print preview

print previewback MATT DONOVAN

Almost a Full Year of Stone, Light, and Sky

He could see the white-washed rocks; the tower, stark and straight; he could see that it was barred

with black and white; he could see windows in it; he could even see washing spread on the rocks to

dry. So that was the Lighthouse, was it?

No, the other was also the Lighthouse. For nothing was simply one thing. The other Lighthouse was

true too. It was sometimes hardly to be seen across the bay. In the evening one looked up and saw

the eye opening and shutting and the light seemed to reach them in that airy sunny garden where they

sat.

—Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

If you’re gazing out over the Rome skyline on the Gianicolo hill, sipping a kiosk’s lukewarm six-euro beer, you’ll see it, there among the brick-tiled buildings and sky-jabbing cupolas and the city’s infinite shades of Tang, hunkered down with all the grace of an upturned cereal bowl.

Down the hill, there are two means of approaching it. You could weave in from one of the side streets to the north until you round some darkened bend and there it is, smack-dab across the Piazza della Rotonda in a ta-da, all-at-once splendor. Far better, though, is the slow reveal afforded by strolling in from the south. Step from the number eight tram, and meander through nameless side streets chockablock with scooters, tour groups, double parked trucks, palette stacks, purse shops, and prix fixe restaurants. Take your time. What you’ll see is only a beginning, a partial glimpse, a long curve slowly taking shape like an oversized, misplaced brick silo. Its familiar pillars and dome will be nowhere in sight. For as long as possible, allow what is known to be held at a distance even as it’s within reach.

|

Photo Courtesy of the Bern Digital Pantheon Project |

~

Pantheon, we say, hauled in from the Greek: pan, meaning all, and theios meaning of a god. More than anything else, this etymology is how we’ve come to agree–or wrongly guess—that this building was a place to worship all Roman gods during ancient times. Yet, like everything else we inhabit or inherit, neither its name nor function is that simple.

After its conversion to a Christian church in the seventh century, the building became officially known as Santa Maria ad Martyres. More informally, it’s called Santa Maria della Rotonda, whereas all of Rome’s brown historic-site signs direct visitors to “Il Pantheon.” Yet that name, even in ancient times, seems to have been more of an agreed-upon nickname. Dio Cassius, even though he was writing in the same century in which the building was constructed, finds himself scrambling to account for why it was known as the Pantheon. Perhaps it has to do with all the statues of the gods the building once housed, he writes, but ventures his own opinion too: perhaps it has to do with the fact that its vaulted roof resembles the heavens in which all of the gods reside.

In the end, no one knows its original name, nor how it might have been possible to worship all our myriad gods within one building, or if the building was ever in fact holy at all.

~

While its interior is comprised of seemingly endless architectural details to explore—trompe l’oeil niches, contrapuntal marble, the dome’s cement coffers high above—some have argued that its basic exterior structure is like that of a prototypical house. At one point, I remember looking at it from across the piazza dead-on, and at long last seeing what they meant: ignore the pillars and the dome’s visible sliver, and you have a square with a triangle on top.

This is how my son Cyrus drew his first home not long after learning to clutch a pencil, and, years later, this is more or less how he carved a house-like shape into his Etch A Sketch’s dark sand. But no matter if he’s using a Periwinkle Crayola or a nub of red chalk to inscribe his walls upon the walls of our home, his square capped by a triangle hat is mostly just a means of getting at the stories held within those shapes. He’ll finish his drawing, squint at its lines as if peering inside, then improvise tales about who lives there, who built it, what its pebble-bottom fish tanks and damp cellars are like. What he’s made is just a shell, a vessel, a starting point for riffing on whatever might transpire inside.

|

“Winter House” by Cyrus Donovan |

~

A few years back, I received a fellowship that allowed me to spend eleven months in Rome. It was a blissful time: relatively free of commitments, I spent whole days wandering the city and writing about whatever caught my eye. There was no plan beyond hunting down some sought-after thing—a painting, a fountain, a particular trattoria’s mozzarella-oozing zucchini blossoms, some Bernini wind-whipped marble furl. I could stumble across a guidebook reference to a rarely seen Last Judgment fresco, for instance, and by midmorning the following day, spill from an elevator into a church’s choir loft and find myself standing before its radiant slew of haloed apostles and angels. Back at my desk, I might jot notes about wings like fountains of flames, or perhaps instead tackle the surly mustached nun who had chaperoned my fresco pilgrimage and flicked the room’s lights on and off after I’d lingered too long.

“No one suspects the days to be gods,” Emerson wrote, but for the short window of that time in Rome, I had faith in little else. The city was inexhaustible, and some of those days, by god, revealed themselves to be unfathomable, awe-crammed things. No matter what I pursued, seized, flitted past, devoured, or stood stupefied before, there was always a wonder-packed still-more to pounce upon the next day.

Gradually, though, the Pantheon became an exception to all of this wafting. I began to reroute my roaming so that, no matter my far-flung agenda, I’d be able to walk once more beneath its dome. As my time in the city neared its end, I found myself forgoing the chance to visit another work of art or new-to-me ruin so that I’d be able to carve out whole afternoons—or even five minutes—to sit in that building’s bustling cool, to glimpse where its light happened to fall, to check if its revealed patch of sky happened to be cloud-pocked or spotless blue.

“What is this quest all about?” a friend finally asked me, yet in all of my repeat visits to the building, I never had much of a defined pursuit. For better or worse, my compulsive returns were something more akin to Philip Larkin’s “Church Going,” in which the narrator stops by churches just to poke around, never quite sure what he’s seeking. It’s a dabbling fueled by a loss of faith, although he never locates an alternative to belief. Instead of doctrine, there’s the hum of desire and an ill-defined tethering. There’s the lure itself and the way “someone will forever be surprising /A hunger in himself to be more serious, / And gravitating with it to this ground.”

I must admit that I was surprised by my accruing hunger for the Pantheon and how my own lurching compass settled there. After months of searching out churches in Rome—the city boasts over nine hundred—why did this one structure trump all others? After visiting ruin upon ruin, what did this one ancient place—not a ruin against all odds—offer, suggest, redeem?

~

And what facts do we need, how far back must we go, to comprehend the Pantheon’s particular light? Even if mostly I’m content to simply experience the span of its dome and the sun’s flare on its stone, it’s still worth remembering why the building sits on that particular there.

Some say you need to cast a gaze all the way back to Romulus, the fratricidal co-founder of Rome. The Pantheon stands, it’s believed, on the exact spot where he either ascended into heaven on a golden chariot like a slingshot-fired jewel or he was ambushed along the marsh’s edges by a gang of knife-wielding senators who hacked his body to pieces, then scattered them in the lake.

And some say you need to know how Julius Caesar wanted to give thanks to Mars after winning four wars, which really meant needing to appease his soldiers with extravagant parades as well as distract the public from all those years he sucked the coffers dry. Thus elephants, chariots, prisoners of war, drunk officers bellowing victory songs, and war booty lugged past cheering crowds that held aloft drawings of Cato tearing at his own wound. Thus Veni, Vidi, Vici and five days of beast fights and the first-ever staged hunts for giraffe. Thus gladiatorial battles with tridents, wooden shields, axes and nets, followed by armies of hundreds of men spearing and slashing, because this is what the crowd wanted to see. Or so they thought, until the spectacle was upped a notch with naval battles in a basin built near one of the Tiber’s bends where ships carrying thousands of men—some serving as proxy gallant Romans, some relegated to Tyrian scum—rammed and stormed and bludgeoned each other with oars.

Years after slaves filled in the basin where those mock battleships had sailed, Emperor Agrippa, in a bold claim about legacy and honor, choose this exact location to build a temple to the God of War. That temple burned down – we know little about it – and later was constructed again before burning down once more before Hadrian, in turn, chose that same spot for his dome to end all domes.

Thus the light we gather to see.

~

When the building’s dome was first constructed, its interior was painted azure and each ribbed coffer had anchored in its center an enormous bronze rosette. Perhaps this is what Shelley was referencing when, in one of his many letters sent from Rome, he described the Pantheon as “the visible image of our universe.”

Many believe the dome was intended to represent the heavens: those rows of twenty-eight recessing trapezoidal coffers signifying the Roman twenty-eight day lunar cycle; the painted blue, of course, representing the sky; and the rosettes serving as the gleaming pinpricks of scattershot stars. Many, too, have noted the importance of the number sixteen within the building (sixteen granite pillars support the portico, while eight apses combined with eight exedras encircle the building’s interior), inviting speculation that the building references Etruscan cosmology in which the heavens are separated into sixteen different dwelling spaces for the gods.

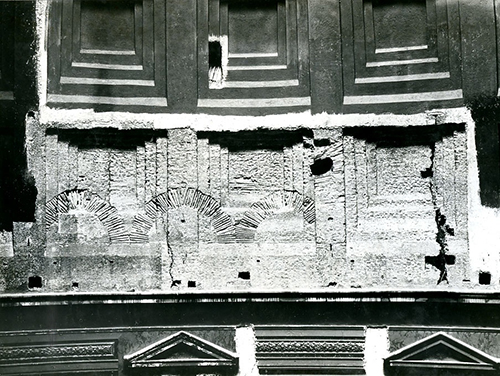

|

Photo Courtesy of the Bern Digital Pantheon Project |

When I first heard about this ancient division of the skies, I imagined each god hunkered down and unable to leave their prescribed territory, abiding by rules not that dissimilar from my hometown’s Pee Wee Soccer games, when we were forced to stay put in our assigned painted grid on the field, waiting for the ball by chance to roll past or else face the shrill-whistle wrath of a hyper-vigilant dad referee. But despite the pretense of those designated spaces, the Etruscans knew both their gods and our world too well to claim that any one portion of the sky could house a single name. Forget row after row of suburban cul-de-sac cookie-cutter homes; forget any straight-edged, tic-tac-toe-like grid segregating Xs from Os. In their theory of the heavens, Jupiter shares a plot of sky with both Good Health and Nocturnus, God of Night. The God of War rooms with the God of Freshwater, and Wisdom resides with Discord. Fortune bunks with a wide range of crammed-in Shades, and, out in the cosmos further still, rogue deities called the Zoneless dwell, bound by nothing at all.

Even if Shelley knew nothing of the Etruscan’s scrambled-up world of the divine, by the time he strolled through the Pantheon’s doors, the dome’s blue paint had long since crumbled, and each of those rosettes’ star-blaze stands-ins had been hacked off and filched many Rome-raids back, leaving those stair-step coffers to serve as frames of just cracked cement. The visible image of our universe? Shelley’s description might have been intended as shorthand for limitless skylark-esque soaring, but the proxy cosmos he actually saw would have been age-pocked and scabbed with decay and long since hacked for its metal.

|

Photo Courtesy of Fototeca Unione, American Academy in Rome |

~

Last night, a dream: somewhere on the snow-covered streets of Boston, I had misplaced my son. One moment, he held my hand, and the next, his palm had slipped my grip and my whole body was honed to howling his name into a January wind that whipped the drifts higher still.

I woke, sweaty and rattled, but as the day inched forward, I found myself thinking about what an anomaly the dream had seemed. In my own day-to-day life—from the classes I teach, to the night skies I scan—I rarely know what I’m looking for. I wondered: how much do I want certainty in what I seek? Do I crave more answers, facts, and faith or, alternatively, how much of my own meandering, leapfrogging, scuttling from and to if,gives me exactly what I need?

Despite the fact that the Pantheon was converted to a Christian space long ago (and despite the crosses you’ll find there), the building, I’ve come to believe, doesn’t abide by any one creed. Unlike, say, the way a gothic spire suggests finger-pointing toward a god residing above as sure as stone, the Pantheon doesn’t insist but rather reveals. Especially since we've been relegated to guesswork regarding the building’s original purpose, it has become, by beautiful default, a kind of temple of speculation, of wonder and thus not-knowing now and forevermore.

Here’s an empty niche, a bit of light, some sky. What does it mean, what will you do with it, how will you respond?

~

Stendhal, apparently, viewed the Pantheon as a kind of aesthetic litmus test, judging its visitors based on their level of ravishment when exposed to its light and scale. I think I understand.

There are days when that building seems as unlikely and fantastical as anything plucked from the stuff of legend: to enter its space and not go slack-jawed would be as if you had stepped over the threshold of the Tower of Babel and responded with a shrug. Some days, yes, upon entering the Pantheon, the world narrowed to that single spot, and I felt as if I were seeing sky and light for the first time. I would be gobsmacked by that impossible dome, or merely at the thought of how many others, through nearly two millennium, had stood there as well, craning back their heads, feeling gobsmacked too.

But, then again, there were times during my stay in Rome when I would find myself in the Pantheon while in the midst of running errands, on my way to catch the number forty-four bus, plastic sacks sagging with the weight of cantaloupe and coffee and cans of soup, and there, jam-packed among the tourists holding up iPads to the streaming-in light, I might feel as much rapture for that ancient space as I did for the squeak of wet sneakers across its floor.

Along those lines, although I will never doubt my son Cyrus’ capacity for wonder, he could seem equally jazzed by the tower of whipped cream heaped upon his lemon granita as he was about watching light sear through that oculus. The first time he walked into the Pantheon, I watched him glance at the dome for a moment, then turn his attention to trying to decode the graphics on a sign that declared the building’s prohibitions.

No tank tops, no food, no phones. Watch for pickpockets. No loud noises. No lying down.

~

Here is the way that Byron describes the building in its brief cameo within the 16,000 lines of his poem Don Juan: “Simple, erect, severe, austere, sublime.”

While I suppose that all of his adjectives are correct, in what way do any of those abstractions help to depict the Pantheon? Anachronism aside, they just as easily could be describing the Eiffel Tower or, for that matter, one of the tarred railroad bridges straddling arroyo sand just a few miles from my home. Byron’s brief descriptive litany, stripped of context (and, admitted, also perhaps stripped of “erect”), seems closer to the voice-over from an SUV advertisement than to language intended to capture the Pantheon’s multicolored, variegated Christian-inscribed-upon-pagan marble-mash-up of the building’s lower half.

At the same time, I understand the need to latch to any ballpark word. I’m no more surprised that Byron took this broad-stroke route than my son turned to decoding the building’s rules. The Pantheon’s enigmatic immensity, like all immensities, encourages whatever foothold might be found.

Sublime, severe. No gum, no smoking, no dogs.

~

Byron’s stately procession of modifiers underscores not only the complications of trying to describe the place, but, moreover, the way in which language has always seemed to be at odds with the structure. Words, it seems, not only fall short, but also obfuscate our understanding.

Looking at the Pantheon from across the Piazza della Rotonda, it’s hard to miss its famous inscription, engraved on the portico in large Roman type: M. AGRIPPA. L . F. COS. TERTIVM. FECIT. Despite the bold bronze lettering, the meaning is not much more than an ostentatious tag: “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, made this building in his third consulate.” For nearly two centuries, we had no reason to doubt the inscription’s claim, and without fail the building was referred to as Agrippa’s Pantheon. The words, however, are a lie.

In the mid-eighteenth century, bricks were excavated from various spots inside. Each one bore a brick maker stamp that, through references to supply yards and names of specific supervisors, placed its construction between the years 118 and 126 AD and revealed that the Pantheon had been built by the Emperor Hadrian. Like that, a single fact that we thought we knew was swatted away.

My son chatters out a story about his drawing’s invisible jet-powered camel that’s tethered out of sight in the backyard of his triangle-perched-upon-a-square house. Meanwhile, we’ve also slipped from the given to imaginative speculation: after centuries of studying the Pantheon, our stories have shifted from the feat of Agrippa’s freestanding dome to why Hadrian pretended the building wasn’t his.

~

So what happens when you stand inside the Pantheon?

The earth turns, which, depending on the time of day, makes the light appear to either rise or drop.

Light slowly cruises coffers, marble, and pillars, highlighting whatever falls beneath its path. Three bronze crosses, dust bunnies on a ledge, this particular scrap of ceiling, the man at the audio guide booth picking at his ear, now just the corn-yellow backdrop in the lower left edge of that annunciation scene—as if saying notice this, so much depends. As if beyond illuminating this skated-across mishmash of things, there was nothing more to say.

|

Pantheon, light on attic zone / Photo by Tobias Kirchway |

By midday in summer, it blazes on the floor, gliding over those patterned circles and squares. Some of us skirt its edge, as if we couldn’t bear being caught in the glare. Some of us let the light hit us dead on, and we stretch out our arms or strip off our socks, waggling our toes on the sun-warmed floor, hamming it up for photos before slipping from that blaring heat into the shadow’s prescribed cool.

Come back in a few hours and the sun’s beam will be rising again. Stay long enough and—this is perhaps what we’ve pilgrimaged for—the light will change as it climbs. It turns from a nearly perfect circle shape to a crumpled disc warping across the coffers. As it lifts toward the oculus, as each day it must, the disc becomes a cropped mountain peak, a chewed crust of bread, a deep-hulled ship without a sail. Now a sliver of moon, now an oblong shape inching upward for which we have no words.

|

Photo by author |

Just as the last bit of daylight hovers at the rim, giving us a glimpse of a single cobweb strand—slung diagonal across the oculus, framed by a backdrop disc of sky, lifting in a breeze skimming past—we’re told we must leave. A man with a lanyard looped around his neck grips the sides of the same pulpit used by the priests and solemnly intones into the microphone a sermon that goes something like this: The building is closing. Walk toward the exit. Thank you. Please leave.

In many languages, again and again, he tells us to go forth into the wide world. Other lanyard-bearing men and women spread their arms wide, fan out across the marble floor, and, striding toward us, make precise little flicks of the wrist, shooing us toward the exit.

In a few swift moments, the building is empty except for the guards who swing the bronze doors shut and then we’re all outside although we remain beneath the exact same light and—this is the part that’s easy to forget—a wider span of the same sky. We’re stepping across the piazza’s bricks, past the gladiators with their plastic swords trying to shake us down for ten Euro snapshots, past the horse carriages and taxis and necking Parisians and the legless woman on a wheeled-about cart who rattles coins in her plastic cup. Past Rome tour hawkers and past two men making a shrill melody from The Nutcracker by rubbing wineglass rims, past gangs of pigeons and gangs of guys selling splatable, water-filled pigs (“Hello. Look please! For the kids.”) as our earth still turns and we seek out some just-blocks-away little hole in the wall place known for its hunks of fried cod and anchovy-heaped buttered bread. ![]()

![]()

[“Almost a Full Year of Stone, Light, and Sky” is excerpted from a longer essay, which will appear in A Cloud of Unusual Size and Shape by Matt Donovan, forthcoming from Trinity University Press in May 2016.]