print preview

print previewback SUSAN SETTLEMYRE WILLIAMS

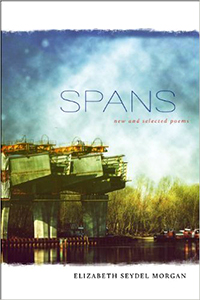

Review | Spans: New and Selected Poems, by Elizabeth Seydel Morgan

Louisiana State University Press, 2014

|

New and Selected both recognizes and represents achievement—a long and distinguished history of literary work. Congratulations to Elizabeth Seydel Morgan, whose aptly titled Spans covers nearly thirty years of publication and four previous collections of fierce, witty, sometimes heartbreaking poetry, much of it focused on one woman’s full if not always pleasurable life.

The persona who lives that life, perhaps not coincidentally, shares many biographical details with the poet herself, from girlhood in Georgia to a mountain cabin in Virginia, from family and friends to private losses,and personal memories associated with big and public events from Vietnam to the civil war in former Yugoslavia to the tenth anniversary of 9/11.

Morgan comes at those events obliquely, setting them against the dailiness of an ordinary life. For example, in the villanelle “September 2011,” the poet suggests, but never addresses, the events of ten years earlier with the alternating refrains, “It keeps on happening again and it will,” and “We’re in the tall building paying the bill” (“overdue” in the daily world “to the city for gas”). In “What Is the Most Elvis Ever Weighed?,” Morgan in fact is remembering the boy “so thin / and young he knew no need or need to hide / from sex-sent sixteen-year-old girls,” one of whom perches herself on his lap. When she asks, “What’s next!” the future King’s innocent reply is “Oh, I don’t know, . . . Let’s go see y’all’s folks.” At a recent reading, Morgan brought along a photograph that illustrates the episode.

I have long followed Morgan’s work and thought I knew it well, but Spans surprised me, not so much with unfamiliar poems but with the clarity that comes into focus only through a long lens. Before this collection, I could have identified many of the characteristics of Morgan’s poetry: the distinctively tart voice (as in “Poetry Reading,” which begins, “This is my last poem: / pay attention.”);an emotional range from tenderness (especially toward the young and her speaker’s own youth) to the anger that accompanies grief to the bitterness of the grieving toward an outside world that goes on (“so normal and present, so light and healthy, / so oblivious to anyone’s ending”); and finally a fine sense of the absurd, as when the speaker, lacking a dog, tries to assume its role and frighten a rabbit out of her garden by barking at it. (The poem ends, “Dumb bunny’s still there, and me, barking.”)

What strikes me most powerfully about Morgan’s oeuvre this time through, however, is the intense push and pull between the need to be among people (friends, neighbors, lovers, children) and the need for retreat and solitude, a tension captured in the titles of two of Morgan’s previous collections, Parties and On Long Mountain, both represented in Spans. Neither state, however, provides enduring comfort. When the speaker is with others, she often feels set apart by private sorrow. Alone, her imagination can drive her nearly to panic.

An early poem complains, “All My Friends’ Pets Are Growing Old,” but, after enumerating their various forms of decrepitude (“a house that reeks of cat / piss, two huge wheezing dogs—one with heart- / worm”), the speaker, against her will, goes back to a time when

we couples stood around somebody’s small backyard,

grilling sirloins, sipping beer, a nudge or hug

to go with watching Millie’s puppy waddle

grass-high toward the plump legs of our diapered babies.

In “Loss Without Ceremony,” a later and more painful poem, the speaker reflects that “this is the most jagged grief, / emptiness unmourned by any rite,” even if the rite is only “peeling potatoes / and chopping onions” with the family of a woman who has just been buried. Someone offers a callow platitude: “It isn’t any consolation.” But Morgan objects that the observer isn’t old enough to have

. . . lived through loss without a ceremony.

Who hadn’t been a man who lost a man he loved in secret.

Or one who from the window watched a moving van back out.

Or one who loves a child whose eyes have turned to walls.

On Long Mountain, by contrast, celebrates the solitary beauties of the Blue Ridge, attempting to capture the surprising glory of a butterfly bush suddenly alive with migrating monarchs like “windwaved flames / or shards of thin stained glass / firing the sunlight to orange and gold.” But a description or even a picture won’t suffice, “it is the movement that amazes. / And no video could do it, missing the scent, / the silence, the feel of the Long Mountain air.” On the other hand, in “Unarmed,” having rejected the advice to “Get a gun” for security in her isolated cabin because her “closest friend” has remarked, “You’d shoot yourself. Out of stupidity. / Or sadness,” the speaker, “lying awake alone / . . . fight[s] fear unarmed.” She imagines a bear “scratched her nails on the windowpane,” and a “hiker crazed for the food / of my flesh, swings my rust-hinged gate,” “while the snake, the copperhead, / slides along the rafter.”

Loss and need may propel Morgan’s speaker from one world to the other, but so does a certain edgy zest for what she finds in each. She can joke about the oddities of her places and her life. Aging, for instance, suggests a deliberate plot against her: Although she acknowledges that “it seems so dated to poison a person” still, “watching my skin bruise, my graying face, / the overall weakness of slumping muscles, / I consider my toxic unraveling,” and demands, “send the police, the CIA. Someone must pay / for doing me in.” In “A Version Of,” she addresses that messy mix of experiences and inevitable lacunae:

My life has been

a version of being

as has yours and Barry’s dog life

(privileged but with hard losses).

The bird who hit my plate glass

but never went hungry in this seedberry acre

or thirsty living near a creek

was a version of a bird’s life.

Isn’t it something to think of?

How unique we are not just in feature but in span

not just in luck but in plate glass

and that doesn’t begin to account for

the climate, vicinity, or hunger

of your version.

Morgan finds omens everywhere in these versions: A wading bird stands all day “in my yard, / in my cluttered neighborhood, miles from water, fish, its kind,” and no one “noticed the Great Blue Heron / dying by my Pontiac.” Watching a bridge under construction in the title poem, she remarks, “‘that’s a fine span . . . a very long one— / they didn’t make ’em like that back then.’ Or us / either . . .” But at poem’s end, “Our span is ready.”

In “Black Animals,” her most overtly vatic poem, set in the mountains, she encounters in the same day “a black bull . . . in my fenced yard” and “halfway through my cabin’s opened door / a black snake,” all at a time when the speaker has a date with a friend and must be “down in the valley by sunset” and must drive “in the dark after dinner / back up the mountain.” Rather than wrap up the anecdote as expected by telling us what the speaker finds at the end of her journey, Morgan simply asks, “Can you realize this is the end of my story, and yours?”

While her story and ours may end with unanswered and unanswerable questions, we can still hope that Elizabeth Seydel Morgan will continue to provide us with poems and collections as rich as Spans. ![]()

![]()

“A Version Of” from Spans: New and Selected Poems, 2014 by Elizabeth Seydel Morgan, used by permission of Louisiana State University Press.

Elizabeth Seydel Morgan is the author of five books of poetry published by Louisiana State University Press, most recently, Spans: New and Selected Poems (2014), Without a Philosophy (2007), and On Long Mountain (1998). Her poetry has been published in Poetry, The Southern Review, The Iowa Review, and Blackbird, among others. Morgan was awarded the inaugural Carole Weinstein Prize in Poetry in 2005. She has also received the Emily Clark Balch Award from Virginia Quarterly Review for her fiction, as well as a Theresa Pollack Prize for Excellence in the Arts from Richmond Magazine (2005). Morgan was a 2007 Louis D. Rubin, Jr. Writer-in-Residence at Hollins University. She serves on the board of curators for the Carole Weinstein Prize in Poetry.