Commentary on Brainstrips by Neal Wyatt

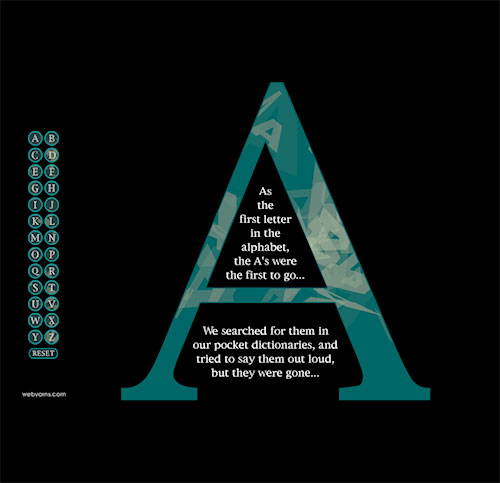

I first encountered Alan Bigelow upon reading Saving The Alphabet, a story about the loss of language. Against a black computer screen, the story, created in the computer program Flash, unfolds in twenty-six “pages,” one for each letter of the alphabet and accessible in any order by a menu that looks like letters on an old-fashioned typewriter. Before the story even begins, Bigelow provides a soundtrack, a ghostly, watery music, which sets the tone for the story to come.

|

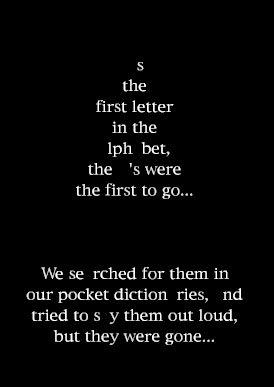

As I first read the story of a dystopian world where a massive corporation is confiscating letters, the letters in the story itself began to disappear. Proceeding in alphabetical order, soon “A,” “B,” and “C” began to fade. As I read the story about the citizens of this dystopian world searching for the lost letters, on my screen such critical vowels as “E” and “I” faded away.

|

Bigelow’s work visually enacts this story on the reader, stealing the letters one by one. The letters left the story right before my eyes, fading away into the dark background of the screen, turning at first into grey echoes, and then, finally, disappearing completely. All that is left at the end are a few stray symbols and the endlessly echoing music.

In the world of digital writing, where the process of reading is manipulated and augmented by the multimedia tools used to write the story, new kinds of literary works are possible. Just as movies have reached a point where the real and the possible have been replaced with computer generated graphics, writing is expanding into different forms.

There is a rich possibility in that unsteady space for surprise.

Most notably, I was surprised to discover that I was not just a reader, but a viewer and a listener too. Bigelow’s pieces integrate animation and sound into the written works, providing an opportunity to consider how audio and images support and influence the reading process.

Bigelow does not always write such strongly text-based works as Saving the Alphabet. Often he presents pieces that rely more heavily on sound and animation.

Within Brainstrips, the multipart work appearing in this issue of Blackbird, the audio track (wedding bells) of “Are Men More Sensitive Than Women?” underscores the sly irony of this piece, an irony common to many of Bigelow’s works.

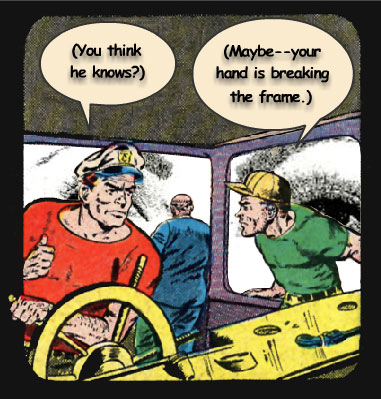

In “Is Color Real?” one of the most compelling uses of animation is the looping depiction of “the outside reader” visible through the windows of the boat, unseen only by the character in blue, who a frame before says “I sense a blackness all around us.” This is not just an example of what the novelist Tom De Haven calls “good comics,” this conducts a narrative slight of hand that invites me to imagine myself as a reader both inside and outside of the frame.

|

While a work such as Saving The Alphabet is clearly narrative, the collective works in Brainstrips are not so easily classified. Some of the pieces in Brainstrips like “The Special Theory of Relativity” are more akin to haiku—leaving me with moments of revelation. Other pieces, such as “The Googolplex” and “Gravity And You” feel like labyrinths, mazes of words, images, and sounds set before us to navigate. “Global Warming” and “Nuclear Fission” create a clever commentary, the equivalent of multimedia New Yorker cartoons.

The process of exploration, figuring out both what the work is and how to read it, is part of the pleasure Bigelow gives me as a reader. I have ingrained expectations when I read, but digital writing upends those expectations and invites me to explore what else reading can be. As I use a mouse to navigate space rather than turn pages, as I decode image and sound along with text to enact the story these writers want to share, I participate in a new method of reading.

After you explore Brainstrips in this issue of Blackird, I invite you to read more work available on the web by Alan Bigelow (in particular, My Summer Vacation, My Novel.org, and Saving The Alphabet) as well as some of the works of his fellow digital writers, including the fascinating work by Andy Campbell of Dreaming Methods and Jim Andrews at Vispo.com.

If the road gets a bit rocky during your explorations, if you feel like you are lost in the maze, just remember: despite all the distress about the death of reading and the end of the book as we know it, writers as canonical as Cervantes, Sterne, Woolf, and Joyce have invited readers before to step onto shaky ground and read in the unsteady space of the new. ![]()

Neal Wyatt is a second-year student in the Virginia Commonwealth University Media, Art, and Text PhD program and is the Blackbird Associate Audio Editor for 2009–2010.

Introduction | Reader Commentary | A Note on Process | Launch Brainstrips