print preview

print previewback BRIAN BOULDREY

One Singer to Mourn

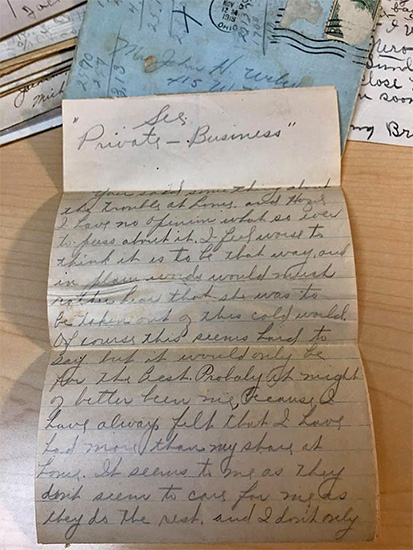

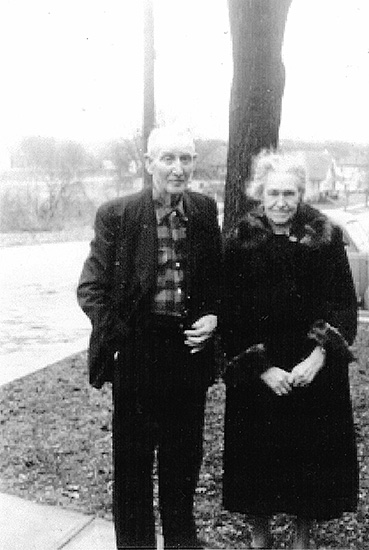

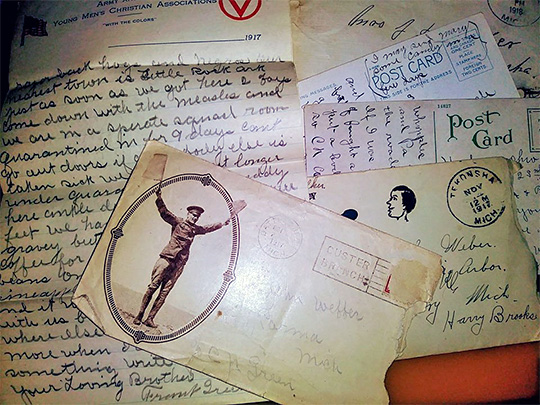

On the death of my grandmother, Mary Bouldrey, née Weber—whom I loved with an unfair but earned preference—at the age of ninety-eight, I received as my inheritance her flour and sugar canisters, an accomplished amateur painting of a deer in a winter landscape, and a packet of letters she had squirreled away, letters addressed to her mother, my great-grandmother, Hazel. The letters are from the years 1917 to 1920, the years just after she married her husband John and before she really started getting busy with raising babies, which takes away from your letter-writing time.

Besides, she and her many brothers and sisters (I can’t quite get an exact count—at least eight), all becoming adults, all raised on the same southern Michigan farm, were about as scattered as they’d ever been or would ever be. One sister, Rita, had run off to Toledo to do hair and convert to Catholicism; another, Ila, brain damaged as a result of surviving a terrible fever when she was a toddler, got knocked up by a stranger taking advantage of her disability. Ila got help raising bastard Leo—whom I had known, though I didn’t realize he was Uncle Leo the Bastard—by brothers Charlie and Jack. It doesn’t seem beside the point to say that Rita wrote of Ila’s scandal in 1917:

I feel worse to think it is to be that way, and in plain words would much rather hear that she was to be taken out of this cold world. Of course this seems hard to say but it would only be for the best.

But my family doesn’t easily or willingly depart this cold world. We tend to overstay our welcome, and then, suddenly, bid a French Exit to the party of life.

Eight Green children, at least: that’s a lot of siblings writing lots of letters. (If genealogy is a relaxing hobby for you, then consider how unrelaxing it might be for a rabbit. I come from a long line of healthy, oversexed farm families.) But above all, the bulk of the letters came from her two other brothers, first Frank, then Emmet, both having enlisted in two different battalions in the army to fight in the Great War.

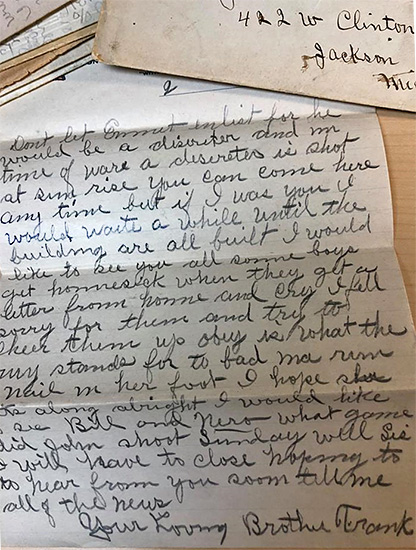

Of the nearly fifty letters and cards, about half of them are written to Hazel by Frank, a can-do mule skinner for Company A of the 328th Machine Gun Battalion—he had a way with an image, and he proves his blood connection to me for, despite all our faults, I also come from a long line of impeccable spellers. However, Frank seemed to believe that using punctuation would make it possible for the devil to take his soul, and the effect of his pauselessness is that of a fever dream, swinging from one fact to another without hope for an intake of breath:

Dear Madam and Adam,

Don’t let Emmet enlist for he would be a deserter and in time of war a deserter is shot at sunrise you can come here any time but if I was you would wait a while until the buildings are all built I would like to see you all some boys get homesick when they get a letter from home and cry I felt sorry for them and try to cheer them up obey is what the army stands for too bad ma run a nail in her foot I hope she gets along all right I would like to see Bill and Nero [his beloved hunting dogs]—what game did John shoot Sunday well sis I will have to close hoping to hear from you soon tell me all of the newsYour loving brother Frank

I know he is blood, too, because he loves to project: here, he speaks of the homesickness of his pals but not his own and lets his love for the dogs stand, perhaps, for home, and he is of such a hardy stock no bullet, kicking mule, or disease can kill him.

There is a curious pleasure reading these letters to my great-grandmother while having none of her own she sent out. It is the pleasure of whodunits, or the pleasure poets must enjoy when translating Sappho’s fragments and offering their own imagined words to match the size of thoughts gone missing in the scroll holes. What is clear if not provable to me is that Great-Grandma Hazel was a generous writer, a peacemaker, not a gossip but one to confide in; family was important to her, and she was, like the rest of the Greens, healthy. That which does not kill the farmer makes him smelly. Though I am three generations from manure, I am predisposed to liking farm folk, perhaps because they have fewer hangups about sex and other bodily functions, having been around all that animal husbandry.

As I read the letters from Frank, and then Emmet and Rita and their mother, as well as a few family friends, and transcribed them, I managed to piece together a story with several curious themes. For example, besides spelling words well and expressing love more effusively toward pets than people, we are also “ungifters”—there must be half a dozen instances in which various items of (farm) value (bags of seed, tire irons, hunting dogs) are given, but then recalled or simply taken back unceremoniously. This is generally accepted as a family trait, and no quarrels arise from the welching. But the story that really rises from a subterranean place among the letters is a thing still true: my family is astonishingly impervious to disease, decay, and death. My great-great-uncle and his brothers and sisters all discuss, over the three years of letters, friends and neighbors and coworkers and employers who fall to measles, chicken pox, and the grippe. In other words, what turned out to be the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918. It visited them all, and chose to pass them by.

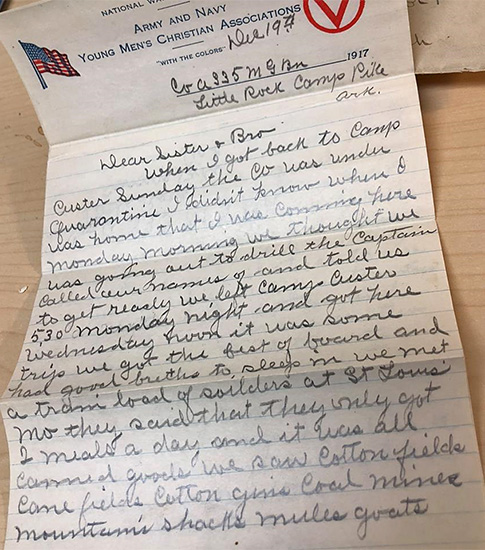

At one point in late 1918, Uncle Frank's entire platoon is suddenly in quarantine at a camp in Ohio, and he alone is shipped, without warning, to Camp Custer in Arkansas; though it is not explicit, I feel confident that this was done to protect him from the infected, and for a while, he is the only healthy soldier trained to tend the mule team:

When I got back to camp Sunday the whole Co was under quarantine I didn’t know when I was home that I was coming here [Camp Custer in Little Rock, Arkansas] Monday morning I thought I was going out to drill the Captain called my name off and told us to get ready we left Camp Custer 530 Monday Night and got here Wednesday noon it was some trip I got the best of board and had a good bunk to sleep in I met a tram load of soldiers at St. Louis MO they said that they only got 2 meals a day and it was all canned goods we saw cotton fields cane fields cotton gins coal mines mountains shacks mules goats razor back hogs and negros our nearest town is Little Rock Ark just as soon as we get here 2 boys come down with the measles and we are in a separate squad room quarantined in for 9 days can’t go outdoors if any body else is taken sick we will be put longer under quarantine it is muddy here ankle deep and sticks to our feet we had beef steak peas tomatoes gravey butter bread potatoes and coffee for dinner for supper stew beans onions in milk tomatoes pineapple sauce bread and tea and it was good Nelson Coarser was with us but they took him somewhere else in camp I will write more when I can get out and see something write often

It was called the Spanish flu because Spain, early on, was hit hard by it—but so was the rest of Europe—and Spain was quite open with their statistics, both to warn and help. Naming the flu after its most honest and well-meaning victim is the very definition of insult to injury, but then there was that vicious joke in the late ’80s: “Q: What does GAY stand for? A: ‘Got AIDS Yet?’” You are silent for fear of being a scapegoat, but silence, besides equaling death, also isolates you. Shames you. And causes trouble for others. In the early ’90s, I wrote a series of “hard-hitting” AIDS advocacy pieces, but under the pseudonym Alec Holland, which you’d know, if you’re a comic book geek, was the name of Swamp Thing before he became Swamp Thing. I did it because I wanted to hit hard, but I also did it because I was HIV-positive and didn’t want my friends or family to know, and by know, I mean “worry.”

“Coming out” of any sort is exhausting. A kid realizing he’s gay doesn’t just realize he’s gay. There are inklings, or perhaps there is the thunderstruck moment, but after that comes the Kubler-Ross journey from anger to denial to fear to that final admission that you like nice sweaters and Cher’s endless farewell tours. Coming out can take months, years, even destroyed marriages. And when you tell another person you are gay, you have to grab a magazine and wait for them to go through the same steps toward acceptance. And you come out to friends and family one at a time. And you have to wait. For every single person.

And so it goes with carrying a fatal disease. Clearly, I survived, and eventually came out to the world through novels and memoirs that I assumed nobody read. Hooray for me, sure, but I think it’s important to say that those who outlive a pandemic do not necessarily live in what Susan Sontag calls “the kingdom of the well.”

The second, lethal wave of the Spanish flu came at the tail end of the First World War, when Americans were suddenly conveniently gung ho about killing the Bosch when things were pretty much winding down. An early, weaker version of the virus created some discomfort nearly a year before in the first months of 1918, but killed nearly nobody. The second wave arrived in Boston in September 1918 and spread quickly and without pattern. Even so, every red-blooded American male who could enlist enlisted. Not enlisting meant you were a slacker, which may be why Emmet signed up despite Frank’s goading warning. Frank writes that they are packed six to a tent over in France, among people of many lands, some of whom he is racist toward:

I am glad that they didn’t put any Dagos with me when a bunch of them talk they sound like a bunch of geese a cackling to me I took my laundry to a farmers house the woman chewed snuff she chewed the end of a match and then dipped the match in the snuff the next time I go there I am going to have her give me lessons in spitting

Alfred Crosby, the great historian of the flu epidemic (author of America’s Forgotten Pandemic), wrote about the delayed shock most of rural America experienced when they were informed they had experienced a plague. While those in the cities knew full well they were experiencing an epidemic, in a pre–mass media, small-town America, “when you talk to people who lived through it, they think it was just their block or just their neighborhood.” It was not apparent to the world that there actually was a flu epidemic until the annual Farmer’s Almanac noted in 1918 that life expectancy had dropped from fifty-one years to thirty-nine.

We give to war and gunmen in schools and terror attacks and train derailments sensational news headlines because they come, almost automatically, in neat, powerful packages with a beginning, middle, and end, because we can see that shape even in the moment of tragedy. Epidemic is such a sprawl, unshapeable, ending not with a bang but with a whimper; you can’t map an epidemic as you can zones of war, nor can you write “Here Be Dragons” to warn people away. There is no transformative, enlightening message, no silver lining, no troubadour or bard to give prosody to chaos. And when it’s finally over, nobody wants to talk about it, nobody wants to do that work of transformation—you are either dead or exhausted. And always isolated with the experience.

It also has its stops and starts, willful or accidental censorships: some things are just better left unsaid. Or, as it lies buried but mentioned in nearly every letter from the years 1917 to 1919:

Nov. 11 1917

Dear Brother & Sister

Received your most welcome letter and was sure glad to hear from you but sorry Hazel has been ill. Hope she is better by this time and are all well at present. Jennarose has had the chicken pox but she wasn’t a bit sick with them and it’s all over with them now. Harry is busy all the time has lots of work. We have got a nice little place over here.

Jennarose has the chicken pox but she’s just fine. Reading the lopsided correspondence among the siblings is like watching an in-flight movie with a scene with a plane crash or violent turbulence cut out so as not to disturb passengers, jumping to a scene in which characters are dead and we have no idea how that happened. As if the experience is terrible but the aftermath perfectly bearable.

One of the few signs of weakness (that is even mentioned among the women and men of that side of the family) is referred to by a family member, speaking of my great-great-grandmother:

Your mother has given of the best of her life & strength (her youth) to her family & her road has not been smooth but I’m sure it has been a labor of love. I was indeed sorry to hear that so many had come upon her for such a long stay & she with those delicate ankles.

As a seasoned through-hiker, I know I am my great-great-grandmother’s great-great-grandson. We both have very delicate ankles.

In the mid-’90s of San Francisco, I complained bitterly (and even wrote a bitter, complaining novel) that the sumptuous plenitude of the Boom Economy, with its tech money and high-end restaurants and full employment, made it impossible to get anything done—it was crowded and expensive and full of strangers. What I now realize is that I had become used to living in a relative ghost town, where the sick were too sick to go to the movies or a restaurant—I had them all to myself, and that was, for too much of my experience, normal. Even today, I have a terrible time standing in line.

In Shakespeare’s Henry V, the Duke of Burgundy tells the victorious Harry—who, for all his risk, didn’t lose much in the Battle of St. Crispian’s Day and is pretty psyched about having a hot new French wife—that France is really suffering after ten thousand able-bodied men died on the battlefield:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . let it not disgrace me,

If I demand, before this royal view,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . in this best garden of the world

Our fertile France, put up her lovely visage?

Alas, she hath from France too long been chased,

And all her husbandry doth lie on heaps,

Corrupting in its own fertility.

Her vine, the merry cheerer of the heart,

Unprunèd dies; her hedges even-pleached,

Like prisoners wildly overgrown with hair,

Put forth disordered twigs; her fallow leas

The darnel, hemlock, and rank fumitory

Doth root upon, while that the coulter rusts

That should deracinate such savagery.

Nobody is there to manage the land or make the wine, and Shakespeare sees horror there, as survivors of the 1918 epidemic were deeply troubled by movie theaters playing Mickey and Tarzan of the Apes to nobody, unsold produce in the market, public transport circling the city endlessly and riderless, funerals all day and ambulances all night. Branches crack with unpicked apples. Nothing says death like vigor mortis.

And the survivor feels guilt. My HIV doctor, who also has HIV, doesn’t believe in survivor guilt but, having been a great warrior in the epidemic, instead sees it as a form of PTSD (and lest you tsk at a doctor who ought to heal himself, I remind you of Chekhov’s doctor in “The Grasshopper,” whose end is icky in any language, though particularly gross in English, as he develops diphtheria by “sucking up the mucus through a pipette from a boy” with the disease in order to kill himself after he figures out his wife is untrue—that is, that the person he loves is gone). I’m going to let my doctor have PTSD: he went to war, while I served in a sort of civilian work council, and I always feel guilty because I think I should have done more, like my doctor. I can see great-great-uncle Frank watching the infirmary fill; I can sense he feels both overworked by the mules and utterly useless around his sick companions. What can you do, besides pray and skin the mules?

Saint Roch, in the Catholic tradition, a survivor of plague, is the saint you invoke against the plague (hagiography is funny like that: the patron saint of bridges is Saint John of Nepomuk, a guy who was martyred when they threw him off a bridge). Saint Roch was a fourteenth-century mendicant pilgrim from the French foothills of the Pyrenees, who, on his way to Rome, encountered great numbers of people suffering from the bubonic plague. He put down his walking stick and did everything he could to nurse and comfort the sick and dying. Inevitably, he became part of the epidemic and, in order to avoid spreading it to anybody else, went out into the wilderness to die. But God took pity on him and sent, each day, a little dog that brought him bread and licked his wounds until they healed. He is typically seen with the walking stick and drinking gourd, the dog at his feet with a mouthful of bread, and he lifts his robes to point to his rather vaginal-looking bubo wound. Besides being the patron of plague sufferers, he is also the patron of dogs, the falsely accused, and bachelors. Needless to say, I like this guy. And the part of the story where he has been infected and isolates himself in the woods—that resonates quite a bit for those who survive or outstrip a plague.

In my home, there are at least five devotional statues of Saint Roch. I say “at least” because there must be just as many, again, in states of disrepair: his drinking gourd falls off, the little dog comes unglued from his pedestal. One terrible but beloved statue was painted by a palsied nun on the island of Madeira—he looks like he has mascara on and has just eaten raw flesh, and his dog is serving him a bagel. Roch inspires me, but his leadership may be questionable. Should I, as I have—at least spiritually—gone into the woods to isolate myself from others so as not to give them the plague? Not just the dormant HIV, but the sorrowful memories, the long, untransformable story you know will have an unhappy ending—why would I do that to people?

I hear myself in the letters and actions of other survivors. The strange writer Norman Douglas, who survived the Spanish flu and lived far beyond his rights, for example, just kept traveling, for all at home were dead. That’s another sorrow of the survivor: it unhomes you. As Paul Fussell describes Douglas’s constitution in Abroad, “Instead he was raggedy, although he managed to maintain, as Harold Acton recalled, ‘the elegance of a Scottish Jacobite in exile.’ His constitution was rugged. After a lifetime of excesses—confronted by temptation he always followed his own favorite suggestion, ‘Why not, my dear?’—he apparently couldn't die, even at the age of eighty-four, and he finally had to put himself down with an overdose of pills.”

The phrase to linger upon is “Scottish Jacobite in exile.” Those who live forever find themselves removed from the arc and shape of typical lifespans. It’s why Tolkien’s elves didn’t want to get emotionally involved with mortal men, and why my grandmother, who lost my grandfather in 1978, went on for what I’d call another lifetime, forty years, without considering another man, before she passed at the age of ninety-eight. My grandmother, though the eldest of her siblings, outlived all of them, too. “Death always leaves one singer to mourn,” wrote Katherine Anne Porter, herself a survivor of the Spanish flu epidemic. Note that this lyrical bromide has been applied to nearly every single horror movie ending ever made.

Just because we are unhomed does not mean there’s not work to be done. Great-great-grandma Green, a tough old bird and a piece of work by any standards, she of the delicate ankles, finds herself doing the laundry for everybody in town as they languish sick in bed:

April 26 1919

Well, Hazel I can see you going to the post office every day looking for a letter from ma & then going home and saying darn it why don’t Ma write? But when I tell you all I have done this week you will say no wonder she didn’t write—Monday I washed for Georgia Ford & some for her mother in the forenoon. Afternoon I did Libbie’s generals, washing three washings one day, Tuesday, I did George Broncing and was going to do my washing and it rained. I had George Eban dress for dinner on Tuesday & Wednesday I had Ina (Ila) Ness come & George for dinner. I did my washing. Georgia Ford and George Broncing and George Eban had the grip. The [somebody’s name] came on Tuesday about two o clock & when I ans the ring, Wilda was the one to call she was Rob Chapels she came home with the red measles & had them good & proper she said she wasn’t sick But Wednesday I made her stay in bed til five o’clock I was washing and had the doors open I though the fresh air wasn’t good for her she has got Pheneralogy I guess you can tell what that word is her face is swelled to beat to faces good spelling what gives her…

I remember the year or so, 1992 into 1993, when my partner Jeff was fading—fighting his own good fight but too exhausted to do anything else. I would come home from a long day at work, exhausted, and start up another round of work cooking and cleaning up the house and him. He was not a burden. Nevertheless, I was doing heavy lifting. And the work never quite got done. Just reading about all that laundry in my great-great-grandmother’s letter makes my shoulders ache.

Meanwhile, Uncle Frank had his own tasks. Reading between the unpunctuated lines of his and others’ letters, Uncle Frank was, it strikes me, a likable guy—people liked to write to him and send him gifts, and he called out to all his seven or so brothers and sisters with fond hellos at least once. But in almost every letter he misses Nero, his beloved hunting dog:

keep my pal Nero a hunting every chance you get for I know how he likes it…

I am glad John likes his new job they told us today that we would get out of quarantine Saturday morning I will be home if nothing more happens I’ll bet Nero had a big time over to your place we are 3 weeks behind in our drilling and now we are going to make it up so you see we have some hard work ahead of us we are going to stay in the trenches some night this week…

Butter Scotch is good to eat but “Gilberts Chocolates” are lots better. Fido is a good old dog but Nero is a lot better…

The only thing he mentions more often than Nero is, well, people getting sick all around him. And he can do nothing about Nero or sickness.

The Spanish flu targeted specifically, if not exclusively, young adults between the ages of twenty and forty. Your basic workforce, adults with parents still living. While, as the cultural critic Fran Lebowitz pointed out in “On Race and Racism” that “genocides are like snowflakes, each one unique, no two alike,” the young men from twenty to forty who fell to AIDS left a similar hole in the population. The world became a desolate landscape of bereft parents, orphans, and widowed spouses. My partner Jeff—who, you will not be surprised to discover, grew up on an Illinois farm that raised polled shorthorns—had three siblings, and they, along with his parents Joe and Joyce, all had names that began with the letter J. He was buried in 1993 back in his hometown in a lovely little cemetery along a river, and twice daily the Burlington Northern trains roll by and give a lonesome whistle salute. When Joyce, good country people, also lost her husband a few years ago, she had a large family headstone placed for father and son and eventually the rest of them, and specifically ordered that a square hole be chiseled through the stone. Little hinged windows cover the square, and in that hole-in-the-rock space, she rearranges daily little groupings of toy cows, farmers, and tractors. She plays house in the tombstone. “Why weepest thou?” asks the angel to the Marys at Jesus’s tomb, by which he means, what are you doing hanging around a cemetery? Because, Joyce would say, playing house in the tombstone, this isn’t a cemetery, this is home.

“What is home?” asks Mary Lee Settle in her novel Celebration, “The place where you can die.” The loss of family is, to me, the loss of home—whether you are shunned by family or if family dies out. You wander the earth like the prodigal son, but there is no place to return to. After a while, you stop looking for home and start looking for a cemetery. It’s not that one is eager to get into the grave, but survivor guilt is real, and one begins to do things that might hasten the journey. Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider tells the story of a woman who survives the flu epidemic only to find, after a delirious fever dream, that her soldier boyfriend died of it, probably because he caught it from her when caring for her. The last paragraph is worth quoting in full:

No more war, no more plague, only the dazed silence that follows the ceasing of the heavy guns; noiseless houses with the shades drawn, empty streets, the dead cold light of tomorrow. Now there would be time for everything.

Literary fiction seems the appropriate realm of plague, not because it feels unreal or untrue, but because the wound of the loss of all those people is a wound that never heals, like Saint Roch’s bubo he always reminds us of in the statuary. Fiction is the place where one can write again and again, with invention and artfulness, the disease and death not an engine—that is, the thing itself—but a spirit, a myth. Half a dozen of William Maxwell’s novels and stories (my favorite being So Long, See You Tomorrow) concern a young boy whose mother dies in the 1918 flu epidemic, and the loss remains as acute as the day the cut wounded. You would think the tale would get repetitive, but pain is a pilgrim, and can find a home anywhere.

There is one more letter you need to see. Once Frank got to France, the war was nearly over, and he was just there to bury the dead and marvel at the unpicked grapes among the vineyards. He wrote this:

Savenay, France

February 15, 1919

Dear Sis & Bro

I will write you a few lines to let you know I am still among the living How is everybody at home I hope they are fine and dandy I am a doing guard duty just now I left Paris xmas day and that was a trip that I will always remember as long as I live I would like to get home so I could start work in the spring I mean in March or April I have to have five hundred bucks by first of next January and it is going to make me do some figuring I think eh I can’t tell why I have got to have this money just now but just wait a little while and you will see for your self

How is mother I wrote her a few days ago but I haven’t got an answer yet Well I must close for this time so good-by

From Your

Loving Brother

Five hundred dollars was a lot of money back then, as we say. Whether he got it or not is part of a larger mystery, because here’s the most important thing to tell you: Frank never came home. Another French Exit. Nobody knows where he went—the best guess was California. With a girl? With a French girl? Efforts were made, but he disappeared, despite an extended loving family he seems to have had no quarrel with, and Nero, faithful Nero, waiting like Ulysses’s old hunting dog Argos, keeping himself alive till the day Frank returned. Part of me doesn’t blame Uncle Frank. People were going to ask him stories he didn’t want to tell.

Since most rural folks didn’t, as Crosby points out, know they were living in a pandemic until the new issue of the Farmer’s Almanac was published, there are few direct references to deadly contagion in my grandmother’s letters. Perhaps the most pointed touch upon the trauma is in a letter postmarked from Chicago in February 1919, from Claudine, grandma Hazel’s best friend (I think she had a little crush on Uncle Frank), in which she would seem to be referring to a survivor of the flu (not always a good thing, as your lungs would not ever work well again, and convalescence sometimes took years):

Father’s health seems to be picking up. He has had one terrible fight & La La’s been very brave.

And traumatic events are often too difficult to write about in a direct, historical way even once, let alone many times. My great-grandmother’s letters from ground zero of the flu epidemic follow Emily Dickinson’s instructions, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant,” as “the truth must dazzle gradually or every man be blind.” As somebody who makes a life as a writer, sometimes telling tales and sometimes telling truth, it has been a lesson slowly learned that people who do not tell tales, people who, in fact, are often wrapped in silence and self-distancing, are not necessarily storyless. And they are certainly not without feeling. Silence and distance are not indications of a lack of care, but perhaps a clue that one might care too much, that one might not want you to worry. I’m thinking, for example, of Uncle Frank alone with the mules and homesick for his family but only admitting he misses Nero; I’m thinking of Aunt Rita in Toledo wondering whether her own damaged sister might be better off dead, if only to spare Ila the pain of life; I’m thinking of Saint Roch retiring to the woods with his bubos and his memories of plague. And I’m thinking of my old self and my cloak and dagger pseudonyms and omission of infection, and the long journey toward telling this story now—quarantine is what we learned, and quarantine is how we continue to live. ![]()