Fugitive Materials

artist talk captured September 23, 2014 at Virginia Commonwealth University

[George Ferrandi’s talk opened with the following video.]

Videography by George Ferrandi

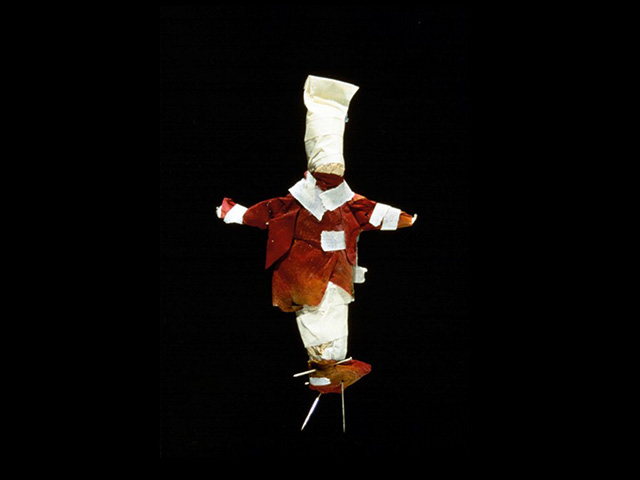

This is going to be an overview of the work I’ve done since graduate school. I was at Skowhegan between my first and second year of graduate school, and I gave myself an assignment to make three pieces a day before lunch using materials I had readily available.

|

I limited them to paper towels, masking tape, straight pins, and flower petals. What I noticed was that the first one was usually awful, the second one would be pretty good and inventive, and the third one would be kind of a cheap imitation of the second one.

|

I also noticed over the course of the summer that the pieces got more and more sparse. They started out pretty dense, and then they pared down. And that was super exciting— for example, with this one on the far right, you could put your fingers in the holes of it conjured up a floppy but very complete bird.

|

I think that exercise cleared a path in my aesthetic to make this piece, also at Skowhegan, at the end of the summer. I borrowed the dock that was usually anchored near the dining area where all sixty-five residents eat. Some friends who really didn’t know what they were getting into helped me paddle it to another part of the lake in the middle of the night, and erect this steel structure that I had been welding secretly at night all summer. Then we pinned a sheer fabric to five sides of it.

|

The plan was that we would just paddle it back and surprise everybody at dinner. We hadn’t accounted for the fact that we had made a box kite, essentially, so the wind just took us. We had no motor, no rudder, no anchor, and just one oar, so we were really at the mercy of whatever was going to happen. Eventually we were rescued by a mom and her two kids in a motorboat, who towed us back.

The piece was really a big deal for me. I loved that it started out as a kind of misdemeanor crime, and then it became this sort of quilting bee with these two people I didn’t know that well, and who eventually became my close friends, and then it was an adventure and a rescue mission. And then, most importantly, I thought I was making something that was a metaphor for lots of things, privacy being one of them, but it turned out to be the thing itself, in that people would swim out there at night with their sleeping bag in a trash bag and sleep there. One of the faculty members, Mel Chin, put his dinner on a raft and paddled out to the house just to have a quiet dinner alone.

|

There is a special kind of connection that happens when you’re in the space of making with other people. The house piece was the first time I had ever done that, where art making wasn’t a singular and solitary experience. That would continue to affect me, most obviously in this next project.

|

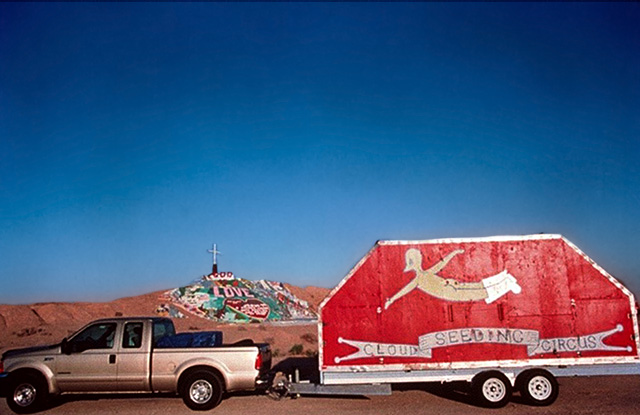

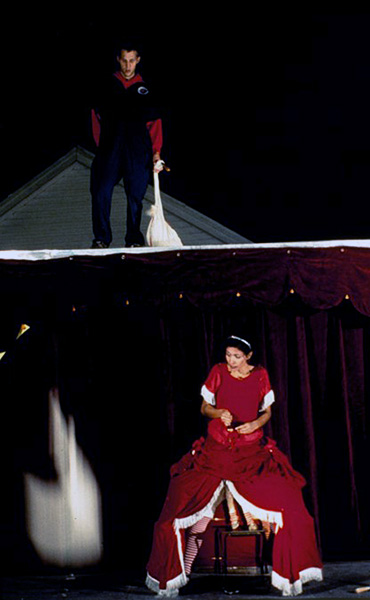

This is the Cloud Seeding Circus trailer, and we’re parked in front of the “God Is Love” Mountain. We were a touring performance group of about a dozen people at any given time. This trailer started with a flatbed, and we built it into a trailer that folded out into the stage for our performance.

|

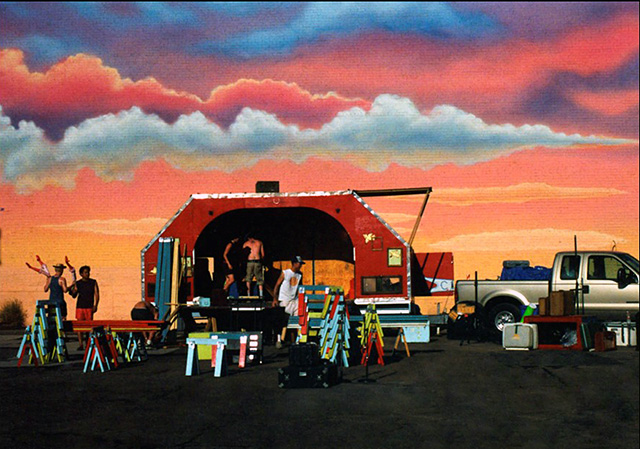

Here it’s parked in front of a mural in Phoenix as we’re setting up. We’d bring our own sound equipment, seating, and all of the objects that we needed for a two-hour show. It was a three-hour setup, two-hour show, three-hour breakdown, and then we’d sleep on Punk Rock Amy’s floor or on top of the trailer, and then drive to Albuquerque or Tucson or Memphis the next day.

|

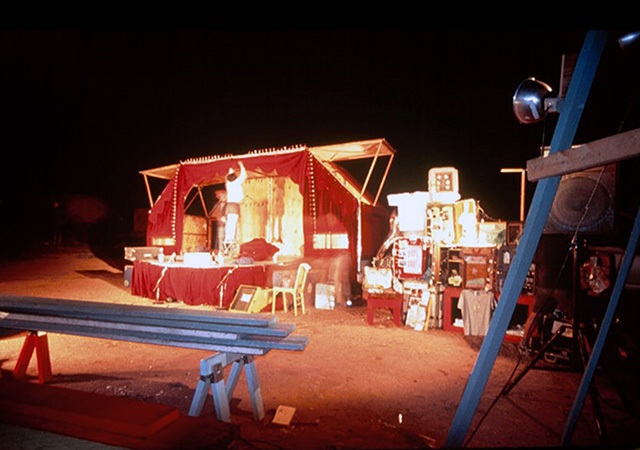

We’d put up our curtains and our lights and our souvenir stand that we called a fink stand because, in the language of the circus and the lingo, broken souvenirs were referred to as finks. All of ours were a little wonky, so we thought of them all as finks.

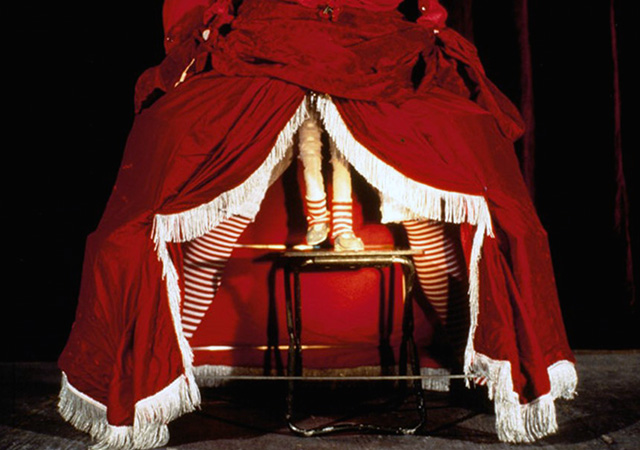

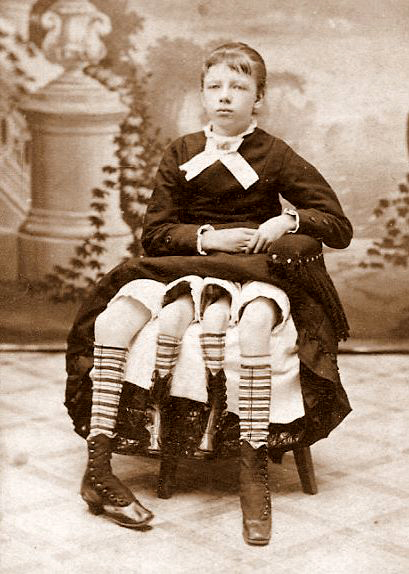

The show was very self-aware. It referred sometimes formally to the structure we were performing on, always to the historical circus but sometimes to specific acts. This piece is a tribute to a sideshow performer, Josephine Myrtle Corbin, who was born with two separate pelvises and four legs.

|

|

In my homage to her, I played the ukulele, and the ukulele puppeteered those smaller legs so they tap danced on that stool.

|

This is a promotional image of Ms. Corbin.

|

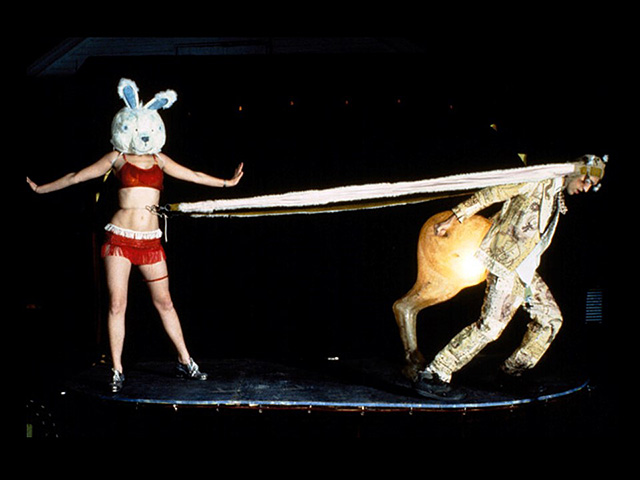

Sometimes the circus references were less obvious. This one was inspired by Chang and Eng, (the original twins from Siam) and their inseparability.

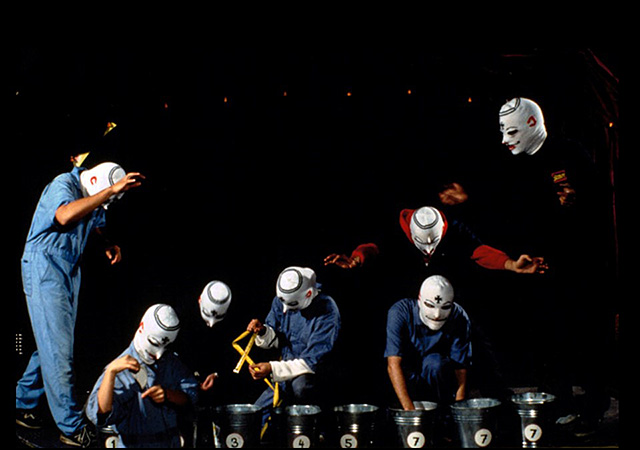

We also were critiquing the historical circus with this piece and, by degrees, the culture at large. Historically, the circus clowns were always hobos or tramps, people without a lot of money being laughed at by the general public - people with enough money to buy the ticket to see the show. We inverted that and our clowns were Georgian-era gentry being laughed at by the general public.

|

There was often something of a quilting bee involved. In projects like this one, we all did small drawings based on Sailor Jerry tattoos and then whip-stitched them together into the suit of armor for this shy character. That character is played by John Orth, who is a really wonderful artist and and musician and currently in the graduate program at VCU.

|

The character on the left is Kelie Bowman, who went on to start Cinders Gallery, and John and Kelie ran a gallery in Gainesville called F.L.A.

|

|

We tried to put the backstage moments, the sort of awkwardness that surrounds performing, front and center, which seems familiar now, but at the time people really didn’t know what to do with us. We were very okay with that.

|

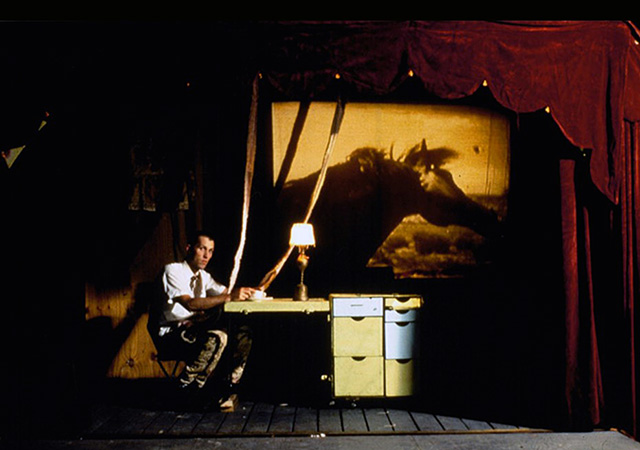

This piece, for example, critiqued itself. (This is David McQueen, who is a VCU alum and shows with the Kim Foster Gallery in Chelsea.) Those shadows were prerecorded projections, and one was agitating, “Seriously? All you’re going to do is juggle? All this set up and then you’re going to juggle?” The one on the right was arguing to “Just give the guy time. See where he goes with this.”

|

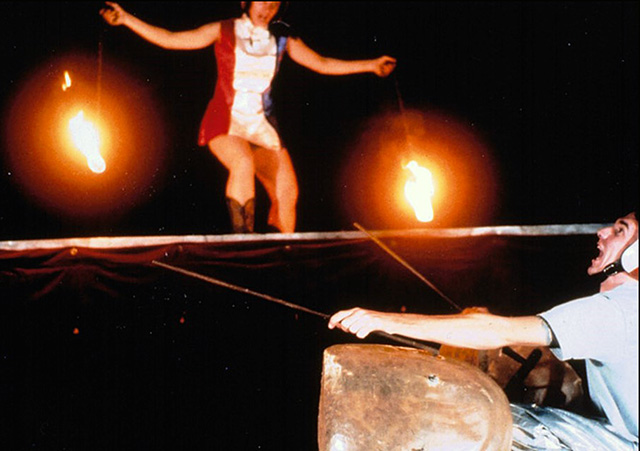

One of my favorite descriptions of it was by a reporter who said it was like Ozzy Osborne meeting Princess Leia and Andy Kaufman at Coney Island. That rings true for me. The performers here are Jesse James Arnold and Christy Gast.

|

None of us were experienced performers. We were all, for the most part, introverts. There was a fair amount of pain in getting onstage, but we called ourselves a “Circus of the Performative Object.” We were making objects that really needed interaction to be at their best life. They weren’t that interesting just hanging in a space unattended. We embraced the awkwardness caused by our lack of performance interest. We were proud to “not distract the audience with any actual skills.”

|

Once, we were brought by a theater group to do a show in Athens, Ohio.

Afterward, the guy who brought us approached with a yellow legal pad full of notes and said something like, “I think you guys have a lot of potential, but you need to tighten it up. For example, right off the bat: Never ever, ever, ever tap on the mike and say ‘Is this thing on?’ unless it’s supposed to be some kind of joke.” And we had to tell him, “Yeah. It was supposed to be some kind of joke.” You could just see his mind ratcheting through all of the other criticisms he had listed on his notepad . . .

|

This is us, outside of Nashville I believe, fixing yet another roof leak.

|

This is a portrait of us taken by Leonard Knight, the artist who hand-painted the “God Is Love” Mountain and died in 2014.

|

~

|

This is a piece by Jackie Winsor. This particular piece had layers of wood, metal, glass, more wood, and paint, and the artist dragged the whole thing behind her car. She imbued in it an authentic experience and a genuine patina—she extended its narrative and her relationship with it. She’s considered a minimalist. I think now, looking back, we had similar aspirations for the objects of the Circus.

|

The whole elaborate set-up: the trailer, the three tours across the country, Punk Rock Amy’s floor, Jesse and Christy arguing about who needed to wear more deodorant in the car—all of that was a way to imbue the objects with an authentic history and an extended narrative.

|

Our project and a lot of other interesting approaches to the circus are chronicled in this book, Freaks and Fire: The Underground Reinvention of the Circus by D. Hill.

We were all doing our own work at the time. I was make installations. A lot of installations, by their nature, are performative, in that you’re aware of their execution and their eventual demise as you’re standing in front of them. This work was definitely along those lines. The materials were fugitive and you couldn’t not think about the short life span of the thing.

|

I moved to New York, which precipitated the ending of the circus. It lasted about four years; there was just a limited and magical window where we all could be in the same place and afford to do this insane thing.

|

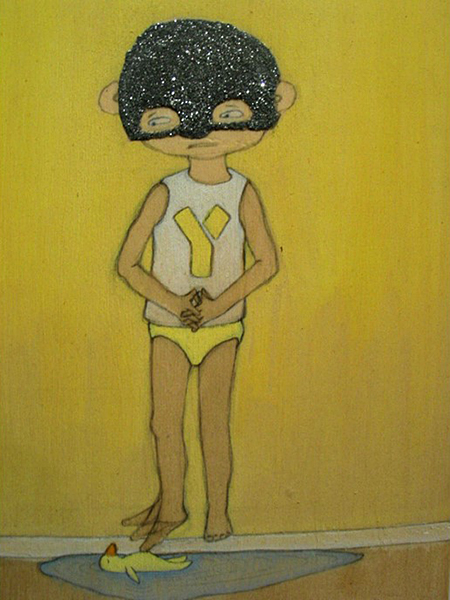

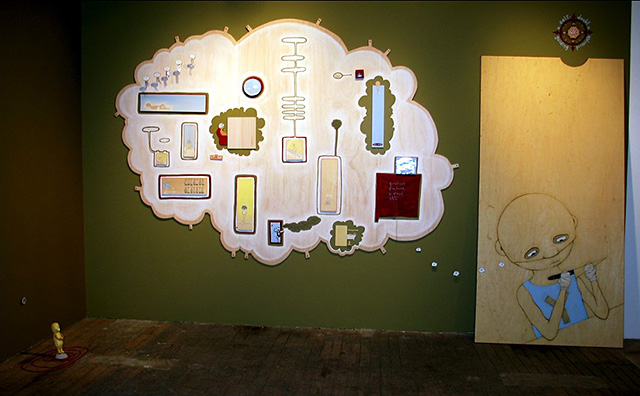

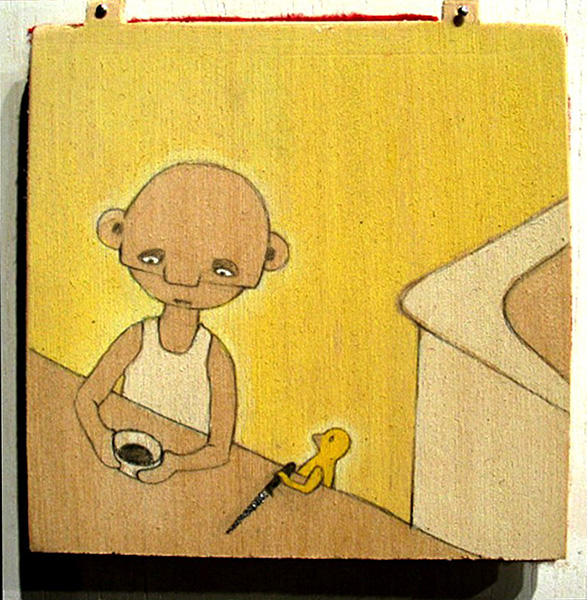

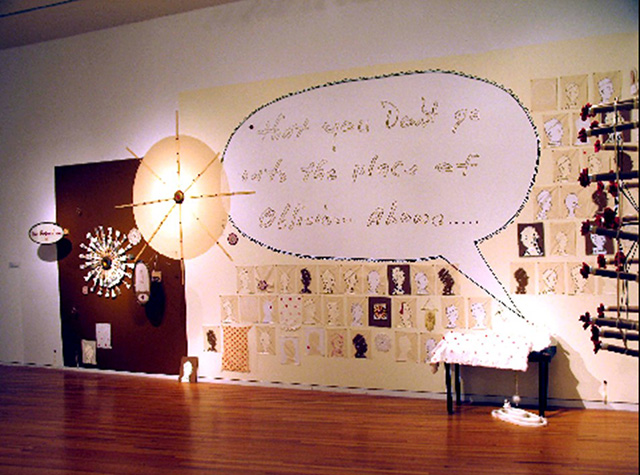

When I arrived in New York, I was making installations similar to this one: experiments in narrative that featured introductions to specific characters.

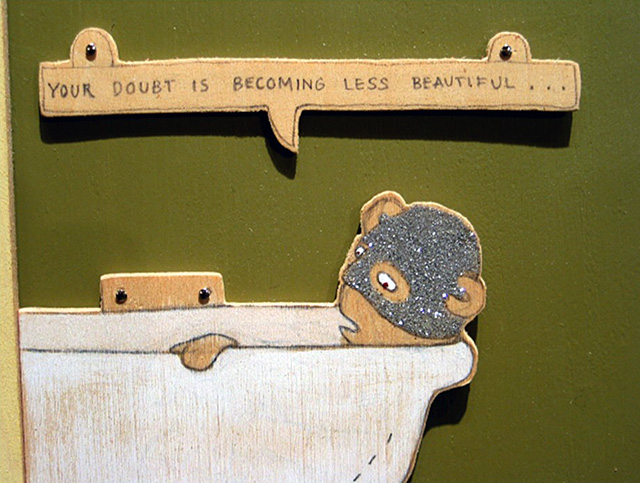

This is Super Silver Monkey, he’s a failing superhero with adrenaline-induced memory loss.

|

|

He has the power of telempathy; he senses a crisis and rushes into help, but it always turns out to be an emotional crisis and he’s not skilled to handle those situations. But he keeps forgetting that until the adrenaline wears off and he realizes he’s failed again…

|

Each installation was an attempt to develop a dossier for that character or others in the series, or to map out their relationships with each other. What I’m still really interested in about this work is that it’s not a linear narrative.

|

To me it feels like reading a book and writing it at the same time. Ideally it feels like that for the viewer, too.

|

They’re able to connect these parts in the same way I am when I’m making the installation. It feels like it’s happening in real time instead of a record of something that’s already happened.

|

I worked with those characters for a couple of years. That whole series is chronicled in Blackbird, VCU’s online literary magazine.

|

After several years of working with these characters, my dad died two months before my first solo show in New York. There’s nothing quite like watching a human being take their last breath to make drawing cartoon monkeys seem frivolous.

|

I needed to process his death, and I wanted to make a tribute to him, but my dad was not a classic hero. He spent some time in jail. He spent some time with the mafia. He was a volatile character who mellowed and became fragile as he got older. He adored me and I adored him, but it’s a complicated kind of memorial that I wanted to make.

|

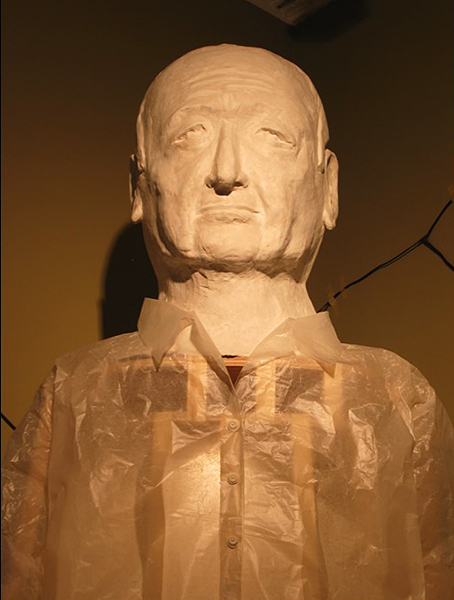

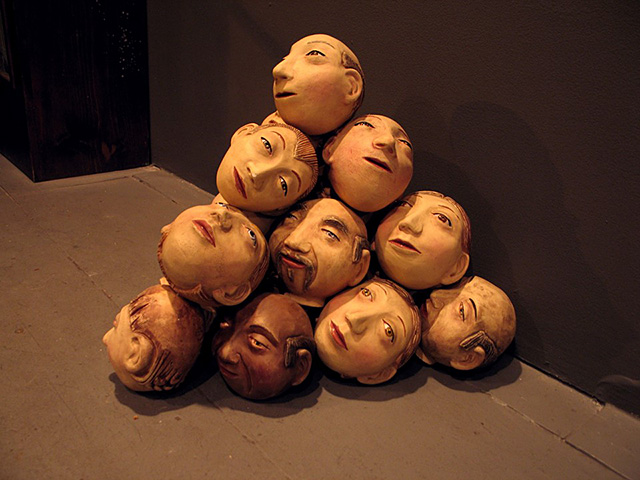

I based the structure on processional saints that have beautifully articulated heads and hands and a very simple, lightweight understructure because they’re to be covered in fabric, and you’re never supposed to see that part.

The figure of my dad faced this entourage.

|

|

This is called “all the ones that have arms are saluting.” They’re mostly cast plaster, some are carved soap.

|

I was looking at things like this. I’m always interested in things that maintain the delicate balance between vulnerable and terrifying.

|

|

|

|

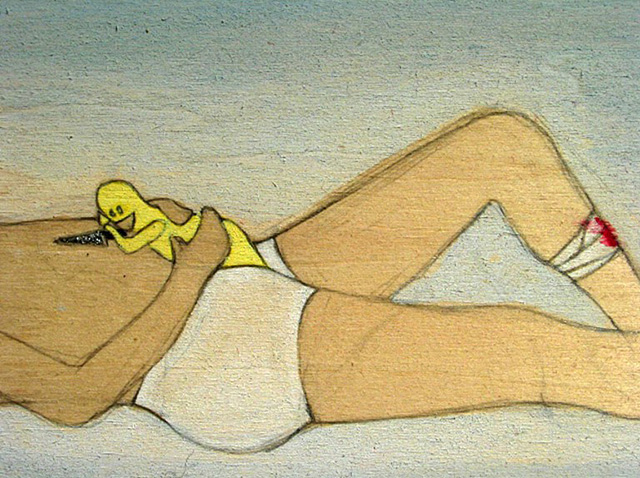

And while I never felt compelled to go back to the Super Silver Monkey stuff, I did want to close that narrative in its own language.

|

|

|

My dad’s death forced me to admit that a lot of the dynamics mapped out in this series were based on family dynamics—and I also had to recognize the parallels between Super Silver Monkey and my dad, or Super Silver Monkey and me.

|

I’d been invited to do a drawing directly on the wall at a show in New Orleans.

Hurricane Katrina had just happened; this was less than a week after, and the school was determined to get back to “business as usual” and establish some normalcy.

|

|

I wanted to make a drawing that acknowledged both the unmasking of Super Silver Monkey and the fact that we were in this town of parades. I also wanted it to carry the sober tone of that current moment - both the region’s and my own.

~

|

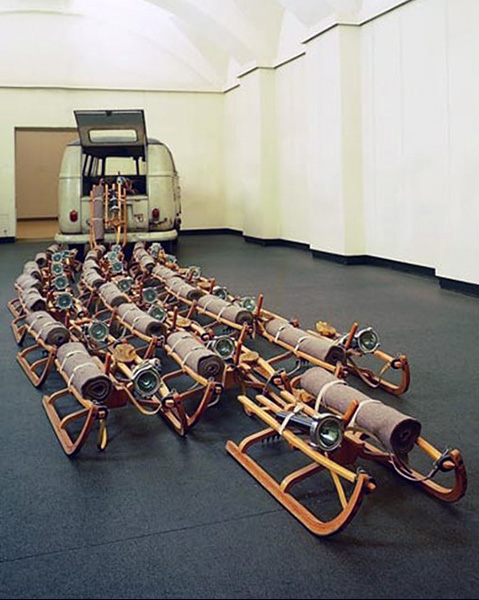

This next installation is informed by this work by Joseph Beuys. He’s packed the tools for survival (according to his own lexicon) onto sleds pouring out of the back of a van.

I was thinking about this and also the Chinese tradition of making out of paper all the tools for survival you will need in the afterlife.

|

This is a store in Chinatown, you can get pretty much anything you need: cellphones, cars, servants, microwaves, etc, all intricately made out of paper.

|

This is my friend Victor’s brother posing for a photo in one of the places specifically allocated for you to set up all of those paper objects for your loved ones, and then burn the objects so that they join your loved one in the afterworld.

|

|

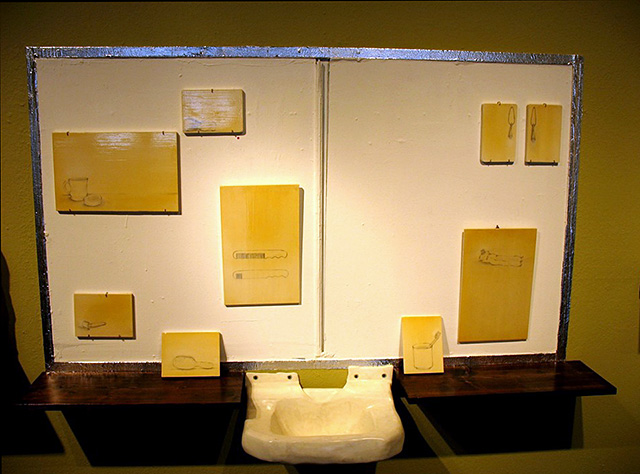

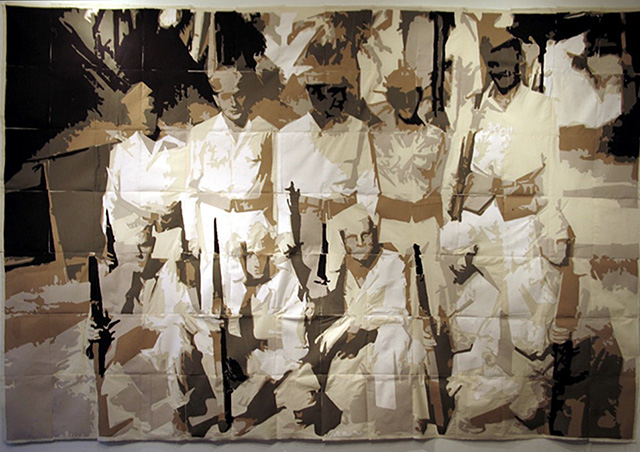

This is my dad’s van—in the last couple years of his life, he sold fruit and vegetables on the side of the road in Baltimore.

|

I parked his van into the gallery and installed these icons pouring out of it - things I imagined would be the tools for his survival. I really came to an understanding of what that urge is about - sending the objects onward. Partly as a gift, but also because any loneliness inherent in the object surfaces in the context of death.

|

|

|

The next couple of images, I really debated not showing you. For the last couple of days, I’ve thought, “I don’t have to show them everything that’s difficult.” They’re not difficult because of the content; they’re difficult because they embarrass me. So I wasn’t going to show them, and then last night, I dreamt that I was at my mom’s house and there was a lion in the front yard. I said, “Mom, there’s a lion in the front yard!” Then there were two lions, and I said, “There are lions in the suburbs!” And my little brother just opened the door, went outside, and sat next to the lion. Then he had this little kitten, and he held up his beloved kitten to the lion’s mouth, and the lion just licked it. I woke up and thought, “Dude is a Republican, they’re afraid of everything. If he’s going to do it, I’m going to do it.” So, I’m going to show you these pieces even though they’re embarrassing to me, and I’ll explain a little bit about why they’re embarrassing.

While my dad was in the VA hospital, he was cold and asked for a blanket. They didn’t have any on that floor; they looked on the other floors, and they did not have a blanket in the hospital—the Veterans’ hospita—for my dad, who was dying and who fought in World War II and was a soldier. We could have gone to get him a blanket or something, but we didn’t know if he’d be alive when we got to the parking deck. This was what might rightfully be considered a “haunting moment,” and something that, if you’re not a religious person (which I’m not), then possibly only art can approach. So I wanted to make him a blanket. What is embarrassing to me about that impulse is not that hopefulness of it, or the too-little-too-late-ness of it, but the fact that I screwed up the ratios between those things and the form.

|

|

In general, I always want my work to negotiate between a narrative space and a formal one. How does it get to the ground? What does that mean to the story? But I wanted this particular piece to also serve a purpose in an invisible realm – I wanted it to psychically “right” that situation. It fell short on all three counts. I reverted to this fabric because of the Chinese tradition, but that had nothing to do with my dad or with the rest of the iconography. Ultimately, I think this object reduced this profound experience to a caricature.

|

For the next few years, I was dealing not just with my dad’s death, but with the reality that death was no longer an abstraction in my own life. I kept trying to make this blanket and right that psychic situation. I tried to do it again, this time making the blanket in the same language as the other objects, but it was still just as dumb.

|

So I did it one more time, devoid of other imagery, and this time using my dad’s clothes. It’s an image of him and his war buddies right before the war. It’s an actual padded quilt, not just a symbol of one. I feel like this one finally worked on all three of those levels where I was trying to get it to operate.

~

|

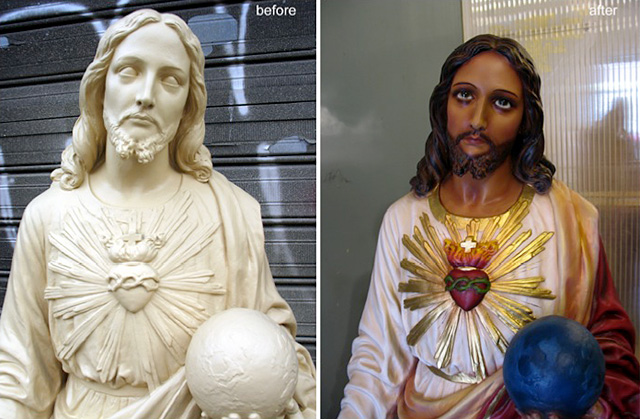

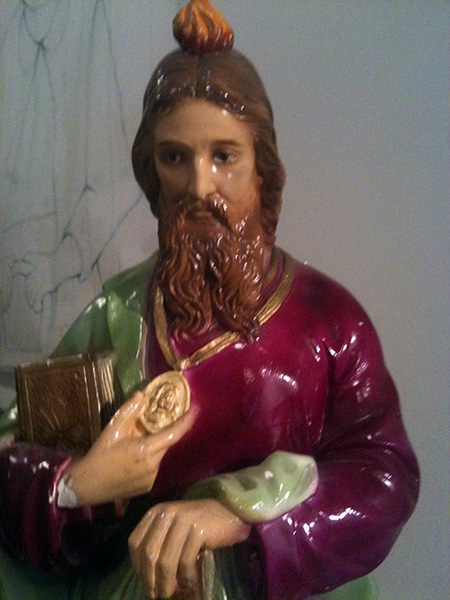

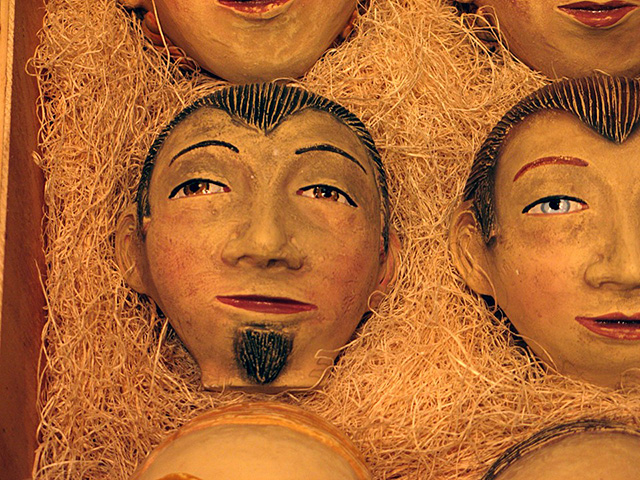

The whole time I’ve been in New York, I’ve been running a business that specializes in the restoration of statues of saints for churches. I am still just completely undone by the relationship people have with these objects. Plumbers would come into my studio, blue-collar guys, who normally would leave aesthetic decisions to other people, and they would have color swatches and fabric samples and very specific aesthetics in mind when it came to these objects; the kinds of decisions that they really didn’t prioritize in other facets in their lives

|

A lot of what I was doing was reconstruction, repainting, sometimes making Jesus’s skin lighter, if he was going to a church for white people.

|

Or making his skin darker if he was going to a church for people of color.

|

I mostly deal with Catholic priests, occasionally deal with really amazing, self-invented Catholic pastors. Like these women who took over a storefront in Brooklyn and made it into a church. They mounted a ship’s steering wheel to the ceiling because they wanted to steer their people to God. In their basement was this aquarium at least twelve feet long and it had just a little bit of water, and more than twenty of the biggest turtles I’ve ever seen in my life. Right behind the altar was a red room with a bed in it and a lamp. So if someone in their congregation was sick, they could stay there, and anyone in the congregation could cook for them or come to visit them without entering into their private space. It was amazing, really beautiful, and sort of what I would wish for in a church as a non-religious person.

|

They gave me this; they told me I would need it someday.

|

I asked them for what, and they said very dramatically, “Oh, when you need it, you’ll know.” So I guess I’m just going to have this around for a while . . .

|

This is one of my favorite restorations. This is an actual reliquary. This circular window is glass and behind it is a relic—either a fragment of bone or a fabric from the human being that eventually became canonized as St. Paulinus.

|

This object would also have would have been used for processions, meaning it would have been taken in and out of some storage space or display case, but apparently it was just a little bit too tight of a fit.

|

So they cut off the corner of the book, which is the Bible. That in itself was a funny turn in prioritization to me. Then, while restoring the book, I realized that they used a real book. Peeling back the damaged paper, I saw these gold spears crossing each other in what looked like it was kind of masonic iconography on this thing that was supposed to represent the Bible.

|

So it started to get really occult-y. Is that an adjective? Occult-ish? But it turned out to be a guidebook to knitting, and those were knitting needles.

~

|

I have one more statuary story. There are so many that are amazing. This is St. Jude—he is the patron saint of lost causes.

|

So when it doesn’t work to bury the statue of St. Joseph in your yard when you want to sell your house, you pray to St. Jude.

|

This is a totally crappy statue that would cost about thirty bucks, had a really terrible paint job, and was such a bad plaster cast that the walls weren’t an even thickness, so someone probably sneezed and a section of the torso collapsed.

|

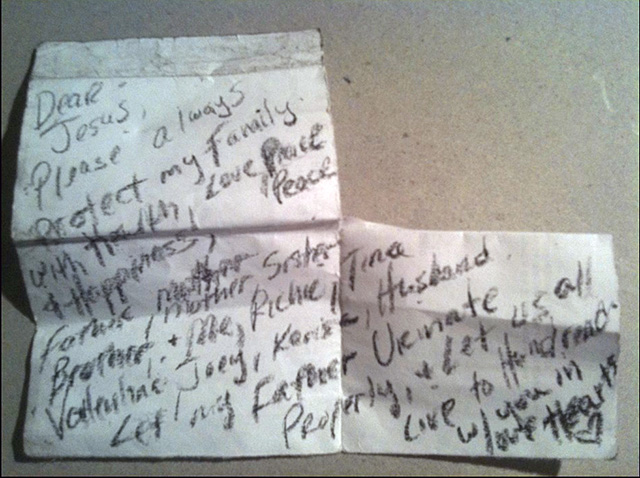

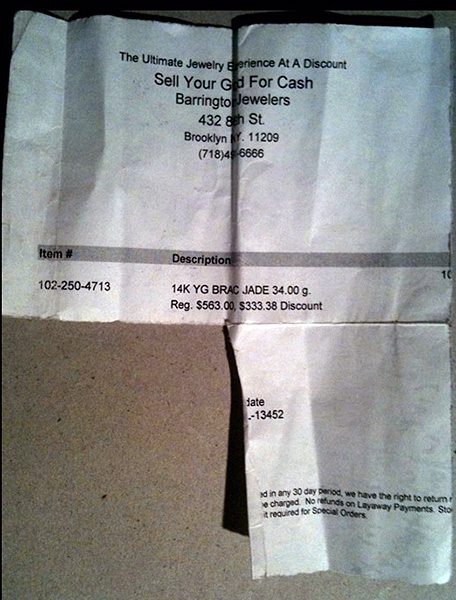

But people in the church revered it, and so they asked me to fix it, and inside of it was a dollar bill and this note.

|

Dear Jesus, please always protect my family with health, love, peace, and happiness. Father, mother, sister, brother, me, Richie, Tina, Valentine, Joey, Kira’s husband, my father. Let my father urinate properly. And let us all live to a hundred with you in our hearts.

What else do any of us want, really? To urinate properly and live to a hundred. I did what you would do: I put the note and the dollar back inside and fixed the statue.

|

The only thing more poignant than the note itself is the fact that it’s written on a slip from a pawn shop slip. It’s such a complete narrative in itself, right? It’s complex, and it’s just everything.

|

Sometimes when I came home, there would be a bucket of body parts on my step. If I ever got a package delivered, it would get stolen immediately. But if someone left an appendage, it would stay there until I got home. That definitely influenced my work, just thinking about the invisible figures attached to the limbs and the perpetual strangeness of their absence.

|

This was right before the 2008 election where Obama won. I was thinking of revolutions and ammunition and the toppling of statues. I was optimistic.

|

|

|

|

|

|

I used the same processes involved in the statuary, so these are cast plaster and painted. The more they chip and break and the more they become archives of their own history.

|

One of the things probably most influential about that work was witnessing the processions of the statues on the day dedicated to that particular saint, called their Feast Day.

|

The people who are dedicated to that saint process them around in the streets and sing songs and sometimes distribute bread. They attach money to the saints. It’s amazing. It makes me so jealous.

|

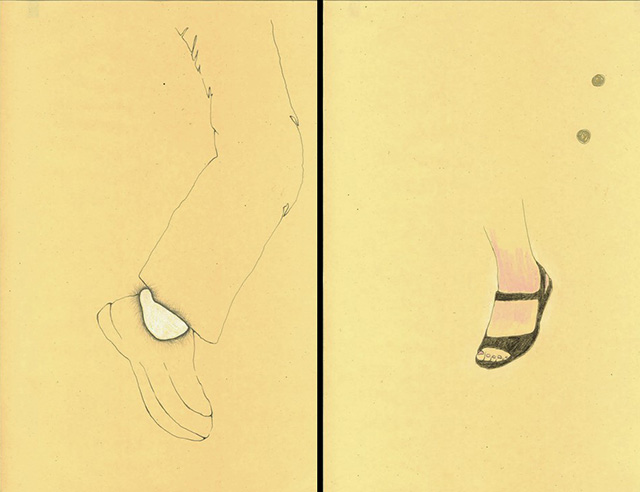

This is a statue that I restored for its one hundredth anniversary. St. Anne, in Hoboken. She’s the patron saint of women and it is women who carry her in the procession. They make these blue pillows to support the weight. Since the restoration was right before her centennial anniversary, they invited me to be a part of the carrying crew.

|

I showed up and saw the women’s shoes and thought, “Oh my God, I’m going to be doing the heavy lifting here. Like, seriously you wore pumps?” I carried it for about a block before I could feel my spinal column torqueing—the kind of pain that I knew was going to be irrevocable—so I traded out my spot. Meanwhile, those women in their pumps and flip-flops carried this four hundred pound thing for four hours.

|

It’s amazing and it makes me totally jealous. I’m jealous of the fact that here is this group of people all connected by a shared narrative, and they’ve taken to the streets, and this sculpture is their rallying point. That’s what I wanted to do.

|

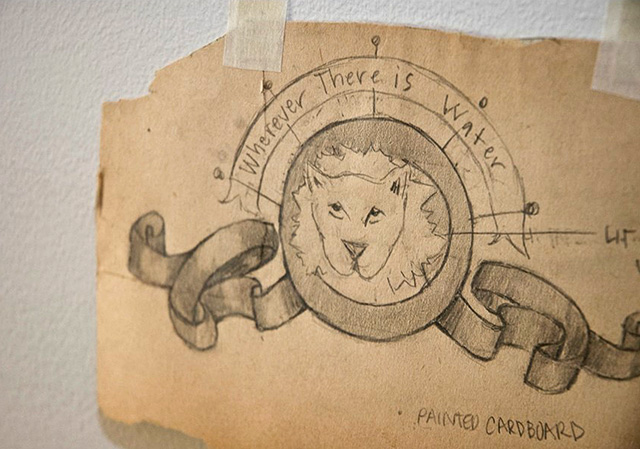

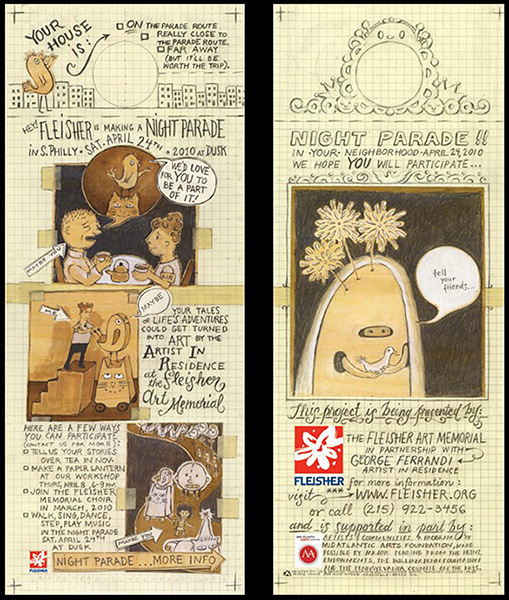

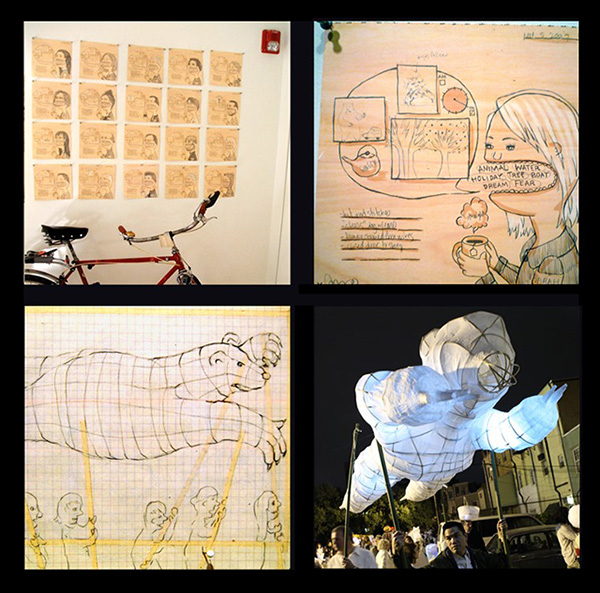

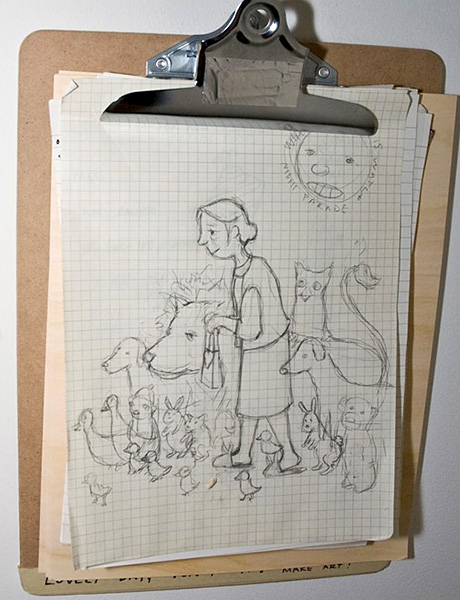

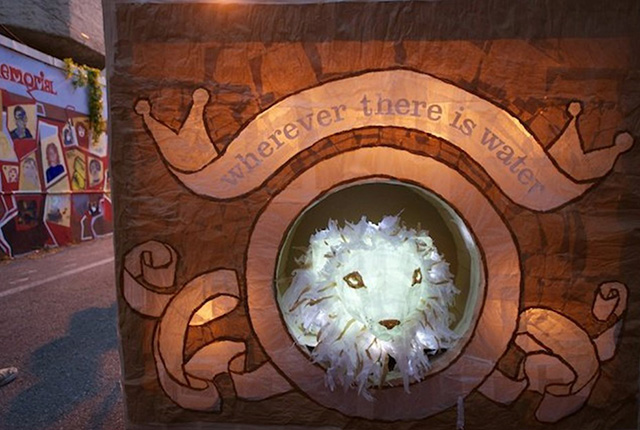

I got the opportunity to do it in Philadelphia, at the Fleisher Art Memorial. I wrote a fictional narrative called Wherever There Is Water. It’s about an elderly woman named Huberta who gets separated from her partner of fifty years and taken to central Florida against her will. She starts working her way back to New York and begins a series of adventures.

|

|

We introduced people to the project through these door hangers that we put out months ahead of time. They told people if their house is on the route or near it, and also how they could get involved. We put them all around the general route area.

|

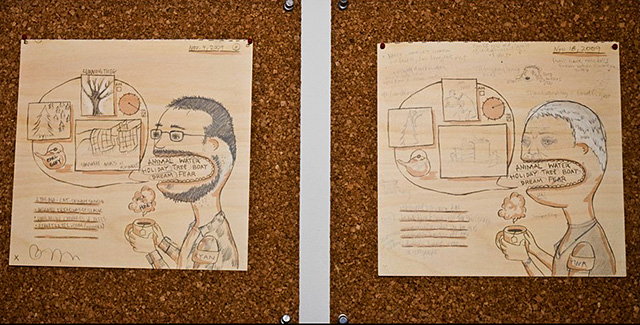

Through that and other methods, we also invited people to talk to me.

|

In the narrative I’d written, there was a gap where I could fold in parts of other people’s stories. So it was a way to really genuinely engage with people from the neighborhood and translate some of their stories into this procession that was going to go through their neighborhood. At each tea party interview, there was a really structured interview, and from those conversations, I would generate images that would translate into objects.

|

|

|

|

The way that I could share the narrative with those people, who didn’t grow up in the same faith in this fictional story, was by hosting several lantern-making workshops. In addition to giving them instructions about how to make lanterns, I’d tell them the story about Huberta.

|

We formed a choir and wrote songs and those also told the story to passersby. Then there were textboxes that allowed the possibility, if you were standing on the corner as the procession walked by, that you could see the story unfold in front of you.

|

These are two VCU alumni carrying the main banner.

|

|

|

This is the main character Huberta and another VCU person, David McQueen.

|

|

|

|

|

I would go to karate clubs, break dancing groups, Korean drum sessions, any community organization who would have me, and I would tell them the story, and they showed up. So during the staging and trying to figure out who would go next, who would carry what, these kids suddenly surrounded her, and they were just like, “I don’t know who you are, but we got this.” They became her guardians.

|

|

|

|

I’m going to show you just a minute of this video, which was made by someone in the neighborhood, Pete Marshall. It’s his band; they covered this song. He shot the footage and edited it. It’s way better than anything we hired folks to do. I’m just going to show you a few minutes of it.

Videography by Pete Marshall

|

|

|

|

I’m still obviously using these readily accessible materials that to me have a kind of urgency about them but that I also think are really beautiful. These are some of my favorite images from that project, now that these objects have this extended history.

|

Shortly after that, I lost my studio of ten years. Then my relationship of ten years ended, on the same day, unrelated, and it was definitely a challenging stretch of time.

|

But I took over this studio, this very raw space, in Bushwick, and spent about six months sanding floors and scraping paint.

|

It was a very reflective time.

|

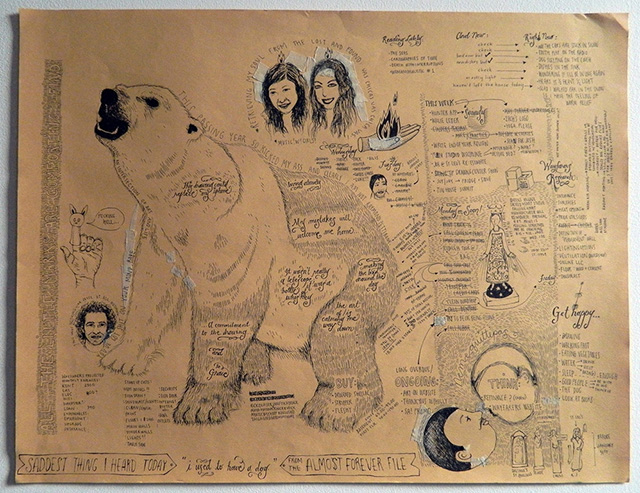

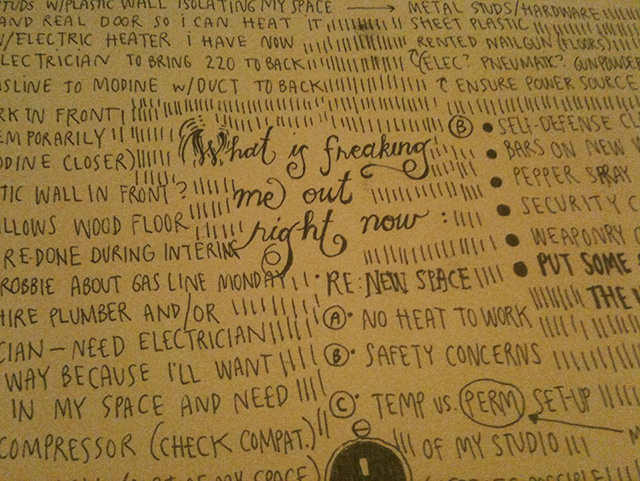

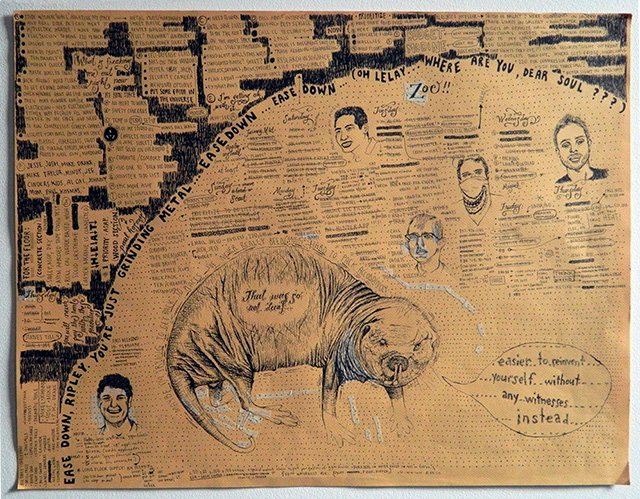

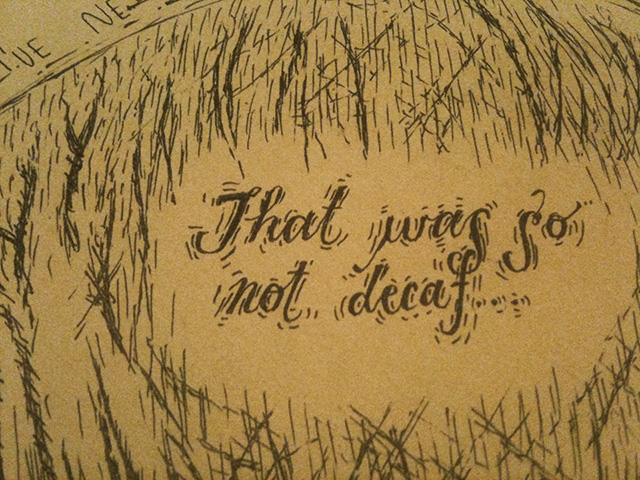

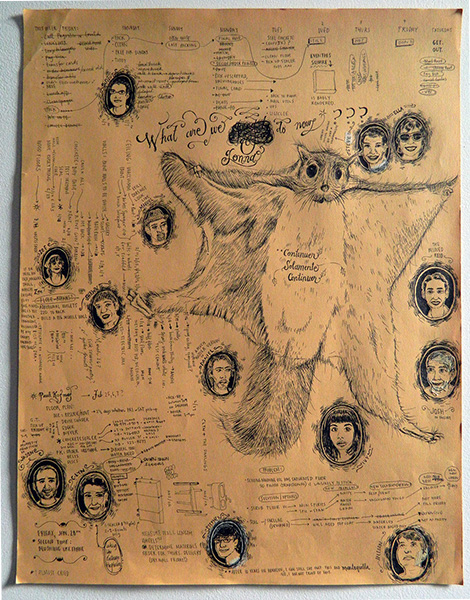

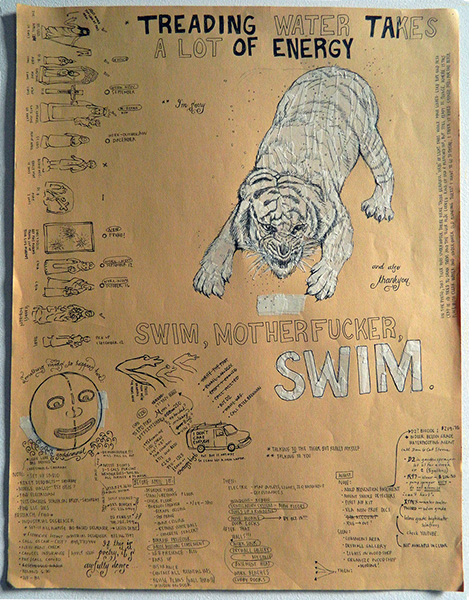

I was doing research related to renovating the space, like, “What urethane is going to stick to a floor that has oil seeping out from the industrial sewing machines that were there for fifty years?” As a way to process the research and to process my anxiety, I started doing these drawings that were really functional tools.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I wasn’t thinking about them as art at all, but I am really grateful for them and love them now. And there are little tributes to the people who were kind of keeping me off the ledge.

|

Coming out the other side is Wayfarers, the studio program and gallery, thanks to the help of many, many people who helped me build walls and paint and administer this. It’s a lovely thing.

|

There are private studios for ten to fifteen artists. There’s a gallery, and you have a residency there for a year, and when you leave you’re eligible for a solo show.

|

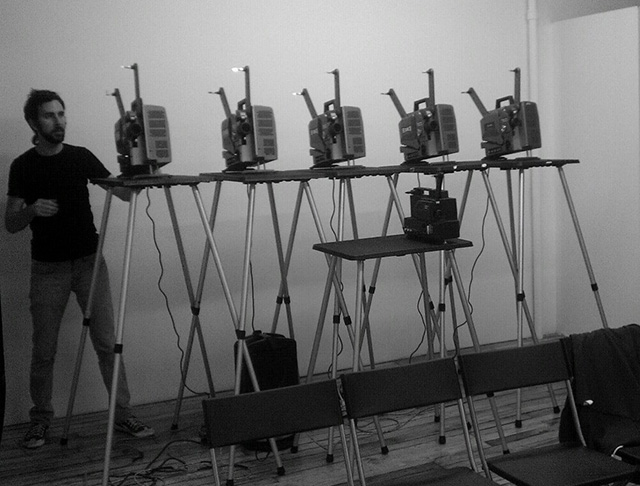

In the gallery, we do performances, poetry readings, and video screenings.

|

This is Roger B.B. doing a six-projection event. It’s a lovely community, many meetings of minds.

|

This is Super Silver Monkey and Omar Little.

That brings us up to where we are now, in the piece which is often described as me sleeping on people on the subway. But that was never how I thought about it at all.

|

|

|

I really think of this sculpturally, that whoever wound up sitting next to me, I would be focusing on the shape of the space between us and in my mind re-sculpting that material, from something rigid and unyielding to something soft and malleable.

And when I convinced myself, “Okay, this is not the space between strangers. I know this person. I love this person,” then I put my head on their shoulder, and we’d see what happened.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some people just let me stay until it was their stop. If there was any opportunity for interaction, I would say, “It felt like I knew you.”

|

|

|

She’s playing Solitaire on her phone. I thought she was lonely. They took a selfie. But she didn’t want it to be over.

|

|

|

This one, I love the symmetry of this one.

|

| [George Ferrandi’s 2014 TEDxVCU Talk, It Felt like I Knew You, also appears in this issue of Blackbird.] |

In case you were wondering why no one noticed a person riding with me and videotaping everything on her phone, it’s because no one cares.

~

This is another project that I’m working on now that I don’t have a way to make look interesting, but I think there really is something happening.

|

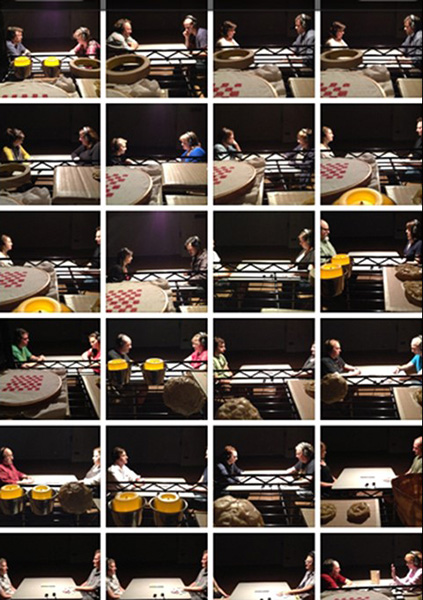

It’s a mediation that I do for two people at a time. It’s about ten minutes. The people sit down at the table, and they’re each given a headset. There are two different ones that I do.

|

|

|

|

One is for two strangers, and I’ll do that over and over again, putting objects in front of them and taking the objects away to direct and misdirect the narrative. At a particular moment in each mediation, I take a photo.

|

I’ll do an eight-hour shift of ten-minute pieces. I’m not articulate about it at all yet, but we are all in these narratives together, and I’m at the service of these people. It’s immersive and real-time, and that’s all I can tell you right now, but there’s something really special about it.

~

This is the last project that I’m going to tell you about.

|

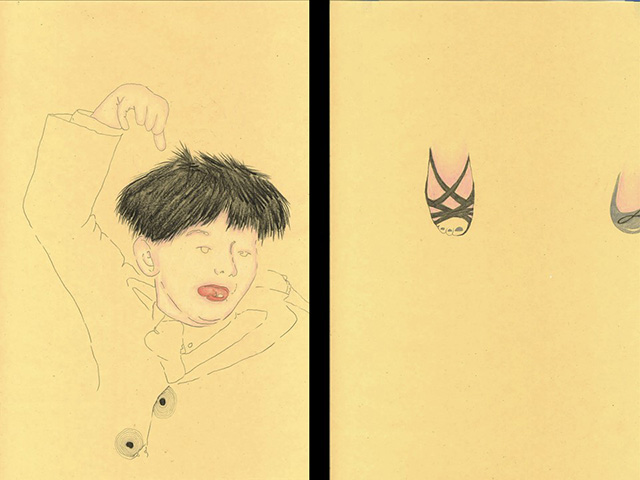

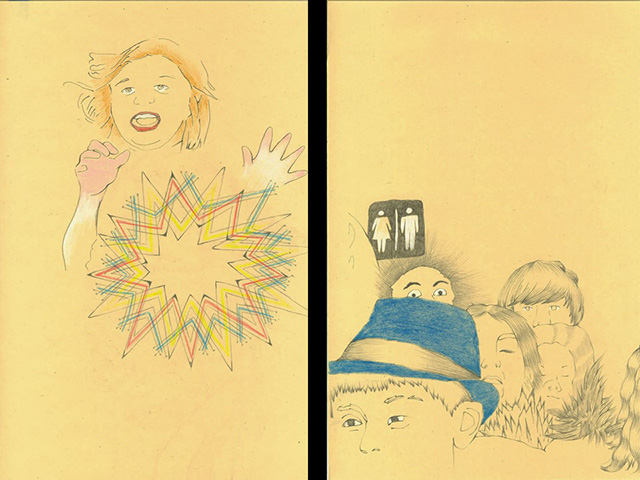

My nephews did not come to that procession that I made in Philadelphia because they went to this bar mitzvah party instead. This picture showed up in my Facebook feed, along with some other photos of the night that were underlit and not so interesting, but this one is like a Tintoretto painting. Like, khaki, khaki, khaki, khaki. This blue and this blue. This pink diagonal.

This ungodly long arm for a child bifurcating the whole image. The arc of motion. This guy with the plié. Peace Nixon here. The air guitar guy.

It’s so beautiful, right? All of them. I just want to inhabit that interval of time, that split second, I want to stretch out what’s happening in the frequencies that we can’t see. You know what I mean? There’s a puppet show that happens here, I’m sure of it. This girl’s phone is reflecting the universe. The only girl’s feet we see, we only see one shoe.

I don’t know. I can’t get enough of it. I can’t even approach it, and I am trying.

|

I have photographed it.

|

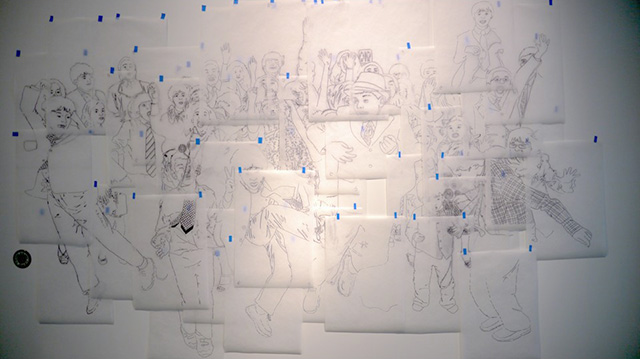

I did tracings of those images.

|

I interviewed my nephew, who was at the bar mitzvah, about all the players, what he remembered. Was there a song playing?

|

|

|

|

I’ve done drawings that try to get at those inter-frequency moments, or just reveal other things that are happening in between the interval that we can see.

Then I get invited by the University of Alabama to do something; they commissioned a project. I proposed to reconstruct that photo.

|

Building custom-fit prosthetics for students, faculty, and staff who were willing to play those kids. The project is called The Prosthetics of Joy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

These are some of those objects, at the service of holding the person for an extent of time in that pose.

|

| video still from “Performing The Prothetics of Joy” |

This is a quick intro to the event that accompanied it. At this point, the audience has never seen the photo, and they were instructed not to take any photos themselves until they heard us say, “Mazel tov.”

|

There’s a musician in the room who just plays at intervals where one of those secret things was happening, and it seemed appropriate. He hasn’t played yet.

There’s that puppet show that I’m sure happened. he people who helped me make these things and were willing to sit for my unprofessional tailoring jobs were just awesome. This balloon guy, he’s just got a bobby pin clipped to his hair, because that character just has one tuft of hair out of place. I don’t know if this is obvious, but it’s really important to me. In the same way that those three-dimensional objects get distorted in the 2D, when we were translating them back into 3D, I wanted to allow for that same breakdown to happen. Instead of painting a pattern on someone’s dress, it is made as a separate object that is suspended in front of that person’s dress.

Understanding where all that stuff fails to line up and how the effect breaks down is probably the heart of the piece.

|

| video still from “Performing The Prothetics of Joy” |

This guy with the big camera is Jared Ragland, who is a great photographer. He was a White House staff photographer. He could read the metadata of the original image and figure out what kind of camera and lens and speed was used. So he replicated all of that. The people held this pose for six minutes.

At some point, if we are ever having a drink together, we can talk about the debate around “Free Bird” that centered from this moment. [See time marker 4:55 in performance video above.]

|

This is the photo Jared took.

|

These are the prosthetics in the exhibition that followed the event. This is what I was talking about.

Blackbird has done this super cool thing where, if you scroll over it, you can see a close-up of both images to compare against each other. It’s very satisfying, right? It’s so good.

Roll over either image below to magnify and compare detail

Original photo by Siobhan O’Brien

Reenactment photo by Jared Ragland

[See Blackbird’s original coverage of Ferrandi’s The Prosthetics of Joy with more images and a process video in Blackbird v13n1.]

Audience: Were you more interested in the objects, or the performance, or the photograph that was the final piece? What was most important to you about that piece?

GF: Could you say that again?

Audience: Yeah. I know the whole piece is important, but there was the performance aspect of it, the collaboration with the people at the school, but then also the actual objects in the photograph. It seems like there was a lot of different parts to it. Was any part more important? Or was there any kind of end you were looking for? Or was it the whole process?

GF: This is the nature of obsession. I wanted to get to a point where I felt like I had inhabited that original image by whatever means were necessary. I moved through those things, increasing the ante, trying to get closer to that psychic job. So I can’t say that any one was more important than the other. I was hoping they would add up into something. I’m still not done, you know? Now this is the nature of obsession. You think you’ve got it and then, “Oh God, how come his elbow is bent like that? What was he thinking?” There’s this impulse to go deeper. I really do, I think it could be a forty-eight-hour event where things happen around each object, each character. Time gets sped up and slowed down.

Videography by George Ferrandi

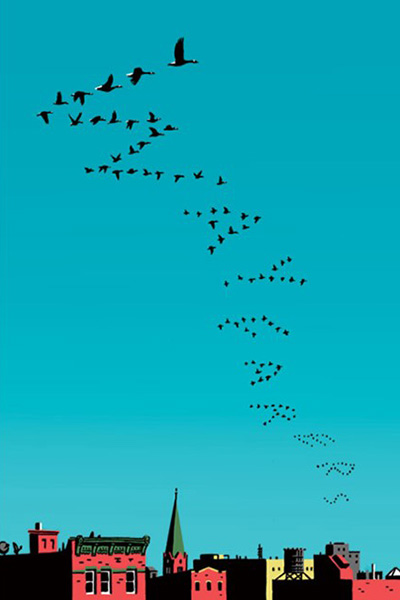

This is the last thing I’m going to show you. This is our departing experience.

~

Production Postscript & Additional Materials

It took Blackbird staff a little longer than usual to transcribe and bring you this 2014 talk from George Ferrandi. We would like to update readers on Ferrandi’s 2015 residency in Japan as a representative of the U.S.-Japan Creative Artists Program, the project she created there, and her most recent work.

|

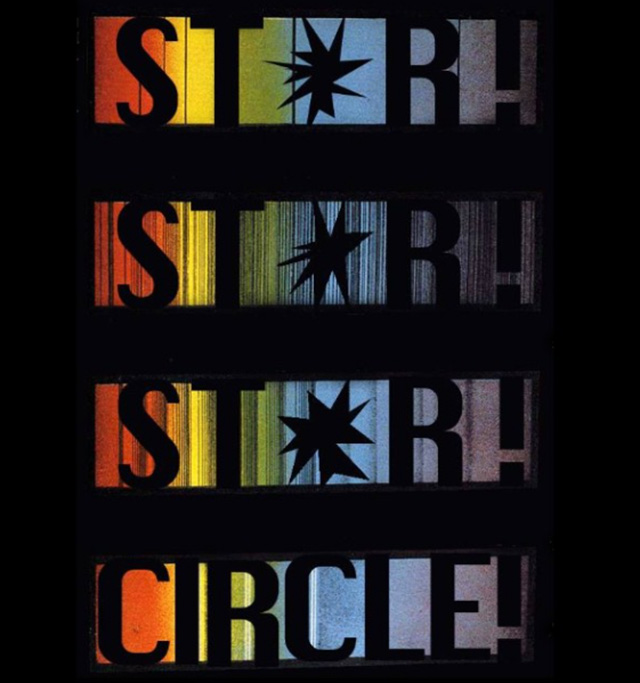

| Star! Star! Star! Circle! Tokyo 2015 Photo by Michael Lindlow |

Since the two-person, ten-minute mediations with objects and audio headphones described in the artist talk, Ferrandi has developed a nine person “synchronized sound play” in the same family. It is titled Star! Star! Star! Circle! and has been performed in New York, Tokyo, and the small town of Unityville, Pennsylvania.

|

| Star! Star! Star! Circle! Wayfarer’s Gallery 2015 |

|

| Star! Star! Star! Circle! Wayfarer’s Gallery 2015 |

Describing the 2015 New York performances is the following from the Wayfarer’s Gallery website:

Star! Star! Star! Circle! includes an immersive, synchronized sound play, as well as sculpture, drawings, and cyanotypes on fabric. This show serves as an introduction to the artist’s work related to axial precession. Regarding Star! Star! Star! Circle!, Ferrandi writes, “The fact that the North Star—what we literally consider our ‘guiding light’—changes, is an allegory worth ritualizing. Our faiths falter, our parents die, but we look to a new star. I'm curious about how a transition of that scale will be marked, and think we could begin planning that celebration now.”

Ferrandi puts this plan into action by first writing intimate myths to be associated with each of the stars that will eventually become the planet’s North or Pole Star. The sound play and the physical works in the exhibition function as introductions to this cosmological narrative and to each of those nine celestial characters. Ferrandi’s . . . work intimates a temporal paradigm based well beyond the human lifespan, incrementally reshaping our relationship with time.

Star! Star! Star! Circle! video

Tokyo 2015

Video by Naoki Takeshi

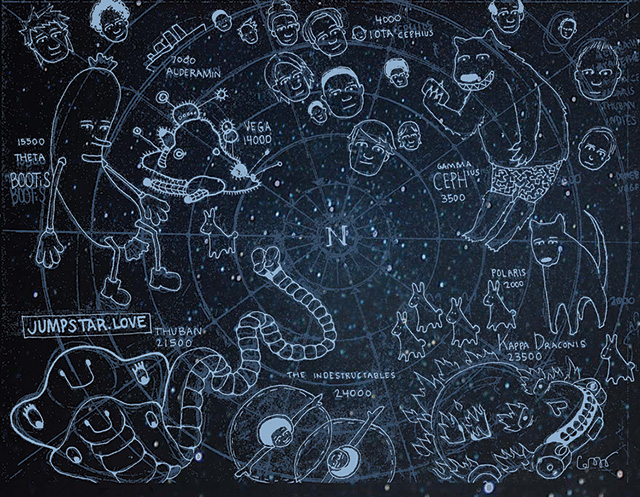

Star! Star! Star! Circle! was also the genisis for Ferrandi’s current project: JUMP!STAR, “a social sculpture culminating in a future tradition.”

|

| George Ferrandi’s rendering of Earth’s anticipated future pole stars |

JUMP!STAR, named after Annie Jump Cannon, the deaf scientist credited with developing a system of stellar classification in use today, is “an attempt to work together to invent the traditions—a thousand years in advance—that can be hypothetically passed down to celebrate the eventual changing of the North Star.”

|

| Jump!Star invites your participation. |

Under the care of George Ferrandi, plans for this future celebration are already well underway. ![]()