print version

print versionA Conversation with Kristen Radtke

Mary Selph: What first drew you to the video essay as a form? Why is it a form that continues to attract you?

|

|

Kristen Radtke: By the time I hit my second year of graduate school, I was really sick of myself as a writer. I wish there were a more profound way to put that, but I was working over the same ideas that kept pulling me back—aftermath, ruins, decay—and I wasn’t satisfied with how they were landing on the page. I started drawing, then I started working those drawings into my essays, but I couldn’t get them to fit together as I wanted.

In the middle of one disastrous illustrated essay, I saw the wonderful John Bresland screen a video at the 2010 Nonfiction Now Conference, held at the University of Iowa. I loved the way he used off-the-page elements—sound, color, abstract shapes—so simply to create something whole and elegant. I remember wandering out of the conference hall sort of bleary-eyed and into the university’s English building across the street where I stayed locked in the audio lab for the next thirty or so hours, recording and drawing and trying to figure out how I could make those drawings move.

| There were so few video essays out there. I wanted there to be more. I still want there to be more. |

||

I had no idea what I was doing. I took a few naps on the floor and had pizza delivered and asked my neighbor to check on my cat. It was maybe the first project I felt driven to finish as fast as I could. There were so few video essays out there. I wanted there to be more. I still want there to be more.

MS: It’s interesting that you came to video essays through John Bresland’s work. Did you have film or video experience before your first video essay project?

KR: None. At first, most of the problems I dealt with were technical rather than creative. Maybe this worked to my advantage. Put up some blockades, slow yourself down; maybe interesting things can happen.

MS: Is there other video work that has been particularly influential or important to you?

KR: Chris Marker has been hugely influential. Jeremy Blake was a wonderful video artist. Su Friedrich has done a lot of interesting work, and I love Ralph Arlyck’s narratives.

|

|

MS: Has working with video essays changed how you approach non-video work?

KR: This is a really good question. I have absolutely no idea, other than to note that I’ve since moved back to making a lot of illustrated essays, which was the very thing I was trying to avoid when I began video work.

MS: How do your video essays come about? Is their impetus rooted in a particular form?

KR: Thus far, my process has been pretty unchanging: write the text, draw the static images, record the narration, pull the images apart and animate them, and then see how it works together. Usually that means going back and revising the text and images a fair amount along the way. I’d love to challenge myself to uproot that formula, see what happens if I draw the images first, or create an animation that unfolds in a different way. I did a stop-motion video on a projector once with cutout images, and I’d like to do something tactile like that again, except with an animation that moves in a more traditionally narrative way.

MS: What is the role that non-verbal sounds play in your video work?

KR: Right around the time I started making videos, my friend Jose Orduña (a wonderful writer everyone should go read immediately) and I were collaborating on audio projects, and I’d listen to what he’d make, how he’d manipulate and overlay, how sounds intrude upon and complicate and make the text come alive. I know that’s probably not a skill I have.

For me, the best I hope to do is make sound that contributes to a mood without calling too much attention to itself. Usually that means lying in bed all day and recording the sound of my feet on sheets, cups being dragged across the nightstand, the lamp flicking on and off, an airplane flying overhead, and jumbling them up until they make something that fits behind the narration.

MS: Could you talk some about your other work (video essay and otherwise) and how “Ruin” fits in? Do you see “Ruin” as part of a larger series? How do you see some of the different threads in “Ruin” (historical, contemporary, personal) working together?

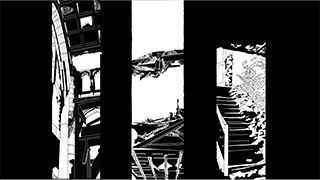

KR: I’m currently finishing up a graphic memoir about an obsession with aftermath and abandoned places, and an illustrated essay version of “Ruin” fits into that. I see it as a kind of historical catalog of how humans have regarded non-wartime ruins in the Western world. It culminates with Detroit, our most visceral and present example.

|

|

Culturally, we’ve long fetishized ruin and decay, and that’s perhaps where the personal comes in—we’re all implicated in that. With Detroit, we’ve seen some outrage in reaction to that fetishization. I’ve tried to gesture at fear as a likely cause for that anger, but there’s certainly nothing definitive about that interpretation.

MS: How did you come to focus on Detroit in this piece?

KR: There’s been a pretty vocal backlash against some of the journalism that came out of post-automobile wealth and pre-bankruptcy Detroit. It became a cool thing for artists to go set up shop there, for twenty-somethings to wander around and take pictures and post them to their blogs, and there are a lot of ways we could call that exploitive. If I were a longtime resident of Detroit, I think it’d probably make me pretty angry.

But I think there’s a way we can pay attention without exploiting, and I think what we call exploitation is often just a way of looking that makes us uncomfortable. Detroit was full of promise and power and money. To see a major American city falter reminds us that every other place can, too.

| Detroit isn’t full of ruins the way we traditionally think of ruins. It’s not evidence of a previous civilization. It’s proof that we’re all vulnerable, right now. |

||

These are pretty generic observations, and acknowledging them doesn’t mean we’re going to change our behavior. Tokyo is the most populous city in the world, and it’s also on one of the most volatile plots of land on earth. We’ve been building unsustainable lives and leaving them forever. Detroit is just the largest example of that in recent history, and that’s why it’s so terrifying.

Detroit isn’t full of ruins the way we traditionally think of ruins. It’s not evidence of a previous civilization. It’s proof that we’re all vulnerable, right now.

MS: Your work is striking for its combination of intricate visuals and tight language. How do you understand the relationship between images and verbal language?

KR: That’s definitely the goal of work that combines text and image—creating both without being redundant, complicating without throwing a reader/viewer off course (unless that diversion is part of the intention). I don’t know that I’ve completely figured it out yet, but it’s always something I spend a lot of time worrying about.

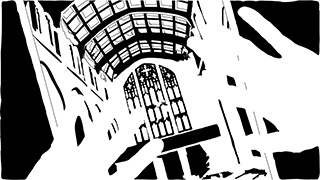

MS: There seems to be a tension between the verbal discussion of ruins in this piece and the way the images appear—gradually, as if in the process of being drawn or created, before vanishing from the screen—with each new image built in the wake of the previous one(s). How did the visual elements of “Ruin” come to move the way they do?

KR: I’m really curious about the way that things come apart, and juxtaposing that curiosity with how images are drawn felt like an interesting experiment. I like the idea of making lines that become shapes that become spaces and objects, because maybe it works the way we try to work as artists. You’re brushing your teeth one morning and you get an idea, and that keeps you going until you discover all of these problems that complicate that idea, and then you build on those complications until you’ve made the beginnings of something. Maybe everything will be different the next morning.

|

|

I think we all have to be ready to throw things away and start again. That goes for the way we write essays and stories and books, and maybe even the way we leave buildings and towns to rot. I hope it applies to the way images assemble before disappearing here.

MS: The ending sequence of “Ruin” is haunting because the viewer becomes implicated along with the speaker. At the same time, the very personal and tactile image of hands overlaying ruins appears. How did you come to this place as an ending both in terms of the voice and of the visual imagery?

KR: I’m totally part of the problem. I became obsessed with crumbling places and I spent hundreds of hours researching them, saved up all of my money to buy plane tickets so I could crawl through them. I go, I see, I leave. I write about it. I think we have a tendency to think the things we write matter, and maybe sometimes they do. But the notion that learning about a city’s problems or writing about a place that’s not yours adds up to something is a dangerous one.

I’m trying to say something about our fascination with Detroit, just like I’ve tried to say something about our smaller fascination with Gary, Indiana, or mining towns throughout the West rumored to be haunted. I’m not trying to say anything about Detroit or Gary or the mining towns that may or may not be haunted. Go ahead and Google “ruin porn” or “urban exploration” or “abandoned cities” and you’ll find panoramic photographs of molding, collapsing buildings, and below them hundreds of comments about how beautiful it all is.

And that’s true. Very often, these places are very beautiful. But what is it that we really find appealing? Because it feels wrong or unimaginable? Because we want evidence of time as long as it’s not on our own bodies? Ogling photographs of decaying places lets us dip into that contradiction without having to commit to any of it. If the photographs were of our own homes, our reactions would be quite different.

We want—and don’t want—to know what things will look like when we’re gone. ![]()

Ruin ![]()

A Conversation with Kristen Radtke