An Evolution

Commentary by Howard Risatti

|

|

| Kiyomi Iwata From Volume to Line Visual Arts Center of Richmond |

|

Kiyomi Iwata, a Japanese American whose artistic career began in Richmond in the late 1960s, has, over the years, created a major body of work that reflects the artistic traditions of Japan as well as an engagement with contemporary American art. The length of her career certainly deserves mention—sustaining the quality of one’s artistic output over many years and not becoming a parody of oneself is no easy matter. Also of note is the fact that her primary inspiration has repeatedly come from fiber, a distinctly craft material. That she was raised in Japan where traditional crafts are still held in high regard probably accounts for this. Here in the United States where the situation is somewhat different, that she has managed to elevate fiber to the level of high art based on a sensibility derived from traditional craft is clearly unusual and may represent a challenge to some attitudes about what constitutes art, contemporary or otherwise. However, whether or not she works in a craft material doesn’t really matter. What does matter is the quality of the work and how it encourages the patient and attentive viewer to engage in an intimate dialogue with the work.

Her work can be roughly divided into two strains that develop more or less in tandem—those showing direct influence from traditional Japanese art and those reflecting inspiration from contemporary American art. Among the former is a series based on the Japanese furoshiki, a cloth traditionally used to wrap or bundle clothes, groceries, and sometimes even gifts.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Auric Fold with Tanka Seven, 2015 aluminum mesh, gold leaf, embroidery thread 17 x 17.5 x 9 in. |

In 1991 while Iwata was a resident at Yaddo, an artist colony in Saratoga Springs, New York, she began exploring the idea of furoshiki cloth to create her own version of such bundles. Referring to them as “folds” but thinking of them as containers, she experimented with various types of metal mesh, including bronze, copper, and stainless steel, but eventually settled on aluminum because it is easily manipulated, holds its shape, and is readily available. By carefully folding the mesh, always embellished with silk edges, French embroidery knots, and precious metal leaf such as gold (auric), bronze, silver, or copper (cupric), she transformed this traditional practice into a unique form of high art. In doing so, she realized the special quality that metal and textile have when put together, not unlike traditional Japanese armor made of metal and silk.

Examples from the “Fold Series” include Auric Fold With Tanka Six (2014) (19 x 21.5 x 6.5 in.) and Gray Orchid Fold Three (1995) (15 x 20 x 13 in.), both intended to be placed on a wall despite being quite large. Furthermore, while they are rather sculptural in form, tied with an elegant knot, they still exhibit a sense of weightlessness as a result of the delicacy and transparency of their materials. It is almost as if they are enfolding space, bundling it, as it were. Their interiors are either empty voids or contain a tanka—a short Japanese poem of thirty-one syllables in five lines. Auric Fold with Tanka Six contains such a tanka that is visible inside the work but not readable. According to the artist, the intent is to suggest a container of mysteries or secrets. The effect, because of its beauty, something achieved through the elegance of its materials and the special care with which it is made, elevates the object and brings to the fore the act of giving rather than receiving. In a sense, works in the “Fold Series” become reminders, metaphors if you like, for human generosity and even remembrance; they are like gifts for the spirit.

Iwata lived near New York City in 2001, and the events of 9/11 had a profound impact on her; as she put it, “Our way of life changed permanently.” In response, she began making a new series of two-dimensional hanging tapestries reminiscent of traditional Japanese hanging scrolls. Like the “Fold Series,” they too are made of metal mesh embellished with gold leaf, stitching, and French embroidery knots, which look like small beads attached to the surface of the mesh. Because the gold leaf is applied in squares creating a kind of grid on the surface, she refers to the series as “Auric Grid Hangings.” She also copied in gold lettering tankas or other eighteenth-century Japanese poems such as haiku or waka onto the hangings. Even though these short poems are translated into English, they are difficult to read because they are written in gold on gold. Later, so as to make them even less specific, less legible, she copied them in Japanese script, something seen in Auric Grid Hanging With Tanka Four (2002). In Auric Grid Hanging With Tanka Nine (2002), a slightly different version, the untranslated poem in Japanese characters is written in gold directly onto the metal mesh.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Auric Grid Hanging with Tanka Nine, 2015 brass mesh, aluminum mesh, gold leaf 64 x 18 x 10 in. |

Because the mesh is transparent and hangs in loose folds in front of the gold-leaf background grid, Iwata creates a delicate three-dimensional double scroll. In other variations from the series, the words are also broken apart and partially obscured. Iwata’s intention is to encourage viewers to “create their own interpretations, holding within themselves their own thoughts—[thereby creating] another container of unknowns.”

In 1985, before the creation of these two series, Iwata made a work out of dyed silk organza, a very sheer, crisp fabric that is strong and durable. She titled the piece Red Box, and it marked the beginning of a series of silk organza boxes. As the series evolved, she added wire stitching to help the boxes keep their shapes. She also had what she described as a major breakthrough when she hit upon the idea of tying the sides together by knotting twisted fringes of the silk fabric rather than by using needle and thread to sew them. Red Box was soon followed by others in various colors such as Pink and Silver Box (1988) and Orange Box (1987). At 8 inches square, they are small, delicate objects obviously intended to be viewed up close and in the round on pedestals to create an intimate and personal experience for viewers.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Pink and Silver Box, 1988 silk organza, dye, silver leaf, silk thread 8 x 8 x 8 in. |

In 1988, Iwata was accepted into the 13th Lausanne Biennale in Lausanne, Switzerland. At the time, many fiber artists who had been showing in the Biennale were making large, monumental tapestries. This prompted her to increase the size of her work as well. She did so, not necessarily by making bigger boxes, but by carefully arranging her boxes on the wall in vertical rows or in grids, using an ingenious system of clear plastic backs and Velcro. Untitled (1987), the work she made specifically for the Lausanne Biennale, contains forty-nine red boxes of dyed silk organza arranged in a grid of seven boxes by seven boxes; the result is a sculptural grid that is 7 x 7 ft. x 10 in. This practice continued even afterward; later arrangements are also quite large but often even lighter and more colorful. Indigo Grid (2011) contains twenty boxes that shift from solid color at the bottom to a checkerboard pattern at the top, while Water, Earth, and Sky Two (2001) contains twenty-five boxes of translucent cream-colored silk organza embellished with irregular patches of gold leaf. And one of the largest, Cadence Eight (2008), contains fifty boxes arranged on the wall in a grid.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Indigo Grid, 2011 silk organza, indigo dye, stiffener, metal wire, 39 x 32 x 5 in. |

Most probably in response to these works, the critical literature on Iwata makes reference to Minimalist sculptors like Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Tony Smith, Larry Bell, and Carl Andre, and post-minimalist process artist Eva Hesse—an important group, to be sure. One presumes this reference arises because Iwata’s boxes and grid installations are reminiscent of the repeated boxlike forms typical of Minimalism, while her use of cloth and thread echoes Hesse’s multiples made of wrapped thread, wire, and stiffened cloth multiples—all obvious connections to Iwata’s work. The differences, however, are enormous. Minimalism’s focus on preconceived, pristine forms that look machine-made reflect American industrial culture. Their techniques emulated factories, assembly lines, and Modern design, making use of modular units that they stacked, hung in rows on the wall, or arranged in rows on a gallery floor.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Water, Earth & Sky Two, 2002 silk organza, stiffener, gold leaf, metal wire 35 x 36 x 6 in. |

To see Iwata’s work as somehow in sympathy with such work is to miss its very essence, for she operates from a totally different sensibility. Yes, she does make boxlike forms and hangs them in grids, but she rejects the neutral, nondescript colors of Minimalism—no flat white or dull grey-black for her. And though she uses metal mesh and metal leaf, she also favors organic materials like silk organza rather than hard steel and plastic. It seems that Iwata dislikes the pristine, hard surfaces of metal and plastic; they appear cold to the eye, and in the way they reflect light, they seem to repel the hand and discourage touch. To Iwata, it seems, there is no poetry in such forms because they don’t encourage the viewer to visually embrace the work. What she seeks instead is a sense of intimacy, not the feeling of an otherworldly realm beyond the human. This is evident in her use of silk and in titles that often refer to natural elements, such as water, earth, and sky. It is also evident in her colors, which are rich and vibrant, often shimmering with gold leaf that creates a translucent light that penetrates deep into the core of her forms. The boxlike shapes in her series are never identical, modular units in the mode of industrial production; rather, they are individually made pieces that appear so delicate and oftentimes so lumpy and misshapen that they almost seem to wobble, to be on the verge of collapsing before the viewer’s eyes. That’s why even her tall grid installations seem benign rather than imposing or menacing. If they collapsed, it would be less like an avalanche than a shower of organza silk.

In other words, her choice of material reflects a concern for the way her works interact with viewers. Even when her pieces are large, her elements are small and delicate so as not to psychologically dominate the viewer or the actual physical space of the gallery. Similarly, with her non-wall pieces, she avoids making person-sized cubes that are so big that they must be placed on the floor and thus become obstacles that literally and metaphorically challenge the viewer by standing in his or her path. Instead, Iwata makes objects that rest on pedestals and, at times, opens them so as to create container-like forms that comfortably fit the hand and encourage a sense of touch, thereby subtly engaging both the human body and psyche.

This same attitude is apparent in works from her “Aperture” series, which evolved from the “Box” series. In her “Aperture” series, it is as if her boxes became wider and taller. Even though they are stiffened with liquid plastic to make them stable, as in Aperture No. 2 (2005), they look so precarious as to hardly pose a barrier to the viewer, due to the way their bases are shaped and embellished with gold leaf or surrounded with gravel on low pedestals. In fact, the effect is such that viewers must tread carefully lest they upset the object.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Peach Three, 2003 silk organza, stiffener 20 x 14 x 9 in. |

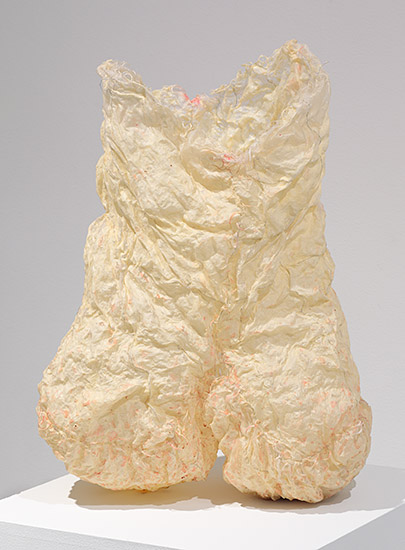

While working on the “Auric Grid Hangings” in 2003, Iwata received a commission from one of her collectors for a new work to be made of silk organza, a material she hadn’t used for some time. Fulfilling the commission led her back to working in silk organza, but this time, instead of making boxes, she began making works in the shape of the human torso. As already noted, the work of Post-Minimalist Process artist Eva Hesse has been mentioned in relation to Iwata’s work. The apparent connection is probably because of these torso pieces. Like her previous work in silk organza, these too are stiffened with liquid plastic so as to make them freestanding objects. But unlike Hesse’s works, whose surfaces often suggest flayed skin or some kind of psychological trauma, the works in Iwata’s “Torso Series” are translucent forms essentially without mass, so they tend to be lighter, more benign, and more container-like than mutilated body. Like Peach Three (2003), they are placed on medium-sized pedestals so that viewers encounter them torso-to-torso as if approaching another person. In this way, they evoke an uncanny sense of both a human presence and human absence; it is if someone has just walked out of their skin and left behind a mold of their body.

Sometime in 2009, an acquaintance gave Iwata some unusual silk thread called kibiso. A silk worm usually spins about 3,000 meters of thread during its lifetime. It is the first ten meters or so that are called kibiso. Because the thread is rough and stiff and therefore unsuitable for weaving fine silk cloth, it is usually discarded. With this new material in hand, Iwata changed her approach to making her art. Instead of looking for material to realize a preconceived idea as she had in the past, she now began to investigate ways to use material. The unusual nature of kibiso thread led her to an exploration of line instead of volume. Using dyed and stiffened kibiso, Iwata began making simple container-like forms of very loosely woven thread. The effect, as in Kibiso One (2009), resembles a container form outlined in swirling thread that seems to be unraveling before the viewer’s eyes. Even more dynamic is Entanglement (2011), another work made of kibiso thread, but this time with pieces of rice paper wrapped around it and embellished with splotches of dark paint. More mound-like than container, Entanglement, as the name suggests, also seems a bundle of swirling energy, of something on the cusp of either coming into being or collapsing into formlessness.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Entanglement, 2011 kibiso, dye 13 x 16 x 12 in. |

Exploring kibiso fiber eventually led to another series that Iwata calls “Chrysalis” after the hard case in which the silkworm grows. In these works, the kibiso fiber also outlines containers—oblong shapes reminiscent of unshelled peanuts, though much, much larger. However, because the weaving is also so open and linear, the effect suggests lines in space rather than solid form. Reminiscent of the silkworm’s cocoon (Iwata’s homage to the silkworm), they are intended to be hung on the wall. Chrysalis (2010) is the first piece in the series and was shown at the Japan Society’s gallery in New York City and finished touring in Europe at the Japan Cultural Center in Paris in May 2015. It is the largest work in the series at seven feet tall and probably the most complicated, having several overlapping sections of differing shapes. The work took on a new dimension when one day, while looking at it hanging on her studio wall, Iwata noticed the intricate shadows cast by the thread and decided “to harvest the shadows as well.” This she did by tracing them onto a large sheet of paper placed behind the sculpture. Eventually she “harvested” the lines of other works in the series, including the shadows generated by Chrysalis Four (2014)—which looks like a series of ten large cocoons hung in a row. The result animates the works, making them much more complicated for the viewing eye to decipher what is real and what is shadow, what is drawn line on paper and what is thread in space.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Chrysalis Four, 2014 kibiso 25 x 55 x 7 in. |

In 2011, Iwata encountered another new material called ogara choushi. Like kibiso, it too is a discard from the silk weaving process, but it comes from the end of the process, not the beginning. Ogara choushi is the stiff shell of silk thread remaining on the bobbin after the finer silk has been used up. It is tubular in shape, about six or seven inches long, and about the thickness of a finger. For the bobbin to be rewound with fine silk thread and the weaving process begun again, it is cut off and discarded. Taking the discarded ogara choushi, Iwata bundled piecestogether (often as many of fifty or more) using French embroidery knots to make small, pedestal-sized sculptures. Sometimes they have rice paper added and are painted as is Fungus (2015), which is 7.5 x 7.5 x 7.5 in.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Fungus, 2015 ogarami choshi, sliver leaf, paint 7.5 x 7.5 x 7.5 in. |

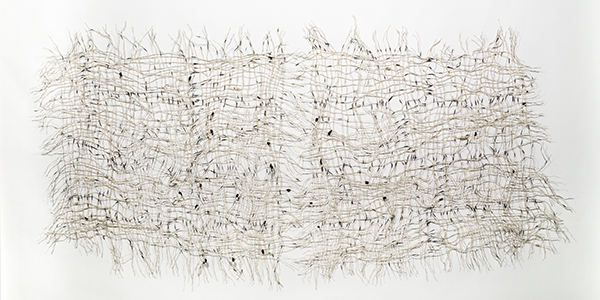

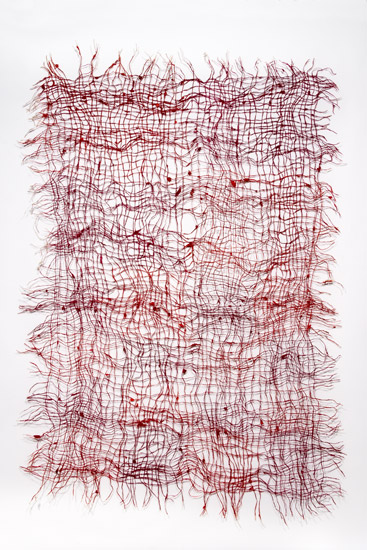

In her most recent work, the “Southern Crossing Series,” she has created flat, irregular grids of loosely woven kibiso thread. Hung on the wall like two-dimensional works of art, they at first suggest deconstructed paintings, a literal pulling apart of the very fabric of the canvas itself. Her intentions, however, have nothing to do with Post-Modernist irony or any attempt to critique the idea of painting itself, but quite the opposite: her works are layered with implied meanings and are much more positive in intention. For one thing, they pay homage to a dying way of life—the extremely labor intensive art of traditional Japanese silk production—while the empty cocoon casings, still attached to the kibiso thread, are intended as a reminder of the thread’s origin.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Southern Crossing Three, 2014 kibiso, paint 55 x 108 in. |

The titles in the series are also laden with meaning. For example, Southern Crossing Three (2014), a large two-panel work with an intricate web of light and shadow created by loosely woven kibiso, suggests the Southern Cross (the Constellation Crux). This allusion to the constellation of the southern hemisphere that points to the South Pole may be a subconscious reference to her move south from New York to Richmond. For her, this is more than a simple change of venue or address; it is a psychological crossing, a return to her artistic origins and a move into another geographical and cultural realm leading to new friends, new ideas, and new ways of being in the world.

|

| Kiyomi Iwata Southern Crossing Five, 2014 kibiso, dye 87 x 60 in. |

Among the things that make Iwata’s work so interesting, aside from her beautiful use of material, is the way it subtly encourages the viewer to reflect upon the contemporary world in which we live. For example, through her exploration of older ideas and techniques, she shows how tradition and the past can still have relevance in the Modern world. Her insistence on the primacy of the singular, handmade object with its many layers of meaning not only becomes a metaphor for the individual in society, but also offers an alternative to a world overflowing with anonymously made objects that have never been touched by a human hand. Every genuine work of art symbolizes the efforts of one human being reaching out to touch another in some important way. Iwata does this, as does every artist working with their hands, by leaving something of herself behind in her work. It is this echoed presence that attentive viewers seek, whether knowingly or not, when engaging with her work. ![]()

Howard Risatti is emeritus professor of contemporary art and critical theory in the Department of Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University. He is the author of five books, most recently A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression (University of North Carolina Press, 2007). His work has appeared in Winterthur Portfolio, Artforum, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and Art Journal, among others.

Photos by David Hunter Hale and Taylor Dabney

Caroline Wright: On Kiyomi Iwata’s From Volume to Line

Process Video: From Volume to Line ![]()

On Evolution: Commentary by Howard Risatti