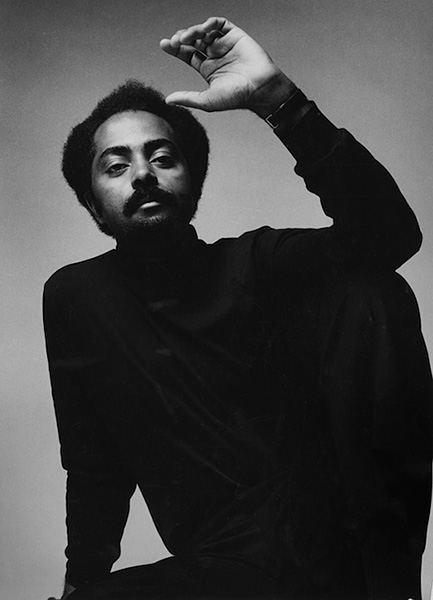

GS: My impression from the large collection of work is that your brother had a work-a-day studio aspect where he did headshots for people, or portraits to give to loved ones—or he has a whole lot of work that is essentially studio portraiture. It seems to represent, maybe, a significant portion of his early work. Some editorial work, as well, I guess, that had him traveling, and then some studio work, which he seems to have excelled at as well.

|

| Louis Draper Hughie Lee Smith, c. 1950–90s Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

NDW: Right. I recall when he was there with Tony. I think Louis was his assistant for a while, but as I said, I don’t recall being at that studio. I think it was on Eighteenth Street if I’m not mistaken.

Yes, Shawn, and Buford, you know, quite a few in that herd. Randall, yes. Robinson, I don’t . . . well, I did meet him after Louis’s passing, but I didn’t know him that well. And we’ve spoken on the phone a couple of times. Ming Smith, see, at that time, was the only woman in the group.

GS: Pretty interesting.

NDW: And another woman, Dorothy, but later. Different. But the relationship still exists. I still speak with Buford, Tony, Herb, mostly Herb.

GS: And Kamoinge still exists.

NDW: Kamoinge, yes.

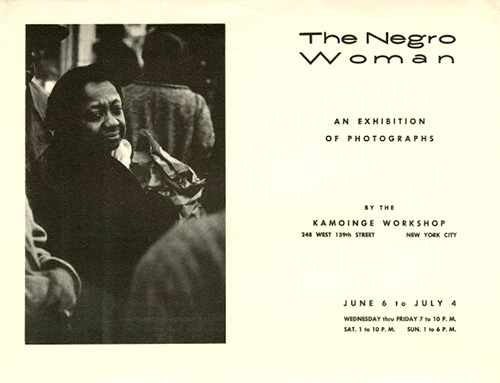

|

| Poster for Kamoinge’s 1965 exhibition, The Negro Woman The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

GS: Which is really amazing. They seemed to have linked with En Foco, I believe, somehow got in a collective together that interests and promotes the work of Latin American photographers. They share some kind of promotional relationship online

NDW: Okay.

GS: But Kamoinge’s still . . .

NDW: Alive and kicking.

GS: Yes, fifty years later, which is amazing.

NDW: Yes. Yes.

GS: And it’s one of the aspects, when I circulated Louis’s work to the photo world, that was always interesting, because Kamoinge doesn’t have the recognition that it deserves.

NDW: Yes.

SE: The curator from the Museum of Modern Art knew my reference to Kamoinge right away because they have Kamoinge’s portfolio from the early ’70s, acquired by John Szarkowski; he’s one of those names in photography that helped define the field in the ’70s. I think that the time is definitely right for bringing a renewed focus on what Kamoinge was doing at the time and given that the group is still active.

NDW: Right, yes, it’s good that they’re still active. I’m really happy about that.

SE: From Louis Draper’s papers, we know he wrote so beautifully, at the time they were forming Kamoinge, on their mission, and on some of the troubles they encountered. His notes are so valuable now in looking back at that period.

NDW: Oh yes.

![[Woman in crowd], c. 1965 [Woman in crowd], c. 1965](images/candela_blog/draper-0121_bw_contrast.jpg) |

| Louis Draper [Woman in crowd], c. 1965 Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust (only documented photograph from Kamoinge’s The Negro Woman exhibtion) |

SE: I have a few questions about the work that the VMFA acquired just because it would be nice if you remember anything about them for us. So we acquired thirteen photographs. When was that? Two years ago?

GS: Probably closer to a year ago, a year and a half maybe.

SE: It seems longer than that; it was incredibly difficult to pick because he has such a wide range of images and there are so many beautiful prints, beautiful compositions. Also different things he’s trying to accomplish. He has, throughout his work, images of images in the background.

NDW: Oh yes.

SE: So there will be a person with a mural in the background, or there will be writing in the background, or there will be a poster in the background and he’s so accomplished at this framing, waiting for the person to be at just the right space as they walk, or as they move in relationship to the mural or the writing in the background. Beyond that, he has images of figures, as you know, notable figures, including Malcolm X, and then he has much quieter, abstract images as well. I was trying to get a range of all of those pieces.

Do you remember anything about the Malcolm X photograph? Did he talk at all about that?

|

| Louis Draper Malcolm X, Harlem, 1964 Gelatin silver print 9¼ in. × 12⅝ in. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond National Endowment for the Arts Fund for American Art Digital photo: Travis Fullerton |

NDW: The only thing I remember is that he—I think he was in a class and he had to photograph, what do you call it, light and shadow?

And there were a lot of people in that room. But some of their photos you’ll see only just focusing on Malcolm X, and you might see if a person had a white shirt on—you might see that—but you don’t see the person. Because of that, it was one of my favorites. And you mention Fannie Lou Hamer. Louis had said that he stayed there for a week. And he might take thirty-five frames, thirty-six frames—I think that’s what you call it—to get one. And the day before he left, he said there was just something he wasn’t satisfied with. And Mrs. Hamer was bedridden the last two days that he was there. I think it was her back if I’m not mistaken. And he said when he left, the car came to pick him up to take him to the station, and he had said his goodbyes to her and her husband. She came out on the porch to again say goodbye, and that moment—that was the moment he had been waiting for—he took a picture of her. I said, “Wow, that’s really something.” I mean as he was leaving, the picture that he had been seeking, you know, appeared. I thought it was great. I enjoyed that.

![Fannie Lou Hamer [portrait], Mississippi. 1971 Fannie Lou Hamer [portrait], Mississippi. 1971](images/candela_blog_sized/draper-fannielouhameressencemagazine1_levels_subyellow.jpg) |

| Louis Draper Fannie Lou Hamer [portrait], Mississippi. 1971 Essence magazine The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

SE: And it was the lead image in Essence. He was sent down there by Essence magazine.

NDW: Essence, yes.

SE: And the photo that he had been waiting for became the lead photo for the article. And it’s a really amazing article because it’s an interview with her, so you get a strong sense of her voice paired with the strength of his image.

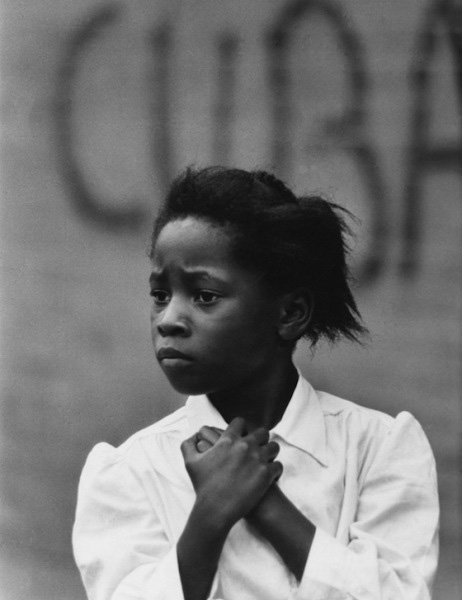

NDW: And another photo that I really like is the girl with “Cuba” written behind her. I just love just looking at her expression because it’s left up to the viewer, in my opinion, to make a decision—“What is she thinking; what’s in her mind?” You can see a little anxiety there, a little fear, you know, a little apprehension. I just love watching the expressions on peoples’ faces, after I heard him say that was his joy, capturing the character of everyday people. So I pay more attention to the photos now, and Cuba girl was one of them. I just love that face, and she has her hands clasped like this. So they’re some of my favorites.

|

| Louis Draper Girl and Cuba (Philadelphia), 1968 Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

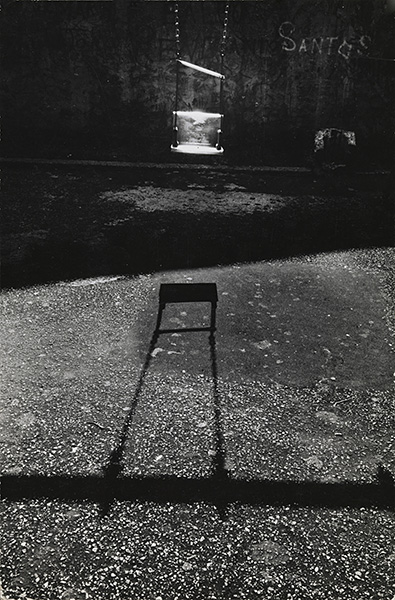

GS: You have the story that is attached to the photo of the swing. That seems to have been a very important one to Louis for a number of reasons, which I’ll let you describe, but the first note that I took of it was that there are so many prints of it with different interpretations and different sizes. It was plainly something that he worked very hard on, so that brought me to wonder aloud to you, and then you told me a story about that image.

NDW: Yes. Again, that was like the Malcolm X image—light and shadow, as the swing is in motion. But we never discussed it; Louis never discussed it with me. I didn’t know until at our parents’ funerals. He placed the photo in the casket of my dad, who passed first, and then he placed it in our mom’s.

And in the background, you can see santos, which I think in Spanish means “saint.” And I’m thinking that he thought of our parents as saints. That’s my understanding of it. Like I said, we’d never discussed it.

|

| Louis Draper Untitled (Santos), 1968 Gelatin silver print 8 15/16 in. x 5⅞ in. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond National Endowment for the Arts Fund for American Art Digital photo: Travis Fullerton |

GS: That gesture is immense.

NDW: Yes

GS: It’s interesting to me how the significance remains with that photograph for what he has vested in it.

NDW: Yes

SE: And that sense of the swing moving, but empty, so that you still have the sense that a person was just in it—

NDW: Yes

SE: Then there’s a lot of reflection in the light, and—

GS: Duality of a really bright area, a really dark area, shadow—

NDW: Yes, so that’s an important photo for me also because of what he thought of it.

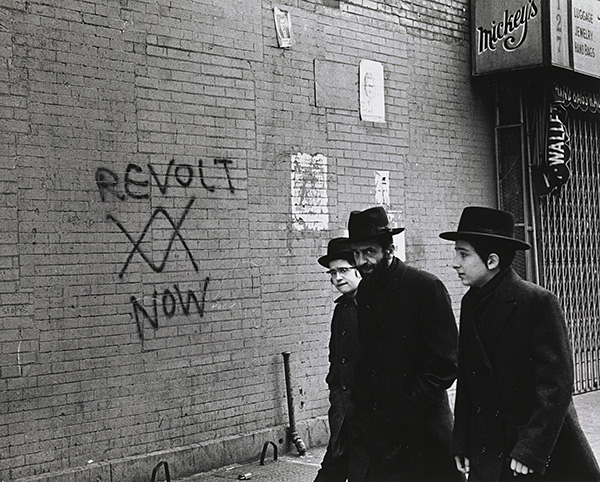

GS: Another one would be the protest image, which I’m not sure if you have a story attached to or not, but it’s one acquired by the VMFA.

SE: It’s the black Muslim protestors on the street.

NDW: Oh, yes.

SE: Well, actually, I’m confusing it with Gordon Parks’ image, which was in Gordon Parks’ LIFE magazine article on black Muslims in 1963, and I think that the image that Draper took is a really similar date, but it’s just two men in suits stepping out. But there’s a police officer between them, and you get this tension and this sense of surveillance, and it’s interesting that two different photographers took somewhat similar photographs. It gives you a sense of how relevant that was at that time.

NDW: At that time, yes.

SE: I don’t know if you remember that one or not.

NDW: Yes, I remember the photo, but we never spoke of it; I just saw that photo in his collection—at University of Virginia—but we never spoke of it.

GS: There was another image where “protest” was written on the wall behind the—

SE: It said “revolt” on the brick wall and there are Hasidic Jews that are walking in front of the wall.

NDW: Yes.

GS: Oh, “revolt,” “revolt”—yes—

|

| Louis Draper Untitled (Revolt Now), 1960s Gelatin silver print 6 15/16 in. × 8⅝ in. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond National Endowment for the Arts Fund for American Art Digital photo: Travis Fullerton |

SE: This is another one that I don’t think we have a date for.

GS: I don’t know that we do. That’s the one print; there’s no indication of title and date on that one.

NDW: Yes, I remember that photo; we didn’t discuss it.

GS: This is another example of him messaging, of having something to say within the context of just editing an image or a frame. Other examples would be the “grow rich” bank sign with the kids playing beneath it; you see a sense of somebody trying to author a thought, as opposed to just observing something.

NDW: Okay, yes, yes.

![[Grow Rich], c. 1950–90s [Grow Rich], c. 1950–90s](images/candela_blog_sized/draper-0217.jpg) |

| Louis Draper, [Grow Rich], c. 1950–90s Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

GS: I think it makes him an active idealist or politically active person. Pretty interesting to see.

SE: Or he just sees a tension in everyday life. As a photographer, you can tell he’s always on, always, always aware of his environment and his surroundings because he’s finding these in unexpected places. I just imagine him walking and then he would just encounter these images. Of course, I don’t know what his practice was like, so I don’t know how long he might have waited. I’m thinking of somebody like, Doisneau, a French photographer; he would find a scene and then he would sit, and he might sit all day and wait for the right moment. I don’t know if that’s how Louis Draper worked.

NDW: I don’t know, because most of his work, of course, was in New York, and we were here in Richmond, but I know we used to jokingly call him “the camera kid,” because when you saw Louis, you saw that camera, and everywhere that Louis went, the camera was sure to go.

So I just don’t know. I know New York has some long blocks. I know he used to walk, walk, walk, walk the blocks of New York, just trying to be ready.

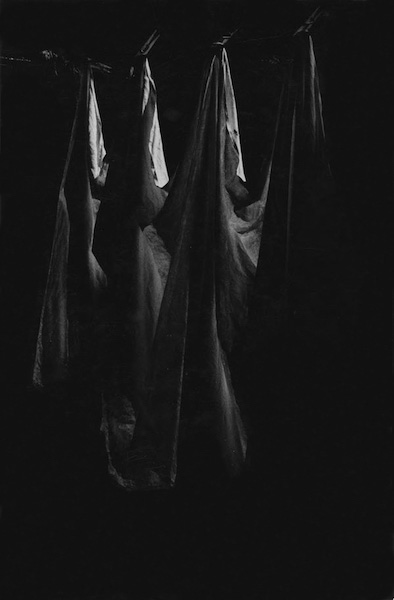

GS: He did have a lot of quiet observer-type images, things that did come from waiting or watching, trying to let something unfold in front of the camera. And he had some images I feel like he was trying to give some intention to. Then he also had some interest in process—not alternative process, but the craft—and he tried to use that in interesting ways with development or printing to dramatic effect. The image I’m thinking about is one called Congressional Assembly, which depicts the sheets.

NDW: Ah, yes.

|

| Louis Draper Congressional Gathering, 1950–90s Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

GS: Congressional Gathering.

NDW: Yes, Gathering.

GS: He’s got the sheets, showing us one thing and alluding to something else. They look like Klan robes to me, and I think that is probably his intent. Did he ever speak to that image at all?

NDW: No.

GS: The intent seems clear, and when we showed his work last year in the gallery, that was one of the photographs that was unto itself in some ways, because it seemed to me purely political. It seemed like something he created, as opposed to watched or waited for as the patient-observer type of photographer.

NDW: Right.

GS: It seemed like a tableau, or a constructed image. Even though he maybe just saw it, he turned it into something.

NDW: Exactly, yes, yes. Louis was always ready to capture something that would speak to whatever the situation was. I remember hearing that—when he was quite young—there was a man, threatening to commit suicide, threatening to jump off a building from a window. The police were there, and they were trying to talk him down with not much success. And a fellow who lived in that same building talked him down. Louis, as far as the police would let him, and then some, was trying to get to that scene, and he did take a couple of pictures. He ran back to the newspaper office, and he said he was out of breath, and he went to the manager, and he was thinking of a—good humor. What do you call it? The word goes from me now—someone who is trying to help their neighbor. Good . . . good . . .

SE: Good Samaritan?

![[Schomburg], 1950–90s [Schomburg], 1950–90s](images/candela_blog_sized/schomburg0071.jpg) |

| Louis Draper [Schomburg], 1950–90s The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

NDW: Well, Samaritan; that’ll do. Yes. That’s better. He thought that’s what the story would be, and this fellow said, “Well, did he jump? Did he jump?” Louis said, “No, no, that’s what I’m trying to tell you! This guy talked him down!” And Louis was going on and on, and the manager said, “He didn’t jump?” Louis said, “No!” And the manager said, “Well, I’m not interested then; if he didn’t jump, I’m not interested.”

Louis was—like I said—quite young, nineteen, twenty, and he was so upset. He told our father, “If I never get a picture, I’m so glad he didn’t jump,” and that could have really stuck with him, or someone who, maybe, weaker, might have said, “This is not for me, I don’t want . . .” He could have given up because of that rejection, but he said, “That’s alright.” So he just put that behind him, and kept going to the next event. But he told me he ran a couple of blocks, and that’s what made me think of New York’s long blocks. . . .

Human interest story. That is what I was trying to think of—

SE: Human interest.

NDW: It was a human interest story. That’s it.

GS: Louis Draper’s connection to Richmond and his family seems very strong. Were there other important relationships in his life, in New York? His work was external; it was a lot about the city and the general people and conditions, and political concerns at large. you hold more of his personal story than maybe I can find in his work. I’m curious about the man in that regard. He was very drawn to people—

NDW: Yes—

GS: Plainly.

NDW: He was.

GS: And the portraits—were the artists in Kamoinge—were they his collective, important relationships? He had great, wonderful, sort of light-hearted images of children, but no children of his own, but he had close relationships with at least one, one—

NDW: Yes, yes. Godson.

GS: Godson.

NDW: Yes, Brandon. And his relationship with Kamoinge was—with the photographers of Kamoinge—was very close, very close.

GS: As a family.

NDW: Yes. And during his earlier times there we had family there who passed. But Kamoinge was his family. And then of course he had other friends that I had heard of and maybe talked with on the phone, but they were his acquaintances and friends.

GS: And he visited Richmond often?

NDW: Mostly during the summer and Christmas, because he taught summer school at various times, so it was cut short a little bit, but he would always manage to get here. I remember he—as I said, he loved jazz—he would come during what was called June Jubilee, and he and my across-the-street neighbor used to take their little chairs, folding chairs, and go out to wherever it was being held, and he loved that. He loved doing that.

SE: That reminds me of the one photograph that we know is in Richmond; it is the portrait of your father that he took in the barbershop on Q Street; am I right?

NDW: That’s right.

SE: Q and Twenty-Ninth, Church Hill.

![[Hansel Draper at the barbershop on Q street] [Hansel Draper at the barbershop on Q street]](images/candela_blog/schomburg013.jpg) |

| Louis Draper [Hansel Draper at the barbershop on Q street] The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

NDW: That’s right. The barber was my mom’s cousin, Billy Alexander, and our dad would go there and Doug Wilder used to visit there because he lived on the next street over at the time. And Dad, you know, Dad was glad. He liked taking pictures and he didn’t mind being in them, so Louis took that of him at the barber shop.

SE: Did both your parents grow up in Church Hill?

NDW: Church Hill, yes, both of them.

SE: So that was a neighborhood that you came back to visit because of family and friendships—

NDW: Yes. We had extended family in Church Hill also. My mom and dad were childhood sweethearts and attended Armstrong High School, which was on Leigh Street and was renamed Benjamin Graves when they built the new Armstrong on Thirty-First Street. I remember my mom said, “Why couldn’t that have been here when we were coming to school?” But they had to come up to Leigh Street to what is now Benjamin Graves. After that, Benjamin Graves was “old Armstrong,” as that class called it, old Armstrong—

SE: Adams and Leigh Street?

NDW: Adams and Leigh. Or where the Bill Robinson statue—

SE, GS: Bojangles

NDW: —is now. Yes.

NDW: So they had to walk across the viaduct—

SE: That’s a long walk!

NDW: And that clock that you see, that you can see over as you’re going south, over the south side. They used to tell time by that clock as they were going there. Yes, that was the way it was.

SE: Do you have any memories of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts when you were growing up? Was this a place that you at all visited, or not?

NDW: No, it wasn’t that available at that time.

SE: That’s one of the questions the VMFA has been asking in establishing a more comprehensive history of the museum. Though it was apparently not officially a segregated space, it was a space where people didn’t feel comfortable, and so—

NDW: Not really available at that time.

SE: That was one of the questions I had, especially in thinking about the VMFA acquiring Draper’s work, and thinking about the history and what the museum meant, or didn’t mean to him, when he lived here.

NDW: To my knowledge, no, he didn’t come here. None of us did. And he left Richmond in ’57, because he knew that he couldn’t get the work here that he could in New York.

SE: And ’57 was about a year after Massive Resistance had begun in Virginia. I’m assuming that affected the general atmosphere, affected his feeling a need to—

NDW: To go.

SE: To go—

NDW: To pursue his career in New York, at least north, but more specifically New York. Because there he’d be able to have the opportunity there, where he wouldn’t here.

|

| Louis Draper Untitled, c. 1950–90s The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

SE: I want to ask you about the story, then, that leads us back full circle to how the archive started—Louis Draper’s papers and the photographs—and how the whole relationship happened between you, Cheryl Pelt, Gordon Stettinius, Candela Books, and the VMFA.

You and Cheryl Pelt first approached me about his work in 2012. You brought some images initially and that were reproductions from Richmond Camera, so I had wanted to see more prints. You then brought some of the original prints, and we went through those, but at the time the archive of work was stored at the University of Virginia library, although they didn’t own it. You told me there was a whole lot more there but we didn’t have access at the time.

GS: Sarah, you recommended that we speak, which we did after some months. I then met Nell and Cheryl, probably the summer of 2012. It took a little while for me to visit the archive in special collections at University of Virginia, and to decide whether or not I was going to get involved, or start working with the archive. When we first met, I saw a collection of work that was really compelling, but it was also eclectic and it had some reproductions—

NDW: I think—excuse me—I think Page Bond mentioned you.

GS: Page Bond, yes.

NDW: We were just going all around, because Cheryl was new to Richmond, and I was new to everything. I didn’t know anything about photography or what to do, and so she kind of represented the the collection. And Page Bond mentioned your name.

GS: Not to do too big of a detour, but having had one archive that I’m representing, a photographer named Gita Linz, I was acquainted with the mechanics of trying to conserve and edit and make a presentation to a curator such as Sarah, and trying to broaden the legacy for a photographer.

Occasionally since that time I’ve had some opportunities to consult on other estates or archives, but when you and Cheryl visited, the whole picture was really incredible, the two of you very industriously representing the work to Heincamp, or to the city hall, or to the state, the public library, the Virginia State Library. You were taking it passionately everywhere, and I was like, “This is incredible; you’re incredible.”

And so I visited the collection with you both, and I tried to get an appreciation for the depth of it. For me, trying to work on something like this, represents a lot of commitment so I wanted to be careful about what I committed to. Then once we got up there, there was just so much, and so many different ways to try to understand Louis Draper as a photographer. It was really fascinating. It’s still kind of mysterious to me, the ways in which he worked or how he perceived himself. Was he a working photographer? Was he an artist who was confined to being a working photographer some of the time? Was he aspirational?

I think he was; I think that Kamoinge is a good testament to that aspiration as they were trying to lift the recognition of African American photographers and artists. And he seemed to be culturally involved; he seemed like an intellectual, so I just needed to sort of unpack that a little bit. Ultimately we started bringing the work back to Richmond and trying to make some sense of it. Now working for a year and a half, we’re still only part of the way—I’m still only part of the way—I think Nell understands on a very elemental level what he was about. I’m trying to catch up.

![[Man with dog], c. 1950–90s [Man with dog], c. 1950–90s](images/candela_blog_sized/draper-0044.jpg) |

| Louis Draper [Man with dog], c. 1950–90s Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

SE: When you showed me the work, the images were so compelling and so strong and there was so much material. It’s such a huge project with a photographer to figure out what might be a working print versus a finished print, and then which of the finished prints with their different interpretations to choose. The printing process is such an important part, whether he’s emphasizing by lightening a certain area or darkening a certain area.

I knew what Gordon had done with Gita Lenz because we had also gone through the process—I’d reviewed a lot of her work, and was thinking about her as a female photographer in the 1950s and early ’60s who was very overlooked, and had been present and a part of a lot, but had been lost to history. I knew how well Gordon had organized that work, so that was the amazing thing for me, to have Gordon work with you and then organize the prints so that any image that I was interested in I could see: anywhere from “that was the only print,” to “there might be six, or ten.”

SE: I had to see all of the prints and choose from them, which made for difficult decisions, because sometimes it’s just an opinion, other times it’s clear that something is a working print, and that another is a finished print. It was an incredible privilege to get to then look through so much of Draper’s work and see so much of it. It’s an effort I hope to return to. I think it’s important for the museum to represent a sizeable body of his work because of his story in Richmond, but also to recognize the importance of what he was doing in New York.

![[Boy and H], c. 1950–90s [Boy and H], c. 1950–90s](images/candela_blog_sized/draper-0074.jpg) |

| Louis Draper [Boy and H], c. 1950–90s Gelatin silver print The Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust |

NDW: I appreciate everything that you have done. Gordon, Sarah, and Cheryl—

GS: Cheryl is an important person in this story, off camera, very important.

NDW: Yes she is, and I appreciate her. She’s very much into this collection. She’s just always, “Oh I called so-and-so or so-and-so emailed me, and we have appointments at such-and-such a thing.”

“Okay, all right,” I’d say, “so I’ll put that on my calendar.”

I remember when Cheryl attended my church and I met her for the first time. She had come from New Jersey I think; she had been to California, New York, and I think at that time she was living in New Jersey, and then she moved to Richmond. A friend and I were talking and I showed her a picture of Louis and an article—one of the newspapers here, Key Awareness, had an article of him and his picture. “Oh, this is her brother,” my friend said and handed the article to Cheryl who happened to have been sitting behind us. Cheryl said, “Oh, so-and-so and so-and-so, and Langston Hughes, he’s one of my favorites,” and so on. She looked at me and she said, “I do documentaries. I would like to speak with you after the service.”

And that’s how it got started. Just like that. She happened to be here. But Cheryl always says, “there are no accidents.” I think that it was meant to be. Of the whole church, she sat directly behind me. I had never seen Cheryl, and she had never seen me. This person that I was talking to just said, “This is her brother, so-and-so.” Just nonchalantly. And when Cheryl saw it, she said, “Whew,” and that’s how it started; that’s how it started. So, you know, I’m just grateful to God and to all of the people who have rallied around Louis’s work. I appreciate it all. ![]()

Contributor’s notes: Louis Draper

Contributor’s notes: Nell Draper-Winston

Contributor’s notes: Sarah Eckhardt

Contibutor’s notes: Gordon Stettinius