Parks at Life: Works from VMFA’s Collection

Sarah Eckhardt, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

These eight photographs by Gordon Parks, which appeared in Life magazine between 1948 and 1967, were acquired by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts between 2012 and 2016. They appear here courtesy of the Gordon Parks Foundation. The photographs were exhibited at the VMFA in the summer of 2016 under the title, “Parks at Life: Works from VMFA’s Collection.” The accompanying text appeared adjacent to the photographs in the exhibition.

The editors at Life never limited assignments for Gordon Parks, the magazine’s first African American photographer. Deeply aware of his versatility, they valued his iconic fashion images as well as his portraits of artists, celebrities, and leaders. But Parks had a strong commitment to social justice and willingly accepted—if not sought out—assignments about race in America, from his first major assignment in 1948 through 1970. Unlike most photographers, Parks often crafted the words that framed his images for these stories. Although his essays have received less attention than his iconic photographs, they make a significant contribution to the literature of the civil rights era.

There was no special black corner established for me at Life. I was assigned to any and everything. But if I could bring significance to a story because I was black, it was given to me. I went also as a reporter—not Life’s black reporter. —Gordon Parks |

|

The photographs in this exhibition are associated with five key essays that span most of Parks’s career at Life: the autobiographical “How It Feels to Be Black” (1963); “Harlem Gang Leader” (1948); “The Restraints: Open and Hidden” (1956); “The Black Muslims” (1963); and “Stokely Carmichael” (1967).

As the civil rights movement gained momentum in the early 1960s, Parks increasingly understood the need to control the story that accompanied his images. The majority of Life magazine’s twenty-three million readers were white, and Parks’s frank narratives and personal insights into the conditions facing black Americans, combined with his images, played a powerful role in changing public perception of inequality and injustice in the United States.

In 1963, Parks published an autobiographical novel, The Learning Tree, based on his memories of growing up in Fort Scott, Kansas. After the book became a bestseller, Warner Brothers approached him about turning it into a movie. Parks wrote and directed the film—which he shot in Fort Scott—thereby breaking another barrier as the first African American director in Hollywood.

~

“How It Feels to Be Black,” Life, August 16, 1963

In the August 16, 1963 issue of Life, less than two weeks before the March on Washington when Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, Parks offered his own story to readers under the bold title “How It Feels to Be Black.” Broken into two parts, the first section consists of excerpts from his fictional autobiography, The Learning Tree. The second section—“The Long Search for Pride”—describes the blatant racism he experienced throughout his life and career.

Neighbors was printed with this section; its caption testifies to the spirit of the days leading up to King’s speech:

All our lives we have cloaked our feelings, bided our time, waited for the year, the month, the day and the hour when we could do without fear, at last, what we are doing just now.

|

Neighbors, Harlem, New York, 1952 |

~

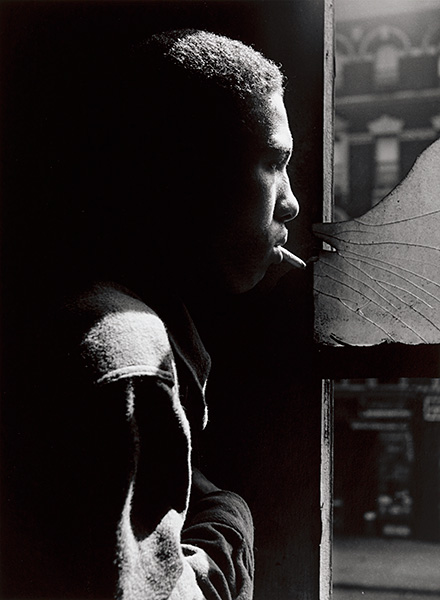

“Harlem Gang Leader,” Life, November 1, 1948

Red Jackson was the lead image in “Harlem Gang Leader,” Parks’s first major photo essay for Life in 1948. To shoot the story, Parks spent weeks following and developing a close bond with Leonard (Red) Jackson and other members of his gang. This sensitive image of Jackson and the unpublished portrait of his friend, posed on a bike in a quiet moment, convey the trust Parks was able to establish with these young men.

While Parks took hundreds of images that ranged from street fights to tender, domestic exchanges between Red and his mother, the majority of images the editors at Life selected focused on the violence. After the story appeared, Jackson said to Parks, “Damn, Mr. Parks, you made a criminal out of me.”

|

Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1948 |

|

Red Jackson, Harlem, New York, 1948 |

~

"The Restraints: Open and Hidden," Life, September 24, 1956

Beginning in September 1956, Life magazine ran a five-part series on segregation “designed to give useful perspective to the troubled events of today.” Through these essays, Life editors sought to explain the turmoil caused by the 1954 landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down the constitutionality of “separate but equal” public schools.

Parks took photographs for the fourth part of the series, which followed one family in Mobile, Alabama, across three generations. Although it was not included in the series, this photograph of Joanne Wilson and her niece standing beneath a “Colored Entrance” sign was part of that assignment.

I wasn’t going in. I didn’t want to take my niece through the back entrance. She smelled popcorn and wanted some. All I could think was where I could go to get her popcorn.

—Joanne Wilson, 2013

Wilson’s dilemma powerfully illustrates the challenge of navigating daily life and maintaining dignity under segregation. Some members of her family lost their jobs for participating in the Life essay and ultimately had to relocate. Yet they never regretted their decision and considered their role an act of resistance in the struggle for civil rights.

|

Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956 |

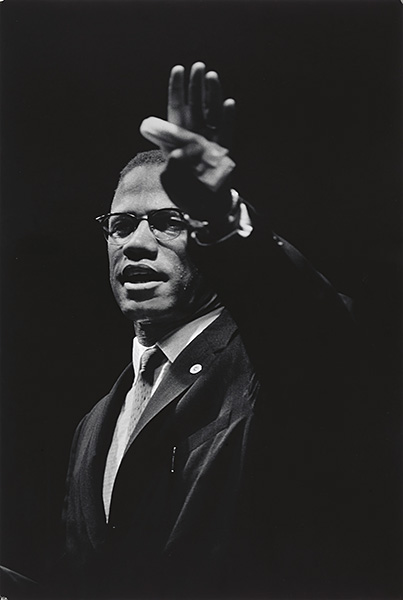

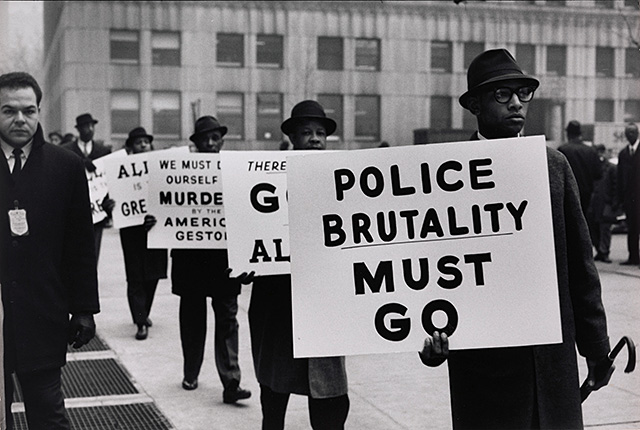

“Black Muslims,” Life, May 31, 1963

As part of an extensive assignment on the Nation of Islam, Parks lived within the organization for months and had unprecedented access to its leaders, Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X. When the photo essay was published, Parks’s nuanced and personal text, “What Their Cry Means to Me,” was included. Characteristically, Parks acknowledged what he thought were the organization’s shortcomings, but nonetheless used bold language to describe why Malcolm X’s message resonated so powerfully with many African Americans, especially in the North:

He is right. Because for all the civil rights laws and the absence of Jim Crow signs in the North, the black man is still living the last hired, first fired, ghetto existence of a second class citizen.

Parks also used the occasion to reflect on his own success and position at Life:

This same experience has taught me that there is nothing ignoble about a black man climbing from the troubled darkness on a white man’s ladder, providing he doesn’t forsake the others who, subsequently, must escape that same darkness.

This portrait of Malcolm X remains one of the most iconic images of that influential leader. The two untiled photographs that follow were not published in the final essay.

|

Malcolm X at Rally, Chicago, Illinois, 1963 |

|

Untitled, New York, New York, 1963 |

|

Untitled, New York, New York, 1963 |

~

“Stokely Carmichael,” Life, May 19, 1967

This picture of Stokely Carmichael was the lead image in the 1967 feature on the controversial African American leader, who coined the term “Black Power.” In 1966, as Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC), he advocated a shift away from the passive resistance tactics of civil rights activists like Martin Luther King Jr. and instead emphasized the need for self-defense. Parks wrote an essay that did not condone Carmichael’s militant tone, but nonetheless emphasized the racial and socioeconomic conditions that made Carmichael’s message resonate with America’s black youths.

|

Stokely Carmichael Gives Speech, Watts, California, 1967 |

Poignantly, Parks compared Carmichael’s willingness to risk his life to that of his own son, who was then serving in Vietnam:

In the face of death, which was so possible for the both of them, I think Stokely would surely be more certain of why he was about to die.

Contributor’s notes: Gordon Parks

Contributor’s notes: Sarah Eckhardt