print preview

print previewback EMILY BLOCK

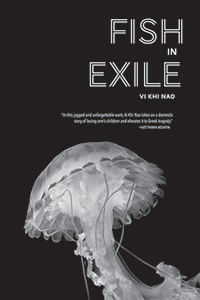

Review | Fish in Exile, by Vi Khi Nao

Coffee House Press, 2016

|

When the gods cried in Greek myth, their grief could split the world apart. After Eurydice descended to the House of Hades, Orpheus filled the earth with disconsolate music. Demeter blighted mortals’ harvests, creating winter, when Persephone first smoldered in the underworld. After Hyacinthus died, the bereft Apollo turned his dead lover’s body into a flower, forming the first hyacinth that split the ground (if not the world) open. Vi Khi Nao invokes all of these myths of loss in her lyrical, experimental debut novel, Fish in Exile—a narrative centered on a grieving couple, Ethos and Catholic, struggling to cope with the disappearance and presumed drownings of their two young children.

Following these deaths, husband and wife inhabit unsustainable, incompatible spheres of grief. Ethos disassociates, waxing poetic and constantly—self-pityingly—performing his anguish as if it were his new life’s work. Now that he’s left his job as a schoolteacher and lost his role as a father, Ethos carries a haversack around the house and talks in circles without ever arriving anywhere—a habit he illustrates when he asks his visiting mother, Charleen, a classics professor, “Is it better to be at home in exile or in exile at home?” He takes on the elaborate, impractical project of building an amusement-grade aquarium in the living room. Catholic, on the other hand, is decisive. She commits herself to her work, has a hysterectomy, and initiates and ends an affair with their neighbor, Callisto. In their distinct ways, the characters of Fish in Exile alternatively evade and confront questions of blame, abandonment, and exile.

Although many of these narrative details are not immediately clear to the reader, the instability Ethos and Catholic feel is evident from the start. Surreal images populate the landscape: we see, for example, with Persephone’s eye, a complex web of garlic roots suspended over hell, and twin coffins Ethos builds for the bodies of found jellyfish. Throughout the novel, object relations and conventional understandings of space collapse into the vast ocean that Ethos and Catholic return to, again and again, out of habit. Elliptical exchanges of dialogue cast doubt on already-unreliable narration. As in life, no one character’s view can be taken without at least a bit of skepticism.

Khi Nao shifts between different narrators and modes of focalization across the novel’s six sections, and discrete passages within those sections also vary in length and format. We see dialogue formatted as if in a play; characterizing, self-conscious footnotes; and even an interview transcript in a section titled “Callisto & Lidia.” For readers, this means that the narrators, and the implied author arranging these diverse textual elements, provide us with few sources of comfort, few easy toeholds in the narrative. Readers must navigate a world of loss—or, Ethos’s and Catholic’s separate but parallel spheres of loss—just as uneasily as the characters themselves. In a novel that resists a conventional shape, experiences of isolation, exile, and grief come to the reader in raw, relatively unmediated forms.

But the novel’s difficulties are pleasurable in a way Ethos’s and Catholic’s experiences of grief are not. Khi Nao doesn’t leave us completely adrift; we do have a chronological narrative structure—a structure the grieving parents, and Ethos in particular, cannot discern. Familiar allusions to the book of Genesis and to ancient Greek mythology, and the clarity of select borrowed forms (e.g., the play-formatted dialogue), also help ground readers, permitting us to move between discrete sections and points of view without losing our bearings.

As the characters in the novel grapple with their individual forms of exile and grief, one consistent function of the prose seems to be “to contemplate the gesture of blankness and to complete it if it hasn’t been fulfilled”—to contemplate especially the “disconnected and obscure and elliptical space between husband and wife.”

Opposing extremes consistently widen the chasm between Ethos and Catholic, or throw their disconnect into sharp relief. Khi Nao invokes motifs of light and darkness, in literal and figurative forms: the corporeal and the ethereal, as in the menstrual stains that distract Ethos from his waking dreams; survival and annihilation, the two alternatives tragedy presents; and perhaps most poignantly, “the literal world and the conceptual world,” which appear in the novel to be painfully indistinct, hopelessly intertwined. These extremes are obstacles for Ethos and Catholic to overcome—vehicles through which they enact, perform, and prolong their separate emotional exiles. Ethos’s and Catholic’s responses to these variable forces provide a key source of tension in the book. In some sense, the central conflict is that Ethos is always turning toward something—toward his grief, toward his wife, toward the light or “the gesture of blankness” that his own darkness seems to blot out—and Catholic is always turning, literally and figuratively, away.

Of this divide, Ethos writes:

Everything is impossible. [Catholic’s] love for me, if there is any left, is impossible. . . . When the twins were here, time alone was so rare. Any moment alone was diamonds, pure glacier. Unable to bear myself in her presence, I remove myself from her hemisphere. I lean back into the coffee table and raise myself up with my hands. . . . In one quick and mechanical motion, I exit the diagram of her body. The diagram of the living room. With all their narratives and the empty lines and shadows and incomplete voices. I don’t know if I can bend for them anymore.

The dissociation we see in this passage, where Ethos’s “myself” becomes an object he can act upon, is quite characteristic of the novel. The divide between the “real” and the “imagined,” the world outside the characters and within, is constantly shifting and often purposefully blurred. Catholic really does sew dresses for fish (the easier to wrangle them during walks), which isn’t much closer to realism than a scene Ethos merely imagines, standing in the kitchen and claiming to feed from the moon: “I shovel light urgently into my mouth,” he writes. That dreamlike quality creates the novel’s primary source of hermeneutic suspense: these details function like a puzzle, leaving the reader to wonder how all of the surreal individual pieces fit together and make meaning.

It’s tempting to chalk Fish in Exile’s strangeness up entirely to the grief and guilt that plague the central characters: Ethos and Catholic have experienced devastating losses; their perceptions of reality are therefore distorted, reflective of two puzzling, befogged inner worlds.

Still, to suggest that the strangeness of Fish in Exile reflects no more than a marriage of form and content (i.e., experiences of grief relayed in off-kilter, grief-stricken language) is to reduce the complexity of the novel and to ignore much of the craft behind it. Although grief is the impetus for Catholic and Ethos’s isolation, Khi Nao’s experiments with form and arrangement operate under a poetic logic similar to that of the central grieving characters—and we have no reason to attribute the same grief to the implied author as we do to her characters. Like Ethos and Catholic, the implied author who employs this logic, and peripheral characters Charleen and Callisto, seems to be reckoning on one level or another with the titular concept of exile: How to communicate the incommunicable? How to escape isolation? How to find a language? Khi Nao’s novel may, in fact, best be described as an attempt to find that language. She has shaped every sentence with Demeter’s ancient, inborn “syntax of pain,” introduced in the prefatory poem, “Demeter by the Slanted.” In this way, Khi Nao offers us a compelling illustration of inherited trauma that language conventionally resists.

This attempt to find a language is clear enough in Callisto’s insistence that Catholic respond to his letters, and likewise in the self-conscious, unanswerable missives Ethos writes to the outside world—poem-like notes addressed to Ithaca and Moscow. As readers, we eventually realize the titular “fish,” which seems initially to apply only to Ethos, is in fact the plural form of “fish,” and it applies to almost all the characters in the novel—if I may permit myself the pun, to almost all the fish in the sea. For Ethos and Catholic, grief and exile are synonymous. But it seems to me it’s not so much Ethos and Catholic’s grief as it is the implied author’s search for a language of exile—for a narrative, a metaphor, a body of images that give shape to otherwise formless, free-floating experiences of isolation—that informs the novel’s experimental style.

The most central and compelling philosophical concern of Fish in Exile, then, might be best described in this meditation from Ethos: “Can freedom exist for a fish? Was [my pet fish]’s freedom incarcerated before she met Catholic and me because she had the entire sea to roam then?” How different, really, is an excess of freedom from exile? Freedom, Khi Nao’s characters suggest, is an illusion, but loss and abandonment are true—and to experience loss, or to be abandoned, is to live in exile.

In this luminous first novel, Vi Khi Nao proposes that exile takes many forms, distorting reality, or exposing the already-present fractures in everyday life. She suggests further that even in the face of such brokenness, light seeps in: implausibly, and through unimaginable darkness, flowers cut through earth all the time. On the other side of destruction, Khi Nao suggests we may find a place for rebirth. ![]()

Vi Khi Nao is the author of the novel Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), the short story collection A Brief History of Torture (Fiction Collective 2, 2017), and the poetry collection The Old Philosopher (Nightboat Books, 2016), which won the 2014 Nightboat Poetry Prize.