print preview

print previewback 1917 SUITE | SILENT SENTINELS AND THE NIGHT OF TERROR

VOICES FROM OCCOQUAN

Excerpt from Jailed for Freedom: “Administrative Terrorism”

reprinted from Jailed for Freedom, Doris Stevens, 1920

The Administration tried in another way to stop picketing. It sentenced the leader, Alice Paul, to the absurd and desperate sentence of seven months in the Washington jail for “obstructing traffic.”

With the “leader” safely behind bars for so long a time, the agitation would certainly weaken! So thought the Administration! To their great surprise, however, in the face of that reckless and extreme sentence, the longest picket line of the entire campaign formed at the White House in the late afternoon of November 10th.

|

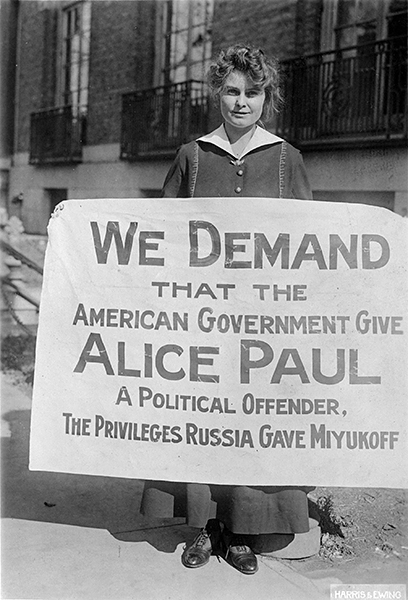

| Lucy Branham protesting the political imprisonment of Alice Paul Harris & Ewing Photography Washington, D.C., 1917. |

Forty-one women picketed in protest against this wanton persecution of their leader, as well as against the delay in passing the amendment. Face to face with an embarrassing number of prisoners the Administration used its wits and decided to reduce the number to a manageable size before imprisoning this group. Failing of that they tried still another way out. They resorted to imprisonment with terrorism . . .

. . . There were exceptionally dramatic figures in this group. Mrs. Mary Nolan of Florida, seventy-three years old, frail in health but militant in spirit, said she had come to take her place with the women struggling for liberty in the same spirit that her revolutionary ancestor, Eliza Zane, had carried bullets to the fighters in the war for independence.

Mrs. Harvey Wiley looked appealing and beautiful as she said in court, “We took this action with great consecration of spirit, with willingness to sacrifice personal liberty for all the women of the country.”

Judge Mullowny addressed the prisoners with many high-sounding words about the seriousness of obstructing the traffic in the national capital, and inadvertently slipped into a discourse on Russia, and the dangers of revolution. We always wondered why the government was not clever enough to eliminate political discourses, at least during trials, where the offenders were charged with breaking a slight regulation. But their minds were too full of the political aspect of our offense to conceal it.

“The truth of the situation is that the court has not been given power to meet it,” the judge lamented. “It is very, very puzzling—I find you guilty of the offense charged, but will take the matter of sentence under advisement.”

And so the “guilty” pickets were summarily released.

|

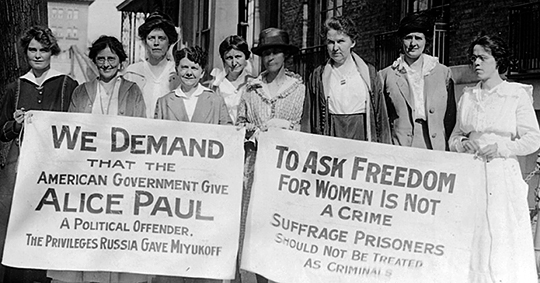

| National Woman’s Party members protesting the political imprisonment of Alice Paul, including Lucy Branham, Lucy Burns, Mary Winsor, among others. Washington, D.C., 1917. |

The Administration did not relish the incarceration of forty-one women for another reason than limited housing accommodations. Forty-one women representing sixteen states in the union might create a considerable political dislocation. But these same forty-one women were determined to force the Administration to take its choice. It could allow them to continue their peaceful agitation or it could stand the reaction which was bound to come from imprisoning them.

And so the forty-one women returned to the White House gates to resume their picketing. They stood guard several minutes before the police, taken unawares, could summon sufficient force to arrest them, and commandeer enough cars to carry them to police headquarters.

As the Philadelphia North American pointed out: “There was no disorder. The crowd waited with interest and in a noticeably friendly spirit to see what would happen. There were frequent references to the pluck of the silent sentinels.”

The following morning the women were ordered by Judge Mullowny to “come back on Friday. I am not yet prepared to try the case.”

Logic dictated that either we had a right to stand at the gates with our banners or we did not have that right; but the Administration was not interested in logic. It had to stop picketing. Whether this was done legally or illegally, logically or illogically, clumsily or dexterously, was of secondary importance. Picketing must be stopped!

Using their welcome release to continue their protest, the women again marched with their banners to the White House in an attempt to picket. Again they were arrested. No one who saw that line will ever forget the impression it made, not only on friends of the suffragists, but on the general populace of Washington, to see these women force with such magnificent defiance the hand of a wavering Administration. On the following morning they were sentenced to from six days to six months in prison. Miss Burns received six months.

In pronouncing the lightest sentence upon Mrs. Nolan, the judge said that he did so on account of her age. He urged her, however, to pay her fine, hinting that jail might be too severe on her and might bring on death. At this suggestion, tiny Mrs. Nolan pulled herself up on her toes and said with great dignity: “Your Honor, I have a nephew fighting for democracy in France. He is offering his life for his country. I should be ashamed if I did not join these brave women in their fight for democracy in America. I should be proud of the honor to die in prison for the liberty of American women.” Even the judge seemed moved by her beautiful and simple spirit.

|

| Mrs. Nolan Harris & Ewing Photography Washington, D.C., February 10, 1921. |

In spite of the fact that the women were sentenced to serve their sentences in the District Jail, where they would join Miss Paul and her companions, all save one were immediately sent to Occoquan workhouse.

It had been agreed that the demand to be treated as political prisoners, inaugurated by previous pickets, should be continued, and that failing to secure such rights they would unanimously refuse to eat food or do prison labor.

Any words of mine would be inadequate to tell the story of the prisoners’ reception at the Occoquan workhouse. The following is the statement of Mrs. Nolan, dictated upon her release, in the presence of Mr. Dudley Field Malone:

It was about half past seven at night when we got to Occoquan workhouse. A woman [Mrs. Herndon] was standing behind a desk when we were brought into this office, and there were five or six men also in the room. Mrs. Lewis, who spoke for all of us, . . . said she must speak to Whittaker, the superintendent of the place.

“You’ll sit here all night, then,” said Mrs. Herndon.

I saw men begin to come upon the porch, but I didn’t think anything about it. Mrs. Herndon called my name, but I did not answer. . . .

Suddenly the door literally burst open and Whittaker burst in like a tornado; some men followed him. We could see a crowd of them on the porch. They were not in uniform. They looked as much like tramps as anything. They seemed to come in—and in—and in. One had a face that made me think of an ourang-outang. Mrs. Lewis stood up. Some of us had been sitting and lying on the floor, we were so tired. She had hardly begun to speak, saying we demanded to be treated as political prisoners, when Whittaker said:

“You shut up. I have men here to handle you.” Then he shouted, “Seize her!” I turned and saw men spring toward her, and then some one screamed, “They have taken Mrs. Lewis.”

A man sprang at me and caught me by the shoulder. I am used to remembering a bad foot, which I have had for years, and I remember saying, “I’ll come with you; don’t drag me; I have a lame foot.” But I was jerked down the steps and away into the dark. I didn’t have my feet on the ground. I guess that saved me. I heard Mrs. Cosu, who was being dragged along with me, call, “Be careful of your foot.”

Out of doors it was very dark. The building to which they took us was lighted up as we came to it. I only remember the American flag flying above it because it caught the light from a window in the wing. We were rushed into a large room that we found opened on a large hall with stone cells on each side. They were perfectly dark. Punishment cells is what they call them. Mine was filthy. It had no window save a slip at the top and no furniture but an ironed bed covered with a thin straw pad and an open toilet flushed from outside the cell. . . .

In the hall outside was a man called Captain Reems. He had on a uniform and was brandishing a thick stick and shouting as we were shoved into the corridor, “Damn you, get in here.”

I saw Dorothy Day brought in. She is a frail girl. The two men handling her were twisting her arms above her head. Then suddenly they lifted her up and banged her down over the arm of an iron bench—twice. As they ran me past, she was lying there with her arms out, and we heard one of the men yell, “The —— suffrager! My mother ain’t no suffrager. I’ll put you through ——.”

At the end of the corridor they pushed me through a door. Then I lost my balance and fell against the iron bed. Mrs. Cosu struck the wall. Then they threw in two mats and two dirty blankets. There was no light but from the corridor. The door was barred from top to bottom. The walls and floors were brick or stone cemented over. Mrs. Cosu would not let me lie on the floor. She put me on the couch and stretched out on the floor on one of the two pads they threw in.

We had only lain there a few minutes, trying to get our breath, when Mrs. Lewis, doubled over and handled like a sack of something, was literally thrown in. Her head struck the iron bed. We thought she was dead. She didn’t move. We were crying over her as we lifted her to the pad on my bed, when we heard Miss Burns call:

“Where is Mrs. Nolan?”

I replied, “I am here.”

Mrs. Cosu called, “They have just thrown Mrs. Lewis in here, too.”

At this point Mr. Whittaker came to the door and told us not to dare to speak, or he would put the brace and bit in our mouths and the straitjacket on our bodies. We were so terrified we kept very still. Mrs. Lewis was not unconscious; she was only stunned. But Mrs. Cosu was desperately ill as the night wore on. She had a bad heart attack and was then vomiting. We called and called. We asked them to send our own doctor, because we thought she was dying. . . . They [the guards] paid no attention. A cold wind blew in on us from the outside, and we three lay there shivering and only half conscious until morning.

“One at a time, come out,” we heard some one call at the barred door early in the morning. I went first. I bade them both good-by. I didn’t know where I was going or whether I would ever see them again. They took me to Mr. Whittaker’s office, where he called my name.

“You’re Mrs. Mary Nolan,” said Whittaker.

“You’re posted,” said I.

“Are you willing to put on a prison dress and go to the workroom?” said he.

I said, “No.”

“Don’t you know now that I am Mr. Whittaker, the superintendent?” he asked.

“Is there any age limit to your workhouse?” I said. “Would a woman of seventy-three or a child of two be sent here?”

I think I made him think. He motioned to the guard.

“Get a doctor to examine her,” he said.

In the hospital cottage I was met by Mrs. Herndon and taken to a little room with two white beds and a hospital table.

“You can lie down if you want to,” she said.

I took off my coat and hat. I just lay down on the bed and fell into a kind of stupor. It was nearly noon and I had had no food offered me since the sandwiches our friends brought us in the courtroom at noon the day before.

The doctor came and examined my heart. Then he examined my lame foot. It had a long blue bruise above the ankle, where they had knocked me as they took me across the night before. He asked me what caused the bruise. I said, “Those fiends when they dragged me to the cell last night.” It was paining me. He asked if I wanted liniment and I said only hot water. They brought that, and I noticed they did not lock the door. A negro trusty was there. I fell back again into the same stupor.

The next day they brought me some toast and a plate of food, the first I had been offered in over 36 hours. I just looked at the food and motioned it away. It made me sick. . . . I was released on the sixth day and passed the dispensary as I came out. There were a group of my friends, Mrs. Brannan and Mrs. Morey and many others. They had on coarse striped dresses and big, grotesque, heavy shoes. I burst into tears as they led me away.

(Signed) Mary I. Nolan.

November 21, 1917.

Silent Sentinels and the Night of Terror

Introduction & Table of Contents

Voices from Occoquan

Introduction & Table of Contents

1917 Suite: A Month, a Year, a Term of Liberty

Introduction & Cross-issue Table of Contents