print preview

print previewback 1917 SUITE | SILENT SENTINELS AND THE NIGHT OF TERROR

VOICES FROM OCCOQUAN

Dorothy Day at Occoquan: From this Wound, this Ugly Knowledge

by Katherine Mooney Brooks, Blackbird Associate Editor

In her 1952 text The Long Loneliness, Dorothy Day provides a uniquely thorough account of her time at Occoquan Workhouse. Perhaps due to the way time works upon the mind, Day provides far more details than many of the statements made by other imprisoned suffragists, and far more introspection on the effects of imprisonment, the hunger strike, and bearing witness to the brutality and injustices faced by suffragists in Occoquan.

Prior to her arrest, Dorothy Day had been working at The Masses as an assistant to the assistant editor, Floyd Dell, who wrote of her in his autobiography, Homecoming, in 1933:

For a while my assistant on The Masses was Dorothy Day, an awkward and charming young enthusiast, with beautiful slanting eyes, who had been a reporter and subsequently was one of the militant suffragists who were imprisoned in Washington and went on a successful hunger strike to get themselves accorded the rights of political prisoners. . . .

|

|

| Dorothy Day, c. 1916. | |

Picketing

Day describes traveling to Washington following her tenure at The Masses, which had only just been suppressed by the Espionage Act of 1917, claiming that the publication of material undermining or in any way offending the war effort would be a federal offense.

Day traveled to Washington with a friend named Peggy Baird, a painter for whom Day had supposedly posed. Once there, they picketed the White House with other organizers. In The Long Loneliness she writes:

The women’s party who had been picketing and serving jail sentences had been given very brutal treatment, and a committee to uphold the rights of the political prisoners had been formed.

Hypolite Havel, who had been in so many jails in Europe, described to us the rights of political prisoners which he insisted had been upheld by the Czar himself in despotic Russia: the right to receive mail, books and visitors, to wear one’s own clothes, to purchase extra food if needed, to see one’s lawyer. The suffragists in Washington had been treated as ordinary prisoners, deprived of their own clothing, put in shops to work, and starved on the meager food of the prison. The group who left New York that night were prepared to go on a hunger strike to protest the treatment of the score or more women still in prison.

It would seem as though the women attending the picketing on this occasion were keenly aware of the likelihood of arrests and imprisonment, and stood, again, as silent sentinels in support of their members already incarcerated. We note Day’s awareness of the rights of political prisoners, as the treatment she ultimately received at Occoquan was markedly different than even the treatment of political prisoners in Russia at the time.

Arrest

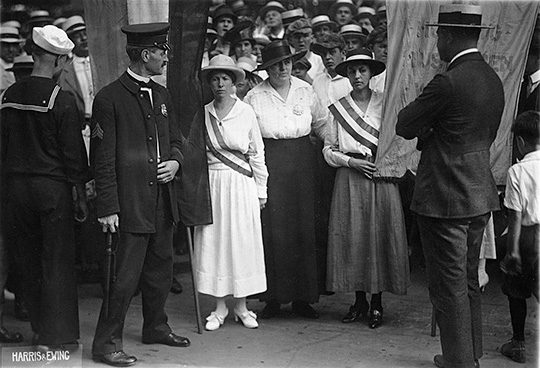

Dorothy Day describes the scene on the day of her arrest as especially chaotic. Spectators amassed in the park across the street from the White House; police and press waited to meet the pickets as they organized for the day in purple and gold ribbons, marching two by two with banners held high.

There was a religious flavor about the silent proceedings. To get to the White House gates one had to walk halfway around the park. There were some cheers from women and indignation from men, who wanted to know if the President did not have enough to bother him, and in wartime too! By the time the third contingent of six women reached the gates—I was of this group—small boys were beginning to throw stones, and groups of soldiers and sailors appearing from the crowd were trying to wrest the banners from the hands of the women. The police arrived at once with a number of patrol wagons. I had to struggle for my banner too, with a red–faced young sailor, before a policeman took me by the arm and escorted me to the waiting police van. Our banners were carried, protruding from the back of the car, and we made a gay procession through the streets.

|

|

| Arrest of Catherine Flanagan of Hartford, Connecticut (left) and Madeleine Watson of Chicago, Illinois (right) at the White House East Gate. At the left, a sailor taunts them as they are bookended by policemen, a policewoman between them, August 1917. | |

For the women, the events following the arrest were unusual in that their social influence meant little to nothing. The National Woman’s Party Headquarters had posted bail for all of the arrested suffragists, and having given their contact information for public record, they were released with the promise to attend trial at ten the following morning. At trial they were promptly found guilty and sentencing was postponed to a later date.

The pickets wasted no time in taking up new banners and donning again their purple and gold ribbons before arriving at the White House. The methods of the police were predictable: the women were again arrested and bailed out. Once more they were tried in court and received postponed sentences. This cycle had begun to occur more and more often as the Wilson administration watched the women march right back to the White House gates, undeterred.

On Dorothy Day’s third arrest, the women were taken to Central Station, where they refused to post bail. This time was different. The women spent the night in the House of Detention, which was ill equipped for such a numerous amount of prisoners. The women were imprisoned with fifteen women assigned to each room, originally meant for two people.

The following morning the thirty–five women were presented in front of the judge, and took every opportunity to advocate for both the enfranchisement of women and for better treatment for political prisoners.

Dorothy Day then recalls Lucy Burns receiving a lengthier sentence of six months, as she had been the appointed leader of the group. She recalls older women—such as Mrs. Mary Nolan, whose account can be found on the “Administrative Terrorism” page of our “Voices from Occoquan: Paper Scraps and Affidavits” menu in this suite—receiving shorter sentences closer to fifteen days. The rest of the women generally received the sentence of thirty days.

Day writes:

We started our hunger strike right after receiving our sentences. The scant meal of weak coffee, oatmeal and bread was the last one we expected to have until our demands (for the rights of political prisoners) were granted or we were released. I was too excited to worry much about food. I was to find that one of the uglinesses of jail life was its undertone of suppressed excitement and suspense. It was an ugly and a fearful suspense, not one of normal hope and expectation.

For many hours the women had to wait in a little room back of the court. This waiting, too, was part of the burden put upon us. Years later when I read Arthur Koestler’s Scum of the Earth, he too spoke of the interminable hours of waiting experienced by prisoners who were being sent to a concentration camp.

Finally, at four o’clock, things began to happen to us. Prison wagons were brought, wagons that had only ventilators along the top and were otherwise closed. Two of them sufficed to carry the prisoners to the jail. When they reached that barren institution on the outskirts of the city, backed by a cemetery and surrounded by dreary bare fields, there was another long halt in the proceedings.

For many of its years of operation, Occoquan Workhouse ran a train to and from its premises. From the police vans the women were led to a train, which waited with the specific purpose of transporting the women to the workhouse. It was a dark ride, Day notes, as the streetlamps were not yet lit.

The mood in the train was tense. Day writes:

Those women who had served sentences before knew that we were being taken to the workhouse, and many stories had been told of what the prisoners had suffered at the hands of the violent keeper there, a man named Whittaker. We were all afraid.

Day watched the dimming landscape from her seat by the window. The sunset was “sadly beautiful.” Still, she found the presence of her friend Peggy Baird comforting, and they resolved to remain as close as possible to one another as their fate unfurled.

Occoquan

The women were exhausted by the time they arrived at the workhouse, and the arrival proved to be no relief at all. The women were made to wait as their spokesperson demanded to meet with Superintendent Whittaker, the man of whom so much had been said. The request was refused.

The women waited wearily for some time. The younger members of the group arranged themselves on the floor, while older women found chairs and benches to rest upon.

“It was not until ten o’clock,” Day writes, that Mr. Whittaker, “a large stout man with white hair and a red face, came storming into the room, leaving the door open on the porch, from which came the sound of the shuffling feet of many men.”

Whittaker was well known for his rough demeanor and his impatience. He was more prepared for some reckless militia than for the group of educated women who awaited his arrival.

Terror

When the spokesperson who had initially asked to speak with Whittaker stood and began to announce that the women would begin their hunger strike if their demands were not met, Whittaker turned and made a gesture from the doorway.

Immediately the room was filled with men. There were two guards to every woman, and each of us was seized roughly by the arms and dragged out of the room. It seems impossible to believe, but we were not allowed to walk, were all but lifted from the floor, in the effort the men made to drag, rather than lead us to our place of confinement for the night.

The leaders were taken first. In my effort to get near Peggy I started to cross the room to join her, and was immediately seized by two guards. My instinctive impulse was to pull myself loose, to resist such handling, which only caused the men to tighten their hold on me, even to twist my arms painfully. I have no doubt but that I struggled every step of the way from the administration building to the cell block where we were being taken. It was a struggle to walk by myself, to wrest myself loose from the torture of those rough hands. We were then hurled onto some benches and when I tried to pick myself up and again join Peggy in my blind desire to be near a friend, I was thrown to the floor. When another prisoner tried to come to my rescue, we found ourselves in the midst of a milling crowd of guards being pummeled and pushed and kicked and dragged, so that we were scarcely conscious, in the shock of what was taking place.

The account of what they termed a riot was printed in the New York Times later, and the story made the event much worse than it was, though it was bad enough. I found myself flung into a cell with one of the leaders, Lucy Byrnes, a tall red-haired schoolteacher from Brooklyn, with a calm, beautiful face.

It is fascinating that, even as she recalls the unorthodox and uncalled for treatment by the guards, Day maintains that the New York Times article—which we have republished here and can be found on the introductory page to this suite—had dramatized the situation.

While the treatment could, of course, have been far more threatening to the women than it was, the violence they experienced upon their arrival at Occoquan was horrific. All that the women had requested was an empathetic audience, an ear to receive their request for the right to vote, a right white men had been exercising since the establishment of this country’s constitution. The women had not presented a threat to anyone beyond those who wished to exclude them from the political arena.

Dorothy Day assessed her surroundings. In a cell with Lucy Burns, she recalls:

She was handcuffed to the bars of the cell, and left that way for hours. Every time she called out to the other women who had been placed up and down a corridor in a block of what we found out afterward were punishment cells, Whittaker came cursing outside the bars, threatening her with a straitjacket, a gag, everything but the whipping post and bloodhounds which we had heard were part of the setup at Occoquan.

An hour or so later, when things had quieted down, an old guard shuffled down the corridor and unlocked the handcuffs from the bars of the cell but left them on her wrist so that she had to sleep with them on. Each cell was made for one prisoner, so there was only a single bunk, a slab of wood in the corner. There were two blankets on it, and when I had unfastened her shoes and arranged the blankets, Lucy and I tried to make ourselves comfortable on the single slab. In spite of our exhaustion, we could not sleep, but lay there talking of Conrad’s novels for some time. Early the next morning Lucy was taken away to what we afterward heard was a padded cell for delirium tremens patients and I was left alone to try to sleep a good part of that first sad day.

There were no meals to break the monotony, and if the women tried to call out to one another, there were always guards on hand to silence them harshly. In the morning we were taken one by one to a washroom at the end of the hall. There was a toilet in each cell, open, and paper and flushing were supplied by the guard. It was as though one were in a zoo with the open bars leading into the corridor. There were only narrow ventilators at the top of the rear wall of the cell, which was a square stone room. The sun shone dimly through these slits for a time and then disappeared for the rest of the day. There was no way to tell what time it was. In the darkness of the night before we had not noticed a straw mattress in another corner of the cell. I put this on the built-in bunk. The place was inadequately heated by one pipe which ran along a wall. Suspense and fear kept one cold.

Hunger

Milk and toast were brought twice the next day, left untouched by the prisoners. Day describes how tempting the food had been that first day, how appealing the toast was.

It was an unsettling experience. The women guessed at how many of them had ended up in punishment cells and where the others might have been held, the thought of bloodhounds and whipping posts some far-off possibility, a lurking threat. Time weighed heavily upon the suffragists, unable to communicate with each other, though they did try, as Day remembers:

Every now and then the women called out to each other. We had neither pencil nor paper so we could not write; no books, so we could not read. I found a nail file which I began to automatically use on my nails, and as though I had been spied on, a guard immediately came in and took it from me. . . .

“Keep the strike,” one of the girls called out once. “Remember, if it’s broken we go back to worms in the oatmeal, and the workshop.”

For Day, the hunger strike was worse than labor and the heavy, uncomfortable prison clothes. She describes the six days of fasting, languid in her cell without intellectual stimulation or distraction as feeling as though they lasted “six thousand years.”

The women were nauseous and lightheaded, yet they remained committed to their cause. Unable to comfort one another or communicate in any verbal sense, they retreated to their own thoughts. Their minds, at least, were liberated.

Day writes:

To lie there through the long day, to feel the nausea and emptiness of hunger, the dazedness at the beginning and the feverish mental activity that came after.

I lost all consciousness of any cause. I had no sense of being a radical, making protest against a government, carrying on a nonviolent revolution. I could only feel darkness and desolation all around me. The bar of gold which the sun left on the ceiling every morning for a short hour taunted me; and late in the afternoon when the cells were dim and the lights in the corridor were not yet lit, a heartbreaking conviction of the ugliness, the futility of life came over me so that I could not weep but only lie there in blank misery.

I lost all feeling of my own identity. I reflected on the desolation of poverty, of destitution, of sickness and sin. That I would be free after thirty days meant nothing to me. I would never be free again, never free when I knew that behind bars all over the world there were women and men, young girls and boys, suffering constraint, punishment, isolation and hardship for crimes of which all of us were guilty.

It is Dorothy Day’s account that seems to stand in such stark contrast to those of the other women arrested on that occasion. Day recalls in great detail the depth of her emotional trauma in that isolated cell at Occoquan. While so many others speak of the hardship of the struggle for suffrage, it is Day alone who so freely confesses to losing that sense of pride and righteousness. She struggled with the hunger strike, as each day guards left milk and toast in her cell, and still she never buckled under her fear, her physical discomfort.

Meditation

Alone with her thoughts, she reflected on the human condition in its entirety. She seems, at times, to recognize her own privilege against so many others who suffer daily, who suffer for their entire lives with no relief. In these moments she appears to lose some sense of innocence—through her own imprisonment she gains an acute insight into what it means to face injustice. She resolves herself, even in her own despair, to remember this feeling of empathy for the hardships of others.

She writes:

The mother who had murdered her child, the drug addict—who were the mad and who the sane? Why were prostitutes prosecuted in some cases and in others respected and fawned on? People sold themselves for jobs, for the pay check, and if they only received a high enough price, they were honored. If their cheating, their theft, their lie, were of colossal proportions, if it were successful, they met with praise, not blame. Why were some caught, not others? Why were some termed criminals and others good businessmen? What was right and wrong? What was good and evil? I lay there in utter confusion and misery.

When I first wrote of these experiences I wrote even more strongly of my identification with those around me. I was that mother whose child had been raped and slain. I was the mother who had borne the monster who had done it. I was even that monster, feeling in my own breast every abomination. Is this exaggeration? There are not so many of us who have lain for six days and nights in darkness, cold and hunger, pondering in our heart the world and our part in it. If you live in great cities, if you are in constant contact with sin and suffering, if the daily papers print nothing but Greek tragedies, if you see on all sides people trying to find relief from the drab boredom of their job and family life, in sex and alcohol, then you become inured to the evil of the day, and it is rarely that such a realization of the horror of sin and human hate can come to you.

Dorothy Day reflects upon this experience so many years after it was endured, and still manages to recover her own old thoughts, the gravity of the realization that imposed itself upon her. Even in November of 1917 she knew the experience would mark her forever:

Never would I recover from this wound, this ugly knowledge I had gained of what men were capable in their treatment of each other. It was one thing to be writing about these things, to have the theoretical knowledge of sweatshops and injustice and hunger, but it was quite another to experience it in one’s own flesh. There were those stories too of a whipping post and of bloodhounds wandering through the grounds to terrorize the prisoners. These things had been sworn to by a former matron of the workhouse, and the superintendent did not deny them.

I had no sense as I lay there of the efficacy of what I was doing. I had instead a bitter awareness of the need of self-preservation, the need to escape, the need to endure somehow through the days of my imprisonment. I had an ugly sense of the futility of human effort, man’s helpless misery, the triumph of might. Man’s dignity was but a word and a lie. Evil triumphed. I was a petty creature, filled with self-deception, self-importance, unreal, false, and so, rightly scorned and punished.

All she could do was wait and continue to bear the burden of the movement. Time passed slowly as she watched that bar of sunlight dim as the days wore on. She recalls the sound of pigs outside and the sparrow that nested just beyond her window, the sound of feet in the hallway, all the more terrifying when they quickened. The footsteps were little comfort for her; they filled her with foreboding anxiety.

She fell into lapses of nightmares in the middle of the night, one about a play in which she was surrounded by an audience of children, masked actors, and a little boy falling from the balcony.

Faith

On the fourth day of her imprisonment she received the Bible she had requested days earlier. Reading it alleviated her anxieties. She was comforted by her memories of childhood faith, by the words of psalms she had nearly forgotten. She was grateful. She remembers:

Then shall they say among the Gentiles: The Lord hath done great things for them. The Lord hath done great things for us: we are become joyful. Turn again our captivity, O Lord, as a stream in the south. They that sow in tears shall reap in joy. Going, they went and wept, casting their seeds. But coming, they shall come with joyfulness, carrying their sheaves.

Day did not fail to grasp the implications of the words she read. So much of it talked of survival and endurance, faith that is tested again and again and never folds. Every hour of daylight in her cell, she sat with the book open in front of her.

I clung to the words of comfort in the Bible and as long as the light held out, I read and pondered. Yet all the while I read, my pride was fighting on. I did not want to go to God in defeat and sorrow. I did not want to depend on Him. I was like the child that wants to walk by itself, I kept brushing away the hand that held me up. I tried to persuade myself that I was reading for literary enjoyment. But the words kept echoing in my heart. I prayed and did not know that I prayed.

Something in Dorothy Day seemed to change. She was no longer so fearful of the futility of her effort. She was strengthened by her faith in God, which, in turn, strengthened her sense of devotion toward the cause of defending democracy, improving human conditions for all people. She writes:

If we had faith in what we were doing, making our protest against brutality and injustice, then we were indeed casting our seeds, and there was the promise of the harvest to come.

Progress

On the sixth day of the hunger strike, the women were moved to hospital cells, a vast improvement from the punishment cells with which they had grown so familiar. The new cells were warm and well lit. It was there that Dorothy Day was reunited with her friend Peggy Baird. The two were separated by a wooden partition through which they would pass small notes, “written on toilet paper with a stub of pencil which Peggy somehow managed to keep when everything else was taken from us.”

Despite the comfort of being so close to Baird after all that they had been through, the hospital cells did not completely shield them from the reality of their imprisonment.

Day writes:

On the other side one of the older women lay in silence all through the day. Twice a day orderlies came to the room. Holding her down on the bed, they forced tubes down her throat or nose and gave her egg and milk. It was unutterably horrible to hear her struggles, and the rest of us lay there in our cubicles tense with fear.

Dorothy Day was not one of the many women who received forced nutrition during their stay at Occoquan, but she was not untouched by it. The woman on the other side of Day’s room is never named, but her experience was not uncommon. So many suffragists on hunger strikes in the workhouse and neighboring prisons were force-fed by guards and matrons, and with little delicacy. Alice Paul, away in the psychopathic ward of Washington, D.C.’s District Jail at this time, was said to have been force-fed three times a day for at least ten days.

Finally, Peggy Baird and Dorothy Day broke their fast on the eighth day of their imprisonment. Day recalls:

Peggy weakened on the eighth day, and took the milk toast which was brought in to us still. She urged me to keep her company, and I refused. “Don’t be such a fool,” she whispered through the aperture by the radiator. “Take this crust then and suck on it. It’s better than nothing.”

I accepted this compromise, and she carefully tore off the crust of the bread and stretched it out to me. I was just able, thanks to her long fingers and my own, to reach it and draw it in. With what intense sensual enjoyment I lay there in my cot, taking that crust crumb by crumb. I did not feel guilty for breaking the strike in this way after eight days. All but two or three of the suffragists were holding fast and worrying the State Department, the President, the great newspaper public, besides the jail authorities. I upheld Peggy, my friend, by sharing her crust, for which I was deeply grateful, and I continued the protest we had undertaken. Cheating the prison authorities was quite in order, I reasoned.

The strike officially broke on the tenth day. The suffragists received an announcement that their demands to be treated as political prisoners would finally be met. All of their struggle had finally been rewarded.

The women were transferred to City Jail. Their clothing and mail were returned, and they were given the freedom to walk about the halls. They ate the milk toast, and other meals.

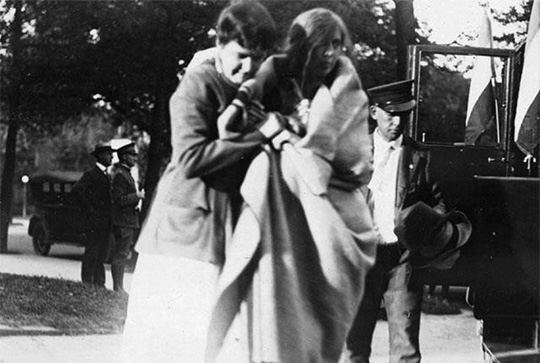

Day recalls their departure from Occoquan:

Within a few days we were taken in limousines into Washington. The air was invigorating, with the smell of snow; the woods still glowed in spots and the sun was warm.

|

|

| Kate Heffelfinger released from Occoquan, 1917. | |

In the Washington jail we chose our own cells and Peggy and I chose one on the top tier furthest from the matron’s prying eyes. There was more air there, too. The high windows that stretched from the first to the third tier were kept open at the top by the request of the women, a request granted after previous skirmishes and window breaking. The first prisoners had been kept locked in their cells, but we were allowed freedom during the day to roam around the corridors from eight in the morning until eight at night. On the other side of the female quarters were the cells for colored prisoners, most of whom seemed to be doing some sort of work around the jail. There were three girls awaiting trial for murder and many who had been arrested in stabbings and general disorderly conduct while drinking. These prisoners kept up their chatter after eight o’clock and the matron kept puffing around the place trying to quell the giggling, singing and quarreling.

Before the doors were closed for the night, and after the work of the day was done, there were card games and dances in the corridors, some of the girls dancing and the others beating time and singing.

In Washington’s City Jail they waited out the rest of their sentences with far more comfort than they had begun. Dorothy Day’s arrest several weeks prior had been in service of the many women whose struggles were not alleviated: women who were force-fed daily or whose civil rights had otherwise been infringed upon.

Her imprisonment had not been an easy one. The brutality she faced upon her arrival at Occoquan, the starvation that had reduced her to such a place of faithlessness, and the sense of overwhelming injustice that very nearly broke her, marked her in such a way that she spent the remainder of her life devoted to justice and equality for all people. ![]()

Silent Sentinels and the Night of Terror

Introduction & Table of Contents

Voices from Occoquan

Introduction & Table of Contents

1917 Suite: A Month, a Year, a Term of Liberty

Introduction & Cross-issue Table of Contents