print preview

print previewKing of Postcards: On Aleš Debeljak

To have a friend, to look at him, to follow him with your eyes, to admire him in friendship, is to know in a more intense way, already injured, always insistent, and more and more unforgettable, that one of the two of you will inevitably see the other die. One of us, each says to himself, the day will come when one of the two of us will see himself no longer seeing the other and so will carry the other within him a while longer . . .

—Jacques Derrida, The Work of Mourning

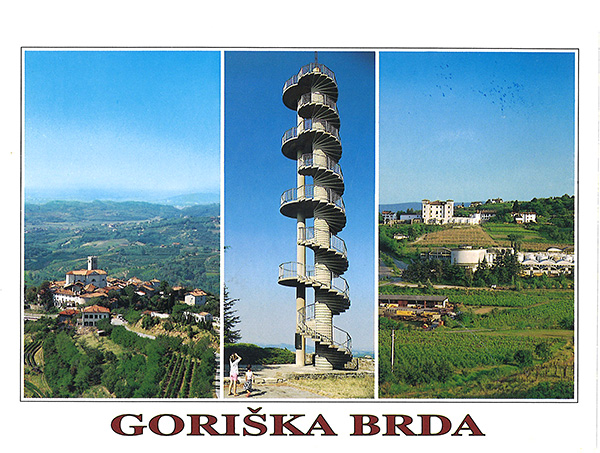

Several winters ago, for no reason whatsoever, I fell temporarily out of touch with Aleš. It wasn’t the first time I’d gone AWOL in a decade and a half of knowing him—a few years earlier, he’d addressed me as “my long-not-heard-from-soulmate”—and it wouldn’t be the last. Then an envelope arrived one day, its contents placing in stark relief my fickle trickle of emails, phone calls, and letters. “My man,” he wrote characteristically, on a postcard displaying Goriška Brda, “with a recently discovered sheaf of stamps, you’ll have to use them—not all of them necessary on postcards to me!” Here was a tangible measure, not that I needed any, of the absolutely exorbitant nature of Aleš’s friendship. Had he really just found a hodgepodge of postage, squirreled away somewhere, or had he gone out expressly to buy the stamps? I felt alternating levels of pressure and shame, as I imagine Emily Dickinson’s slowpoke correspondents sometimes had. Not least when, earlier that fall, Aleš had already sent me the printout of an email message to which I’d apparently failed to reply. I’m relieved to say I used those supposedly secondhand stamps up long ago—or nearly. A last, crinkled ribbon of four cent stamps, depicting a Chippendale chair, is still on my desk.

|

|

~

“A few days ago, I was in Zagreb (lecture),” he reported in fall 2015, “today, it’s a festival in Rovinj. In and out, that’s the spiel!” I loved his facility—check that: felicity—using American vernacular, which he scattered across his missives with a flair matched only by the breadth of his repertoire. Moolah, traipsing, lollygag, yuck! To boot, to a tilt, semester kicks in, time to kick-start a new book, no kidding, breeze in and blow out. Without an agenda, pick up the tab, “our Zvezna 41 nest is getting emptier,” good vibes. Sometimes I couldn’t tell whether his variations were slips of the tongue or tongue-in-cheek innovations. More than a decade after the Dnevi poezije in vina (“days of poetry and wine”) festival in Medana, Aleš would lament he “can’t believe that so much wine has flown,” an entirely fitting, mix-and-match phrase to describe a long-ago literary event cosponsored by the region’s major vintners. His wryly revised clichés were themselves what he called, in a different context, a “new take on the old tunes.”

~

Aleš’s belief in the value of balancing ancient and modern, nuanced throughout his critical writings in terms of culture and global citizenship, constituted a persistent theme in his postcards. “Here, may this contemporary revival,” he wrote to me and my wife Sandrine, on a card of Prešeren Square from above, “serve as a reminder of our shared new-world / old-world love ties and those of friendship!”

This dynamic of reviving the past must’ve been particularly on his mind in ’07, for just before that card I’d received another, a photo of two bark mushrooms in the shape of outsized snails: “primeval forest, old growth,” he said, “but look at the bold shapes and hopeful forms!” It’s only now, with all his cards stacked in front of me, in a top-heavy, scale model Triglav effect, that I realize how much consolation my contemplative pal found in nature. “Economic crisis contributes to the general slump,” he complained, in November 2012, “but the natural world remains enchanting.” Three years later, when things had worsened, “Out here, only nature holds out a promise / otherwise—economically speaking,” he fretted, “my country is again becoming a poor periphery.” The baldness of his outdoorsy assertions still takes me off guard. “I love the feel of snow,” he yelped from a ski slope, where the “alpine sublime,” a bit later, in spring, was exemplified by blooming daffodils. Or else, “It’s kitsch but I love it,” he confessed from the coast, getting a little carried away in the heat: “lavender, flat rocks, burning sun, deep blue-green silk of sea, a sailing boat in a distance!” I wish him exactly such serenity now, “lazily” smoking, with sunglasses on, cuing up the next tacky card in the queue. “Melancholy & smiling.”

~

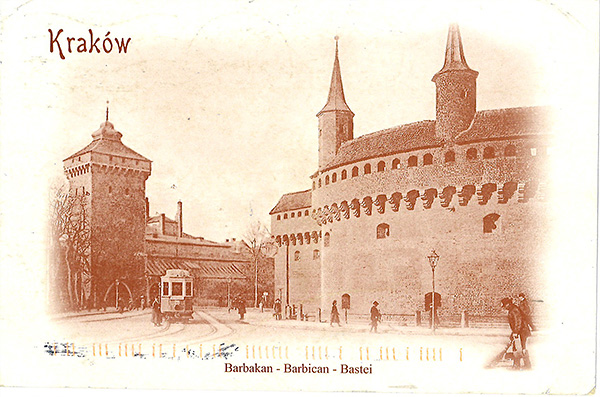

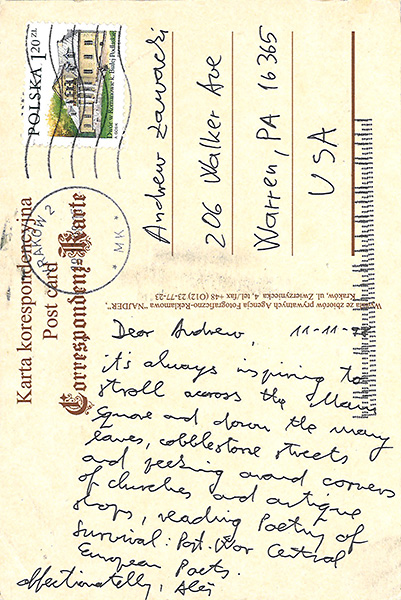

Cards came from cities all across Europe. From Edinburgh, “doorstep to white nights,” and from the “Nordic outpost” of Cøpenhagen. From Stockholm, “well-organized and pleasant: indoors, that is.” From Budapest, “another adopted city of mine,” as well as Bucharest, where the hotel featured “blessed AC,” before he went “off to the Black Sea, in the footsteps of Ovidius!” From a “swanky hotel” in the German capital, which Aleš dubbed “el splendido!” as if lurking behind Berlin were another warmer, less orderly, favorite city, Barcelona. Attuned to cultural and geographical drift, a card from Dublin quotes Lorca’s “green how I love you green,” quipping that the line “could easily have been an Irish verse.” From Vilnius, “a pagan land of thick forests and generous soul and pagan stories and,” continuing the theme of rented lodgings, “bad plumbing in hotels.” Traversing Sarajevo, Mostar, and Dubrovnik was a “Yugo-nostalgia trip,” while an 11-11-98 card from pre-EU Kraków features a 1.20 ZL stamp which—about to travel to Poland myself—I suddenly find very exotic.

|

|

At various periods Aleš had regular teaching and talking gigs and prize committee junkets in Warsaw, Vienna, Cetinje, Podgorica (to decide “a big little award”). Cards from coastal Veli Lošinj, “lovely place,” were de rigueur in late summer. From the Cinque Terre, where my wife and I had just spent a month, he wrote to say that he and his wife, Erica, were “retracing Andrew & Sandrine’s footsteps VIA AMORE.” Nor was travel to foreign cities a purely personal matter, even if, invoking “deceptions of cosmopolitanism that I love to indulge,” Aleš liked pretending to “feel DEBEST as bourgeois bohemian,” as slacker-smoker-caffeinehead-flâneur. “Every city and town looks better when observed over the shoulders of history,” he asserted, loyal to the long view: “Belgrade is no exception.” His most profound statement of peripeteia came from Arches National Park in Utah, in my native country: “my pal, one has to come to the American shores to become aware of one’s ‘European’ identity.”

~

Awash with innuendos of dillydallying, one card, written on a Friday—the only one in the entire bunch that specifies the day of the week—has an asterisk to highlight the glib squib, “other people work!” But the self-styled boho hobo was a workaholic, of course, and only a vaguely convincing stoner with nothing better to do today and nowhere else to be, despite his full-time university job and a deadline to meet at the country’s major paper. “The postcard’s here to confuse the class enemy,” he kidded from Piran, “but I’m in Piran all right.”

~

Aleš included his email address on a card he sent me from Sweden in ’98. We had to have been using email before then, no? Maybe his @ddress had just changed. Or I hadn’t been using it often enough. Or maybe, a self-proclaimed Luddite and partisan of “paperology”—his term, a terrific one—Aleš had merely capitulated late to the medium, as he would with the fax and with Skype. He was relatively quick to move to a cell phone, and compact discs he could do, and did. One CD he sent, “old media with even older content,” touched us despite being cracked in transit, for it featured multilingual children’s songs, recorded by buddies of his. He never got around to the BlackBerry or tablet, let alone i-anything, though in 2014 (since it’s never too late) he mentioned he’d gotten a text—from his mother! Auditioning this newfangled, hipper persona, while ensuring the union of function and form, he referred to the incoming memo as a “txtmssge.” (This reminded me, in turn, of that infamous article from The Onion, which reported that President Clinton would be deploying thousands of vowels to the war-torn Balkans.)

Technology was an enduring aura around our writing to one another, and a source of humor and irony as well, beginning with the antiquated quaintness of postcards, period, which Aleš once likened to “sending smoke signals (priceless, haha).” Earlier that same year, a card had accompanied a mini-cassette. “Can you rescue this tape,” he asked, as if filing a telegram. “It’s finished, over, kaput, can’t play it. Has my interview with you on it. Technical expert says the recorder speed was too slow.” Unable to salvage the contents, we redid the Q&A by letter, then finished it over the ether.

Aleš admired people who could navigate tech, including knowing when to put it aside. “Three days of hiking around Seven Lakes Valley below Mt. Triglav!” he declared, before praising his family: “Am so proud of my town-bound gadget handlers!” A tenacious language smuggler, Aleš found quiet lyricism in the enigmatic lingo of a techno he rarely conquered in real life. “After July 15,” he reported, while finishing an essay collection, “I’ll be offline for ∞.” While avoiding digital distractions was a suspended state of “fully tourist grace” synonymous with being “offduty,” like a beach bum or skate punk or “hedonist,” say—“hands in pockets,” “idle and whistling”—going incommunicado also served as a necessary condition for engaging the work of imagination. Greetings “from offlineland,” he popped up to say, while ensconced in his “Piran retreat,” sketching what would become Kako postati človek, his final poetry book.

|

|

~

To this day I dig the ingenuity of his fricative neologism, “offphone.” The adverb haunts me to no small degree because the last time I heard his voice, in autumn ’15, Aleš had recorded a message from New Haven, in a phone tag match we played over several days. I remember fielding it first in a parking garage, or maybe the Kroger lot—I forget. He’d overslept my scheduled call to the landline where he was staying and sounded groggy, maybe annoyed at himself. I swapped out that phone a year ago, so his voicemail, too, is now lost.

~

“Dear pal,” he’d written from Valencia, on October 25, 2007—as if anticipating by four years the advent of Game of Thrones, which he and Erica binge-watched with friends—“after a game of phones, postcards remain reliable, haha.”

~

In his wake, Aleš dragged with him the entire world—I practically see it in sepia now—of meandering down my drive to check the mail. Already the site of an obsolete art when Aleš had been slinging me cards, which were all the more precious for carrying the epoch of par avion on their 7g backs, the mailbox has no meaning since he left. “This is the first appeasement, when I am without you . . . ” Derrida wrote in The Post Card, about learning the carrier route:

. . . and in order really to feel what I am talking about, I mean about my body, you must recall what an American mailbox standing in the street is like, how one opens it, how the pickups are indicated, and the form and the weight of that oblique cover that you pull toward yourself at the last moment (110).

From Chicago to Melbourne, St. Andrews to New York, Paris to Warren, PA, Aleš’s postcards landed in myriad letter boxes and pigeonholes, on tattered welcome mats. Or else the voyaging roles were reversed, and a card that arrived ahead of me, when I’d been out of town, was waiting there when I let myself in, like it hadn’t gotten off the couch in days. Once in a while my parents had to hand-deliver me a postcard which, weeks or even months before, had fallen through the grad-school cracks of one ad hoc apartment and the next.

On Aleš’s nomadic end as well, a sluggish postcard of mine would periodically need forwarding. Sometimes we’d realize the error and discuss the card and its contents over the phone, before the hard copy landed, by that point just a written confirmation of our call. Other times a card must’ve shown up as a belated, even anachronistic surprise. The Work of Mourning again: “He wasn’t there any longer, something I didn’t yet know,” Derrida recounted, at a memorial service for Joseph Riddel, recalling a letter he’d sent many years earlier to his friend, whose address turned out to be no longer valid. “Already he wasn’t there any more.”

~

But it’s not true, what I said about meaninglessness. That’s just how it felt at first, for a while. The black metal box on its modest crossarm, angled at the end of my yard, is a cenotaph. I don’t go to grab my mail, although that happens. I walk there, daily, to whisper a few words to my faraway friend, to listen to the silence trapped behind the tinny door.

~

Once he claimed to have driven out to the marshes, where “I levitate,” he boasted almost credibly, “among the frozen reeds!!”

~

Curious in extremis, an inveterate intellectual with a quick, encyclopedic mind, Aleško—as his family would call him, a funny diminutive for a father of three—couldn’t help acting the unreformed schoolboy, the kid who knew all kinds of footnoted shit. As a postscript to an otherwise strictly business card about signing a limited edition, “This flower (over),” he directed me, indicating a Black Alpine Vanilla Orchid, was an “endangered species, endemic to the Alps.” Who knew? And who knew that he knew?

|

|

~

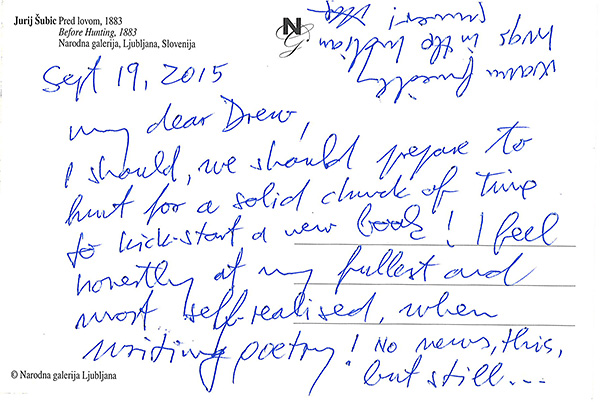

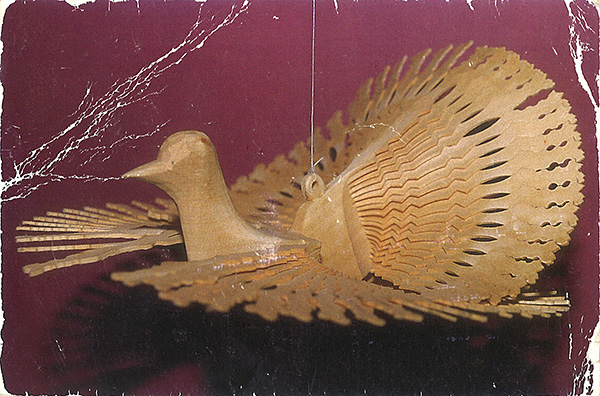

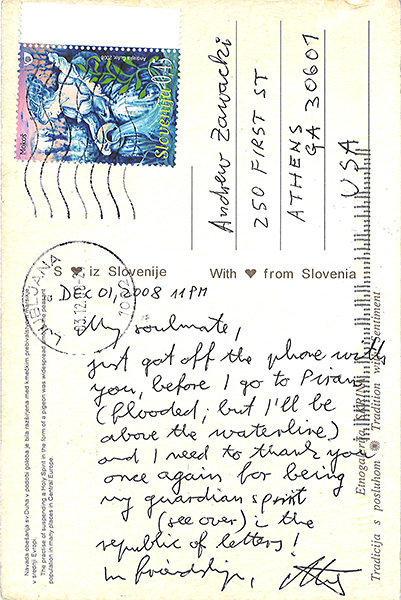

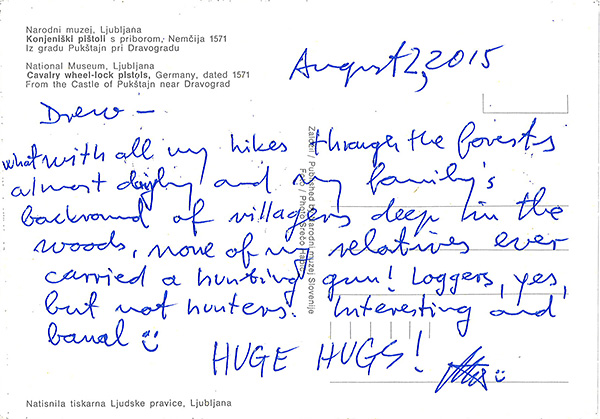

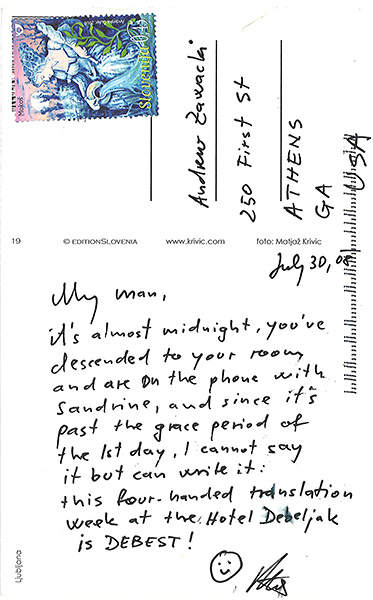

Aleš frequently nodded to the image like that, finding in a card’s pictorial motif a sideways motive for writing. A woman riding a Lohner moped, in 1949—touting “good, old times before our time!”—served as a clever excuse to salute the future, by congratulating us on our second daughter, hoping we might “continue in good spirits with extra spring in [our] soles and souls.” At 11 p.m. one early December, having just put down the phone with me, he thanked me “for being my guardian spirit (see over) in the republic of letters.” The pictorial side shows a suspended pigeon ornament, a peasant tradition venerating the Holy Spirit. Keeping with that rustic nostalgija, another card presents a pair of cavalry wheel lock pistols from the sixteenth century. “What with all my hikes through the forests almost daily and my family’s background of villagers deep in the woods,” Aleš informed me, “none of my relatives ever carried a hunting gun! Loggers, yes, but not hunters. Interesting and banal.” Such odd, evocative, ekphrastic exercises could easily become invitations, gestures of hospitality. “Turn this card over,” he guided me one August, “and you’ll see what we see from the terrace of a summer house that belongs to our friends—.” And what is it you see now, on some other side, tell me the lyrics of your song, I want to sing with you.

|

|

~

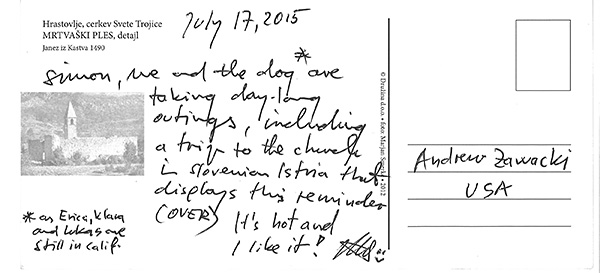

He wrote from home to say he and his son Simon had been walking the dog. The rest of the family was in San Francisco. The card, he noted, issued from a “church in Slovenian Istria that displays this reminder (OVER).” The verso showed a detail of a 1490 tableau illustrating, in stop-motion fashion, the human march from infancy to death. It was dated six months before he died, so I can’t help reading that reminder as a portent.

|

|

~

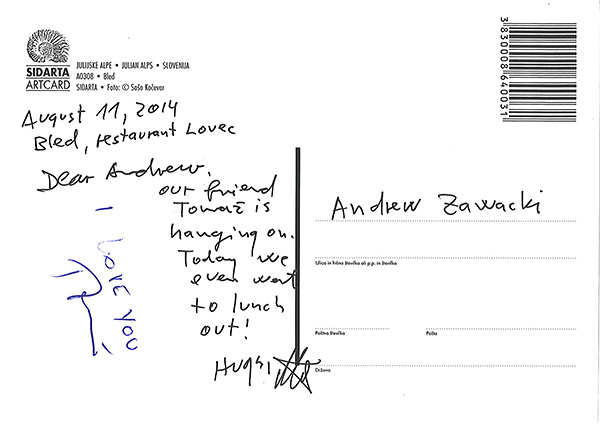

“Tomaž would have turned 74 today,” Aleš had written two weeks earlier, on July 4, months after the death of Šalamun, our mutual friend. “Despite the past tense, he’s with us still.” I was glad to help shoulder Aleš’s sorrow and to know he had written to lighten my own. Indeed, the most moving card he ever sent me, as Tomaž was nearing the end, had been signed by Slovenia’s two greatest living poets. They’d just had lunch together at the restaurant Lovec in Bled. “The name is made to do without the life of the bearer,” Derrida claimed, “and is therefore always somewhat the name of someone dead” (39).

|

|

~

This card from Kras is a perfect haiku: “The springtime has ar- / rived in full bloom and I ex- / plore the country roads!” (line breaks mine). Ditto one evoking the sublime that he sent after dropping his family at the Trieste airport for their annual trip to Cali: “I made a stop at / Duino and contem= plated / beauty and terror.” Another exceeds the syllable count by just one, and the topic sounds about right—“Setting out to me- / ditate on the meaning of / willows and the body”—while this, from Split, is haikulike, at 5-7-3: “My soulmate, ferries / sail by, southbound, and my path / leads back north . . . ” Maybe he left those two final feet off on purpose, to clear space for his own feet, which he knew he’d need someday, for walking north.

~

Often, I’d try to compensate for the relative paucity of my outgoing cards by trying to squeeze more on. That allayed a little guilt, as if it were word count that counted. Once I got all psyched up and devised a project: during a translation residence in southern France, in June 2014, I bought thirty colored Van Gogh cards, resolved to send one a day. While Aleš later wrote to thank me for the “Vincent gallery” he’d assembled on the fridge, elegantly returning the volley with a Bedroom at Arles of his own, I never managed to use all the cards I’d stashed.

~

Pin holes in some of the earliest—’98, ’99—tell me I must’ve tacked them up.

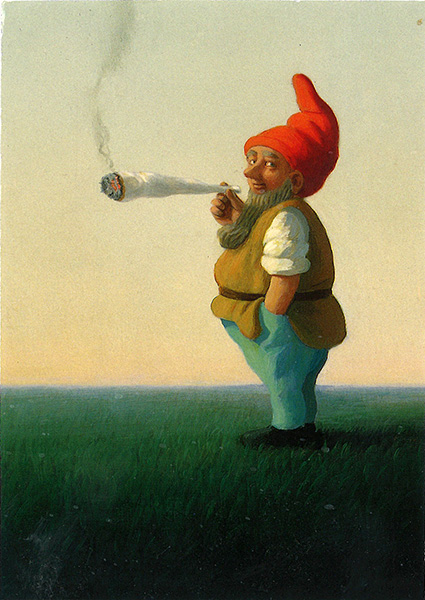

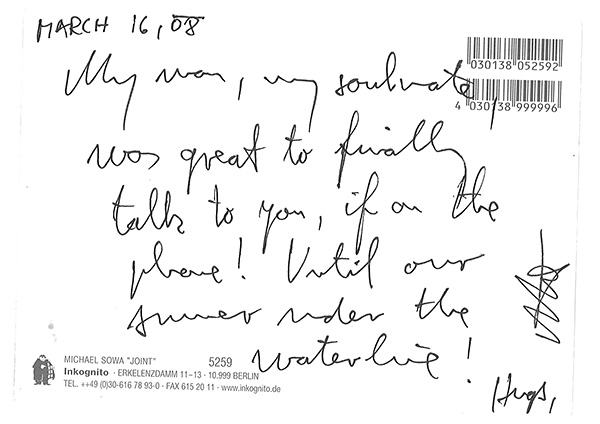

The one that stayed longest on the fridge, however, is a German card featuring surrealist Michael Sowa’s whimsical painting “Joint-Zwerg,” dwarf with joint. Nearly half the height of the happily stoned, bearded homunculus, the spliff seems rolled of the same supple fabric as his cap, whose orange is recapitulated in the doobie’s papery embers. Every time it caught our eye, Sandrine and I laughed out loud.

|

|

~

With a charming, romantic reverence for even minor milestones, Aleš would rarely neglect to honor an important date—or even christen one—with a postcard. In the middle of a Santa Cruz job negotiation on my end, and apparently en route to the West coast himself at that moment, Aleš wrote, “So, the king of postcards wants to beat your move to CA!” An April 27 card from Tivoli commemorated the Liberation Front, while in June ’09 he noted that Bill Clinton was in Slovenia. Weaving the historical and personal, on Tito’s birthday, May 25, mentioning the Day of Youth, he wished our daughter Ella (5/24) happy birthday. Similarly, on a card of Robert Capa’s celebrated photo depicting civilians in Normandy welcoming American troops in ’44, he waxed grandiose: “Dear friends, may your love, your American-French love, last forever!” When he sent me a card on the fifteenth anniversary of his wedding, I regretted not having sent a card to him and Erica instead—but was also proud to be included in his capacious happiness. By spring 2010, when I earned my PhD, I might well have predicted his epistolary toast, “Here’s to you, DOCTOR ZAWACKI!” On the other hand, I confess to having been caught unawares—and very deeply moved—when he sent a thoughtful note of “healing & inspiration” soon after I wrecked my bike (and my back and neck). If one, typically autumnal card had him “chasing the last days of skiing season,” coddled in “suspended time,” another startled me with its uncharacteristic tribute to what begins: “swimming season,” he announced from Dalmatia, “is now officially opened.”

I’d know him to write on anniversaries that made him “melancholy,” a word he employed nearly as often as “grace” and “madness” (the former attended the waning weeks of summer, before fall semester would usher the latter back in). “Time is a truly mysterious substance,” he mused, as Simon turned sixteen. When his eldest, Klara, finished high school, “Can’t quite get it!” he admitted, and when she left for Charles University: “I long to be in her shoes.” Such sentiments jump out at me suddenly, shuffling through the archive of his off-the-cuff confessions. It hadn’t been that long, seemingly, since he’d reported “taking lessons in the elusive art of patience” with his children, on the coast one summer right before the turn of the millennium: coloring with Klara, “pouring seawater in and out of pots with Simon,” cuddling Lukas the youngest. Aleš was temperamentally steadfast in keeping vigil with the passage of time. “Where did all those years go?!” he asked, a decade later, “where’s my young soulmate, my younger self?”

~

There were cards thanking me for translating his work, a thank-you for having paid for a meal at Veselka in the East Village, even an afterthought jotted to acknowledge the card I’d sent from Mali. A week before my arrival in Ljubljana, in anticipation of a translation session together, his postcard escorted a black and red T-shirt commemorating modernist literary titan Oton Župančič. Who else down here in podunk Georgia, I remember thinking, pretentiously, can wear clothing flush with three hačeks and a Z? (I once wrote Aleš a postcard at Vogel State Park, where car trouble kept me from leaving my camp. I thought to myself: so, he sends me word from the Adriatic, I send him regards from Deliverance land.) Perhaps no occasion for straddling the secular and sacred rivaled the publication of a new book. He took my Anabranch to the salt flats and wrote to say so. Imagining him out there, a lone reader in a lonely landscape, squinting into the arid sun, was all the audience I wanted. Years later, in thanking me—on a chintzy Ingold Airlines card—for sending my Videotape, he fractured his message with jagged lines and words divided in half, mimicking—or playfully mocking—the poems in that book.

~

To make a hyphen, Aleš would use what looked like an equal sign, as if words partitioned across a margin needed double the ligature. Is that Slovenian convention, or was it his eccentric orthography? Other handwriting quirks I came to cherish for their specificity or quasi-comical air. Liberal with exclamation marks, Aleš shaped his out of a skinny isosceles triangle, the dot at bottom suggesting a bubble. More hilarious and disarming were the cutesy little smiley faces he added to loads of cards, years before the emoji was coined, as if signing a pre-K valentine, or marking an exam deserving of an A+. Some faces featured glasses and wisps of hair; one is jack-o’-lantern-esque; one has sprouted from the card company logo. The year, as he wrote it, was reduced to its last two digits, under a macron. His hallmark “haha” would morph into “hola,” or “halo.” My familiarity with his distinct way of penning “W”—a pair of v’s overlapping in the center, so the letter featured three vertices, not just two—made me feel I had private access to the author (not least because I have “w” in my first and last name both). The “n” in “in” was constantly missing, while the “m” in “I’m” frequently flattened out to an underscore—his identity a blank for his correspondent to fill. His signature was a cardiogram, wild style on the laminated wall.

|

|

~

He almost always signed off, “Hugs!” Occasionally with “Love,” or “warmly,” or “HUGE HUGS!” Once, “SALTY HUGS,” “Hugs across the ocean!” His arms were that transatlantically open, and for a small guy he could really crush you with his embrace (all that judo growing up). In my favorite closing he ventured, “Hugs & slap on the back! Yours,”

~

The most enigmatic of his cards, from Friuli, on February 22, 2009, assumes in retrospect a sinister cast. “If it weren’t for skiing, life would have been less enjoyable,” he wrote. I fixate, of course, on the conditional perfect tense. “Snow poems and lonely poles sticking out of avalanches,” he went on, a little surreal, “is this next? Vederemo.” The last phrase, if I’m making it out correctly, means: let’s see, we’ll soon find out.

~

Anchoring the entire support, licked and stuck in the uppermost right, the stamps are a serrated, chromatic scale—menagerie, flowers, historical figures—and a conjugation of increasing prices, inked with a Pošta Slovenije trumpet ripped from The Crying of Lot 49.

~

The postcard was no mere medium, among so many others, for keeping in touch. Aleš had the kind of rich, gravid, talismanic relationship with postcards that Proust developed with trains, for example, or that bird-watchers have with pelotons in the sky. “When I was here . . . in the spring,” he observed one July in Montenegro, speaking with a seasonal precision appropriate to avian migration, meteorology, or crops, “there were no postcards at kiosks. They only arrived with the summer.”

While her late husband sent cards year-round, Erica confirms that he was most prolific in summer, on holiday at the seaside, where the “entire process connected to the selecting and buying, addressing and writing, stamping and sending of postcards,” she explains, “formed the refrain of our family life” (221). Indeed, among the most humorous passages—for me anyway, who rarely saw the phenomenon live—in her poignant, compelling, beautiful text on Aleš and postcards, “Just Passing Through,” are those describing my friend’s elaborate, unvarying postcard routine. Regardless of how idyllic and placid the setting, and despite the laissez-faire affect with which Aleš imbued his cards, “make no mistake,” Erica says, “this was no passing caprice to send out a few casual greetings from a foreign land. This was industry, mass production, a one-man assembly line” (222). From his “ecumenical” selection methods, which balanced “high-volume output” and “a range of motifs” against “relatively low costs on the raw materials,” to the addressing of each card, which implicated a pair of archaic, dilapidated address books—one for local contacts, the other international—Aleš was clearly on a mission. Starting in on the cards on day one, at a café where his coffee had already gone cold, he thereafter “carried his pen and the stack of unwritten postcards everywhere he went,” Erica recalls, tending to the hefty deck throughout the week (223). In spite of sizable unit inventory and the acrid taste of stamps, he never capitulated to a sponge, insisting on licking his communiqués himself. Ironically, the one step that would inevitably creep up on Aleš was the last: distribution. He’d invariably have to quarterback scramble—calmly, while his family was freaking out—to find a PO before the revving ferry debarked. Failing that, he’d cue up his big smile and booming voice (no one sweet-talked sweeter than ad) to charm some incredulous gas station attendant (with a little cash incentive) into dispatching the precious cargo—fruits of a weeklong, circadian labor of love (224–225).

~

Although I never heard Aleš mention him, his most prolific rival in this obsessive, borderline fetishistic habit was probably On Kawara, whose conceptual work I Got Up involved sending two postcards a day from 1968 through ’79. Tallying some 4,160 pages (about the heft of À la recherche du temps perdu), the Japanese artist’s project, however, featured strict, daily time-stamping rather than aleatory, handwritten messages. And whereas he choreographed the undertaking as a protracted performance, Aleš relaxed his literary ambitions when dashing off cards. Their reverence for the postcard, as a passion for the exacting connoisseur, was manifestly shared, but each participated quite differently in this most commonplace of pastimes.

~

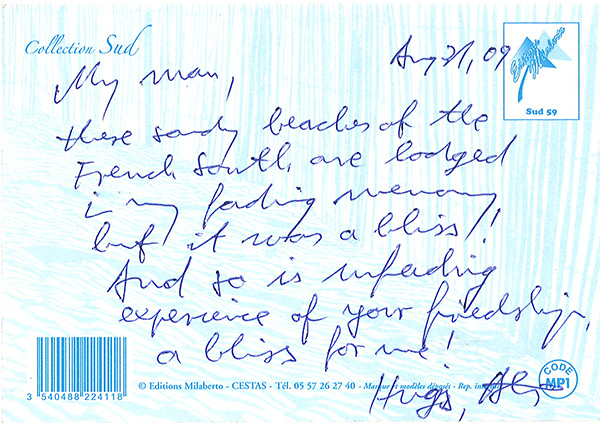

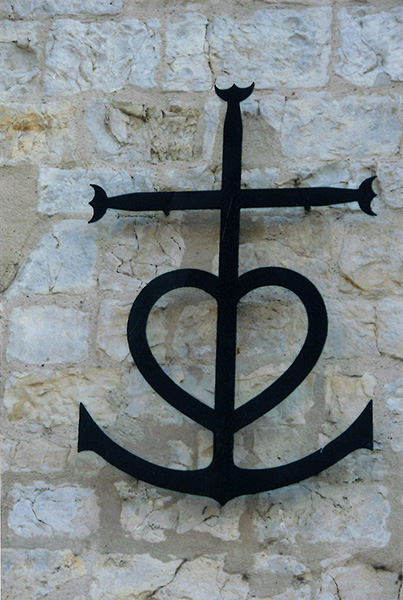

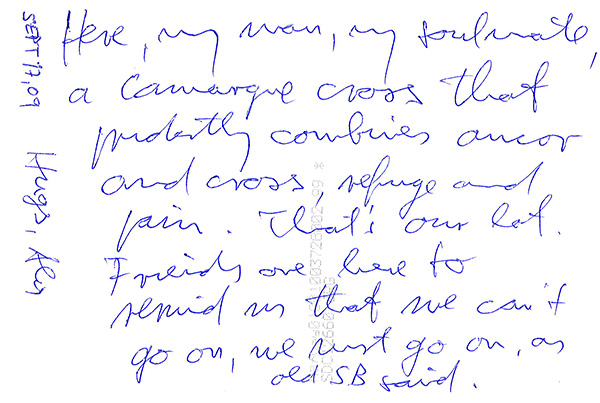

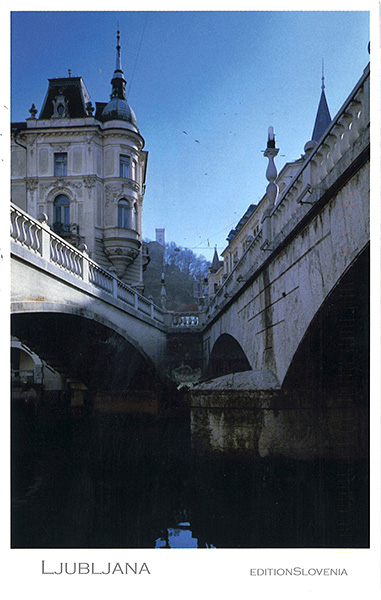

Aleš privileged no discernible postcard format or style, though the companies he patronized most, for local cards at least, were Sidarta Artcard, EditionSlovenia, and Prezlc d.o.o. Matte or glossy, urban or bosky, subaqueous or straight from the street, wide-angle or split-screen, night shot or dawn, “SLO & CRO” Art Deco or mint vintage montage—Aleš was a discriminating but multifarious, promiscuous hoarder. A Zagreb card has the shape of an open umbrella. Several feature perforated edges, probably torn from a booklet, while others would arrive as a minipack, collected inside an envelope, if he’d scribbled them too quickly to post à la carte. One from the Camargue, it hits me now, is actually a color photograph, printed on flimsy quick-lab stock and quoting Beckett on (not) going on. The cards could be run of the mill or museum-official, or utter non sequiturs, or hinting at a juvenile joke. A satirizer of his own penchant for shoegazing, Aleš wrote from Sarajevo, on the reproduction of a painting showing a peasant paring his nails, “From the navel of the Balkans.” One time, on the inner liner of an envelope, he scratched, “Instead of a card from Budapest,” and enclosed a 100-forint note, Attila József’s mustachioed mug reprised in the silly, stick-figure noggin appended to the top fold by the sender. As for the elongated, aerial view of Slovenia’s capital: I only ever once received the same card twice.

|

|

~

The last time I saw Aleš, in Vienna, in summer 2013, we took city bikes to Berggasse 19, to visit where Freud had lived and worked for nearly fifty years. According to Derrida, the “entire post card ontology” is organized according to the Freudian paradigm of fort/da, or “go” and “come” (22). I feel instinctually that yes, our sending postcards back and forth, anticipating their return, was a game we played, Aleš and I, like the child in Freud’s famous anecdote, whose pleasure resided in sheer repetition, as a setup for surprise, throwing away a household object precisely to bring it back—before doing the whole thing again. By staging the exit and advent of objects by himself, the boy, as explained in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, was learning to deal with the pain of his mother’s going out: “her departure had to be enacted, as a necessary preliminary to her joyful return” (14–15). Is that, then, what we were doing, my man, with our postcards over the ocean, mastering one another’s disappearance? Because if so, it sure the fuck didn’t prepare me for this, this crater the size of an earth falling through, and here I still am—one year, seven months, eleven days later—unable to wholly “allow” you to “go away without protesting.” And if the toddler in the tale his grandfather told, “overpowered by the experience” of loss, eventually “took on an active part,” converting his passive witnessing into a gauntlet he trained himself to run and finally delight in, for me it feels like the other way around.

~

Askew between cities or continents, our postcards rarely relayed a conversation. Given gaps in geography, time delays, and our discretely patterned lives, our cards didn’t really answer one another, at least not in any sequential arc, so much as veer apart, waltz to catch up, keep on starting over. They were centrifugal gifts, flying in every direction, not elements in a tightly structured exchange. At the limit they proxied for handshakes, or hugs, which communicate less by what they say than by their visceral physical fact. Each card traced a wavy, wayfaring line to an equally itinerant other—or better, brother—while signifying, like many of Aleš’s lyrics, to say nothing of the dedications fronting his poetry books, a singular event of speaking in second person: “forever you are the only one,” as Derrida confided to his addressee, “to be able to decrypt” what circulates as an “open but illegible letter” (12–13).

~

A postcard’s aspect ratio suggests a floor plan convivial to the prose poem, a genre Aleš found permissive and powerful. If a card’s dimensions justify the “indigence” of its message, as Derrida maintained, limiting from the outset how much language can literally make it onto the surface, that material restriction, strangely enough, would also free Aleš, to indulge the compression traditionally earmarked for verse (22). Unlike his poetry, however, which Aleš would write in fervent bursts of a couple intensive, ascetic weeks, cordoned off from the sprawl of the everyday, the postcard was part of a regular practice, his nocturnal ritual.

~

Get this. When I was downstairs, in the guest room office, in the basement of “Hotel Debeljak,” my host wrote a midnight postcard, just “past the grace period of the 1st day,” while I spoke on the phone before turning in. I found it the next morning, propped near the Moka Express. Simply to tell me how glad he was I was there.

|

|

~

It would be wildly understated, albeit true, to speak to him now, in an essay on postcards, the way so many postcards end: wishing you were here. But this is not about endings, and it is about how my noblest friend continues to call to us. As if leading a poem up into the light, Aleš once began a short postcard to me: Elation perhaps, ordinary happiness for sure. ![]()