Mountain Lake and the Collaborative Spirit

from The Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop: Art in Locale

All of the Mountain Lake Workshops have had different emphases. Jiro Okura’s were about meditation and the development of intuitive skills through repetitive actions as a kind of “bodily chanting.”

|

| Jiro Okura's Shisendo Garden, Breathing Lines #12, For John Cage, August 12, 1992, blue ink on “smoked” paper, 28 x 72 in. (71.12 x 182.88 cm) painted by Jiro Okura, Ray Kass, Gloria Heath, Rob Cole, Robin Boucher, and Joe Kelley. |

|

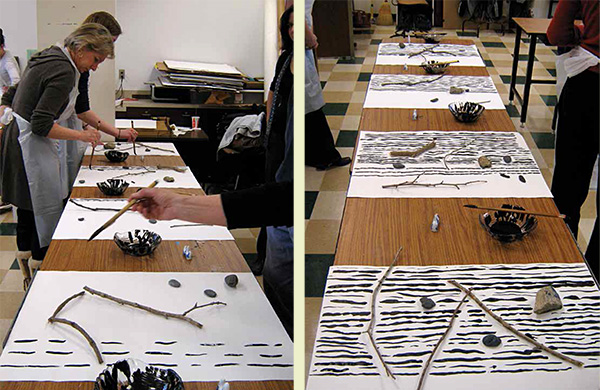

| Workshop participants at the

College of William and Mary, 1993 To adapt Okura’s sumi-e–derived technique to the collaborative workshop process, the notion that “it doesn’t matter who holds the brush” (Finster, 1985) was adopted for this workshop. Members of the community, after rehearsal, painted with Okura using various inks and traditional Japanese brushes on paper. Imitating the artist’s initial vertical brush stroke that changed width in a predictable rhythmic pattern of thick and thin, participants followed each other in painting a “matching” parallel stroke that fit into the pattern of the previous stroke. |

Some involved aspects of narrative as in Howard Finster’s workshop and Joe Kelley’s Appalachian Trail Frieze or a sense of nature at the cosmological level as in John Cage’s workshops.

|

| Life-sized cut-out plywood figures of Howard Finster “dementions”: (L-R) Howard in his Little Dress,

Elvis Presley, Jesus Christ, Howard Finster, Abraham Lincoln, Howard in his Little Dress. |

|

| Joe Kelley and the Mountain Lake Workshop with assistance from Stefan Gibson, Pathways: The Appalachian Trail Frieze, 1994: gallery installation (above); detail (below). |

|

|

| John Cage, Gift (for Jiro Okura) watercolor on “smoked” mulberry paper, 72 x 36 in. (182.88 x 91.44 cm). This painting was a gift to Okura welcoming him to his upcoming Mountain Lake Workshop which immediately followed Cage's workshop in 1990. Photo: Jiro Okura family, Kyoto |

Other workshops also touched on nature and natural forces. Ray Kass, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, and Kathy Pinkerton did so at the microbiological level by looking at microbial organisms, while Jackie Matisse explored natural forces like wind and gravity through the use of new technologies.

|

| Papermaking at the Mountain Lake Workshop with Helen Frederick and Mierle Laderman Ukeles. |

|

|

|

| Jackie Matisse painting kite tails; Francis Thompson in background | Matisse’s kites flying underwater in

Molly Davies’ 1983 video Sea Tails, music by David Tudor |

Despite these differences, what all of the workshops have in common is that they have been similarly structured around the collaborative process and various forms of chance and indeterminacy. These procedures, when combined with visionary themes and “landscape” elements from the microbial to the near grandiose, allow for the reconsideration of the issue of artistic control of the creative process. This is because the very idea of collaboration challenges the generally accepted notion of the artist as someone who works alone, isolated from the wider world. Collaboration shows how groups of individuals working together following mutually agreed-upon procedures can create genuine works of art that reflect a unity of ideas but, in their complexity and scale, as evident in Okura’s Screen Tachi or Matisse’s virtual Kites Flying In and Out of Space, may be beyond the scope and expertise of any single individual.

|

| Jiro Okura, Screen Tachi. |

|

| Silhouette of Jackie

Matisse in Virginia Tech’s virtual reality CAVE™ |

At the same time, such works can still reflect the individual hand and mind through their idiosyncratic details. Moreover, at a more metaphorical level, the collaborative process in which people work together toward a common goal reflects a creative communal “coming together” that in many ways symbolizes the nature of society itself and represents an important psychological “breakthrough” in how we think about our relationship to the world.

When combined with chance and indeterminacy, the collaborative process also offers a way to “let” unintended and unexpected things occur. The unintended and unexpected force the thoughtful viewer to confront the unfamiliar and to rely less on the psychological comfort and security that the already known provides. In this way one is encouraged to examine accepted relationships with things in the world, with normal patterns of “being,” and to see them in a new light so that new concepts can develop that expand our understanding of ourselves as well as the world around us.

This was something that Cage had attempted to do with his music as early as 1952 when he composed 4' 33''. In the premier performance of this piece, often referred to simply as Silence, pianist David Tudor sat quietly before a piano on stage at Woodstock, New York, in late August of 1952 as the unintended and unexpected sounds of both nature and humans (wind in the trees, raindrops on the roof, and the usual audience noises) were allowed to comprise the “music.” In Silence, a book of his lectures and writings published nearly a decade later in 1961, Cage argued that when one realizes that sounds occur whether intended or not, if one then turns to the unintended sounds, this is a psychological turning:

this psychological turning leads to the world of nature, where, gradually or suddenly, one sees that humanity and nature, not separate, are in the world together. . . . 1

1 John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (Middleton, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1973), p. 5.

Something of an analogous “psychological turning” has infused the spirit of the Mountain Lake Workshops, causing nothing less than a re-envisioning of the creative self’s ability to conceptualize and create a deeper image and understanding of nature through a collaborative process that allows for chance and indeterminacy to occur.

As the workshops progressed, it became increasingly clear that the direction in which the collaborative process was going would merge the conception of nature (as envisioned by Coomaraswamy) with the imagery depicted in the work. The visual appearance of the works was now being generated by processes similar to those that the works intended to symbolize. This seems to be the unconscious effect of combining the collaborative process with chance and indeterminacy, of letting things happen that could not have been predicted at the outset of any of the individual workshops.

This re-envisioning of the artistic/creative self that precipitated toward this deeper image and conception of nature also had connections to the social, economic, and political issues that the ecology movement (e.g., Save the Planet) has made visible. In some respects this was the direct result of one of the motivational impulses of the Mountain Lake programs in their desire to respond to the broader social and political climate of Late Modern and Postmodern society. As German philosopher Jurgen Habermas has observed, Postmodern society needs to develop a system of values that extends beyond the purely economic and entrepreneurial. “The life-world,” he argues,

has to become able to develop institutions out of itself which set limits to the internal dynamics and imperatives of an almost autonomous economic system and its administrative compliments. 2

2 Jurgen Habermas, "Modernity Versus Postmodernity," New German Critique 22 (Winter, 1981), reprinted in Howard Risatti, Postmodern Perspectives: Issues in Contemporary Art (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1990), p. 64.

Unease over various social and political issues (e.g., the environment, race, healthcare, gender identity) which today seem to intrude into our attention at every moment is evidence that attempts are being made to do just this. However, this climate of unease also betrays the very real difficulties involved in achieving these goals even today in the first decades of the new millennium.

Looking back it becomes clear that the imperatives of early-twentieth-century modern society were intimately linked to economic transformation because, in many ways, economic progress and social progress were thought to be synonymous, to be inextricably linked. American prosperity as well as the persistent Marxist experiments over the century are evidence of this and help explain why the modernist avant-garde waged such a heated battle in the cultural realm against what can be called “the authority of tradition.” In the heady early days of Modernism, it was believed that the meaning and value of social goals could be determined and measured by — even equated with — economic values. In such a climate, the transformative values of Modernism were economic and transcendent at one and the same time.

Today this equation no longer seems valid as economic interests seem to prevail over all other interests and values. As economic inequality increases, the economic system of late capitalism, which is transforming life relationships at every level, from the social to the environmental, has become an almost autonomous, self-justifying system in which higher, non–economically equatable goals seem devalued and increasingly difficult to defend; hence attacks on the humanities and liberal arts. As political economist Daniel Bell noted, already in 1978, in late capitalist society

emphasis on accumulation [of wealth] has made that activity an end in itself . . . [rather than] a means to the realization of virtue, a means of leading a civilized life. 3

3 Daniel Bell, “Modernism and Capitalism,” Partisan Review, vol. XLV, no. 2, 1978, p. 207. Perhaps this is why curators Neal Benezra and Olga M. Viso use the term “distemper” to allude to what they see as a “climate of unease in which a sense of anxiety and disaffection permeates the age.” See Distemper: Dissonant Themes in the Art of the 1990s, 1996 exhibition catalogue, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, a Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., distributed by Art Publishers, New York.

Seen from this perspective, it is clear that from the very beginning the topics that the Mountain Lake Symposium addressed and that are reflected in the Mountain Lake Workshops, topics about “aesthetics and morality,” “art and society,” and “art and conscience,” were, in a subtle way, radically subversive and ahead of their time because they were never about how to flourish in art’s economic realm (i.e., how to make money). And when participants were invited to the symposium programs, it became clear again and again that their willingness to participate was predicated on the seriousness and relevance of the topics under discussion as well as their respect for the ideas of the other participants. 4 As a result, a spirit of collaboration also developed in the programs as audience and speakers came together in a friendly exchange of ideas in an effort to make sense of the world.

4 It is interesting that over the years, only two of the numerous prospective participants I contacted about possibly speaking at the symposium inquired about remuneration. Ironically, both were neo-Marxist art critics.

Even addressing the narrower realm of art making itself, the symposium programs were clearly intended to engage larger cultural issues and values that went well beyond those of a late Modernist formalism and “stylistic competence”— Kuspit’s idea of the “good enough artist” or the “aesthetic management” of form. But they should not be seen as an attempt to establish and promote a regional and local style in contemporary art. What the symposium and workshops attempted to frame and address is a very critical and pertinent question for art and one of increasing relevance today: What is or should be the role of art in society today?

|

| John Cage (center) assisted inside the framework of a 56 inch wide custom-made brush |

This crucial question underlying all the Mountain Lake programs was developed as a context for art in the symposium through theoretical and critical discussions. It was then extended to the workshops as the philosophical rationale for their focus on “artists and locale” and “region and place.” Because of this critical context, it would be mistaken to see the workshops as attacks on a New York art world that, for many people, has come to represent the economic mainstream and urban culture. Instead, the workshops should be understood as attempts to approach the question of art’s role in society from a local level, from a level of experience that is as unmediated as possible — i.e., something as direct as the gathering of rocks by a river or the blessing and harvesting of trees in the woods. That the workshops demanded a high degree of competence and innovation in the manipulation of such materials showed that an art coming out of such an experience need not be intellectually or aesthetically retardataire, that such an art could be as good as the best of mainstream art.

When seen in this perspective, the workshops are, in a sense, “demonstration events” encouraging both artists and participants to seek ways to make a meaningful art out of their direct, localized experiences. Such experiences could well form the basis of a local/regional self which possesses a deeper psychological conception of place and environment, one based on real experiences untethered to the commercialism of mass culture.

This, the Mountain Lake “model” of the local/regional self, is based on a psychological turning or transformation in which the individual, in paying attention to his or her immediate environment, gains a new and deeper awareness of self and the idea of place. And because of its psychological basis, such a self is not bound by or limited to a particular place or a specific geographic region. In this sense it can develop just as easily in New York City as in the rural landscape of Appalachia.

|

| Giles County Virginia. |

Because the art from the workshops is related to such a self, it is not an art that militates against the idea of a mainstream urban culture, but one that has attempted to realize itself parallel to and in harmony with a spirit of culture based on shared values that are not purely economic. Moreover, rather than uncritically accept the notion that an art, to be contemporary, must be intentionally and consciously avant-garde, the approach of the workshops is that art should stem from an informed and informing cultural activity in which shared meanings and values are created through collaborative experience of place and the art-making process. In this sense, the Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshops articulate what could be seen as a post avant-garde conception of art.

Through their emphasis on collaboration and chance, the Mountain Lake programs have attempted to open and explore a pathway to give the individual and collective imagination the potential to realize a meaningful and socially responsible relationship to the world around it through the aesthetic experience. It is in this way that the programs of the Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop attempt to situate art within a larger realm of culture, a realm of culture that is cognizant of the social context in which art must exist in order for it to provide a meaningful experience for both makers and viewers. ![]()