print preview

print previewback CAITLIN DOYLE

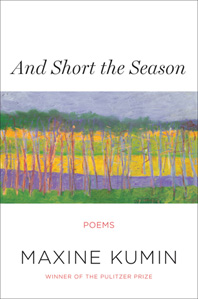

Review | And Short the Season, by Maxine Kumin

W. W. Norton & Company, 2014

|

“Saving is a form of worship,” Maxine Kumin writes in “The Path, The Chair,” a poem from her most recent and final collection And Short the Season. The line calls to mind one of her much earlier pieces, “The Pawnbroker,” in which she describes her childhood as the daughter of a father who owned a pawn shop: “Everything good in my life was secondhand.” Neither poem presents an entirely happy view of what it means to preserve the past; the words “worship” and “good” take on ambiguous nuances among the images and sounds that surround them. Published after her death at age eighty-eight last February, And Short the Season invites us to engage the tension between salvage and loss not just in her individual poems but also in the bigger context of her life’s work. What are the aspects of Kumin’s final book, and her oeuvre at large, that will persist, like the regenerating farmland of “The Path, The Chair,” in readers’ minds?

Themes of preservation and endurance reverberate through And Short the Season in poems about farm life, Kumin’s girlhood as “the only Jewish child at the Convent / of the Sisters of St. Joseph,” personal relationships, and politically charged issues like war and torture. Just as Kumin grew up living between very different poles, she forged a literary path that placed her between varying points of definition. As Hilda Raz has noted, she occupied an unusual position as “a Jewish woman writer who claims the natural and literary landscape of her Puritan fathers.” Her lauded skill with rhyme, meter, and traditional forms, along with her farm-centered subject matter, earned her the nickname “Roberta Frost,” yet reviewers have emphasized the differences between the two poets as often as their similarities. The poetic structures in And Short the Season range as widely as the subject matter, from strictly formal pieces to poems that employ form in a looser way (rough meters and slant-rhymes abound) to free-verse pieces. In And Short the Season, as in Kumin’s earlier books, we encounter a poet whose “central brilliance,” Neal Bowers has written, is her “refusal to be boxed and labeled.”

Most of the acclaim surrounding Kumin’s work has focused on her strengths as a poet of nature and individual experience, while the majority of criticism regarding Kumin’s poetry has centered on weaknesses in her engagement with political subject matter. Many of the poems in And Short the Season reaffirm these past assessments of her work. Yet we also find powerful examples of a type of Kumin poem that has not yet had its full critical due. A close look at “National Velvet,” one of the most striking pieces in the book, calls our attention to the fact that, if Kumin falters sometimes in the political realm, she has often forged memorable poetry from another aspect of public life: popular culture, both high and low.

In “National Velvet,” Kumin explores the mythos and reality surrounding Hollywood icon Elizabeth Taylor. She employs a breathless syntax and forward-driving internal rhymes to capture both the restive passion of Taylor’s adult years and the innocent abandon of her star-making performance as a child in the hit movie National Velvet:

When the Vatican charged Elizabeth Taylor

with erotic vagrancy in 1962 for sleeping

with Richard Burton while still married to

I forget who, there were so many, all

I could think of was her soaring over fences

on The Pie, her first love, a piebald horse

with one blue eye who’d leapt a five-foot

stone wall to get into another pasture . . .

Kumin then invites us to see a parallel between the piebald horse with the patches and mismatched eyes, “two / traits suggesting some erotic vagrancy— / a hybrid rogue slipped generations back / into the registry,” and Taylor herself. The poem prompts us to wonder whether Taylor was always the person she would become, born that way like the piebald with its heritable traits, or if her identity took shape as the result of public pressures. After all, the young Taylor that Kumin so fondly recalls jumping fences on horseback was a child actress performing a role written and directed by others. By the end of the piece, Kumin achieves a complexity common to her most resonant poems about elements of popular culture:

. . . Liz married seven men,

Burton twice, by which time he was losing

his hair and she was growing a double chin,

but let us remember how fiercely she flew

over fences on the wild piebald horse

with one brown eye and one that was blue.

In these final lines, we hear a mixture of tongue-in-cheek irony, nostalgia, and wistful amusement. We also perceive, by the poem’s finish, that the speaker’s sense of connection to Taylor is real, and thus the piece resists placing itself either apart from or above the pop cultural influences that surround us. Kumin moves from subtle slant rhymes (“men” and “chin,” etc) to a pair of perfect end-rhymes—“flew” and “blue”—that chime loudly at the poem’s finish and tease us with a kind of false closure. This effect underscores the speaker’s willingness to embrace the artificial aspects of Taylor’s public persona as part of her, paradoxically, genuine appeal.

“Xanthopsia,” another of the most striking poems in And Short The Season, focuses on a figure at the loftier levels of the cultural spectrum—Vincent Van Gogh. Through her examination of Van Gogh’s use of yellow paint, explored in relation to the actual events of his life, Kumin again probes the tension between artifice and reality in both the forging of identity and the creation of art. The poem ends with these lines: “ . . . Science has a word— / xanthopsia—for when objects appear / more yellow than they really are but who’s / to say? As yellow as they are, they are.” Kumin’s repetition of “they are” echoes “National Velvet” in its suggestion that we can’t fully resist the ways that crafted worlds can compel us as much as, and sometimes more than, actual realities.

Though poems that engage popular culture comprise a small part of Kumin’s body of work, the strength of “National Velvet” and “Xanthopsia” prompts us to recall that some of the most outstanding poetry in Kumin’s earlier books has also centered on pop cultural elements. Examples include “Casablanca” (from Halfway), which examines the complicated relationship between cinema and reality, and “A Game of Monopoly in Chavannes” (from Nurture), a poem that explores familial connections through the lens of the iconic American board game. In “Casablanca,” reflecting on the movie of the same name, Kumin describes a boy she once knew who “could do the dialogue all blurry.” When the boy ends up dying in a World War II destroyer, “swallowed in the other half of that real war,” Kumin invites us to see just how “blurry” the line between popular culture and reality can become. As the movie ends and we “come back to where we really are,” Kumin makes clear that “where we really are” is simultaneously within and outside of the fantasy world of cinema. Many of her poems about pop-culture subjects suggest that, like the young man who does the dialogue from Casablanca, we imitate the roles available to us and ultimately find that our own realities echo those roles in surprising ways.

If aspects of And Short the Season invite attention to Kumin’s little-discussed acuity as a poet of popular culture, other poems in the book reinforce the critical responses surrounding her engagement with political subject matter. In her New York Times review of Kumin’s collection The Long Marriage, Megan Harlan observed that, while Kumin’s “tonal clarity is transformative” in her most compelling poems, her pieces that approach political matters and social issues can at times “rely too heavily on description, rather than delving for deeper innovations.” In And Short the Season, readers again encounter the fact that one of Kumin’s most defining stylistic qualities can either vault her work into memorability or flatten it: the very accessibility that she so successfully employs to deepen the complications of her more personal work can lead to a one-dimensional effect when she steps into the political realm.

In “The Luxury,” one of the politically engaged poems that appears in And Short The Season, Kumin explores the “luxury / of not knowing” the full suffering of animals and people in less privileged circumstances, specifically the dogs and children that live in a neighboring house:

I have the luxury

of not knowing when they were last fed

or of not seeing where the five children

sleep or what covers them or how their father

serving a year in the House of Correction

for petty larceny and public drunkenness

is being corrected. All of us neighbors

who have fought with the town for years

to take action have the luxury.

Kumin’s directness prompts us to look for more nuanced developments, in both language and content, as the piece progresses. When the poem moves to describing an ineffective judge who has failed to help the needy family, we sense that an additional layer of complexity might enter the poem. Instead, Kumin ends on the assertion that “He too has the luxury of unknowing.” Critic Jan Schreiber has argued that Kumin’s political poems, rather than offering “illumination,” can sometimes fail to act as more than “a hand on the lapel shaking us and saying: ‘Look isn’t this awful, isn’t this sad?’” When Kumin shakes our lapels in “The Luxury,” as in some of the book’s other politically charged poems, we agree that what she shows us is sad. But we find ourselves wanting to experience more than just a sense of agreement with the poet’s social values.

In And Short the Season, as in her previous books, most of the poems that ultimately do more than shake our lapels confirm Kumin’s reputation as a poet whose “primary loyalties,” as Richard Tillinghast has observed, are to “personal narrative” and the “natural world.” The poem “Either Or,” which appeared in the 2012 edition of The Best American Poetry, stands out in And Short the Season as evidence of what Kumin can accomplish, at her best, through her exploration of nature and the self in relation to each other. Here is “Either Or” quoted in full:

Death, in the orderly procession

of random events on this gradually

expiring planet crooked in a negligiblearm of a minor galaxy adrift among

millions of others bursting apart in

the amnion of space, will, said Socratesbe either a dreamless slumber without end

or a migration of the soul from one place

to another, like the shadow of smoke risingfrom the backroom woodstove that climbs

the trunk of the ash tree outside

my window and now that the sun is updown come two red squirrels and a nuthatch.

Later we are promised snow.

So much for death today and long ago.

Kumin deftly intersperses Socrates’ words in a poem whose structure embodies the irony in the phrase “the orderly procession / of random events.” The three-line stanzas give the piece a feeling of order, while the pressures of randomness and chaos find expression in the poem’s winding syntax, the sometimes jarring enjambments, and the lack of periods until the final stanza. Through the ambiguities embodied in the first four stanzas, Kumin earns the assertive closure of the poem’s final couplet with its perfect rhyme. Of course, it’s essentially just a sonic closure, a gesture toward certainty and comfort, because both the poet and the reader know that the eclipsing of death by the immediacies of life (sun, birds, snow)—“so much for death”—cannot be the final word for any of us.

In “Either Or,” Kumin showcases some of her most characteristic and noteworthy strengths as a poet. The piece demonstrates her facility for mixing different levels of diction, as in the colloquial “so much for” sharing a line with the more formal and antiquated phrasing of “long ago,” her adeptness at evoking fruitful double meanings with her word choices (which she does through “crooked” and “will”), and her skill at merging the largess of the universe with the common elements of everyday life. Above all, “Either Or” embodies the gift that has always seemed central to Kumin’s strongest work: her ability to forge poems that reach just enough toward order, symmetry, and unity to heighten our awareness of mysteries that pull against the desire for control and comprehension.

In addition to “Either Or,” “National Velvet,” and “Xanthopsia,” And Short the Season presents readers with several more pieces that will likely enter the realm of Kumin’s most beloved work, along with popular poems like “Woodchucks,” “Homecoming,” “The Long Approach,” and “Sleeping with Animals” from Kumin’s previous collections. Other particularly noteworthy pieces in the book include “Purim and the Beetles of Our Lady,” a complex meditation on language, politics, and nature, and “Seeing Things” and “Ancient History in the Eye Center,” two poems that explore the vision problems with which Kumin struggled in her later years. In “Seeing Things,” when Kumin asks the doctor about her “visual / hallucinations”—“the product of a mentally / healthy brain that is filling in the blanks” in her sight—his response haunts us: “They will always be with you, he said. Try to befriend them.”

Throughout her body of work, Kumin invites readers to reflect on those aspects of life that will always be with us, as persistent as the hallucinations in “Seeing Things,” Van Gogh’s yellow paint in “Xanthopsia,” and the cinematic worlds in “Casablanca” and “National Velvet.” She leads us to discover again and again that the elements of experience that most persist in our memories are those that take shape—like her poems themselves—from a combination of compelling artifice and raw reality. If “saving is a form of worship,” as she asserts in And Short the Season, then Kumin’s final book reaffirms her legacy as a poet who shows us that what we save, whether real, forged by imagination, or some combination of both, becomes who we are. ![]()

![]()

Maxine Kumin (1925–2014) published several books of poetry during her life, including And Short the Season (2014), Where I Live: New & Selected Poems, 1990–2010 (2010), Still to Mow (2009), and Bringing Together: Uncollected Early Poems, 1958–1988 (2003), all from W. W. Norton & Company. She also authored Up Country: Poems of New England (Harper & Row, 1972), for which she received the Pulitzer Prize. Along with books of poetry, she is the author of a memoir, Inside the Halo and Beyond: The Anatomy of a Recovery (W. W. Norton, 2000); five novels; a collection of short stories; more than twenty children’s books; and five books of essays, most recently The Roots of Things: Essays (Northwestern University Press, 2010). Kumin has been the recipient of the Aiken Taylor Award in Modern American Poetry, an American Academy of Arts and Letters award, the Sarah Josepha Hale Award, the Levinson Prize, a National Endowment for the Arts grant, the Eunice Tietjens Memorial Prize from Poetry magazine, and fellowships from the Academy of American Poets and the National Council on the Arts. She earned an MA and a BA from Radcliffe College, and she has served as the Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress and Poet Laureate of New Hampshire, and she is a former Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.