print preview

print previewback ROSANNA OH

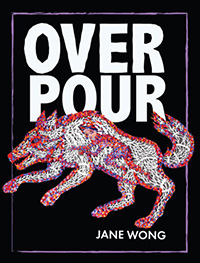

Review | Overpour by Jane Wong

Action Books, 2016

|

When ghosts appear in literature, as in The Odyssey and Asian folklore, they are understood to be on a journey, traveling between the lands of the living and the dead without fully inhabiting either, or to serve as bridges themselves, delivering messages. For Jane Wong, ghosts are muses that populate the poems in her arresting debut collection, Overpour. In her TEDx Talk, “Going Toward the Ghost,” Wong defines what she calls “a poetics of haunting,” which establishes the poet as an Orphic figure searching for the dead and their untold or lost narratives: “A poetics of haunting is not a matter of the repressed coming back to haunt you, but it is a productive and intentional act to go toward the ghost, and rewrite forgotten histories. It is a powerful way to reclaim our stories through language, both written and oral.” Death is a necessary condition in such poetry, and it can be a source of creative inspiration as generative as that of life. That ghosts reside in a liminal space between life and death, as well as past and present, provides an entry point for the poet—in Wong’s case—to reclaim and “rewrite forgotten histories.” What discoveries, then, does such an inquiry into the past yield? By seeking out the ghosts of the departed—which assume the forms of long-lost family and a nation’s history—Wong finds her point of departure.

One of the more important ghosts behind Overpour is Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, the Korean-American author of Dictee, whom Wong also acknowledges as a major influence in the same TEDx Talk. While Dictee is now canonized as a groundbreaking work of avant-garde literature, it was dismissed upon its publication in 1982 for its refusal to conform to what was then considered the mainstream Asian American aesthetic (as exemplified by poets like Garrett Hongo and Cathy Song), which valued linear storytelling with a hermeneutical purpose. Much of the book’s radical poetics arises from its fragmentation of English syntax and grammar, and the weaving together of multiple languages, disparate myths, as well as hagiography with autobiography and Korean history. Its success in conveying so much can be attributed to the complex framework of metaphors that sets the female body, an artist’s oeuvre, and her country in relation to one another. These ideas play out in Cha’s reaching out to the ghosts from Korea’s colonial past (especially freedom fighter Yu Guan Soon):

You leave you come back to the shell left empty all this time. To

claim to reclaim, the space. Into the mouth the wound the entry is

reverse and back each organ artery gland pace element, implanted,

housed skin upon skin, membrane, vessel, waters, dams, ducts,

canals, bridges.

Here, the human body is superimposed onto a literal map. “To claim [or] to reclaim, the space”—which is in this case a country—is achieved through language. Word-making and nation-building are one and the same.

Like Cha, Wong similarly relies on metaphors of language, country, and the human body to explore central themes of family history and collective trauma. Wong’s imagery, at once grotesque and vibrant, seems to take on flesh. In particular, the series “Ceremony” stands out, evoking a surrealist sensibility. From the first poem: “Terrible, the desert of our mouths, sweeping.” The fifth begins: “An architect folds a building inside of me. / The archways expand with each move.” Another series of images from “Elegy for the Selves”: “The eye of an eel / my father turns on a spit, / rolling in my mouth.” Wong offers beautiful Matryoshka doll after Matryoshka doll of images, as if to suggest that haunting is an infinite process of discovery.

Haunting is not only an act of the imagination—for it requires the ability to see entities beyond the present and reality—but also a visceral act of violence that scrutinizes everything and everyone with chilling methodicalness. In “And the Place was Matter,” the speaker describes a domestic tableau in which everyday life progresses as it should: “the highway expanded into four lanes / and the garlic blossomed in June.” And yet, rather than accept what she sees, the speaker instinctually questions it: “What is there left to recover?” The answer begins with the speaker’s own self-inquiry, which is often knifelike in its precision. She discovers her own capacity for violence in “No Need for the Moon to Shine in It”:

Some cells split despite death. When they opened

up the farmer, they found a grass clot in his lungs.

I come from a farming family. Which is to say,

I have killed plenty of things: spiders, ants, crabs –

leg by leg. Murder is to mitosis is to mercy.

We witness multiple acts of severing that range from the molecular to the abstract: mitosis, the farmer’s autopsy, and murder. Just as we see in Dictee, the line breaks here embody dismemberment and insert pauses that—despite the powerful images of violence—lend the poem an eerily detached quality. However, rupture and wounds here do not signify an absence so much as the opportunity to create. Mitosis, for example, is a cell’s simultaneous act of splitting and proliferation. Furthermore, by suggesting that her capacity for murder is a trait she inherits from her “farming family,” the speaker implies that violence can link generation with generation—it gives her an identity.

As a Chinese American poet, Wong seeks her ghosts in China. Going toward the ghost does not deny present reality, but rather forges transnational narratives. After her husband accidentally drives a car into a tree in “Thirty,” the vehicle spins out of control, becoming a time machine that transports the speaker “[a] country away,” where she can “hear oxen / snorting in milk-colored fog.” Wong inhabits a China that is not only rural, but also torn apart by a war she neglects to name. (She does, however, mention The Cultural Revolution elsewhere.) “Field Notes Toward War” begins with the observation, “The war is not over.” Such an omission reinforces the universal and cross-generational nature of war, as well as the hunger and death that accompany it.

If embracing one’s ghosts leads to never-ending tales of unspeakable suffering and trauma, what remains to be redeemed? Is it truly possible to know too much for one’s own good? Wong writes about empathy with such questions in mind, but arrives at no definitive or singular answer. In “Ceremony,” “[a] well fills with empathy, but no one falls in”; empathy is rejected even though the metaphor implies that it is a life-giving necessity. On the other hand, the ability to empathize sometimes overwhelms her. The poem “Debts” presents a moral tale in which empathy leads to guilt:

In the boredom of six o’clock

My brother plays with his loose tooth

On the news, someone shoots his brother by accident

If I could drape guilt over meGarlands of I’m sorry for pushing you down the stairs

Head to wall to head

I am reminded of Leslie Jamison, author of The Empathy Exams, who astutely observes, “Empathy means realizing no trauma has discrete edges”—in other words, it neither begins nor ends with a person. By giving the speaker a moral imagination, empathy becomes the mechanism by which she connects with those around her. Watching the news of a stranger shooting his brother provokes shame for pushing her own brother down the stairs. As in other poems, Wong here proves her gift for choosing details that concretize what she describes. “Head to wall to head” reads slowly, as though the memory were being replayed in slow motion, and it does so with such immediacy that it transcribes itself onto the reader’s own memory and conjures sounds to supplement the visuals it evokes. Memory, then, operates fluidly in a personal context and, by extension, as a form of record-keeping. As a witness, Wong suggests that Overpour itself is the result of a participatory relationship that involves the haunted and the ghost seeker.

The triumph of Overpour is the speaker’s commitment to haunting, in spite of potential suffering and devastation. In “Pastoral Power,” she calls her decision to “face” her grandfather’s ghost a “choice.” In “Twenty-Nine,” the speaker declares, “I’m that person who can’t stop / looking.” Wong’s allusion to Keats’s fragment, “This living hand, now warm and capable,” at the end of “Blood” further emphasizes her belief that her poems have a purpose that extends beyond her own family, country, and even lifetime. The ghostly image of the hand gesturing toward the reader is a request, one that Wong embraces by reclaiming her lost narratives. By offering her poems, Wong extends the same invitation to us. ![]()

Jane Wong is the author of the poetry collection Overpour (Action Books, 2016). Her poems have appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, North American Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. In 2016 she was awarded the Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize from The American Poetry Review.