print preview

print previewback CHARLES WRIGHT

Improvisations on David Freed

|

|

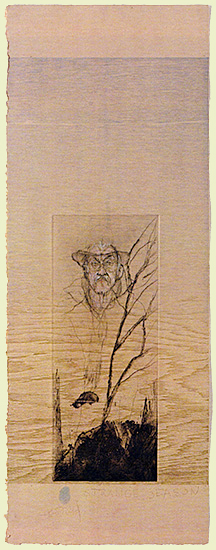

| Strange Season IV, 2011 Etching, relief, pastel 30 x 10 in. |

I’ve been looking at David Freed’s work for almost forty years now, ever since a mutual friend of ours, herself an artist, said he was the best printmaker in school. This was in 1962, at the University of Iowa. Better than Lasansky, she added. That would be Mauricio Lasansky, Dave’s teacher and world famous printmaker. Whatever the merits of our friend’s convictions, she was on to something. After all these years, he’s still the best printmaker in the school, although the school has gotten appreciably larger and wider.

There is a modesty in Freed’s work—not of ambition, but of presentation—that is like the spread of light in certain Renaissance paintings. It not only backdrops everything, but tends to suffuse everything as well. One doesn’t know where it comes from, but it is everywhere, enlightening, leaving us, somehow, more room to look in, a seduction of sorts that eschews excess.

His figures have always struck me as figures in a landscape, even if they are portraits, or interiors. Which is to say, something always surrounds them, informing them in their isolation as part of something larger, something we understand and feel, though don’t always comprehend. Whether we see it or not, it’s there. An attitude, perhaps—not one imposed but one revealed, the only attitude that counts.

Dave published and illustrated the second little book I ever did, back in 1963–1964, when we were both Fulbright students, he in England, I in Italy. The poems were largely forgettable, but not so the engravings. Six engravings, six poems. To this day I have one of the prints, a portrait of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud, on my wall. Now that’s staying power.

Another piece of Dave’s work I have on my wall, the wall of my school office, is a drawing of me he did fairly recently, a figure, as it happens, in a landscape of sorts, turned and looking out toward the viewer. Hands in pockets. It’s called East of the Blue Ridge. The figure’s face has no features, a face that is smoked and shaded in, peering out at the peerer in. Not one person who has remarked on the drawing—and there have been many over the four or five years it’s been on the wall—has failed to say, That looks just like you. Not one. Now that’s the attitude I alluded to. That’s what I’m talking about.

Sam Goldwyn or Jack Warner, or one of those early Hollywood moguls, is reported to have said, regarding the criticism of one of his pictures, If they want a message, tell them to send a telegram. Or words to the effect. Well, David’s telegram has arrived, and it says the world is real, figures are real, the line is real, and they are all things of this world. Of course, who helped him compose this message in the midst of making all his pictures, and where he keeps on sending it from, and how, is another matter indeed.

And one more thing. There is a kind of mordant wit that informs all of Dave’s work, a scintillation that often goes, and shouldn’t, unnoticed. He is, by now, his own school, an artist who sees with all three eyes, the guy who walks by himself along the banks of the black river. But unlike Orpheus, he doesn’t look back. In fact, as the poet William Carlos Williams said of Pieter Brueghel the Elder, “. . . Brueghel saw it all / and with his grim / humor faithfully / recorded / it.” Dave does too. ![]()

![]()

This essay originally appeared in David Freed: Printmaker, a Retrospective (Anderson Gallery, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001).