MARGRÉT BLÖNDAL

A Conversation with Margrét Blöndal

Gregory Donovan: This afternoon I’m speaking with Margrét Blöndal. Margrét, you’re here in Richmond to put up an exhibition at the Solvent Space and I was asking you earlier—when you came here to Richmond, you brought along some materials with you and then you gathered others around Richmond. Did you go to the space itself, and did you interact with the space for a while before you decided to do that? And what is the process whereby you create an exhibition in a particular space?

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

Margrét Blöndal: Well, sometimes I refer to it as this continuous sourdough. So, I take part of what I already have and I add that to the new work. And, in this case, I brought actually a little bag with me that was full of leftovers, like balloon snippets, and threads, and, you know, colors, different kinds of colors, and then I stayed maybe two days in the space just figuring it out, and started by using my own material. Then I realized I needed some more. And I also think it’s important when you go to a new place to—well you bring something with you, but then you connect to the place by using some of the things that are available there. So I went to the hardware store, and then I went to some thrift stores and to stores that sell exercise equipment. And I found some things.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

GD: And you were saying that when you begin to assemble those materials you also are interested in the interaction between the materials. In the space at Solvent Space you created five areas of assemblage activity that you did. And they not only speak of themselves, but they also speak dynamically to each other.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

MB:

Yeah, and I think that’s quite important. Every show I do consists of different elements and I think because they refer to each other. And I couldn’t even put this show up again. And then, I could add an element into it. When I’m installing and when I’m deciding how many of them will be together, it’s a little bit like you’re having acupressure massage. There are certain points that just relate to each other and you just know when there is enough. And, because this is a huge space—and the height is eighteen feet—so I thought that I would need more work, actually. But then I ended up editing a lot, and I ended up cutting down material. And I think that’s an interesting thing, because that’s when the work starts to breathe. And you have to be really aware of that.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

GD: One of the things that I considered as I was looking at your work is that, in the case of your work, it’s not as though you’re attempting to dominate the space, but quite the reverse. The space seems to be almost like a mental space into which you enter, and then the work itself is like a conversation among the pieces, and that the pieces there are themselves almost like a kind of language.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

MB: In this particular space. Because, even though it’s painted white, it has a lot of details and it was quite difficult. It took me some time to find out, like, how do you activate the space without being . . . because it’s quite easy to start playing with details. But then it just becomes so obvious that it’s not interesting. I like to enter a space and just use what is in there. I don’t want to alter it. Sometimes I can pull out extra tables or chairs, something like that, but I usually don’t cover anything. Or, if there are spots, you know, on the floor, I don’t really, I might clean the floor. I try to use it as it is, and just try to find a way so it starts to—it becomes alive.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

GD: I noticed that in the blue piece that was in one part of the floor—it had an opening in the center of it.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

MB: Yeah.

GD: That opened onto a particular spot on the floor. Was that something you chose, or was that just a random . . . ?

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

MB: Yeah, that was a random thing. And that’s also interesting . . . like, where I install them, because it’s important to me that the work look incidental. Although they’re all made with my hands, and sometimes there’s a lot of devotion that goes into it—actually handling the material—and it’s very much based on handling it. Still, I would like them to appear as if they could have just fallen down from the ceiling, or they could just have all of a sudden have appeared and then they disappear again. You know, so it’s just like this thing, or this moment.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

GD: You’ve been involved in some art projects that actively involve people moving through large spaces to encounter the work. It was in Reykjavik . . . where you put paintings onto buildings and they were very high up off the ground and perhaps wouldn’t be noticed by people at first, and they might not even realize what they were—or they might act on their subconsciousness, subliminally. As you chose to engage in that artwork, was there a sense that you didn’t want to, again, dominate the landscape?

|

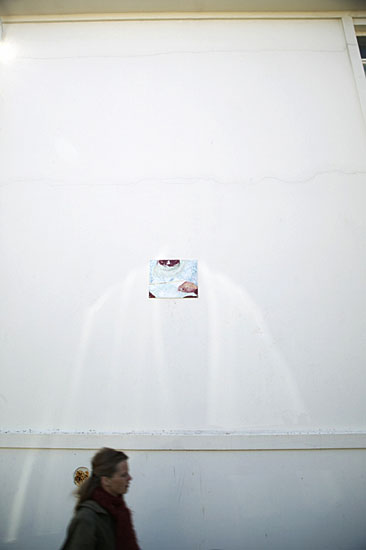

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005, curated by Jessica Morgan.

Thirteen images, silk screen printed and painted on pvc boards,

mounted on houses in a residential area of down-town Reykjavík.

All photos by Fridrik Örn

|

|

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005

|

|

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005

|

MB: Yeah. And especially in this, because I was entering a place of intimacy. I was putting work up on people’s houses, so it was important to respect that . . . because they were private homes that I was using, but at the same time, I wanted to create this window that would just slightly open, just slightly invite visitors. And to suggest this world that exists behind the wall, you know. And, it took me a while to figure out the scale of these images, because first I thought they needed to be bigger. But then I realized that you only needed small ones. So, they were like little stamps on the houses. But they made so much difference, because it was just like you put a little sparkle on the house, when finally you paid attention to them. And you started to pay attention also to all the houses in between, the houses that did not have anything on them. That was something that I was quite happy with. So people would take a walk on that street, which was in walking distance from one of the big museums in downtown Reykjavik, so this whole tour became like a performance. And a friend of mine told me when she took this walk there was this father pushing a stroller and a child was singing and it all became a part of it. And that’s so often with life, or with things that we are experiencing, sometimes we need just to shift focus a little bit to pay attention to it. When even though you are walking your own street, just the fact that all of a sudden there are certain images—and you have to look for them, so it becomes like a play. It puts you into a different way of perceiving things, you know, it’s like being in an active film.

|

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005

|

|

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005

|

|

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005

|

GD: I wondered if the people . . . how they responded to the idea of taking the work down?

|

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005

|

MB: Well, some of them are still there. You know it was a difficult thing for me—there were thirteen images—and I had to go to each house and I had to knock on the door. And most of the houses in Reykjavik, they are made of concrete, so I had to ask for permission, is it OK that I drill nine holes into your wall? And, it was really a frightening idea to me because I was so scared that I would ruin something. But, fortunately, people were quite generous. I asked if they could be up for a certain period of time. In some houses there were several apartments, so you needed to talk to each person on each floor. And I actually took them down much later than I had promised. I was so scared that I was offending them. So finally I just . . . I took them down. But some of them are still up.

|

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005

|

GD: That seems like offering people a chance to live in their own home areas in a different way . . . it seemed like maybe they would be disappointed after they got used to doing that for a while, they would be disappointed to have to go back to the old way of living.

MB: But still, it’s, like, so subtle—because it’s not . . . it doesn’t interfere with anything that goes inside. It’s just on the outside.

|

Material Time, Work Time, Life Time,

Reykjavik Art Festival, 2005

|

GD: You sometimes, in the course of your work, use bits of text that you will occasionally make part of the art work that is on the wall, or, obviously, also sometimes as descriptions of the work. And, when you do that, they are in English. I wondered why you chose the English language?

|

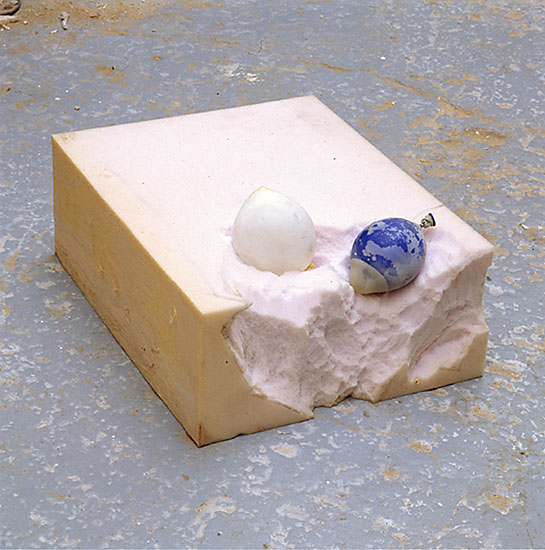

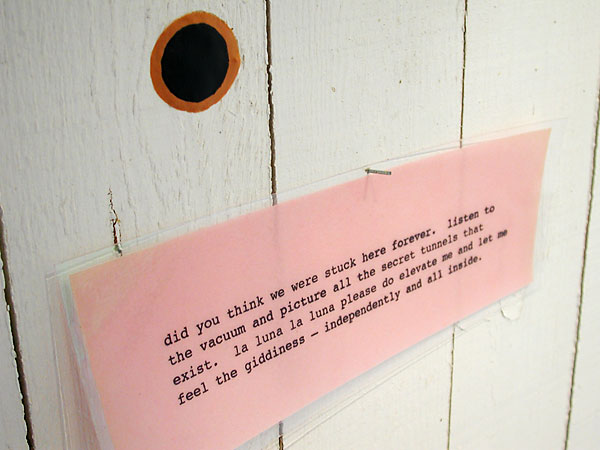

Artist on the Corner

curated by Gabríela Fridriksdóttir and Ásmundur Ásmundsson

here and there in Reykjavík 2002

|

|

Artist on the Corner

curated by Gabríela Fridriksdóttir and Ásmundur Ásmundsson

here and there in Reykjavík, 2002

|

MB: Well, I might do some in Icelandic in Iceland. I enjoy very much writing in English because I can separate myself from this language, and I can use it as if it was a drawing tool. So the texts that I write, I think of them more as a drawing. So, when I include them in the show, they are like one of the elements . . . they are not descriptive of what is going on, not when they’re included in the show. And that’s also when I’m asked to write about my show I cannot write directly of “This piece consists . . . ,” you know, that’s very difficult for me. I try to have the same approach to the description as the works are composed, so it’s this parallel approach.

GD: Well, I think a lot of the descriptions that you create of your work are quite beautiful. And they feel something like poems. Although you were saying they’re not intended to be poems.

MB: It’s about this openness. They are open. I appreciate very much an artist that allows you to breathe. And I think that my work relates to that space in mind . . . that doesn’t have to do with words, and sometimes I say they are like these hummocks that you can just sit on or you can just hold onto to just catch your breath. So you can make your mind a little bit bigger for a while.

|

Buenos días Santiago: une exposition

curated by Jean-Paul Felley & Olivier Kaeser

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Santiago de Chile, 2005

|

GD: In experiencing the exhibition that you’ve put up in the Solvent Space—and in imagining what the experience might be like to witness in person some of the other artworks I’ve only seen in photographs—those experiences that I’ve had, they feel very much like reading good poetry. So, they’re art experiences, of course—there’s a natural parallel. What I mean, specifically, is that they have the quality of entering a state of mind. Because the spaces are open and they have a lot of breathing space in them; the viewer is a participant very much in allowing them to interact and be what they’re going to be. Is that something that you’re pondering or considering as you’re making the art, or . . . ?

MB: I’m not consciously thinking of poetry, but I guess it’s just inside me, you know; it’s part of me. And that’s the process of composing the installation. It’s very similar.

GD: Yes. When you said that you started with many objects you thought that you would need, because the space was so large you would need to fill it . . .

MB: Yes . . .

GD: . . . and then later on, you began to take away the excess. I think that’s very much a part of the process of composing a poem.

MB: Yeah. That also, like editing . . . it also has to do with each piece by itself, or each element I started, like, taking, because I think most of us have the tendency to overdo it in the beginning. Especially if you want the works to look . . . incidental . . . or like they have just been thrown in the corner. It’s a tricky thing to do because, of course, you are in control, but still you have to be aware of all the incidents that happen. So it’s like this reconciliation between control and coincidence.

GD: One of the things that you were mentioning in your artist’s talk, and that we mentioned earlier today when we were just chatting, is that you don’t feel compelled to go into the studio every day.

MB: No, I don’t, because I have different periods of working—sections. And, for me I don’t believe in production. You know, I cannot go to the studio and just start pouring out work. And sometimes I like also to work at home. So, it differs from time to time what I do. And then I get into this intensive time period maybe when I have a lot of shows in a row, so you have to be quite productive there, but that requires a lot of preparation, and the preparation is not necessarily in the studio making the works. It can be exercises like when you are just inhaling what it is to be alive. But I do things to restrict myself. And like sometimes for me it can be very good just to sit at the computer and write letters to people that are quite close to me and I could live forever in the world. But to concentrate your thoughts and to form your thoughts in a certain way . . . that can be quite helpful for me. And, I’ve been doing these drawings with watercolors and olive oil, because when you sit down, and you do something . . . that allows you to really observe things, really go deeply into it. Because when I am doing that, this little factory in your mind that keeps . . . then it starts to be active.

|

Studio view of work for Material Time, Work Time, Life Time, 2000

|

GD: Very often in your pieces, there are elements that allow for time to change them. There is the piece that you made with plaster and balloons and the balloons deflated and changed the piece. Or another piece was with foam and balloons and the balloons have water in them, and the water would eventually evaporate. And in the Solvent Space piece—you were mentioning that one of the elements in the exhibition that was hanging from the ceiling, it turned, and therefore its shadow would change and the way it presented itself to viewers would change. Is that something that you like to make sure is incorporated into your art?

|

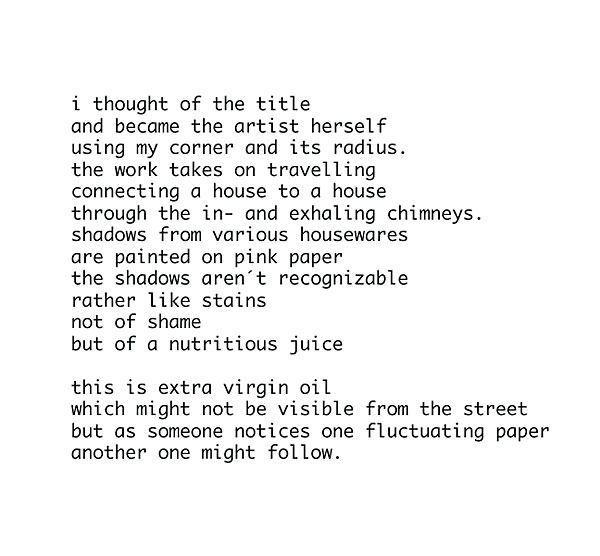

Untitled, 2000

Plaster, balloons, water

|

|

Untitled, 2000

Foam, balloons, water

|

MB: Yeah, because I think I am commenting on what it is to be alive. And, I’m not interested in building monuments that will stay forever as monuments. I'm more interested in this thing that just passes. They are just passing through in these transient moments. And it’s not that I am forcing myself to find material that will change. It’s not like that. I use a lot of rubber that gets...

GD: Decays? It rots?

MB: Yeah, yeah. Yes. So it will change, or it requires being taken care of.

GD: There was a piece that you did that involved foam with balls piled on top and you were saying it was possible for passing trucks to vibrate this piece and cause the balls, which you had very carefully stacked in this way, to come tumbling down—and then someone else had to rearrange them. Was that something you hoped?

|

Untitled, 2000

Foam, balls

|

MB: I did not hope for it, because I felt a little bit bad for the people that are taking care of it . . . but it just happened. And I think that’s just part of life. There are certain things that you cannot control. And I did not want to force them together by using glue, which would not be part of the work.

GD: You had another piece made of sugar, and you said that it also transformed itself over time.

MB: That was just made out of pure sugar that was melted and pour into plaster mold. And it was quite sensitive to the humidity, so it became sticky and even during the summertime if it was exposed to air it started to melt really fast.

|

Untitled, 2000

Sugar

|

GD: Is that how it acquired the color that it has—it was from the heating process?

MB: Yeah, because I poured it in many different layers. So, it had the stratifications. But that was something that I could not control. It’s not only that they change in time. But they are often quite fragile, and it doesn’t need much for them to tip over. And I think a lot of them . . . they’re trying to hold balance.

GD: That’s something that I noticed in the exhibition at Solvent Space, and in many others of your work. There seems to be an element dealing with gravity, that things are hanging, or they’re suspended, or they’re leaning against things.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

MB: Yeah.

GD: Is that a demand on your work that is created by the spaces themselves, or is that something that interests you, in terms of how it feels to create work that is working with gravity?

MB: Well, maybe what interests me is this thing of . . . like, every person needs to look for comfort or to look for shelter in some way, and how vulnerable we are. So I think that’s the core. But I’m not consciously thinking of it. Like when I was saying about these acupressure points. Or it’s like music. You need one hanging element, and then I feel one element that would be here . . . slowly going from one element to each other. Just one element might need to be heavier than the other, and include gravity, just this connection to the ground.

GD: I think that’s something that I’ve seen a lot in your work . . . that there are elements that are dynamically interacting.

MB: Now, they’re more like drawings into the space. They are lighter. Before, they were heavier, and I thought of them as reminders. I wanted the viewer to get confronted with the work, not that he would just come to a space and look at things on display. He would be confronted in two ways: both physically, because they might be in his way—and then psychologically as well. I mean, it could be a confrontation on many different levels.

GD: In the work that you did at the Alma Löv Museum in Sweden—that involved going into spaces that there were all these . . . what one might call “little houses”—independent rooms, set all about in a forested space. It seems there’s a drama going on in the presentation, and that you enter into it, and then it unfolds as you experience it. It had a central element with these balls floating in water. There was a reproduced photograph on the wall, and then there were also elements of text that you used. How do you feel about the interrelationship between text and visual elements in a visual art presentation?

|

Alma Löv Museum, Sweden 2002

|

|

Alma Löv Museum, Sweden 2002

|

|

Alma Löv Museum, Sweden 2002

|

|

Alma Löv Museum, Sweden 2002

|

MB: When I was asked to do a show in this space . . . well, it was quite a poetic space, and I thought that I just couldn’t bring in objects and put them up. It would kill the space. And I had to hand in something for the catalog. So I wrote a text that was just based on the image I got of this space. It included a tree that was growing out of the second step of the stairs that led to the pavilion. When I came, and I actually spent some time in the space, I realized that, you know, if I had included the whole text, it would just be like a story, and it’s not interesting, because it’s too descriptive when you’re looking at something and you’re experiencing it visually. There were different elements. There was this one thing that you could walk around, this center space that was open to the air. So there was this air always coming in. And the water was from rain. There was this element of something floating.

GD: Nevertheless, I would say that—perhaps it’s simply because of the way that you’ve selected text—but it’s really very interesting text, and stimulating. You read a little bit of it in the artist talk that you did. And would you mind reading just a little bit of it?

MB: [reads] “i hope that the babybirds will be able to sculpt their way through their solitude because socializing can be good. oh suck can you suck while the balls are bouncing. oh suck can you suck while the seeds are fertilizing.

the sirens sang and filled the nose at the same time. do you like aroma in your palate... i dislike very much the thick layer that coagulates in the gum after eating a special kind of a sausage. there are sausages from skåne that resemble fat fingers but have a totally different attitude and affect than the lady fingers they eat in the states.

ville, valle and victor wanted to row row row. they found a molded bucket and old underclothes that they used for a sail - yes the tree v´s sure knew how to turn the situation to their favour. i assure you that i try i do i really try.”

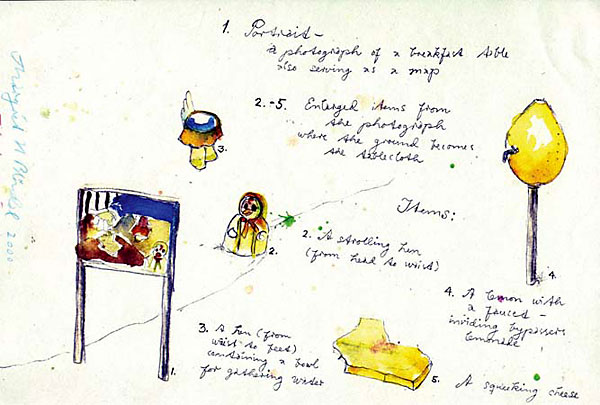

GD: In other occasions you have created work that you begin with a photograph and then allow that to be a kind of goading element. The piece in Helsinki was a photograph taken of what probably is a breakfast, with some rather mysterious elements there, but one that I guess that’s an egg holder?

MB: It was an Easter morning, actually.

|

Tölöölahti, Art Gardens, Helsinki 2000

|

|

Tölöölahti, Art Gardens, Helsinki 2000

|

|

Tölöölahti, Art Gardens, Helsinki 2000

|

|

Tölöölahti, Art Gardens, Helsinki 2000

|

GD: And then these objects, when you recreated them, they become much larger. And occupy a field in an open space. I wondered if you would talk a little bit about how you challenge yourself with what material you start with and then how you allow that to push you into making the ultimate, realized artwork.

MB: Well, I always look for hints with every exhibition invitation, or every project that I participate in. I have to look for some hints to start with. You have to find one fixed point that allows all the stars to move all around you. In this case, it was inspired by Helsinki [which] was a cultural city of Europe [in 2000, Helsinki was named a Capital of Culture by the European Union], there were a lot of things going on. They took this part that was downtown Helsinki, very close to the contemporary art museum. It used to be a wasteland. But still, people would go there to take a walk. It was quite a popular place and all of a sudden they changed it. They had this designer design this beautiful garden. And then they had these different artists coming to have a show. I had this image of the breakfast table and I just thought, “Well, this is what we are doing.” I decided that the tablecloth would be the ground. And then, since there were going to be not a regular crowd of people that come to the galleries, but it would be all kinds of people, and I wanted it to be playful. So I decided to enlarge the elements. And like the lime, you could get fresh lemonade from it, and the cheese—you could jump on it—would give this squeezing sound. The part of the hand, you could crawl into it and play with it. It was no more complicated than that.

GD: In the piece at the Solvent Space, I noticed that some areas of elements of the exhibition, you used a rather limited palette—as if they had a particular color scheme, and yet they did relate to each other. There’s one part that’s hanging on the wall that has red rubber elements. I don’t know why it was, but those red rubber elements seem kind of threatening to me or sort of aggressive. And that was very different from the effect of the piece that was hanging from the ceiling. It was quite complex, but it had less of a quality of feeling threatening. Is that a psychological experience I was having? Is that something you’re hoping to open for your viewers?

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

MB: It’s always a subtle thing when you put things together. Also, like, with the texture right . . . because if it becomes too sweet you need to have a certain twist in there. It needs to have some kind of edge that will grab you. I did not deliberately select these red tubes because for me, they are not threatening. Maybe it just needs some color. This particular part needs something that calls for attention. So that might be the drive. To me it’s just always more interesting if there is some twist. There is an edge to the work. With my work they require time. You don’t get them immediately. As you spend time with them, they grow.

|

Untitled, Solvent Space, Richmond, Virginia, 2007

|

GD: So they’re the physical manifestation of that process. You’ve done some teaching as well in the past . . .

MB: I enjoy teaching very much, and I have a great respect for that, especially when your job is to stimulate. And I enjoy to create assignments that challenge every person. I think it’s a similar approach to the work. You come up with an assignment that every single person can participate in— and not just pretending, but can sincerely participate in—and they will be equals in a sense . . . that all are participating. I mean, they are not just participating to participate, but they are being challenged, in a way. They’re actively participating in it. Usually I do it by very simple assignments. Maybe by playing with color. But it’s interesting to create an assignment that . . . because I have taught such a variety of people, all from day care center up to university level, and also this age span, from three years old to eighty-something years old. The core of teaching is always the same. It’s the same thing that you’re doing; you just have to read the atmosphere and you have to be aware of what’s going on in the room. And then you start pulling the strings. And it’s a little bit like putting up this installation. Here you need to pull this thread a little bit longer, and you need to emphasize this. So it is quite similar.

GD: When you graduated with your MFA degree from Rutgers, you no doubt had some passions and notions about how you were going to go about making art. And, do you feel that that’s changing over time? Or has it changed?

MB: Well, not about how I’m going about it. I don’t think so much about the future. I have my moments of anxiety and all of that, but maybe I’ve been fortunate. There are always some opportunities that have come to me, some projects that enable me to continue on this path. When I graduated from Rutgers I needed some kind of framework. It was good for me to go to classes and to have a part-time teaching job, because that became a frame to me. But now I don’t need that as a stimulation, you know, because, well, I have come up with a different working method. It is like this continuous process.

GD: Do you find that this experience of coming to a city, where you don’t know people and that you’re plunged into the middle of this experience—is that a stimulating challenge as well? You only had a limited amount of time to do this artwork.

MB: Well, I could have brought finished work with me that would not have been “finished.” I would still have to find a place for them in the room. This can be challenging. I like very much when I have the opportunity to spend at least a week (as I did now) so I can come up with new work in a new space, especially in this context, because this is a university setting. This is a space that allows you to be playful inside. But some other shows that don’t allow you that time because you only have two days to install . . . so I have to bring the work with me. I think, coming from this island, it sets an important thing, to go away. And it’s not only for myself, it’s also for the work, so they will have breathing space. Because if they are just surrounded by always the same contour, they just would suffocate. With all respect to my country, the natives . . . it doesn’t have to do with . . . just to be able to go to different places.

GD: Thank you very much.

Contributor’s

notes

Interviews

return to top

|