print preview

print previewfrom Scholarship Boy

Where Are You From?

I followed Willie around the counter and down a narrow passageway. He stopped in front of another curtain, a black one, and told me to stay close to him as he pulled it to one side. He tugged my hand as he did so, urging me to follow him into the shadowy space the curtain created around a closed door. Total darkness descended when he let the dark fabric fall behind us. Was this the darkroom? I heard Willie rattling the door’s knob and suddenly his hand appeared, bathed in an eerie red light that now streamed into our curtained cavern. What are these strange smells? Willie urged me on again with a tug on my fingers, this time into the darkroom itself, as he quickly shut the door behind us.

|

|

| Larry and Louise St. Louis, 1948 Photo by Willie Palmer |

|

“Stand still. It’s going to take a few minutes for your eyes to adjust to this light,” he said. I had to open and close my eyes a few times before I could begin to make out shapes and depth. There were clothespins holding pieces of paper on lines strung around the room. Willie dropped my hand. I sensed he was moving away. I followed the sound of his footsteps and could make out the back of his head in the red dimness. I focused on where he stood and could see his hand reach up. I heard a faint clicking noise. A dim white light came on and beamed down onto a narrow counter similar to the one out front.

A cloudy whiteness seemed to seep into the red atmosphere hovering over everything in the room. I looked around and noticed that the pieces of paper on the clotheslines had pictures of people on them. I could make out Willie’s face, too, now, wrapped in its red halo. He stood next to the machine that was spilling white light down onto the counter. Willie explained in quiet tones that it was used to enlarge photographs.

I could feel the concrete floor beneath my feet. It felt like the floor in our basement at home, but was hidden in the deep shadows beneath the counter.

As he excitedly adjusted various levers and buttons I could not see from where I stood, Willie announced he was about to astonish me. His voice grew more and more enthusiastic as he explained he was going to show me how a picture taken with a camera became a photograph on a piece of paper.

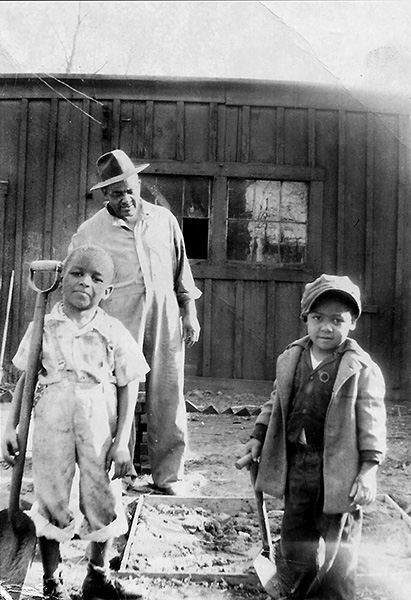

|

|

| Larry and Barry mixing cement with father, Arglister Palmer St. Louis, ca. 1950 Photo by Willie Palmer |

|

He continued to lecture the air above my head, tossing out terms like developer, fixer, stop bath, and silver bromide. Since I would not grasp most of this chatter until much later, I just stood there, barely nodding in response, skeptically unimpressed. But when Willie’s chatter disappeared into the deep red silence, just at the moment he placed a sheet of the slick photographic paper into the solution in a tray on the counter, I leaned in for a closer look. Murky gray shapes began to form over some parts of the paper, as if someone had spilled ink there. The hue of a hazy sky took on the curves of an oval. Parts of the sheet continued to darken while others grew paler, brighter, white nearly—even in the dim red light. I gulped, flabbergasted, as I realized that a face, a smiling face, was now looking up at me from the bottom of the shallow pool.

|

|

| Larry and Barry mixing cement St. Louis, ca. 1950 Photo by Willie Palmer |

|

~

I drew upon all the insights and advice Willie had shared with me over the years when, early in my first semester, I interviewed to be a photographer for The Exonian, the student newspaper at Exeter. The photography editor, Tom, asked me about my previous experience, and I reeled off stories about what Willie had taught me, emphasizing the fact that I had not actually developed film or made prints before. I told Tom what I knew about light meters and cameras, and about the cameras I had used, which included Willie’s 35mm Pentax camera as well as my own Kodak Brownie, an inexpensive and small box-like camera that, in those days, children just beginning to practice photography received as gifts.

Tom seemed impressed and offered to be my mentor, promising to introduce me to lots of new cameras—his own and the newspaper’s—and to teach me how to take sports pictures, if I was interested. Interested?! It was the most exciting thing an upperclassman had said to me since I had arrived at Exeter two weeks before. Tom wanted someone to cover the sports beat, particularly in the spring when he was hoping to be on the varsity track team and would often be tied up with meets on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons.

Tom taught me to use the Academy’s doubled-lensed, German-made Rolleicord. He explained that, with the Rollei, once I saw the image I wanted framed in the viewfinder I should push the shutter that operated the lower lens to capture the image on film. Tom noted this twin reflex system was excellent for action photos, since the photographer never loses sight of the subject (even a moving one) to the sort of temporary blackout that accompanied the opening and closing of the shutter in a single lens camera. I was excited as my horizon of photographic knowledge expanded.

~

Over the course of spring semester, Tom made a wide selection of cameras available for my use and took time to teach me some of the nuances and idiosyncrasies of each. First among these was the Academy-owned Graflex Speed Graphic, which felt like a tank compared to the Rolleicord I had grown accustomed to wearing around my neck. I had seen the Speed Graphic in movies, witnessed its attached, handheld flash, raised above the head of some fictional newspaper photographer, exploding in the faces of generic gangsters leaving downtown courtrooms. The Graflex’s design—higher resolution film than the Rolleicord, wide angle capabilities, and easy viewing mechanism—meant it was used in a variety of settings for portraits, some sports events, and what Tom called “time-lapsed” still photography.

Mounted on its tripod, the Speed Graphic’s wide angle capabilities were perfect for capturing a shell full of four long-armed prep school boys powering their sleek boat over the Squamscott River, which makes its way through the marshes to the Atlantic Ocean a dozen miles away. In the world of ubiquitous digital photography and disposable cameras that we inhabit nowadays, my excitement at the prospect of using this famed American-designed, large-format machine with its oversized negatives might seem a bit wonky. But that was the late 1950s. And I was over the moon.

~

I never bothered to tell Willie (face to face, or in writing) that I was using some of the finest cameras made in the world. I never sent him a copy of the print of my first photograph that appeared in the school newspaper. I didn’t even tell him when I became the assistant photographic editor or when one of my photos for The Exonian—a shot of four boys in a crew shell—was selected for the yearbook my upper year.

At the time, I blamed my failure as a correspondent on the intensity of my schedule. Chapel attendance was required Monday through Saturday and began at 8:00 a.m. Classes were scheduled between 8:30 a.m. until noon, six days a week. After lunch, a two-hour period was reserved for required sports activities, except Wednesday and Saturday afternoons. Two afternoon class periods started at 4:30 p.m., except Wednesday and Saturdays, although most students only had one afternoon class period, usually the 5:25 slot. (If you were taking fifth year Greek or Latin, you might have a 4:30 class.) Most clubs and extracurricular activities took place after dinner between 7:00 and 8:00 for preps, who had to check in with the teacher on duty in their dormitory by 8:00 every night (unless they had permission from the dormitory faculty or were attending the Saturday night movies in the gym). Church attendance was required on Sunday, except for Jewish students who could

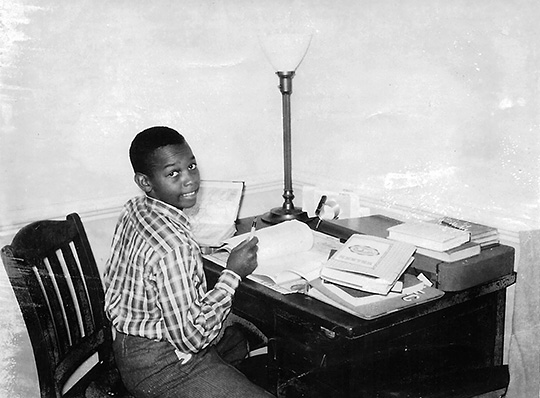

|

|

| Larry I. Palmer Exeter, 1958 Photo by unknown dorm mate |

|

attend their Friday night services.

“Unscheduled time” was a fiction, even though there were no required study periods at Exeter. I had at least one “free” period every morning, Monday through Saturday. I could go downtown, pick up my mail, or stop in the Academy Grille for a cherry coke. I might stop in the Grille one day a week, but if I did not spend most of my “free” time during the morning studying I would not be prepared for my afternoon class or the next day’s classes. The method of instruction in which twelve or so boys and a teacher sat around an oval “Harkness” table to probe the assigned materials encouraged preparation, if for no other reason than to save oneself the embarrassment of being unable to participate if the teacher directed a question at you, or asked you to respond to another student’s comments. The hectic schedule, however, did not stop me from sending an occasional short note to Mom or Cynthia (a girl I knew from grade school back in St. Louis).

|

|

| Larry and Brink 1960 Exeter Yearbook |

|

I would like to think I failed to share stories about my new adventures in photography with Willie because I didn’t want to make him feel bad being stuck back at home with his old Pentax. At the time, I assumed it was the expensive technology alone that made great photographs. I may even have presumed, like any proud, competitive sibling, that my action shots were somehow “better than,” and not simply “different from,” my brother’s still photography. I truly believed that Willie would have been dissatisfied with his 35mm Pentax if he knew I had my hands on Tom’s 35mm Leica or his Rolleiflex, the professional model of the Academy’s Rolleicord. Willie’s lessons in life and photography faded into the shadows along with many other things I left back home. But there was something besides the distance, something in Willie’s attitude and actions toward me that had left me troubled and noncommunicative and made the passions he’d tried to share feel more and more like hand-me-down clothes that didn’t quite fit. Even before I left for Exeter. ![]()