print preview

print previewback LEIA DARWISH

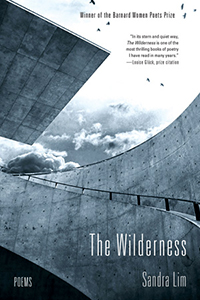

Review | The Wilderness, by Sandra Lim

W. W. Norton & Company, 2014

|

The usual qualities we consider with poetry—image, metaphor, voice—do not matter so much in The Wilderness as much as the strange and unanswerable dialect of the confessional philosopher-poet. This unforgettably different collection, Sandra Lim’s second, moves to expose the intimate moment of first scripture: the lines inscribed on the cave walls of the mind. Though love and death stand in as tentative subjects, The Wilderness obsesses over an ineffable space between things. Lim’s book challenges everything we think we know about a poetry not fully realized on the page—not fragmentation, but deconstruction.

This collection, with all its strengths and weaknesses, represents a braver accomplishment than war poetry, poetry of grief, or experimental poetry. With her psychological concern, Lim cuts to the sources of universal human experience. These poems deliver all the seduction of innuendo without the candy coating: “Let the world eat me,” Lim muses in the opening poem, “but / then, let the world sob, not me.” Declaration here takes on the function of imagery—the imagery of thought. In the same way that John Berryman’s nervous syntax offers us insight into his psychological condition, Lim’s specific wilderness reveals itself through her obsessive and disconnected syntax, for example:

The world could be like a faraway planet to which I declare,

Free at last: I shall see my hunger for meaning go.

These schizophrenic insertions, these nearly incessant, manic demands for assuredness, interrupt the flow of her experience in day-to-day life. What first presents itself as a brand of collectedness, emerges, over time, as its exact opposite: desperation.

Faithlessness is a heart glancing down

a plumed avenue

in which one is serenaded by myriad, scattering birds.

Lim compulsively charts and reveals the abstract wilderness. The speaker, for example, in “Certainty,” confesses, “The wilderness: I cannot get around the back of it.” Ultimately, declarations begin to reveal themselves as landmarks—imagine a barren plain littered with tuning forks, each sending out a signal to the others, and resonating, making a tone not easily understood by the conscious mind but one that seems to penetrate with our subconscious. Over the course of the book, as these tuning forks build up, we are imbued with this feeling of recognition so exact it feels it cannot have come from such abstract language: “A blankness without meanness,” she writes in “Fall.” Equally interesting, is how this bypassing of the ego, or conscious mind, keeps the reader at a certain distance. The reader then encounters this complete wilderness of self-efficient ideas, ideas that appear to communicate across a network that doesn’t necessitate the outsider, as an outsider. Resonance requires distance, and alienating the ego is a productive, necessary step in achieving resonance with the subconscious.

You stepped away from this world

so that you could consider it from afar.

While I might feel lost inside the sometimes cryptic, sometimes time-shifting “Ver Novum,” I don’t for a second question it. Lim cannot hide her communion with Berryman, in her language, in the long homage to an homage, “Homage to Mistress Bradstreet,” but the most functional echo I can hear is in the unflinching voice of her speaker. Lim delivers such difficult, deconstructed language with the same dogmatic refusal to meditate or mediate, to guide the reader, that is both the hyper- and anti-awareness of self that we find in The Dream Songs. A final paradox: these poems seem to be an exercise of restraint on one level and indulgence on the other—poems with all the cross-outs left in but all the punchlines left out. In the sparse “Unfleur,” Lim delivers heady statements about grand abstractions but offers a reflection that is helpful only in the way the footnotes to The Waste Land are helpful—that is, one that only further complicates.

What is death

but reason

in flawless submission

to itselfNo

not reasonsomething stonier

Much talk of white space in poetry focuses on silence and subtext—as if holding a blacklight up to the space between stanzas would reveal the omitted details. However, Lim’s white space is less a withholding than a distancing. The white space, the blankness, adds air to the already stark lineation of poems like “Ver Novum” and “Homage to Mistress Bradstreet,” but it may be most effective in the more narrative or philosophical poems, like the two “Certainty” poems or “The New World.” Either the text is prose or the lines sprawl so far to the edge of the page they have the effect of prose, of continuous thought chopped up into several little paragraphs. The nature of the text determines the nature of the blank space—these poems feel like blocks of prose that have been stretched out to magnify the inherent distance between thoughts. There are times when the statements themselves explicitly suffer from a kind of awkward deconstruction:

It was a great relief that my thoughts

had taken over feeling about our sorrows.I wanted to turn over all my wildness to them,

so that they could harbor it in English-language sounds.

I don’t know where to look in sentences like these, but what defines this collection is that the lines I would like to cut are also the lines that draw me closer. These utterly charming, utterly inevitable cowlicks are essential, like a soul, sometimes revealed, sometimes exposed. The poem strobes like a swaying skirt—in the movement, sometimes you catch a little glimpse. These cowlicks of disquiet are endemic to the collection. To engage with The Wilderness as a reader is to find this pain—the convoluted syntax, the traffic jam of sibilants, multisyllabic adjectives and adverbs—charming, ultimately and undeniably refreshing. From “The New World”:

Thunderous wakefulness is ceaseless needles through the casing.

or, in “The Concert”:

Next to a soul,

the body’s curious reticence obtains.

These lines read a little like translation. What could be said precisely with a specific term is said with a phrase, as if no term in English exists to express what Lim intends. There is magic to her imprecision: the more words, the more nodes of relation. This is not the satisfaction of the unequivocal. Each word carries an etymology, a personal history. And so to say something with four words instead of one is to explode, unpack, and deconstruct all the various emotional and historical relations inherent to a single life experience.

“Cheval Sombre,” the lithe, palindrome-shaped poem almost at the center of the collection, suggests that form, while it may be artifice, satisfies a need, as “a soul needs a presence / of desire.” If applied using an architecture of expectation—in this case the eighth line acts as a mirror after which lines 1–7 repeat in reverse order—the gibberish gains an air of inevitability. In this, the most lyrical poem of the collection, a delightful plain truth: the purpose of form, of poetry, is to give our gibberish some inevitability.

“Some kind of belief runs off me in strings,” Lim writes in “The Vanishing World.” Clarifying that belief would be the very work of writing poetry for most other poets, but here we get the thought unmetaphored, as it were, unmoored. This is the euphoria of “fragility and disquiet” Édouard Glissant describes in Poetic Intention as “the suspension between a pessimism knotted to the present and that series of sparks and vibrations the future already holds.” In the throes of disquiet, the artifice of the mellifluous is sometimes sacrificed for a chance to access the elemental psychological wilderness from which such poetry is formed. ![]()

Sandra Lim is the author of The Wilderness (W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), which was selected for the 2013 Barnard Women Poets Prize, and Loveliest Grotesque (Kore Press, 2006). Her poetry and essays have appeared in Boston Review, Guernica, MiPOesias, and The Pushcart Prize XXXIX, among others. A recipient of fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, the Getty Research Institute, and the Jentel Foundation, she is an assistant professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell.