print preview

print previewback VICTORIA C. FLANAGAN

Review | Look, by Solmaz Sharif

Graywolf Press, 2016

|

So often, we speak of literature in terms of light: a novel might be illuminating, an essay enlightening; a collection of poetry might be lauded for its singular, driving voice—its spotlighting effect. This impulse, surely, reflects literature’s power to show, to evidence, convince, and impart. Describing a literary success would thus require a nod toward a work’s revelatory achievement. But Solmaz Sharif’s debut collection, Look, defies this light-driven impulse almost totally. Instead, her distilled and remarkably clear-eyed debut challenges readers’ basest perceptions of that which needs to be illuminated. By presenting the unacknowledged historical, cultural, personal, and linguistic consequences of war as textural, as lived, and as undeniable fact, Look begs a linguistically driven, indicting frameshift—more a total recontextualization than an amendment of view.

Lifting its characterizing language directly from the United States Department of Defense’s Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, Sharif’s collection indicts the complicit nature of history, how violence—both embedded and inserted—in our language demands a human consequence. The lifted terms—denoted by small caps—range from surprisingly innocuous, as in the titular “LOOK”:

Whereas years after they LOOK down from their jets

and declare my mother’s Abadan block PROBABLY

DESTROYED, we walked by the villas, the faces

of buildings torn off into dioramas, and recorded it

on a handheld camcorder;

to overtly euphemistic, as in “Dear INTELLIGENCE JOURNAL,”:

Lovely dinner party. Darling CASUALTIES and lean

sirloin DAMAGE of the COLLATERAL sort.

Extended my LETTER OF OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE

to the DESIRED INTERNAL AUDIENCE, reaching

DESIRED EFFECT and DESIRED PERCEPTION . . .

On first encounter, the typographic distinction sirens a frightening truth—the barrier between the language of war and language of the everyday is, at best, highly permeable, at worst nonexistent. By the time readers encounter poems like “SAFE HOUSE”—in which each line begins with militaristic terms like SANCTUARY, SANITIZE, SCALE, SEARCH, SECRET and SECTOR—any distinction between everyday language and the terms of war has dissolved. This is what Look, as a whole, neatly proves: that violence—as an indivisible and unconscious component of American experience—is so pervasive, we don’t even register war’s impact on our own language.

With undeniable force, Sharif’s unadorned writing crosshatches militaristic language with recorded and lived experience, and the poems serve as both a proving ground and reckoning. In poems like “PERSONAL EFFECTS,” her avowal is clear: “Daily I sit / with the language / they’ve made // of our language,” and so the reader (as a reader reading) is immediately complicit, confronted. As the collection’s title suggests, Look refuses to turn away, refuses to gloss over historical or personal fact, and crucially denies readers the privilege of looking away too. In a sense, the title functions as both an invitation and a command, and this ambiguity is essential. The inherent violence of language here is doubled—the speaker of these poems is complicit, too, because she is also bound by this language, despite variable context. No one gets an out. Language, within Look, is thus a vital paradox, a necessary complexity, and an expression of self-consciousness marked by the subjectivities of nationality, heritage, and disparate cultural valuations. “Now, therefore, // Let it matter what we call a thing,” Sharif writes. “Let me LOOK at you.”

Because Sharif locates herself within American experience—because she indicts herself as a user of this language—readers suffer this linguistic tension just as powerfully as we observe it. “According to most / definitions, I have never / been at war,” she writes. “According to mine, / most of my life / spent there. . . .” Because we’re shown our speaker as a teenager, defiant and specifically complicit in the violence and erasure Look condemns, we understand her approach as nuanced and particularly self-conscious:

the army-issued belt

I would wear with Dickies

the army jacket

the Doc Martens

the military gear

that would stomp through my father’s home

take that poster down my father said

it was Saddam in crosshairs

In these moments of vulnerability and self-criticism, Sharif earns her direct indictments, should readers have lingering doubts: “America, // you have found the dimensions / small enough to break / a man.” It’s a reminder that Sharif herself approaches this language from a post-war perspective, having acquired it much the same way as her audience. The difference in Sharif's engagement with terms like DEAD SPACE or PERMANENT ECHO is one of scope, one of effect, and one of informed consciousness—she’s exploring and exploiting the context of a language that actively works against her.

As a poet born to an Iranian family and struck by the losses—both personally suffered and broadly observed—of the Iran-Iraq War, Sharif’s poems often boast a documentary impulse. Her detail-driven ruminations humanize that which has been actively dehumanized, and the persons that populate Look are never given over or described in simple biological terms. Their bodies are not bodies, despite what a military dictionary might say. Instead, these are brothers, fathers, daughters, friends, uncles, wives. The emblematic minutia of daily life is celebrated as emblematic because the emblematized catalog means life, means existence, and stands as a sort of protest:

Suitcases of dried limes, dried figs, pomegranate paste,

parsley laid in the sun, burnt honey, sugar cubes hardened

on a baking sheet. Suitcases of practical underwear,

hand-washed, dried on a door handle, stuffed into boxes

from Bazaar-e Vakeel, making use of the smallest spaces,

an Arcoroc tea glass. One carries laminated prayers

for safe travel. . . .

War, Sharif insists, is not a disembodied force, just as the language of war is not its own language. When military jargon bumps up against personal narrative, memory, inheritance, and the echo of violence across continents, these details ring out.

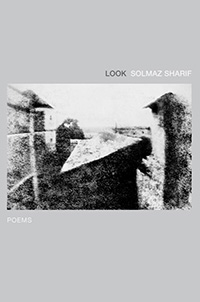

In celebration of this intentional observation and visibility, the book’s cover—Niépce’s famous camera obscura photograph overlooking Saint-Loup-De-Varennes—serves as a reminder that observance is necessary for memory. We understand the import of Sharif’s humanizing details, that they signify a shift in focus, a shift in our understanding of both personal and cultural realities. If we take Barthes’ notions of photography to be transferrable to poetry, Look provides a sequence of puncta against a backdrop that otherwise breeds indifference. These people, these landscapes, stick with us; our thinking about language must change. The late uncle who haunts the pages of Sharif’s collection is not just another fallen soldier, and we cannot see him as such. Once we’ve seen the photo of the beloved uncle, when the thermal image of a hunted body is a specific human—a non-object—when “the faces of buildings torn off into dioramas” is no longer an abstraction but an event of immediate, personal consequence, Look proves as unremitting as the war that incites it, that necessitates a book like this.

Dominating the third of Sharif’s four sections, “PERSONAL EFFECTS”;—Sharif’s most pointed rumination on her uncle’s death in the Iran-Iraq War—serves as the culmination of Look’s public, linguistic, and personal critiques. With characteristic precision, Sharif exemplifies her own understanding of and engagement with violence and grief, and her investment is made plain. Throughout the second and third sections especially, readers come to understand that, for Sharif, the de-euphemizing of language is a necessity; these consequences are consequences she herself bears. Contextual, meditative, and intensely personal, these middle sections reflect a different sensibility, connecting the larger linguistic critique to real-world, personal consequence. In this way, these sections prove the theses that “LOOK” ; and “DRONE”—the single-poem pillars of the first and fourth sections—put forth, and they function as markedly human evidence of perpetual, ruinous violence. But it’s important, too, to stress that Sharif begins and ends with a keen eye trained on the project-inciting military terms. The first and final sections of Look bear the weight of militaristic language largely without context, and these laser-focused poems remind us that, for Sharif, things begin and end with the violence rooted in the very language we use.

As the formally disparate poems of Look coalesce, the cost of this specifically violent language is undeniable: “that we need words // for refusal makes it likely / we would refuse things / of each other.” Each poem—be it a list, erasure, or part of a longer sequence—provides another point of evidence; each poem lays a crucial stone of her succinct, clear-eyed argument. Just as the consequences of violence and of language have compounded over time, Sharif’s poems act as a kind of erosion, a lyric attrition. We are heartbroken by a line in “DRONE”—“I wrote their epitaphs in chalk”—because we know, for Sharif, “their” means “uncle,” means a boy in a red jacket, means neighbors, brothers, friends. And for all its striking moments, this is Look’s principal accomplishment—that it establishes a driving, critical rhetoric and a compelling, empathic narrative in defiance of a language set up to deny that rhetoric, to deny that narrative. We rarely encounter collections that so clearly and cleanly articulate an idea, but Look certainly does, and all with the immense burden of a language stacked against the collection’s very existence.

Sharif’s poems deftly recontextualize militaristic terms in a manner that indicts the politics and violence which gave rise to this language, and she forces us to reconsider our unconsidered use of this language as an act of complicity. But, given the quiet power of Look, it’s easy to forget that the collection never seeks to redefine. By forcing her readers to confront the personal effects of war, Sharif proves that the way to de-euphemize language is not to strip language of its power. Instead, Look reminds us that language’s power is rooted in that characteristic of language which precedes an overt politicization: its malleability. If a language can absorb the violence of war, then it can also reject the violence of war. By recontextualizing and reclaiming these militaristic terms, Look proves that the power of language swings both ways. As the closing lines of the collection illustrate, war has already marked this violent lexicon. Speaking of it, speaking against it, is what remains: “we have learned to sing a child calm in a bomb shelter / : I am singing to her still.”

Perhaps this is why, by the end of the collection, what might once have seemed Sharif’s titular invitation rests solidly on the side of command. Look does not give an option to look, just as it does not uphold a separating pane of persona or historical perspective. Rather, the text refuses to frame, block out, or contain the experience of lived and inherited violence. In Look, Sharif has proven that violence is as contemporaneous and pervasive as language itself, and it’s impossible to come away from this stunning debut without a reformed mindfulness for the burden and import of our language. ![]()

Solmaz Sharif is the author of the poetry collection Look (Graywolf Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the National Book Award, received the 2017 PEN Center Literary Award for Poetry, and received the 2018 Levis Prize. She is a lecturer at Stanford University.